Assessment of Hypersensitivity to House Dust Mites in Selected Skin Diseases Using the Basophil Activation Test: A Preliminary Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Skin Prick Tests

2.2.2. Skin Contact Tests

2.2.3. sIgE Assay

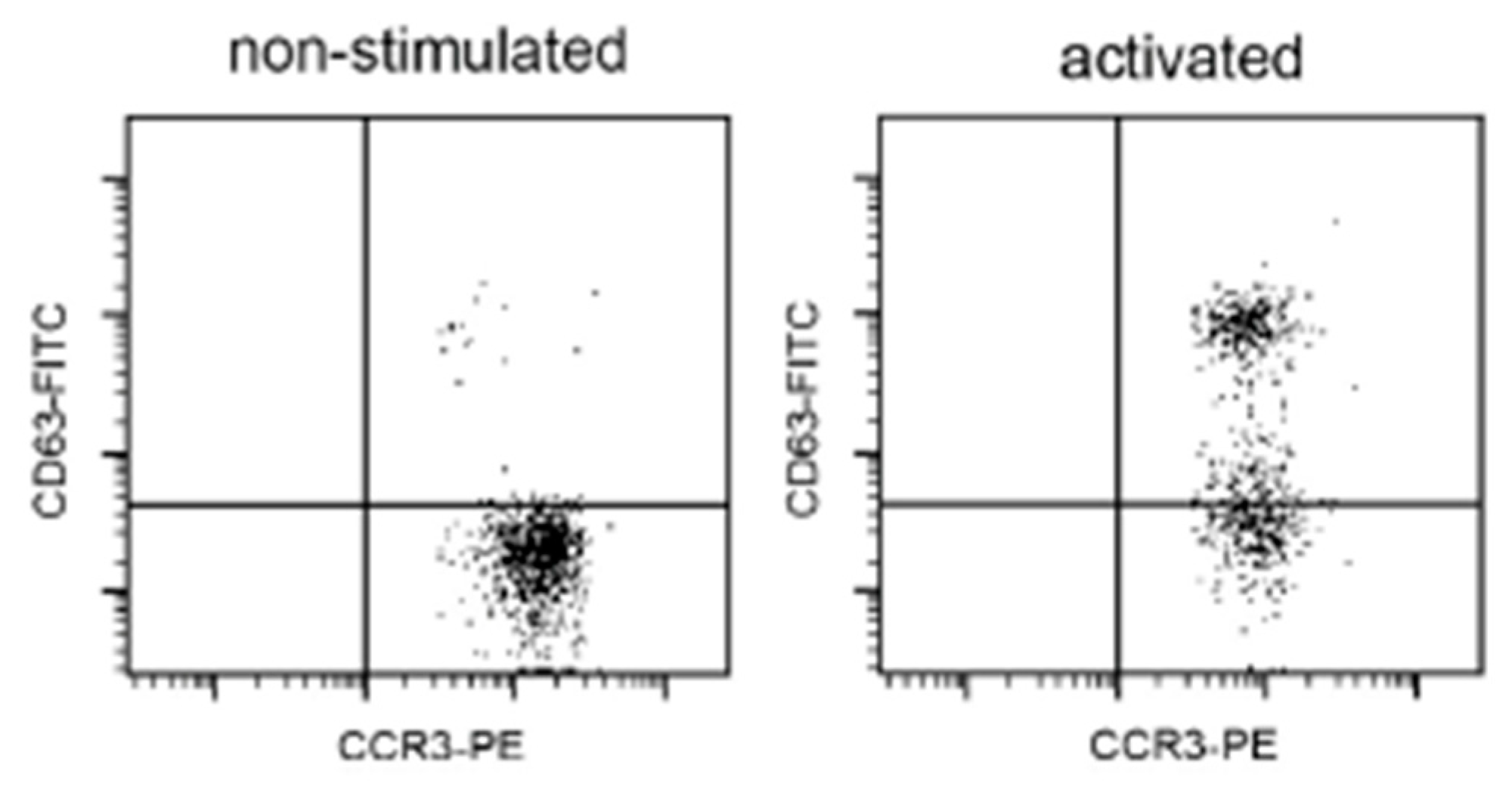

2.3. Basophil Activation Test (BAT)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vitiello, G.; Biagioni, B.; Parronchi, P. The multiple roles of mite allergens in allergic diseases. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 19, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporik, R.; Holgate, S.T.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E.; Cogswell, J.J. Exposure house-dust mite allergen (Der p I) and the development of asthma in childhood. A prospective study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloun, A.; León, B. Sensing of protease activity as a triggering mechanism of Th2 cell immunity and allergic disease. Front. Allergy 2023, 4, 1265049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, W.R.; Hales, B.J. T and B cell responses to HDM allergens and antigens. Immunol. Res. 2007, 37, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutel, M.; Agache, I.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Akdis, M.; Chivato, T.; Del Giacco, S.; Gajdanowicz, P.; Gracia, I.E.; Klimek, L.; Lauerma, A.; et al. Nomenclature of allergic diseases and hypersensitivity reactions: Adapted to modern needs: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2023, 78, 2851–2874, Erratum in: Allergy 2024, 79, 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicki, R.; Trzeciak, M.; Wilkowska, A.; Sokołowska-Wojdyło, M.; Ługowska-Umer, H.; Barańska-Rybak, W.; Kaczmarski, M.; Kowalewski, C.; Kruszewski, J.; Maj, J.; et al. Atopic dermatitis: Current treatment guidelines. Statement of the experts of the Dermatological Section, Polish Society of Allergology, and the Allergology Section, Polish Society of Dermatology. Post. Dermatol. Alergol. 2015, 32, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Enos, C.W.; Lam, K.K.; Han, J.K. The Role of Inhalant Allergens on the Clinical Manifestations of Atopic Dermatitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2024, 38, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumbacea, R.S.; Corcea, S.L.; Ali, S.; Dinica, L.C.; Fanfaret, I.S.; Boda, D. Mite allergy and atopic dermatitis: Is there a clear link? (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 3554–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diepgen, T.L.; Andersen, K.E.; Chosidow, O.; Coenraads, P.J.; Elsner, P.; English, J.; Fartasch, M.; Gimenez-Arnau, A.; Nixon, R.; Sasseville, D.; et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hand eczema. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2015, 13, e1–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loman, L.; Brands, M.J.; Massella Patsea, A.A.L.; Politiek, K.; Arents, B.W.M.; Schuttelaar, M.L.A. Lifestyle factors and hand eczema: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Contact Dermat. 2022, 87, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schuttelaar, M.L.; Coenraads, P.J.; Huizinga, J.; De Monchy, J.G.; Vermeulen, K.M. Increase in vesicular hand eczema after house dust mite inhalation provocation: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Contact Dermat. 2013, 68, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankiewicz-Sojka, K.; Czerwionka-Szaflarska, M. Frequency of contact allergy to house dust mites in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Pol.-Pol. J. Paediatr. 2022, 97, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, H.M.; Jha, R.K. Triggered Skin Sensitivity: Understanding Contact Dermatitis. Cureus 2024, 16, e59486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.F.; Alpan, O.; Hoffmann, H.J. Basophil activation test: Mechanisms and considerations for use in clinical trials and clinical practice. Allergy 2021, 76, 2420–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberlein, B. Basophil Activation as Marker of Clinically Relevant Allergy and Therapy Outcome. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Atopic Dermatitis n = 52 | Hand Eczema n = 57 | Healthy Controls n = 68 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age: yrs ± SD | 36.1 ± 6.9 | 40.8 ± 9.1 * | 33.2 ± 10.3 | 0.04 |

| women (%) | 57.4% | 60.1% | 55.1% | <0.05 |

| duration of disease: yrs ± SD | 12.9 ± 10.1 | 10.1 ± 4.7 | - | <0.05 |

| BMI ± SD | 23.6 ± 2.7 | 26.8 ± 5.7 * | 24.1 ± 3.2 | 0.02 |

| current or former smokers (%) | 24.6% | 28.1% | 26.8% | <0.05 |

| total IgE kU/L ± SD | 456.1 ± 106.3 ** | 59.1 ± 30.3 | 44.6 ± 28.1 | 0.001 |

| asthma allergy (%) | 27.1% ** | 4.7% | 0 | 0.004 |

| rhinitis allergy (%) | 78.1% ** | 9.2% | 0 | 0.003 |

| atopy in family (%) | 23.7% ** | 8.1% | 4.5% | 0.02 |

| polysentization (%) | 39.2% ** | 1.2% | 0 | 0.003 |

| inhalant allergens | ||||

| most frequently | ||||

| confirmed: | ||||

| grass pollen | 11.5% | 1.5% | 0 | |

| trees pollen | 7.4% | 1.1% | 0.5% | |

| cat | 2.3% | 0 | ||

| food allergy | 24.7% ** | 0 | 0 | 0.003 |

| Positive Results | Atopic Dermatitis n = 52 | Hand Eczema n = 57 | Healthy Controls n = 68 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPT | 28 (53.8%) | 11 (19.3%) | 1 (0.01%) | <0.05 |

| sIgE | 32 (61.5%) | 6 (10.5%) | 1 (0.01%) | <0.05 |

| BAT | 34 (65.4%) | 14 (24.6)%) | 0 | <0.05 |

| mean percentage increase of activated CD63 basophils | 74.6% | 68.1% | 2.8% | |

| correlation r * | 0.72 | 0.85 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krupka Olek, M.; Bożek, A.; Foks Ciekalska, A.; Grzanka, A.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Assessment of Hypersensitivity to House Dust Mites in Selected Skin Diseases Using the Basophil Activation Test: A Preliminary Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101608

Krupka Olek M, Bożek A, Foks Ciekalska A, Grzanka A, Kawczyk-Krupka A. Assessment of Hypersensitivity to House Dust Mites in Selected Skin Diseases Using the Basophil Activation Test: A Preliminary Study. Medicina. 2024; 60(10):1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101608

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrupka Olek, Magdalena, Andrzej Bożek, Aleksandra Foks Ciekalska, Alicja Grzanka, and Aleksandra Kawczyk-Krupka. 2024. "Assessment of Hypersensitivity to House Dust Mites in Selected Skin Diseases Using the Basophil Activation Test: A Preliminary Study" Medicina 60, no. 10: 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101608

APA StyleKrupka Olek, M., Bożek, A., Foks Ciekalska, A., Grzanka, A., & Kawczyk-Krupka, A. (2024). Assessment of Hypersensitivity to House Dust Mites in Selected Skin Diseases Using the Basophil Activation Test: A Preliminary Study. Medicina, 60(10), 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60101608