Acute Coronary Syndrome Presenting during On- and Off-Hours: Is There a Difference in a Tertiary Cardiovascular Center?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diletti, R.; Dekker, W.K.D.; Bennett, J.; Schotborgh, C.E.; van der Schaaf, R.; Sabaté, M.; Moreno, R.; Ameloot, K.; van Bommel, R.; Forlani, D.; et al. Immediate versus staged complete revascularisation in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and multivessel coronary disease (BIOVASC): A prospective, open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Lopes, R.D.; Harrington, R.A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Review. JAMA 2022, 327, 662–675, Erratum in JAMA 2022, 327, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collet, J.-P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Ye, X.; Liu, C.; Xie, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, B.; Wang, B. Outcomes of off- and on-hours admission in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: A retrospective observational cohort study. Medicine 2016, 95, e4093, Erratum in Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubeddu, R.J.; Palacios, I.F.; Blankenship, J.C.; Horvath, S.A.; Xu, K.; Kovacic, J.C.; Dangas, G.D.; Witzenbichler, B.; Guagliumi, G.; Kornowski, R.; et al. Outcome of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention during on- versus off-hours (a harmonizing outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction [HORIZONS-AMI] trial substudy). Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarek, T.; Dziewierz, A.; Plens, K.; Rakowski, T.; Jaroszyńska, A.; Bartuś, S.; Siudak, Z. Percutaneous coronary intervention during on- and off-hours in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Hell. J. Cardiol. 2021, 62, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, S.P.; Oemrawsingh, R.M.; Lenzen, M.J.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Schultz, C.; Akkerhuis, K.M.; Van Leeuwen, M.A.; Zijlstra, F.; Van Domburg, R.T.; Serruys, P.W.; et al. Primary PCI during off-hours is not related to increased mortality. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2012, 1, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfors, B.; Dworeck, C.; Angerås, O.; Haraldsson, I.; Petursson, P.; Odenstedt, J.; Ioanes, D.; Völz, S.; Hiller, M.; Fransson, P.; et al. Prognosis is similar for patients who undergo primary PCI during regular-hours and off-hours: A report from SCAAR*. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 91, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marume, K.; Nagatomo, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Kaichi, R.; Mori, T.; Komaki, S.; Ishii, M.; Kusaka, H.; Toida, R.; Kurogi, K.; et al. Prognostic impact of the presence of on-duty cardiologist on patients with acute myocardial infarction admitted during off-hours. J. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enezate, T.H.; Omran, J.; Al-Dadah, A.S.; Alpert, M.; Mahmud, E.; Patel, M.; Aronow, H.D.; Bhatt, D.L. Comparison of Outcomes of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated by Percutaneous Coronary Intervention during Off-Hours Versus On-Hours. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, 1742–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, K.; Negrone, A.; Redfern, J.; Atkins, E.; Chow, C.; Kilian, J.; Rajaratnam, R.; Brieger, D. Gender Difference in Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Outcomes Following the Survival of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Heart Lung Circ. 2021, 30, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagidipati, N.J.; Huffman, M.D.; Jeemon, P.; Gupta, R.; Negi, P.; Jaison, T.M.; Sharma, S.; Sinha, N.; Mohanan, P.; Muralidhara, B.G.; et al. Association between gender, process of care measures, and outcomes in ACS in india: Results from the detection and management of coronary heart disease (DEMAT) registry. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossello, X.; Ferreira, J.P.; Caimari, F.; Lamiral, Z.; Sharma, A.; Mehta, C.; Bakris, G.; Cannon, C.P.; White, W.B.; Zannad, F. Influence of sex, age and race on coronary and heart failure events in patients with diabetes and post-acute coronary syndrome. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2021, 110, 1612–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, P.; Savu, A.; Bainey, K.R.; Kaul, P.; Welsh, R.C. Long-term risk of death and recurrent cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndromes. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, R.; Johnson, M.; Kravitz, K.; Huded, C.; Rajeswaran, J.; Anabila, M.; Blackstone, E.; Menon, V.; Lincoff, A.M.; Kapadia, S.; et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Early Recurrent Myocardial Infarction after Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y. Impact of off-hour admission on the MACEs of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2023, 45, 2186317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Suryapranata, H.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Hof, A.W.V.; Hoorntje, J.C.; Gosselink, A.M.; Dambrink, J.-H.E.; Zijlstra, F.; de Boer, M.-J. Circadian variation in myocardial perfusion and mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Am. Heart J. 2005, 150, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.K.; Wells, G.; So, D.Y.; Chong, A.-Y.; Dick, A.; Froeschl, M.; Glover, C.; Hibbert, B.; Labinaz, M.; Russo, J.; et al. Off-Hours Presentation, Door-to-Balloon Time, and Clinical Outcomes in Patients Referred for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 35, E185–E193. [Google Scholar]

- Magid, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Herrin, J.; McNamara, R.L.; Bradley, E.H.; Curtis, J.P.; Pollack, C.V., Jr.; French, W.J.; Blaney, M.E.; Krumholz, H.M. Relationship between time of day, day of week, timeliness of reperfusion, and in-hospital mortality for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA 2005, 294, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, B.; Behrens, S.; Graf-Bothe, C.; Kuckuck, H.; Roehnisch, J.-U.; Schoeller, R.G.; Schuehlen, H.; Theres, H.P. Time of admission, quality of PCI care, and outcome of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2010, 99, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorita, A.; Ahmed, A.; Starr, S.R.; Thompson, K.M.; Reed, D.A.; Prokop, L.; Shah, N.D.; Murad, M.H.; Ting, H.H. Off-hour presentation and outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014, 348, f7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, J.; Buerhaus, P.; Pankratz, V.S.; Leibson, C.L.; Stevens, S.R.; Harris, M. Nurse staffing and inpatient hospital mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallazzi, R.; Marik, P.E.; Hirani, A.; Pachinburavan, M.; Vasu, T.S.; Leiby, B.E. Association between time of admission to the icu and mortality: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest 2010, 138, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolly, S.S.; Yusuf, S.; Cairns, J.; Niemelä, K.; Xavier, D.; Widimsky, P.; Budaj, A.; Niemelä, M.; Valentin, V.; Lewis, B.S.; et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): A randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valgimigli, M.; Gagnor, A.; Calabró, P.; Frigoli, E.; Leonardi, S.; Zaro, T.; Rubartelli, P.; Briguori, C.; Andò, G.; Repetto, A.; et al. Radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing invasive management: A randomised multicentre trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romagnoli, E.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Sciahbasi, A.; Politi, L.; Rigattieri, S.; Pendenza, G.; Summaria, F.; Patrizi, R.; Borghi, A.; Di Russo, C.; et al. Radial versus femoral randomized investigation in st-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: The rifle-steacs (radial versus femoral randomized investigation in ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 60, 2481–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Brennan, A.; Duffy, S.J.; Andrianopoulos, N.; Chan, W.; Walton, A.; Noaman, S.; Shaw, J.A.; Ajani, A.; Clark, D.J.; et al. The Impact of Out-of-Hours Presentation on Clinical Outcomes in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Heart Lung Circ. 2020, 29, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H.W.; Yan, M.; Feng, X.Y.; Guang, X.; Gang, W. Influencing factors of developing in-stent restenosis within 2 years after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with coronary heart disease. Guangxi Med. J. 2019, 41, 2451–2454. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, K.; Bian, Y.J.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Y.T. Relevant factors of in-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents. J. Pract. Med. 2020, 36, 1946–1951. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, C.B.; Goldberg, R.J.; Dabbous, O.; Pieper, K.S.; Eagle, K.A.; Cannon, C.P.; Van de Werf, F.; Avezum, A.; Goodman, S.G.; Flather, M.D.; et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 2345–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi, G.; Bellandi, B.; Tarantini, G.; Scudiero, F.; Valenti, R.; Marcucci, R.; Migliorini, A.; Marchionni, N.; Gori, A.M.; Zocchi, C.; et al. Clinical events beyond one year after an acute coronary syndrome: Insights from the RECLOSE 2-ACS study. Eurointervention 2017, 12, 2018–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Bae, D.-H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, D.I.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Bae, J.-W.; Kim, D.-W.; Cho, M.-C.; Hwang, J.Y.; et al. Impact of multivessel versus single-vessel disease on the association between low diastolic blood pressure and mortality after acute myocardial infarction with revascularization. Cardiol. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, N.; Schulman-Marcus, J.; Torosoff, M. Coronary anatomy and comorbidities impact on elective PCI outcomes in left main and multivessel coronary artery disease. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 98, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | ON n = 848 | OFF n = 1025 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 ± 11 | 61 ± 10 | 0.241 |

| Males n (%) | 475 (56) | 635 (62) | 0.011 |

| Heredity n (%) | 296 (35) | 379 (37) | 0.266 |

| Hypertension n (%) | 644 (76) | 738 (72) | 0.064 |

| Diabetes mellitus n (%) | 203 (24) | 215 (21) | 0.087 |

| Dyslipidemia n (%) | 390 (46) | 348 (34) | <0.001 |

| PAD n (%) | 43 (5) | 45 (4) | 0.255 |

| Smoking n (%) | 356 (42) | 474 (46) | 0.167 |

| Previous MI n (%) | 250 (30) | 148 (14) | <0.001 |

| Previous CVA n (%) | 41 (5) | 75 (7) | 0.033 |

| Previous PCI n (%) | 128 (15) | 128 (12) | 0.124 |

| Previous CABG n (%) | 40 (4) | 38 (4) | 0.451 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3 ± 6.9 | 28.5 ± 7.4 | 0.554 |

| LVEF (%) | 38.6 ± 11.3 | 37.8 ± 15.1 | 0.568 |

| Variable | ON n = 848 | OFF n = 1025 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable angina (%) | 99 (12) | 18 (2) | <0.001 |

| STEMI n (%) | 585 (69) | 952 (93) | <0.001 |

| NSTEMI n (%) | 164 (19) | 55 (5) | <0.001 |

| CABG during hosp. n (%) | 7 (0.8) | 5 (0.5) | 0.263 |

| No treatment n (%) | 127 (15) | 138 (13) | 0.187 |

| Days in hospital (days) | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 3.6 ± 4.0 | 0.056 |

| Maximum hs troponin (ng) | 41,789 ± 84,560 | 58,356 ± 62,079 | 0.050 |

| Death during hosp. n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 14 (1.4) | 0.071 |

| Variable | ON n = 848 | OFF n = 1025 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No significant disease n (%) | 174 (20) | 96 (9) | <0.001 |

| Single vessel disease n (%) | 363 (43) | 536 (52) | <0.001 |

| MVD n (%) | 485(57) | 489(48) | 0.006 |

| * Vessels treated | |||

| LAD n (%) | 327 (38) | 475(46) | 0.001 |

| Cx n (%) | 228 (27) | 297 (29) | 0.256 |

| RCA n (%) | 266 (31) | 538 (52) | <0.001 |

| SVG n (%) | 21 (2) | 19 (2) | 0.506 |

| Radial access n (%) | 692 (82) | 883 (86) | 0.004 |

| Multivessel PCI n (%) | 187 (22) | 171 (16) | 0.002 |

| LM PCI n (%) (ng) | 37 (4) | 35 (3) | 0.203 |

| Bifurcation PCI n (%) | 110 (13) | 124 (12) | 0.409 |

| More than one stent n (%) | 341 (41) | 352 (37) | 0.089 |

| Stent diameter < 3.0 mm n (%) | 249 (29) | 276 (27) | 0.331 |

| Variable | ON n = 848 | OFF n = 1025 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

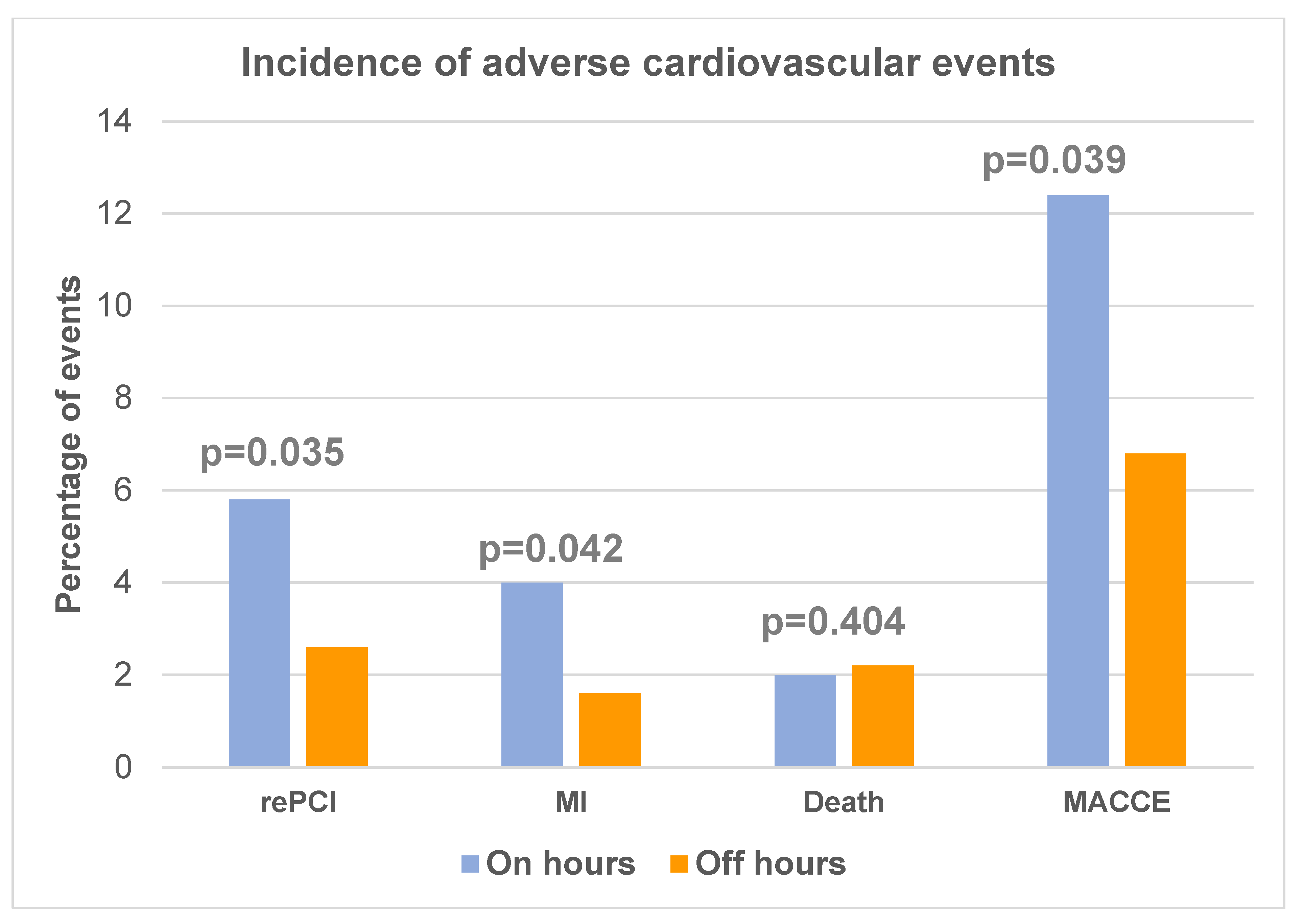

| Death n (%) | 17 (2.0) | 26 (2.54) | 0.404 |

| Myocardial infarction n (%) | 34 (4.0) | 17 (1.6) | 0.042 |

| CVA n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | -------- |

| Repeated PCI n (%) | 49 (5.8) | 27 (2.6) | 0.035 |

| CABG n (%) | 5 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 0.524 |

| MACCE n (%) | 105 (12.4) | 70 (6.8) | 0.039 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CI] | p-Value | HR [95% CI] | p-Value | |

| Age | 1.025 [1.004–1.048] | 0.021 | 1.024 [1.283–3.296] | 0.035 |

| Male sex | 1.310 [0.820–2.090] | 0.258 | - - - | - - - |

| Diabetes | 1.375 [0.792–2.386] | 0.258 | - - - | - - - |

| LVEF | 0.994 [0.971–1.018] | 0.626 | - - - | - - - |

| STEMI | 0.729 [0.405–1.312] | 0.292 | - - - | - - - |

| Multivessel disease | 2.141 [1.339–3.423] | 0.001 | 2.056 [1.283–3.296] | 0.003 |

| On hours admission | 1.755 [0.994–3.099] | 0.052 | 1.375 [0.992–2.386] | 0.258 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ilic, I.; Radunovic, A.; Matic, M.; Zugic, V.; Ostojic, M.; Stanojlovic, M.; Kojic, D.; Boskovic, S.; Borzanovic, D.; Timcic, S.; et al. Acute Coronary Syndrome Presenting during On- and Off-Hours: Is There a Difference in a Tertiary Cardiovascular Center? Medicina 2023, 59, 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081420

Ilic I, Radunovic A, Matic M, Zugic V, Ostojic M, Stanojlovic M, Kojic D, Boskovic S, Borzanovic D, Timcic S, et al. Acute Coronary Syndrome Presenting during On- and Off-Hours: Is There a Difference in a Tertiary Cardiovascular Center? Medicina. 2023; 59(8):1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081420

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlic, Ivan, Anja Radunovic, Milica Matic, Vasko Zugic, Miljana Ostojic, Milica Stanojlovic, Dejan Kojic, Srdjan Boskovic, Dusan Borzanovic, Stefan Timcic, and et al. 2023. "Acute Coronary Syndrome Presenting during On- and Off-Hours: Is There a Difference in a Tertiary Cardiovascular Center?" Medicina 59, no. 8: 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081420

APA StyleIlic, I., Radunovic, A., Matic, M., Zugic, V., Ostojic, M., Stanojlovic, M., Kojic, D., Boskovic, S., Borzanovic, D., Timcic, S., Radoicic, D., Dobric, M., & Tomovic, M. (2023). Acute Coronary Syndrome Presenting during On- and Off-Hours: Is There a Difference in a Tertiary Cardiovascular Center? Medicina, 59(8), 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081420