Quality of Life and Working Conditions of Hand Surgeons—A National Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Development

2.2. Survey Content

2.3. Survey Administration

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents

3.2. Professional Details/Working Hours

3.3. Health Status

3.4. Quality of Life and Satisfaction

3.5. Significant Correlations

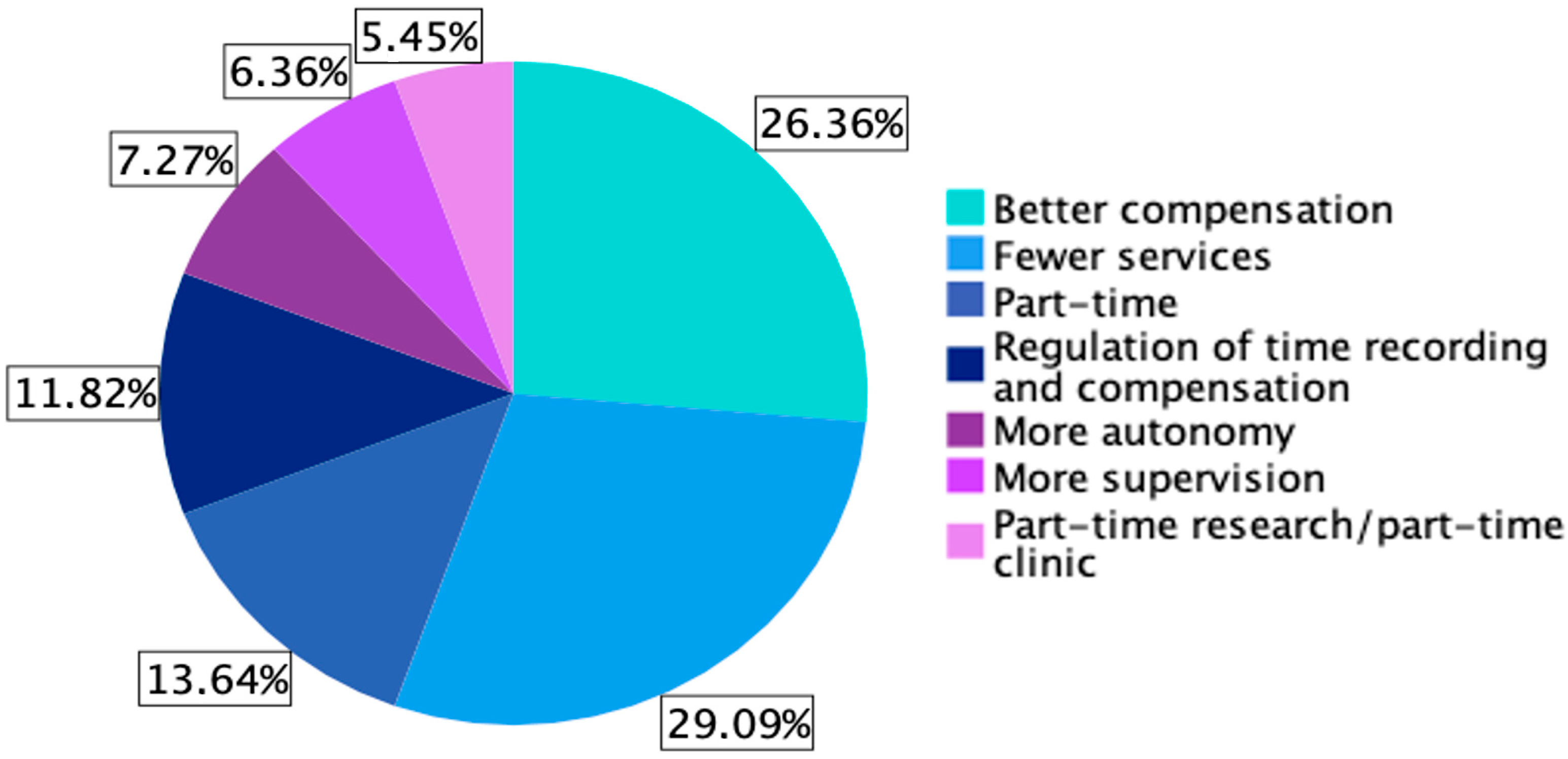

3.6. Factors That Would Make Employment at an Acute Care Hospital for Hand Surgery More Attractive

4. Discussion

4.1. Quality of Life

4.2. Burnout

4.3. Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic

4.4. Gender

4.5. Working Hours

4.6. Career Satisfaction

4.7. Working Conditions

4.8. Attractivity of Acute Care Hospitals

4.9. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cathelain, A.; Merlier, M.; Estrade, J.-P.; Duhamel, A.; Phalippou, J.; Kerbage, Y.; Collinet, P. Assessment of the quality of life of gynecologic surgeons: A national survey in France. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.H.; Moe, J.S.; Abramowicz, S. Work–Life Balance for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 33, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohrer, T.; Koller, M.; Schlitt, H.-J.; Bauer, H. Lebensqualität deutscher Chirurginnen und Chirurgen. DMW—Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2011, 136, 2140–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas Ramanathan, P.; Baldesberger, N.; Dietrich, L.G.; Speranza, C.; Lüthy, A.; Buhl, A.; Gisin, M.; Koch, R.; Nicca, D.; Suggs, L.S.; et al. Health Care Professionals’ Interest in Vaccination Training in Switzerland: A Quantitative Survey. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balch, C.M.; Shanafelt, T. Combating Stress and Burnout in Surgical Practice: A Review. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2011, 21, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, A.J.; Houk, A.K.; Pulcrano, M.; Shara, N.M.; Kwagyan, J.; Jackson, P.G.; Sosin, M. Meta-Analysis of Surgeon Burnout Syndrome and Specialty Differences. J. Surg. Educ. 2018, 75, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Balch, C.M.; Bechamps, G.; Russell, T.; Dyrbye, L.; Satele, D.; Collicott, P.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.; Freischlag, J. Burnout and Medical Errors Among American Surgeons. Ann. Surg. 2010, 251, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulcrano, M.; Evans, S.R.T.; Sosin, M. Quality of Life and Burnout Rates Across Surgical Specialties: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2016, 151, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gobari, M.; Shoman, Y.; Blanc, S.; Canu, I.G. Point prevalence of burnout in Switzerland: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2022, 152, w30229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.W.; Columbus, A.B.; Fields, A.C.; Melnitchouk, N.; Cho, N.L. Gender Differences in Surgeon Burnout and Barriers to Career Satisfaction: A Qualitative Exploration. J. Surg. Res. 2020, 247, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S.U.; Aslan, A.; Coskun, E.; Coban, B.N.; Haner, Z.; Kart, S.; Skaik, M.N.I.; Kocer, M.D.; Ozkan, B.B.; Akyol, C. Prevalence and associated factors for burnout among attending general surgeons: A national cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fainberg, J.; Lee, R.K. What Is Underlying Resident Burnout in Urology and What Can Be Done to Address this? Curr. Urol. Rep. 2019, 20, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesak, S.S.; Cutshall, S.; Anderson, A.; Pulos, B.; Moeschler, S.; Bhagra, A. Burnout Among Women Physicians: A Call to Action. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2020, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, L.C.; Jeffe, D.B.; Jin, L.; Awad, M.M.; Turnbull, I.R. National Survey of Burnout among US General Surgery Residents. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 223, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodkinson, A.; Zhou, A.; Johnson, J.; Geraghty, K.; Riley, R.; Zhou, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; A Chew-Graham, C.; Peters, D.; Esmail, A.; et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 378, e070442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akazawa, S.; Fujimoto, Y.; Sawada, M.; Kanda, T.; Nakahashi, T. Women Physicians in Academic Medicine of Japan. JMA J. 2022, 5, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mavroudis, C.L.; Landau, S.; Brooks, E.; Bergmark, R.; Berlin, N.L.; Blumenthal, B.; Cooper, Z.; Hwang, E.K.; Lancaster, E.; Waljee, J.; et al. The Relationship Between Surgeon Gender and Stress During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Surg. 2021, 273, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalafallah, A.M.; Lam, S.; Gami, A.; Dornbos, D.L.; Sivakumar, W.; Johnson, J.N.; Mukherjee, D. Burnout and career satisfaction among attending neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 198, 106193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnad, S.S.; Colletti, L.M. Issues in the recruitment and success of women in academic surgery. Surgery 2002, 132, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.M.; Irish, W.; Strassle, P.D.; Mahoney, S.T.; Schroen, A.T.; Josef, A.P.; Freischlag, J.A.; Tuttle, J.E.; Brownstein, M.R. Associations Between Career Satisfaction, Personal Life Factors, and Work-Life Integration Practices Among US Surgeons by Gender. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J.M.; Najarian, M.M.; Ties, J.S.; Borgert, A.J.; Kallies, K.J.; Jarman, B.T. Career Satisfaction, Gender Bias, and Work-Life Balance: A Contemporary Assessment of General Surgeons. J. Surg. Educ. 2021, 78, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptiste, D.; Fecher, A.M.; Dolejs, S.C.; Yoder, J.; Schmidt, C.M.; Couch, M.E.; Ceppa, D.P. Gender differences in academic surgery, work-life balance, and satisfaction. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 218, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchberg, J.; Fritzmann, J.; Clemens, J.; Oppermann, N.; Johannink, J.; Kirschniak, A.; Weitz, J.; Mees, S.T. Der leidende Chirurg—Wie schützen Chirurgen sich selbst?: DGAV-Umfrage zur Verbreitung von Arbeitssicherheitsmaßnahmen und Gesundheitsbelastung bei deutschen Chirurgen. Chirurg 2021, 92, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibble, H.M.; Broughton, N.S.; Studdert, D.M.; Spittal, M.J.; Hill, N.; Morris, J.M.; Bismark, M.M. Why do surgeons receive more complaints than their physician peers?: Complaints about surgeons and physicians. ANZ J. Surg. 2018, 88, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Number (Rate) |

|---|---|

| Age Group (years) | |

| 18–29 | 4 (3.6%) |

| 30–44 | 60 (54.6%) |

| 45–60 | 34 (30.9%) |

| 60+ | 12 (10.9%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 61 (55.5%) |

| Female | 49 (44.5%) |

| Language | |

| German | 85 (77.3%) |

| French | 23 (20.9%) |

| English | 2 (1.8%) |

| Relationship | |

| Yes | 101 (91.8%) |

| No | 9 (8.2%) |

| Children | |

| Yes | 77 (70.0%) |

| No | 33 (30.0%) |

| Characteristic | Number (Rate) |

|---|---|

| Position | |

| Resident | 25 (22.7%) |

| Senior physician | 24 (21.8%) |

| Leading position | 29 (26.4%) |

| Senior consultant/practice owner | 32 (29.1%) |

| Hospital/Practice Category | |

| Level I | 34 (30.9%) |

| Level II | 39 (35.5%) |

| Level III | 7 (6.4%) |

| Practice | 26 (23.6%) |

| Other | 4 (3.6%) |

| Quality of Life | Number (Rate) |

|---|---|

| Insufficient | 1 (0.9%) |

| Moderate | 12 (10.9%) |

| Good | 22 (20.0%) |

| Very good | 66 (60.0%) |

| Excellent | 9 (8.2%) |

| Category | Number (Rate) |

|---|---|

| Social Life | |

| Not satisfied at all | 2 (1.8%) |

| Insufficient | 20 (18.2%) |

| Moderate | 43 (39.1%) |

| Good | 35 (31.8%) |

| Completely satisfied | 10 (9.1%) |

| Family Life | |

| Not satisfied at all | 9 (8.2%) |

| Insufficient | 29 (26.4%) |

| Moderate | 49 (44.5%) |

| Good | 19 (17.3%) |

| Completely satisfied | 4 (3.6%) |

| Job/Carreer | |

| Not satisfied at all | 4 (3.6%) |

| Insufficient | 15 (13.7%) |

| Moderate | 69 (62.7%) |

| Good | 21 (19.1%) |

| Completely satisfied | 1 (0.9%) |

| Salary | |

| Not satisfied at all | 5 (4.5%) |

| Insufficient | 29 (26.4%) |

| Moderate | 30 (27.3%) |

| Good | 29 (26.4%) |

| Completely satisfied | 17 (15.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dietrich, L.G.; Vögelin, E.; Deml, M.J.; Pastor, T.; Gueorguiev, B.; Pastor, T. Quality of Life and Working Conditions of Hand Surgeons—A National Survey. Medicina 2023, 59, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081450

Dietrich LG, Vögelin E, Deml MJ, Pastor T, Gueorguiev B, Pastor T. Quality of Life and Working Conditions of Hand Surgeons—A National Survey. Medicina. 2023; 59(8):1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081450

Chicago/Turabian StyleDietrich, Léna G., Esther Vögelin, Michael J. Deml, Torsten Pastor, Boyko Gueorguiev, and Tatjana Pastor. 2023. "Quality of Life and Working Conditions of Hand Surgeons—A National Survey" Medicina 59, no. 8: 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081450

APA StyleDietrich, L. G., Vögelin, E., Deml, M. J., Pastor, T., Gueorguiev, B., & Pastor, T. (2023). Quality of Life and Working Conditions of Hand Surgeons—A National Survey. Medicina, 59(8), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59081450