Management of Primary Female Urethral Adenocarcinoma: Two Rare Case Reports and Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

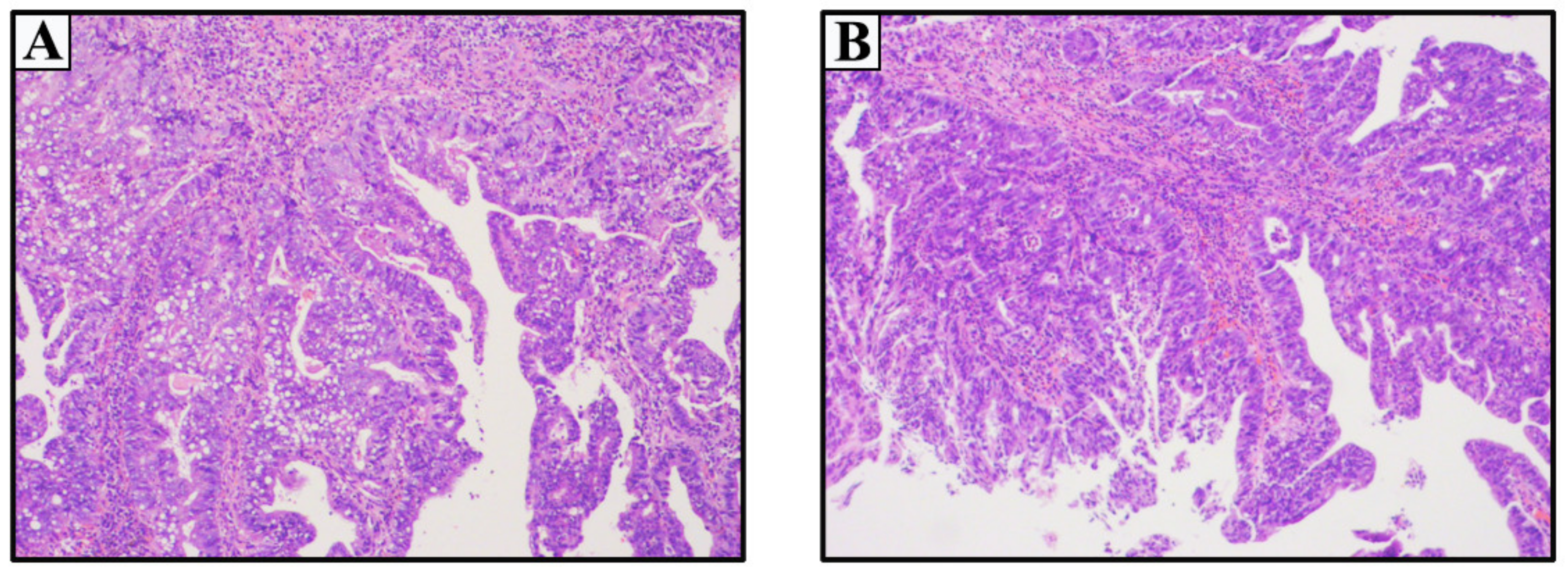

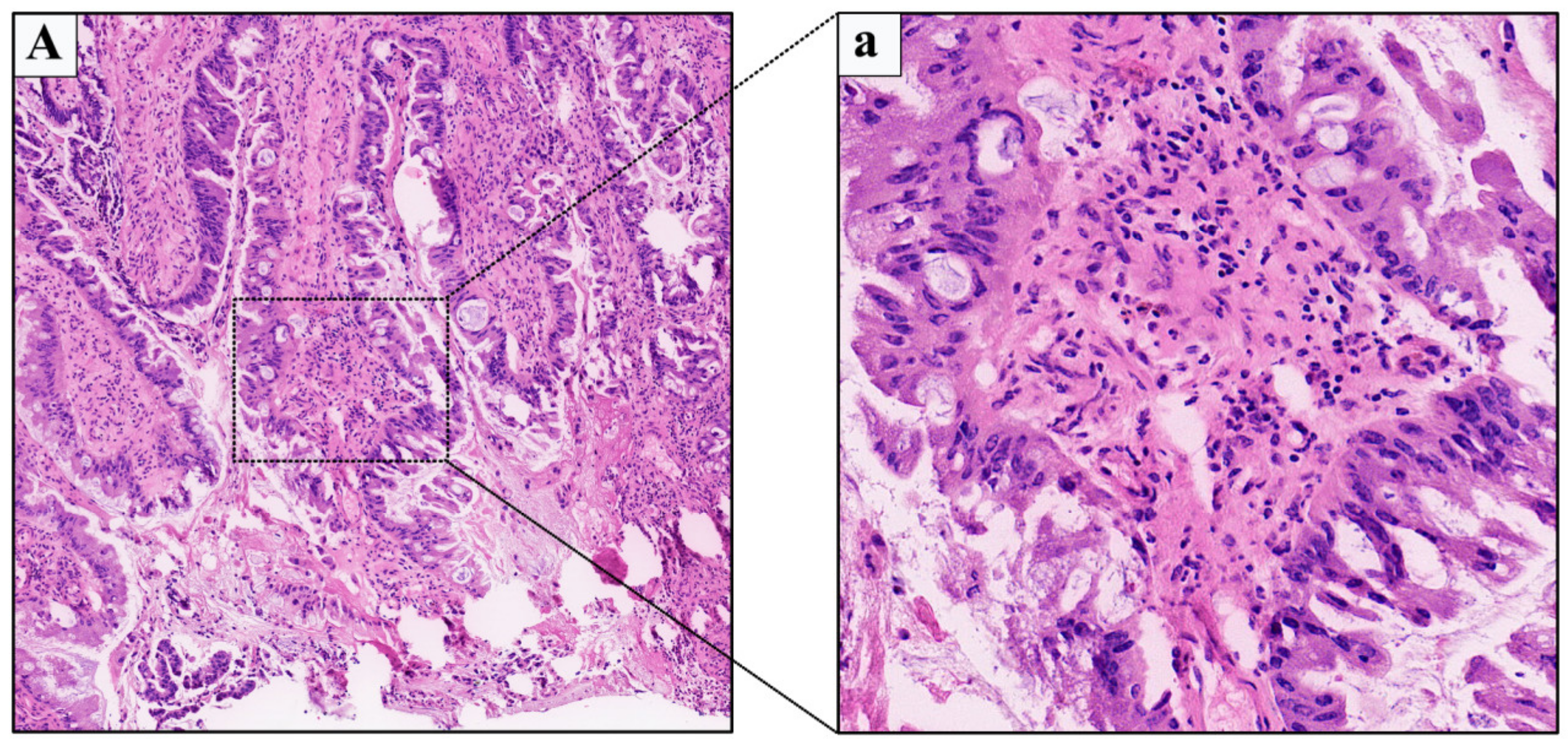

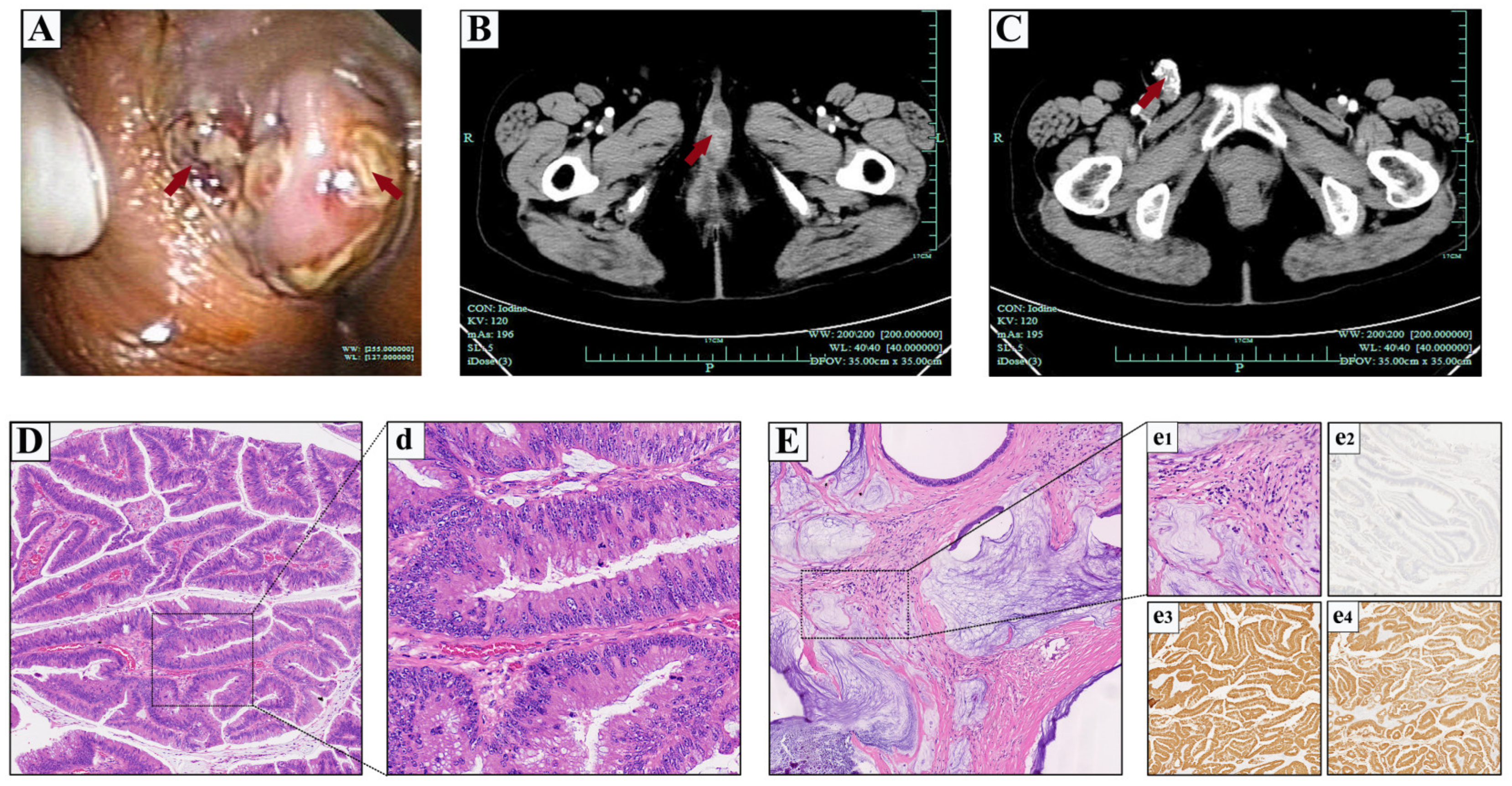

2.1. Case 1

2.2. Case 2

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Srinivas, V.; Khan, S.A. Female urethral cancer--an overview. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 1987, 19, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzaid, I.; Hermieu, J.F.; Dominique, S.; Fernandez, P.; Choudat, L.; Ravery, V. Management of adenocarcinoma of the female urethra: Case report and brief review. Can. J. Urol. 2010, 17, 5404–5407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dodson, M.K.; Cliby, W.A.; Pettavel, P.P.; Keeney, G.L.; Podratz, K.C. Female urethral adenocarcinoma: Evidence for more than one tissue of origin? Gynecol. Oncol. 1995, 59, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, N.; Shiotsu, T.; Ohara, M.; Hirouchi, T.; Mizuno, K.; Miyazaki, E. Female urethral adenocarcinoma with a heterogeneous phenotype. APMIS Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 2006, 114, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y.M.; Ka-Leung Cheng, D.; Nga-Yin Cheung, A.; Yuen-Sheung Ngan, H.; Wong, L.C. Female urethral adenocarcinoma arising from urethritis glandularis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000, 79, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongtippan, A.; Malpica, A.; Levenback, C.; Deavers, M.T.; Silva, E.G. Skene’s gland adenocarcinoma resembling prostatic adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Gynecol. Pathol. 2004, 23, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilcrease, M.Z.; Delgado, R.; Vuitch, F.; Albores-Saavedra, J. Clear cell adenocarcinoma and nephrogenic adenoma of the urethra and urinary bladder: A histopathologic and immunohistochemical comparison. Hum. Pathol. 1998, 29, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheiler, E.L.; Tefilli, M.V.; Tiguert, R.; de Oliveira, J.G.; Pontes, J.E.; Wood, D.P., Jr. Management of primary urethral cancer. Urology 1998, 52, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyavihally, Y.B.; Wuntkal, R.; Bakshi, G.; Uppin, S.; Tongaonkar, H.B. Primary carcinoma of the female urethra: Single center experience of 18 cases. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 35, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gakis, G.; Witjes, J.A.; Compérat, E.; Cowan, N.C.; De Santis, M.; Lebret, T.; Ribal, M.J.; Sherif, A.M. EAU guidelines on primary urethral carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2013, 64, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, C.E.; Hegarty, S.E.; Shen, X.; Mishra, M.V.; Dicker, A.P.; Trabulsi, E.J.; Lallas, C.D.; Gomella, L.G.; Hyslop, T.; Showalter, T.N. Prognostic factors and outcomes after definitive treatment of female urethral cancer: A population-based analysis. Urology 2012, 80, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, L.O.; Billis, A.; Ferreira, F.T.; Ikari, L.Y.; Stellini, R.F.; Ferreira, U. Female urethral carcinoma: Evidences to origin from Skene’s glands. Urol. Oncol. 2011, 29, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, M.A.; Porter, M.P.; Lin, D.W.; Weiss, N.S. Incidence of primary urethral carcinoma in the United States. Urology 2006, 68, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Dasgupta, R.; Vats, A.; Nagpal, K.; Ashrafian, H.; Kaj, B.; Athanasiou, T.; Dasgupta, P.; Khan, M.S. Urethral diverticular carcinoma: An overview of current trends in diagnosis and management. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2010, 42, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Iatropoulou, D.; Hashimoto, S.; Takahashi, S.; Ho, D.H.; Greenwell, T. Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females-a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, 703–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.A.; Rackley, R.R.; Lee, U.; Goldman, H.B.; Vasavada, S.P.; Hansel, D.E. Urethral diverticula in 90 female patients: A study with emphasis on neoplastic alterations. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 2463–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, B.; Chao, D.; Schneider, B.F. Non-surgical treatment of primary female urethral cancer. Rare Tumors 2010, 2, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.B.; Epstein, J.I. Primary carcinoid tumors of the urinary bladder and prostatic urethra: A clinicopathologic study of 6 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, S.E.; Cheng, L.; Osunkoya, A.O. Primary mucinous adenocarcinoma of the female urethra: A contemporary clinicopathologic analysis. Hum. Pathol. 2016, 47, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, A.; Lochhead, A.; Dally, E.; Starra, E.; Lynnhtun, K. PSA-positive urethral adenocarcinoma of female genital tract. Pathology 2019, 51, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.K.; Cliby, W.A.; Keeney, G.L.; Peterson, M.F.; Podratz, K.C. Skene’s gland adenocarcinoma with increased serum level of prostate-specific antigen. Gynecol. Oncol. 1994, 55, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tregnago, A.C.; Epstein, J.I. Skene’s Glands Adenocarcinoma: A Series of 4 Cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 42, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, C.S.; Huang, H.; Melamed, J.; Xu, R.; Roberts, L.; Wieczorek, R.; Pei, Z.; Lee, P. Urethral adenocarcinoma associated with intestinal-type metaplasia, case report and literature review. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karnes, R.J.; Breau, R.H.; Lightner, D.J. Surgery for urethral cancer. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 37, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, A.; Sandler, C.M.; Wasserman, N.F.; LeRoy, A.J.; King, B.F., Jr.; Goldman, S.M. Imaging of urethral disease: A pictorial review. Radiographics 2004, 24 (Suppl. 1), S195–S216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudicella, R.; Davidzon, G.; Vasanawala, S.; Baldari, S.; Iagaru, A. (18)F-FDG PET/MR Refines Evaluation in Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Urethral Adenocarcinoma. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 53, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Gu, J.J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.L. Ultrasonographic Imaging Features of Female Urethral and Peri-urethral Masses: A Retrospective Study of 95 Patients. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2020, 46, 1896–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, O.; Adolfsson, J.; Rossi, S.; Verne, J.; Gatta, G.; Maffezzini, M.; Franks, K.N. Incidence and survival of rare urogenital cancers in Europe. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyton, C.C.; Azizi, M.; Chipollini, J.; Ercole, C.; Fishman, M.; Gilbert, S.M.; Juwono, T.; Lockhart, J.; Poch, M.; Pow-Sang, J.M.; et al. Survival Outcomes Associated With Female Primary Urethral Carcinoma: Review of a Single Institutional Experience. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2018, 16, e1003–e1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Yu, J.; Lee, J.L.; Kim, Y.S.; Hong, B. Clinical features and oncological outcomes of primary female urethral cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 125, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, D.B.; Handorf, E.; Ristau, B.T.; Geynisman, D.M.; Simhan, J.; Kutikov, A.; Greenberg, R.E.; Viterbo, R.; Chen, D.Y.T.; Uzzo, R.G.; et al. Contemporary practice patterns and survival outcomes for locally advanced urethral malignancies: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Urol. Oncol. 2017, 35, 670.e15–670.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, T.Y.; Chen, T.W.; Patel, A.J.; Vincent, J.N.; Ha, C.S. Treatment and Outcomes of Primary Urethra Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 41, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksic, I.; Rais-Bahrami, S.; Daugherty, M.; Agarwal, P.K.; Vourganti, S.; Bratslavsky, G. Primary urethral carcinoma: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data analysis identifying predictors of cancer-specific survival. Urol. Ann. 2018, 10, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, R.; Vertosick, E.A.; Sarcona, J.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Benfante, N.E.; Donahue, T.F.; Herr, H.W.; Donat, S.M.; Bochner, B.H.; Dalbagni, G.; et al. Primary urethral cancer: Treatment patterns and associated outcomes. BJU Int. 2020, 126, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimarco, D.S.; Dimarco, C.S.; Zincke, H.; Webb, M.J.; Bass, S.E.; Slezak, J.M.; Lightner, D.J. Surgical treatment for local control of female urethral carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 2004, 22, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMarco, D.S.; DiMarco, C.S.; Zincke, H.; Webb, M.J.; Keeney, G.L.; Bass, S.; Lightner, D.J. Outcome of surgical treatment for primary malignant melanoma of the female urethra. J. Urol. 2004, 171, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, A.S.; Zagars, G.K.; Delclos, L. Primary carcinoma of the female urethra. Results of radiation therapy. Cancer 1993, 71, 3102–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Sugino, Y.; Owa, S.; Kitano, G.; Sasaki, T.; Kato, M.; Masui, S.; Nishikawa, K.; Yoshio, Y.; Kanda, H.; et al. Neoajuvant Chemotherapy with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Plus S-1 for Primary Female Urethral Adenocarcinoma. Hinyokika kiyo. Acta Urol. Jpn. 2020, 66, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayyani, F.; Pettaway, C.A.; Kamat, A.M.; Munsell, M.F.; Sircar, K.; Pagliaro, L.C. Retrospective analysis of survival outcomes and the role of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with urethral carcinomas referred to medical oncologists. Urol. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hara, I.; Hikosaka, S.; Eto, H.; Miyake, H.; Yamada, Y.; Soejima, T.; Sugimura, K.; Kamidono, S. Successful treatment for squamous cell carcinoma of the female urethra with combined radio- and chemotherapy. Int. J. Urol. Off. J. Jpn. Urol. Assoc. 2004, 11, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.P.; Lin, S.J.; Fu, T.Y.; Yu, M.S. Locally advanced female urethral adenocarcinoma of enteric origin: The role of adjuvant chemoradiation and brief review. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2011, 27, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Son, C.H.; Liauw, S.L.; Hasan, Y.; Solanki, A.A. Optimizing the Role of Surgery and Radiation Therapy in Urethral Cancer Based on Histology and Disease Extent. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 102, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuzillet, Y.; Soulie, M.; Larre, S.; Roupret, M.; Defortescu, G.; Murez, T.; Pignot, G.; Descazeaud, A.; Patard, J.J.; Bigot, P.; et al. Positive surgical margins and their locations in specimens are adverse prognosis features after radical cystectomy in non-metastatic carcinoma invading bladder muscle: Results from a nationwide case-control study. BJU Int. 2013, 111, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claps, F.; van de Kamp, M.W.; Mayr, R.; Bostrom, P.J.; Boormans, J.L.; Eckstein, M.; Mertens, L.S.; Boevé, E.R.; Neuzillet, Y.; Burger, M.; et al. Risk factors associated with positive surgical margins’ location at radical cystectomy and their impact on bladder cancer survival. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 4363–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picozzi, S.; Ricci, C.; Gaeta, M.; Ratti, D.; Macchi, A.; Casellato, S.; Bozzini, G.; Carmignani, L. Upper urinary tract recurrence following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: A meta-analysis on 13,185 patients. J. Urol. 2012, 188, 2046–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, L.S.; Claps, F.; Mayr, R.; Bostrom, P.J.; Shariat, S.F.; Zwarthoff, E.C.; Boormans, J.L.; Abas, C.; van Leenders, G.; Götz, S.; et al. Prognostic markers in invasive bladder cancer: FGFR3 mutation status versus P53 and KI-67 expression: A multi-center, multi-laboratory analysis in 1058 radical cystectomy patients. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 40, 110.e1–110.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claps, F.; Mir, M.C.; Zargar, H. Molecular markers of systemic therapy response in urothelial carcinoma. Asian J. Urol. 2021, 8, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.C.; Campi, R.; Loriot, Y.; Puente, J.; Giannarini, G.; Necchi, A.; Rouprêt, M. Adjuvant Systemic Therapy for High-risk Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer After Radical Cystectomy: Current Options and Future Opportunities. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, M.; Maybodi, M.N.; Abolhasani, M. Differential diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma in situ from non-neoplastic urothelia: Analysis of CK20, CD44, P53 and Ki67. Med. J. Islamic Repub. Iran 2016, 30, 400. [Google Scholar]

- Stojnev, S.; Ristic-Petrovic, A.; Velickovic, L.J.; Krstic, M.; Bogdanovic, D.; Khanh do, T.; Ristic, A.; Conic, I.; Stefanovic, V. Prognostic significance of mucin expression in urothelial bladder cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 4945–4958. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi, P.J.; Wang, J.; Delprado, W.; Perkins, A.C.; Allen, B.J.; Russell, P.J.; Li, Y. MUC1, MUC2, MUC4, MUC5AC and MUC6 expression in the progression of prostate cancer. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2005, 22, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.M.; Wahbbah, M.A.; Selem, M.; Abdou, A.G.; Sultan, S.M. Correlation between immunohistochemical expression of Ki-67and P63 and aggressiveness of urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 2021, 42, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Akhir, M.K.A.; Hussin, H.; Veerakumarasivam, A.; Choy, C.S.; Abdullah, M.A.; Abd Ghani, F. Immunohistochemical expression of NANOG in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Malays. J. Pathol. 2017, 39, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, K.H.; Siddiqui, M.T.; Cohen, C. GATA3 immunohistochemical expression in invasive urothelial carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 432.e9–432.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakis, G.; Bruins, H.M.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; van der Heijden, A.G.; Hernández, V.; Espinós, E.E.L.; Lorch, A.; Neuzillet, Y.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Primary Urethral Carcinoma-2020 Update. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 3, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, J.; Zhu, T.; Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Fu, G.; Jin, B. Management of Primary Female Urethral Adenocarcinoma: Two Rare Case Reports and Literature Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010109

Tian J, Zhu T, Xu Z, Chen X, Wu Y, Fu G, Jin B. Management of Primary Female Urethral Adenocarcinoma: Two Rare Case Reports and Literature Review. Medicina. 2023; 59(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Junjie, Ting Zhu, Zhijie Xu, Xiaoyi Chen, Yunfei Wu, Guanghou Fu, and Baiye Jin. 2023. "Management of Primary Female Urethral Adenocarcinoma: Two Rare Case Reports and Literature Review" Medicina 59, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010109

APA StyleTian, J., Zhu, T., Xu, Z., Chen, X., Wu, Y., Fu, G., & Jin, B. (2023). Management of Primary Female Urethral Adenocarcinoma: Two Rare Case Reports and Literature Review. Medicina, 59(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010109