Incidental Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Liver Transplantation: Clinicopathologic Features and Prognosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Features

3.2. Histopathological Features of Incidental HCC and Preop Diagnosed HCC

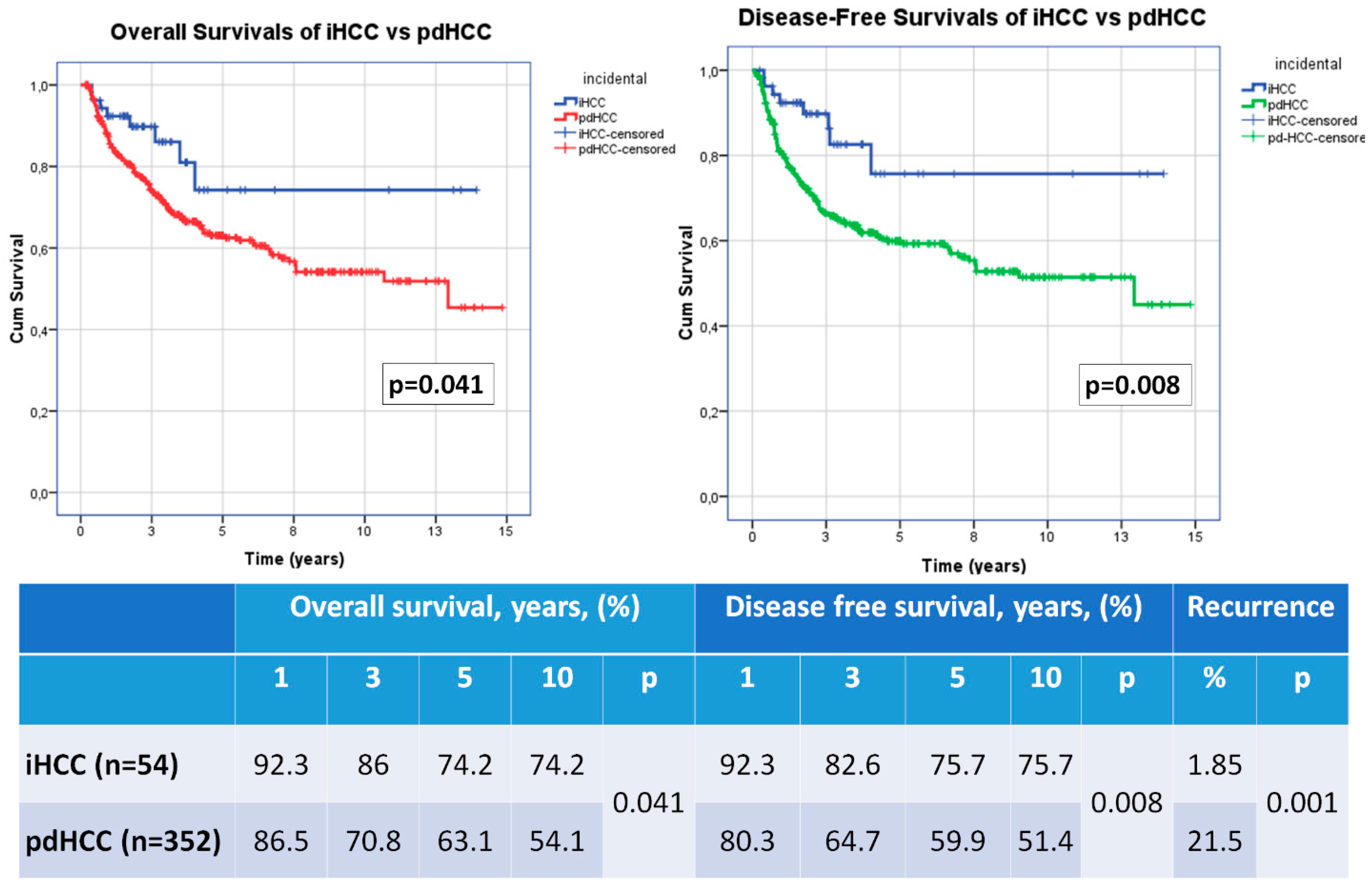

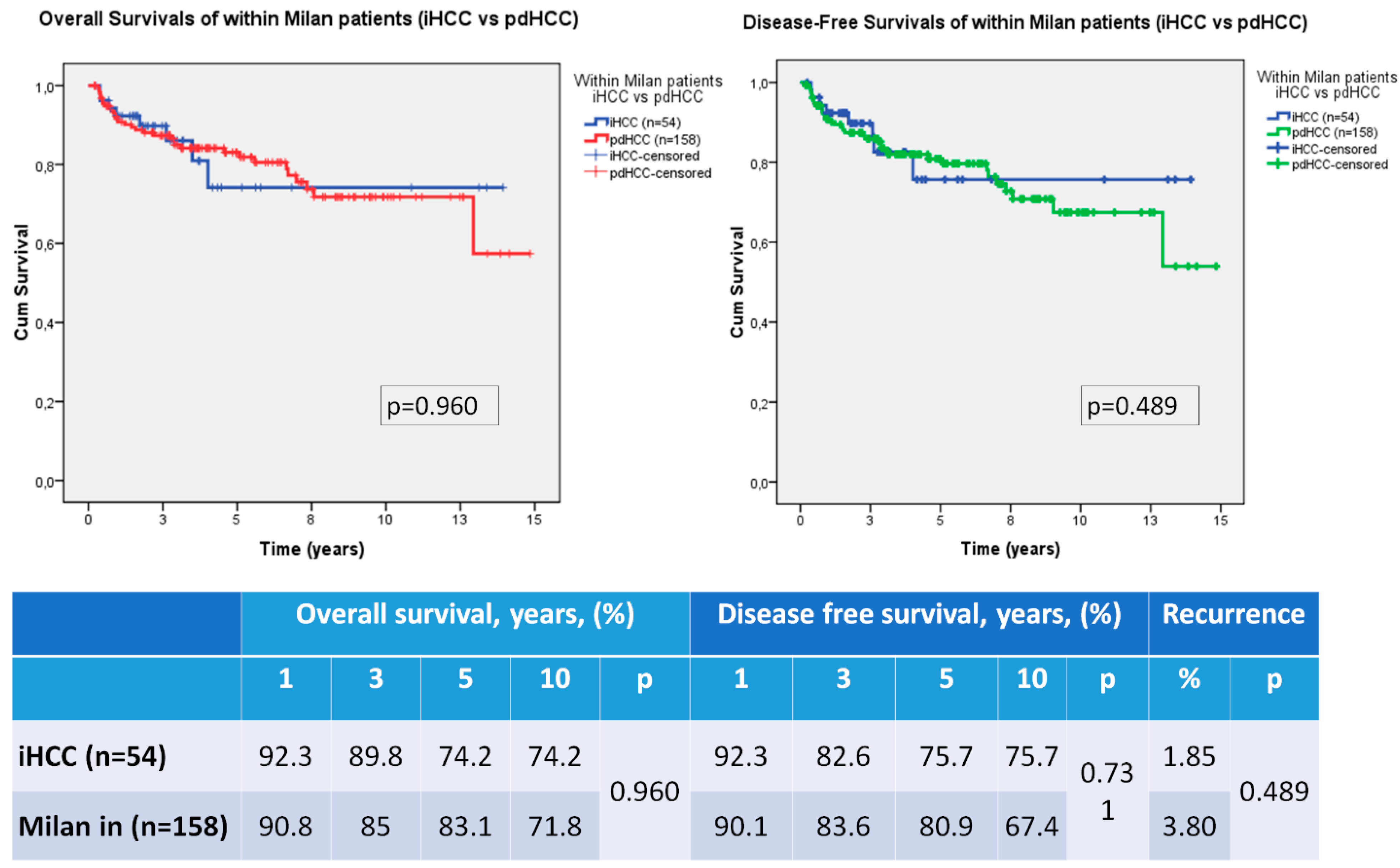

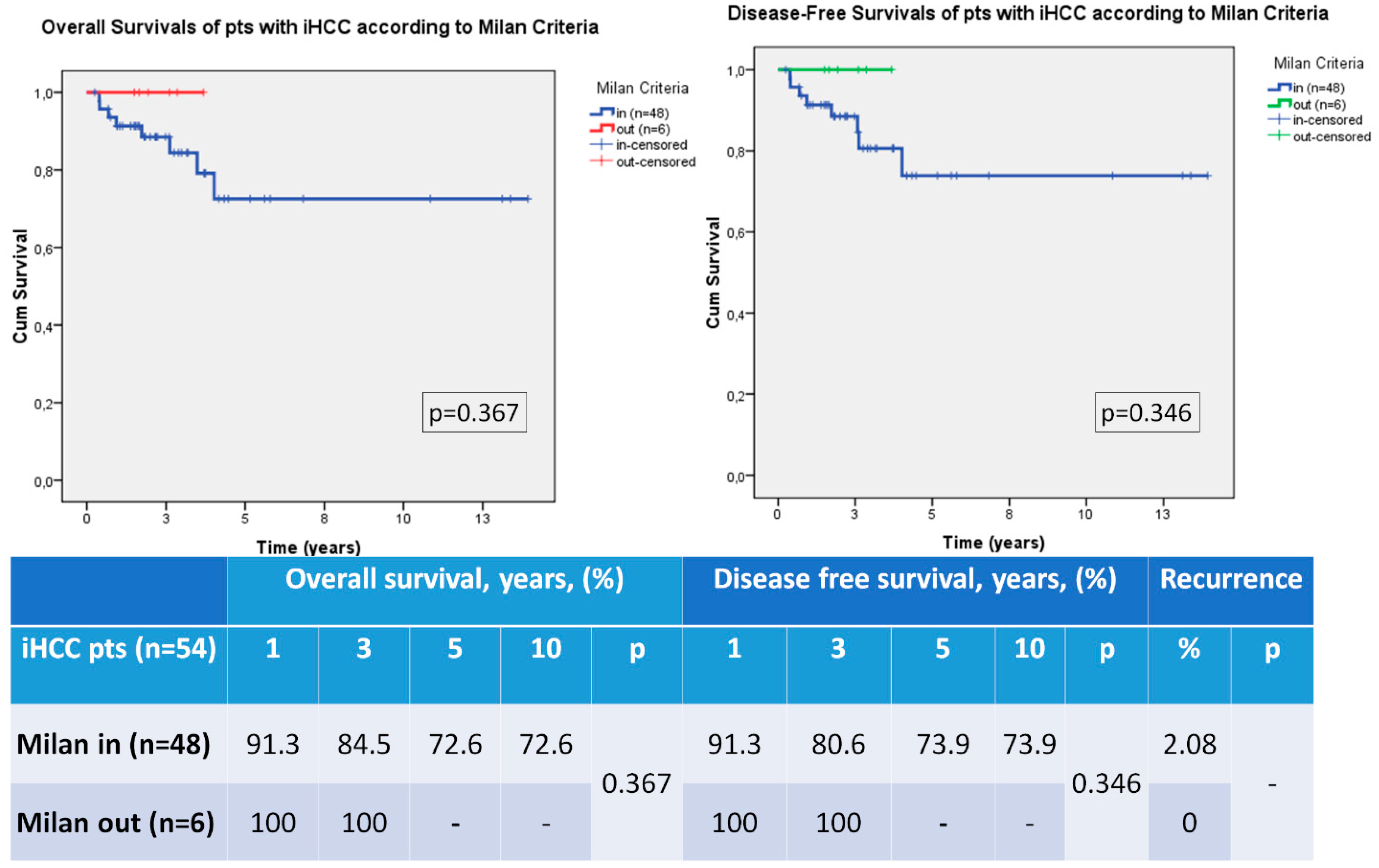

3.3. Recurrence, Overall Survival and Disease Free Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Adam, R.; Karam, V.; Delvart, V.; O’Grady, J.; Mirza, D.; Klempnauer, J.; Castaing, D.; Neuhaus, P.; Jamieson, N.; Salizzoni, M.; et al. Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantation in Europe. A report from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR). J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaferro, V.; Regalia, E.; Doci, R.; Andreola, S.; Pulvirenti, A.; Bozzetti, F.; Montalto, F.; Ammatuna, M.; Morabito, A.; Gennari, L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaferro, V.; Llovet, J.M.; Miceli, R.; Bhoori, S.; Schiavo, M.; Mariani, L.; Camerini, T.; Roayaie, S.; Schwartz, M.E.; Grazi, G.L.; et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: A retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Misas, M.; Rodriguez-Peralvarez, M.; De la Mata, M. Strategies to improve outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving a liver transplantation. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, G.C.; Malago, M.; Molmenti, E.P.; Nadalin, S.; Radtke, A.; Brokalaki, E.I.; Lang, H.; Frilling, A.; Baba, H.A.; Neuhäuser, M.; et al. Liver transplantation and incidentally found hepatocellular carcinoma in liver explants: Need for a new definition? Transplantation 2006, 81, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, E.; Pelletier, S.; Kumer, S.; Abouljoud, M.; Divine, G.; Moonka, D. Incidental hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: Population characteristics and outcomes. Transplant Proc. 2009, 41, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkerikova, R.; Frankova, S.; Sperl, J.; Oliverius, M.; Kieslichova, E.; Filipova, H.; Kautznerova, D.; Honsova, E.; Trunecka, P.; Spicak, J. Incidental hepatocellular carcinoma: Risk factors and long-term outcome after liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2014, 46, 1426–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M.M.; Algarni, A.; Aly, M.A.; Gunson, B.K.; Mergental, H.; Isaac, J.; Muiesan, P.; Mirza, D.; Perera, M.T.P.R.; Bramhall, S.R. Tumor Characteristics and Long-Term Outcome of Incidental Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Orthotopic Liver Transplant. Exp. Clin. Transpl. 2015, 13, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelfattah, M.R.; Abaalkhail, F.; Al-Manea, H. Misdiagnosed or Incidentally Detected Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Explanted Livers: Lessons Learned. Ann. Transpl. 2015, 20, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moghazy, W.; Kashkoush, S.; Meeberg, G.; Kneteman, N. Incidence, characteristics and prognosis of incidentally discovered hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. J. Transp. Secur. 2016, 2016, 1916387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, P.; Rodriguez-Peralvarez, M.; Guerrero, L.; González, V.; Sánchez, R.; Centeno, M.; Poyato, A.; Briceño, J.; Sánchez-Frías, M.; Montero, J.L.; et al. Incidental hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: Prevalence, histopathological features and prognostic impact. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.S.; Knechtle, S.J.; Heisey, D.M.; Hermina, M.; Armbrust, M.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Musat, A.I.; Kalayoglu, M. Analysis of tumor characteristics and survival in liver transplant recipients with incidentally diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2001, 5, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinero, F.; Mendizabal, M.; Casciato, P.; Galdame, O.; Quiros, R.; Bandi, J.; Mullen, E.; Andriani, O.; de Santibañes, E.; Podestá, L.G.; et al. Is recurrence rate of incidental hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation similar to previously known HCC? towards a predictive recurrence score. Ann. Hepatol. 2014, 13, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, A.K.; Wong, J.; Rao, A.R.; Ng, S.S.; Chan, F.K.; Chan, H.L.; Chan, C.; Mi, R.; Lau, W. High incidence of incidental hepatocellular carcinoma exists among hepatitic explanted livers. Transplant Proc. 2003, 35, 350–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaleno, J.; Alves, R.; Silva, N.; Calretas, S.; Tome, L.; Ferrao, J.; Barros, A.; Diogo, D.; Cipriano, A.; Furtado, E.; et al. Incidentally discovered hepatocellular carcinoma in explanted liver: Clinical, histopathologic features and outcome. Transpl. Proc. 2015, 47, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajakannu, M.; Vij, M.; Shaikh, T.M.A.; Rammohan, A.; Reddy, M.S.; Rela, M. Prognostic impact of incidentally detected hepatocellular carcinoma in explanted livers after living donor liver transplantation. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 40, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, S.; Mittler, J.; Pascher, A.; Schumacher, G.; Theruvath, T.; Benckert, C.; Rudolph, B.; Neuhaus, P. Living donor liver transplantation of the right lobe for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis in a European center. Liver Transpl. 2007, 13, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirabe, K.; Taketomi, A.; Morita, K.; Soejima, Y.; Uchiyama, H.; Kayashima, H.; Ninomiya, M.; Toshima, T.; Maehara, Y. Comparative evaluation of expanded criteria for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria undergoing living-related donor liver transplantation. Clin. Transpl. 2011, 25, E491–E498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapisochin, G.; Goldaracena, N.; Laurence, J.M.; Dib, M.; Barbas, A.; Ghanekar, A.; Cleary, S.P.; Lilly, L.; Cattral, M.S.; Marquez, M.; et al. The extended Toronto criteria for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective validation study. Hepatology 2016, 64, 2077–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, V.; Akbulut, S.; Otan, E.; Ersan, V.; Karakas, S.; Sahin, T.T.; Carr, B.I.; Baskiran, A.; Samdanci, E.; Bag, H.G.; et al. Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Malatya Experience and Proposals for Expanded Criteria. J. Gastrointest Cancer 2020, 51, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, V.; Carr, B.I.; Bag, H.G.; Ersan, V.; Usta, S.; Koc, C.; Gonultas, F.; Sarici, B.K.; Karakas, S.; Kutluturk, K.; et al. Liver transplant for large hepatocellular carcinoma in Malatya: The role of gamma glutamyl transferase and alpha-fetoprotein, a retrospective cohort study. World J. Gastrointest Surg. 2020, 12, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables (n, %) | pdHCC (n = 352) | iHCC (n = 54) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [Median (min.-max.)] | 56 (4-72) | 53.5 (2-72) | 0.047 |

Gender

| 303 (86.1) 49 (13.9) | 46 (85.2) 8 (14.8) | 1.000 |

| BMI [Median (min.-max.)] | 25.7 (16.3-46.9) | 26.9 (16.4-41) | 0.474 |

Underlying liver disease

| 292 (83) a 40 (11.4) a 5 (1.4) a 4 (1.1) 4 (1.1) 2 (0.6) 5 (1.4) | 32 (59.3) b 12 (22.2) b 4 (7.4) b 2 (3.7) 2 (3.7) 1 (1.9) 1(1.9) | 0.012 |

| MELD/ PELD score [Median (min.–max.)] | 12 (6-41) | 16.5 (9-31) | <0.001 |

Child–Pugh Score

| 133 (37.8) a 149 (42.3) 70 (19.9) a | 3 (5.6) b 27 (50.0) 24 (44.4) b | <0.001 |

| PreTx AFP (ng/mL), [Median (min.–max.)] | 15.3 (0.2-20,179) | 4.45 (0.4-1001) | <0.001 |

| GGT (IU/mL), [Median (min.–max.)] | 74 (11-1396) | 49.5 (13-349) | 0.001 |

| Variables (n, %) | pdHCC (n = 352) | iHCC (n = 54) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

Number of nodules

| 166 (47.2) 186 (52.8) | 36 (66.7) 18 (33.3) | 0.012 |

| MTD (cm) [Median (min.–max.)] | 3.5 (0.1-24) | 1 (0.1-2.5) | <0.001 |

Tm differentiation

| 127 (36.1) a 161 (45.7) a 64 (18.2) a | 43 (79.6) b 10 (18.5) b 1 (1.9) b | <0.001 |

Vascular invasion

| 48 (13.6) a 135 (38.4) a 169 (48.0) a | 0 (0) b 4 (7.4) b 50 (92.6) b | <0.001 |

Milan criteria

| 158 (44.9) 194 (55.1) | 48 (88.9) 6 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Locoregional therapy pre-LT | 71 (20.2) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ozdemir, F.; Ince, V.; Usta, S.; Carr, B.I.; Bag, H.G.; Akatli, A.N.; Kahraman, A.S.; Yilmaz, S. Incidental Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Liver Transplantation: Clinicopathologic Features and Prognosis. Medicina 2023, 59, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010030

Ozdemir F, Ince V, Usta S, Carr BI, Bag HG, Akatli AN, Kahraman AS, Yilmaz S. Incidental Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Liver Transplantation: Clinicopathologic Features and Prognosis. Medicina. 2023; 59(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzdemir, Fatih, Volkan Ince, Sertac Usta, Brian I. Carr, Harika G. Bag, Ayse Nur Akatli, Aysegul Sagir Kahraman, and Sezai Yilmaz. 2023. "Incidental Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Liver Transplantation: Clinicopathologic Features and Prognosis" Medicina 59, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010030

APA StyleOzdemir, F., Ince, V., Usta, S., Carr, B. I., Bag, H. G., Akatli, A. N., Kahraman, A. S., & Yilmaz, S. (2023). Incidental Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Liver Transplantation: Clinicopathologic Features and Prognosis. Medicina, 59(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59010030