Attitudes towards Exercise, Leisure Activities, and Sedentary Behavior among Adults: A Cross-Sectional, Community-Based Study in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Settings, and Population

2.2. Study Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Attitudes towards Sedentary Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tremblay, M.S.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Saunders, T.J.; Carson, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Chastin, S.F.; Altenburg, T.M.; Chinapaw, M.J. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN)—Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorp, A.A.; Owen, N.; Neuhaus, M.; Dunstan, D.W. Sedentary Behaviors and Subsequent Health Outcomes in Adults: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies, 1996–2011. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakshine, V.S.; Thute, P.; Khatib, M.N.; Sarkar, B. Increased Screen Time as a Cause of Declining Physical, Psychological Health, and Sleep Patterns: A Literary Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woessner, M.N.; Tacey, A.; Levinger-Limor, A.; Parker, A.G.; Levinger, P.; Levinger, I. The Evolution of Technology and Physical Inactivity: The Good, the Bad, and the Way Forward. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 655491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Sedentary Lifestyle: A Global Public Health Problem; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Olateju, I.V.; Opaleye-Enakhimion, T.; Udeogu, J.E.; Asuquo, J.; Olaleye, K.T.; Osa, E.; Oladunjoye, A.F. A systematic review on the effectiveness of diet and exercise in the management of obesity. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2023, 10, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Church, T.S.; Craig, C.L.; Bouchard, C. Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.W.; Barr, E.L.; Healy, G.N.; Salmon, J.; Shaw, J.E.; Balkau, B.; Magliano, D.J.; Cameron, A.J.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Owen, N. Television viewing time and mortality: The Australian diabetes, obesity and lifestyle study (AusDiab). Circulation 2010, 121, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R.; McNamara, E.; Tainio, M.; de Sá, T.H.; Smith, A.D.; Sharp, S.J.; Edwards, P.; Woodcock, J.; Brage, S.; Wijndaele, K. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 811–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kong, M.H.; Oh, Y.H. Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2020, 41, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Bulzing, R.A.; Meyer, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Grabovac, I.; Willeit, P.; Tavares, V.D.O.; Calegaro, V.C.; et al. Associations of moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behavior with depressive and anxiety symptoms in self-isolating people during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey in Brazil. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Physical Activity 2022: Web Annex: Global Action Plan on Physical Activity Monitoring Framework, Indicators and Data Dictionary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Kercher, V.M.; Kercher, K.; Levy, P.; Bennion, T.; Alexander, C.; Amaral, P.C.; Batrakoulis, A.; Chávez, L.F.; Cortés-Almanzar, P.; Haro, J.L.; et al. 2023 Fitness Trends from around the Globe. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2023, 27, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakoulis, A. European survey of fitness trends for 2020. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2019, 23, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Carty, C.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Biddle, S.J.; Bull, F.; Willumsen, J.; Lee, L.; Kamenov, K.; Milton, K. The first global physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines for people living with disability. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Musaiger, A.O. Physical activity patterns and eating habits of adolescents living in major Arab cities. The Arab Teens Lifestyle Study. Saudi Med. J. 2010, 31, 210–211. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Fact Sheet: Physical Activity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Albawardi, N.M.; Jradi, H.; Almalki, A.A.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M. Level of Sedentary Behavior and Its Associated Factors among Saudi Women Working in Office-Based Jobs in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashatah, A.; Qadhi, O.A.; Al Sadoun, A.; Syed, W.; A Al-Rawi, M.B. Evaluation of Young Adults’ Physical Activity Status and Perceived Barriers in the Riyadh Region of Saudi Arabia. J. Multidiscip. Health 2023, 16, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S.A.; Melvin, A.; Roberts, K.C.; Butler, G.P.; Thompson, W. Sedentary behaviour surveillance in Canada: Trends, challenges and lessons learned. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmed, Z.; Lobelo, F. Physical activity promotion in Saudi Arabia: A critical role for clinicians and the health care system. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2018, 7, S7–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabry, R.; Koohsari, M.J.; Bull, F.; Owen, N. A systematic review of physical activity and sedentary behaviour research in the oil-producing countries of the Arabian Peninsula. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, T.T.; Al Khoudair, A.S.; Al Harbi, M.A.; Al Ali, A.R. Leisure Time Physical Activity in Saudi Arabia: Prevalence, Pattern and Determining Factors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, A.; Nistrup, A.; Al-Rammah, T.Y.; Aro, A.R. Lack of facilities rather than sociocultural factors as the primary barrier to physical activity among female Saudi university students. Int. J. Womens Health 2015, 7, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.; Herring, M.; McDowell, C.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Schuch, F.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.; Martin, J.; Caswell, S.; et al. Joint prevalence of physical activity and sitting time during COVID-19 among US adults in April 2020. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 20, 101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zalabani, A.H.; Al-Hamdan, N.A.; Saeed, A.A. The prevalence of physical activity and its socioeconomic correlates in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional population-based national survey. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2015, 10, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nozha, M.M.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Arafah, M.R.; Al-Khadra, A.; Al-Mazrou, Y.Y.; A Al-Maatouq, M.; Khan, N.B.; Al-Marzouki, K.; Al-Harthi, S.S.; Abdullah, M.; et al. Prevalence of physical activity and inactivity among Saudis aged 30–70 years. A population-based cross-sectional study. Saudi Med. J. 2007, 28, 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Riyadh Population. 2023. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/riyadh-population (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Piggin, J. What Is Physical Activity? A Holistic Definition for Teachers, Researchers and Policy Makers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakoulis, A.; Jamurtas, A.Z.; Metsios, G.S.; Perivoliotis, K.; Liguori, G.; Feito, Y.; Riebe, D.; Thompson, W.R.; Angelopoulos, T.J.; Krustrup, P.; et al. Comparative Efficacy of 5 Exercise Types on Cardiometabolic Health in Overweight and Obese Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of 81 Randomized Controlled Trials. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 15, e008243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marconcin, P.; Zymbal, V.; Gouveia, É.R.; Jones, B.; Marques, A. Sedentary Behaviour: Definition, determinants, impacts on Health, and current recommendations. In Sedentary Behaviour—A Contemporary View; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Family Time Definition. Available online: https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/family-time#:~:text=Family%20Time%20means%20vistation%20and,who%20are%20separated%2C%20and%20grandparents (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Motuma, A.; Gobena, T.; Roba, K.T.; Berhane, Y.; Worku, A. Sedentary Behavior and Associated Factors Among Working Adults in Eastern Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 693176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcymbal, A.; Andreasyan, D.; Whiting, S.; Mikkelsen, B.; Rakovac, I.; Breda, J. Prevalence of Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior Among Adults in Armenia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.P.; Guimarães, R.d.F.; Bacil, E.D.A.; Piola, T.S.; Fantinelli, E.R.; Fontana, F.E.; de Campos, W. Time spent in different sedentary activity domains across adolescence: A follow-up study. J. Pediatr. 2022, 98, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvier, M.; Bertrais, S.; Charreire, H.; Vergnaud, A.-C.; Hercberg, S.; Oppert, J.-M. Changes in leisure-time physical activity and sedentary behaviour at retirement: A prospective study in middle-aged French subjects. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, J.; Tremblay, M.S.; Marshall, S.J.; Hume, C. Health Risks, Correlates, and Interventions to Reduce Sedentary Behavior in Young People. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, N.; Healy, G.N.; Matthews, C.E.; Dunstan, D.W. Too much sitting: The population-health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2010, 38, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshmandi, H.; Choobineh, A.; Ghaem, H.; Karimi, M. Adverse Effects of Prolonged Sitting Behavior on the General Health of Office Workers. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 7, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.M.; Black, K.M.; Korn, H.; Nordin, M. Association between sitting and occupational LBP. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, P.; Papathanasiou, G.; Georgoudis, G.; Chronopoulos, E.; Koutis, H.; Koumoutsou, F. Prevalence of low back pain in greek public office workers. Pain Physician 2007, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, M.R.; Moussavi, S.J.; Salavati, M. Effects of Lifestyle and Work-Related Physical Activity on the Degree of Lumbar Lordosis and Chronic Low Back Pain in a Middle East Population. Clin. Spine Surg. 2001, 14, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spine Care Ergonomics for Prolonged Sitting. Back Pain When Sitting. Available online: https://www.uclahealth.org/medical-services/spine/patient-resources/ergonomics-prolonged-sitting#:~:text=Sitting%20for%20prolonged%20periods%20of,back%20muscles%20and%20spinal%20discs (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Park, S.-M.; Kim, H.-J.; Jeong, H.; Kim, H.; Chang, B.-S.; Lee, C.-K.; Yeom, J.S. Longer sitting time and low physical activity are closely associated with chronic low back pain in population over 50 years of age: A cross-sectional study using the sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Spine J. 2018, 18, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Cao, Y.; Ni, S.; Chen, X.; Shen, M.; Lv, H.; Hu, J. Association of Sedentary Behavior With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicide Ideation in College Students. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 566098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, E.M.; Corcoran, P.; O’regan, G.; Keeley, H.; Cannon, M.; Carli, V.; Wasserman, C.; Hadlaczky, G.; Sarchiapone, M.; Apter, A.; et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soundy, A.; Roskell, C.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D. Selection, Use and Psychometric Properties of Physical Activity Measures to Assess Individuals with Severe Mental Illness: A Narrative Synthesis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2014, 28, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characters | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 469 | 67.7% |

| Female | 224 | 32.3% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 388 | 56% |

| Not married | 305 | 44% |

| Age (years) | ||

| 23–25 | 327 | 47.2% |

| 26–29 | 71 | 10.2% |

| 30–35 | 118 | 17% |

| 36–39 | 129 | 18.6% |

| >40 | 48 | 6.9% |

| Profession | ||

| University employee | 66 | 9.5% |

| Business Man | 20 | 2.9% |

| Student at the College of Dentistry | 40 | 5.8% |

| Working in the private sector | 50 | 7.2% |

| House Wife | 40 | 5.8% |

| Medicine Student | 145 | 20.9% |

| Working in the government sector | 194 | 28.0% |

| Pharmacy Student | 138 | 19.9% |

| Sleeping hours per day | ||

| <5 h | 11 | 1.6% |

| 5–6 h | 325 | 46.9% |

| 7–8 h | 341 | 49.2% |

| >8 h | 16 | 2.3% |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current smoker | 90 | 13% |

| Previous smoker | 68 | 9.8% |

| Never smoker | 535 | 77.2% |

| Characters | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

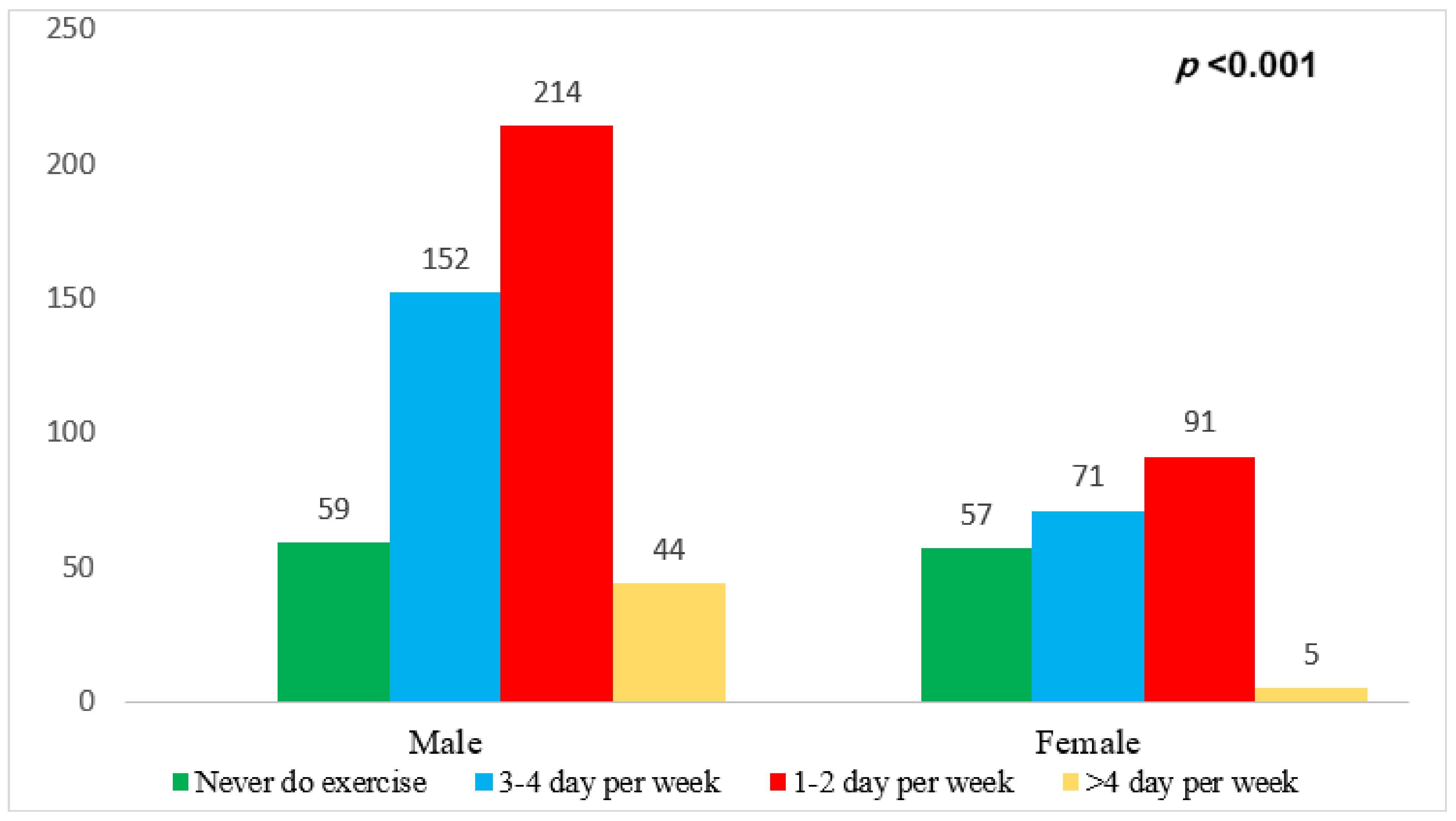

| Exercise per week | ||

| >4 days per week | 49 | 7.1% |

| 3–4 days per week | 223 | 32.2% |

| 1–2 days per week | 305 | 44% |

| Never do exercise | 116 | 16.7% |

| Sedentary time in a day | ||

| <1 h | 68 | 9.8% |

| 1–2 h | 213 | 30.7% |

| 2–3 h | 145 | 20.9% |

| 3–4 h | 173 | 25% |

| >4 h | 94 | 13.6% |

| Physical activity level per weekday | ||

| Never | 82 | 11.8% |

| Rarely | 339 | 48.9% |

| Sometimes | 119 | 17.2% |

| Always | 21 | 3.0% |

| Often | 132 | 19.0% |

| Rate your self-regarding your physical activity level per a weekend day | ||

| Never | 52 | 7.5% |

| Rarely | 340 | 49.1% |

| Sometimes | 136 | 19.6% |

| Always | 116 | 16.7% |

| Often | 49 | 7.1% |

| Rate your health state | ||

| Poor | 46 | 6.6% |

| Fair | 101 | 14.6% |

| Good | 50 | 7.2% |

| Very good | 181 | 26.1% |

| Excellent | 315 | 45.5% |

| Rate your mental-emotional state | ||

| Poor | 8 | 1.2% |

| Fair | 72 | 10.4% |

| Good | 51 | 7.4% |

| Very good | 433 | 62.5% |

| Excellent | 129 | 18.6% |

| Sedentary Hours per Day for Each Leisure Activity | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Social media | ||

| <30 min | 83 | 12% |

| 30 min | 228 | 32.9% |

| 1 h | 172 | 24.8% |

| 2 h | 85 | 12.3% |

| 3–4 h | 63 | 9.1% |

| >4 h | 62 | 8.9% |

| Business-related activity | ||

| <30 min | 207 | 29.9% |

| 30 min | 105 | 15.2% |

| 1 h | 82 | 11.8% |

| 2 h | 139 | 20.1% |

| 3–4 h | 4 | 0.6% |

| >4 h | 156 | 22.5% |

| Family time | ||

| <30 min | 51 | 7.4% |

| 30 min | 7 | 1% |

| 1 h | 53 | 7.6% |

| 2 h | 278 | 40.1% |

| 3–4 h | 265 | 38.2% |

| >4 h | 39 | 5.6% |

| Watching TV | ||

| <30 min | 372 | 53.7% |

| 30 min | 167 | 24.1% |

| 1 h | 75 | 10.8% |

| 2 h | 55 | 7.9% |

| 3–4 h | 2 | 0.3% |

| >4 h | 22 | 3.2% |

| Video games | ||

| <30 min | 542 | 78.2% |

| 30 min | 8 | 1.2% |

| 1 h | 14 | 2.0% |

| 2 h | 89 | 12.8% |

| 3–4 h | 37 | 5.3% |

| >4 h | 3 | 0.4% |

| Work-related activities | ||

| <30 min | 48 | 6.9% |

| 30 min | 8 | 1.2% |

| 1 h | 83 | 12% |

| 2 h | 17 | 2.5% |

| 3–4 h | 107 | 15.4% |

| >4 h | 430 | 62% |

| Coffee time | ||

| <30 min | 70 | 10.1% |

| 30 min | 71 | 10.2% |

| 1 h | 58 | 8.4% |

| 2 h | 198 | 28.6% |

| 3–4 h | 44 | 6.3% |

| >4 h | 252 | 36.4% |

| Variables | Physical Activity Level per a Week | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Often n (%) | Always n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Rarely n (%) | Never n (%) | |||

| Sleeping hours | |||||||

| <5 h | Count | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 3 | <0.001 |

| % within Sleeping hours per day | 0.0% | 0.0% | 54.5% | 18.2% | 27.3% | ||

| 5–6 h | Count | 90 | 8 | 32 | 121 | 74 | |

| % within Sleeping hours per day | 27.7% | 2.5% | 9.8% | 37.2% | 22.8% | ||

| 7–8 h | Count | 42 | 9 | 80 | 206 | 4 | |

| % within Sleeping hours per day | 12.3% | 2.6% | 23.5% | 60.4% | 1.2% | ||

| >8 h | Count | 0 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 1 | |

| % within Sleeping hours per day | 0.0% | 25.0% | 6.3% | 62.5% | 6.3% | ||

| Age(In years) | |||||||

| 23–25 | Count | 127 | 0 | 41 | 158 | 1 | <0.001 |

| % within Age | 38.8% | 0.0% | 12.5% | 48.3% | 0.3% | ||

| 26–29 | Count | 1 | 2 | 30 | 4 | 34 | |

| % within Age | 1.4% | 2.8% | 42.3% | 5.6% | 47.9% | ||

| 30–35 | Count | 1 | 3 | 11 | 64 | 39 | |

| % within Age | 0.8% | 2.5% | 9.3% | 54.2% | 33.1% | ||

| 36–39 | Count | 0 | 3 | 23 | 99 | 4 | |

| % within Age | 0.0% | 2.3% | 17.8% | 76.7% | 3.1% | ||

| >40 | Count | 3 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 4 | |

| % within Age | 6.3% | 27.1% | 29.2% | 29.2% | 8.3% | ||

| Physical Activity per week | Health State | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent n (%) | Very Good n (%) | Good n (%) | Fair n (%) | Poor n (%) | |||

| Often | Count | 129 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 97.7% | 2.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||

| Always | Count | 4 | 13 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 19.0% | 61.9% | 4.8% | 14.3% | 0.0% | ||

| Sometimes | Count | 70 | 12 | 31 | 5 | 1 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 58.8% | 10.1% | 26.1% | 4.2% | 0.8% | ||

| Rarely | Count | 111 | 118 | 16 | 91 | 3 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 32.7% | 34.8% | 4.7% | 26.8% | 0.9% | ||

| Never | Count | 1 | 35 | 2 | 2 | 42 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 1.2% | 42.7% | 2.4% | 2.4% | 51.2% | ||

| Physical Activity per Week | Profession | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Businessman n (%) | Housewife n (%) | Students n (%) | University Employee n (%) | Government Employee n (%) | Private Employee n (%) | |||

| Often | Count | 0 | 0 | 127 | 1 | 3 | 1 | <0.001 |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 0.0% | 0.0% | 96.2% | 0.8% | 2.3% | 0.8% | ||

| Always | Count | 0 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 2 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 0.0% | 9.5% | 0.0% | 81.0% | 0.0% | 9.5% | ||

| Sometimes | Count | 20 | 1 | 39 | 22 | 34 | 3 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 16.8% | 0.8% | 32.8% | 18.5% | 28.6% | 2.5% | ||

| Rarely | Count | 0 | 2 | 156 | 18 | 121 | 42 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 0.0% | 0.6% | 46.0% | 5.3% | 35.7% | 12.4% | ||

| Never | Count | 0 | 35 | 1 | 8 | 36 | 2 | |

| % within physical activity level per weekday | 0.0% | 42.7% | 1.2% | 9.8% | 43.9% | 2.4% | ||

| Statements | Strongly Agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Strongly Disagree n (%) | Mean (Std) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting for long periods can be harmful to health. | 467 (67.4) | 89 (12.8) | 56 (8.1) | 77 (11.1) | 4 (0.6) | 3.32 (1.106) |

| Sitting for prolonged periods will not negatively impact my health if I regularly exercise during the day | 13 (1.9) | 209 (30.2) | 311 (44.8) | 128 (18.5) | 32 (4.6) | 2.32 (1.067) |

| Sitting for prolonged periods can negatively impact my Mental and emotional state | 132 (19) | 444 (64.1) | 68 (9.8) | 44 (6.3) | 5 (0.7) | 1.86 (1.244) |

| There is a strong relationship between backpain and prolonged sitting hours | 421 (60.8) | 128 (18.5) | 95 (13.7) | 43 (6.2) | 6 (0.9) | 3.19 (1.186) |

| There is a strong relationship between social media and prolonged sitting hours | 131 (18.9) | 364 (52.5) | 108 (15.6) | 87 (12.6) | 3 (0.4) | 2.02 (1.216) |

| There is a strong relationship between coffee-dessert time and prolonged sitting hours | 120 (17.3) | 286 (41.3) | 177 (25.5) | 103 (14.9) | 7 (1.0) | 2.22 (1.186) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bashatah, A.; Ali, W.S.; Al-Rawi, M.B.A. Attitudes towards Exercise, Leisure Activities, and Sedentary Behavior among Adults: A Cross-Sectional, Community-Based Study in Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2023, 59, 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091524

Bashatah A, Ali WS, Al-Rawi MBA. Attitudes towards Exercise, Leisure Activities, and Sedentary Behavior among Adults: A Cross-Sectional, Community-Based Study in Saudi Arabia. Medicina. 2023; 59(9):1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091524

Chicago/Turabian StyleBashatah, Adel, Wajid Syed Ali, and Mahmood Basil A. Al-Rawi. 2023. "Attitudes towards Exercise, Leisure Activities, and Sedentary Behavior among Adults: A Cross-Sectional, Community-Based Study in Saudi Arabia" Medicina 59, no. 9: 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091524

APA StyleBashatah, A., Ali, W. S., & Al-Rawi, M. B. A. (2023). Attitudes towards Exercise, Leisure Activities, and Sedentary Behavior among Adults: A Cross-Sectional, Community-Based Study in Saudi Arabia. Medicina, 59(9), 1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59091524