From Anxiety to Hardiness: The Role of Self-Efficacy in Spanish CCU Nurses in the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

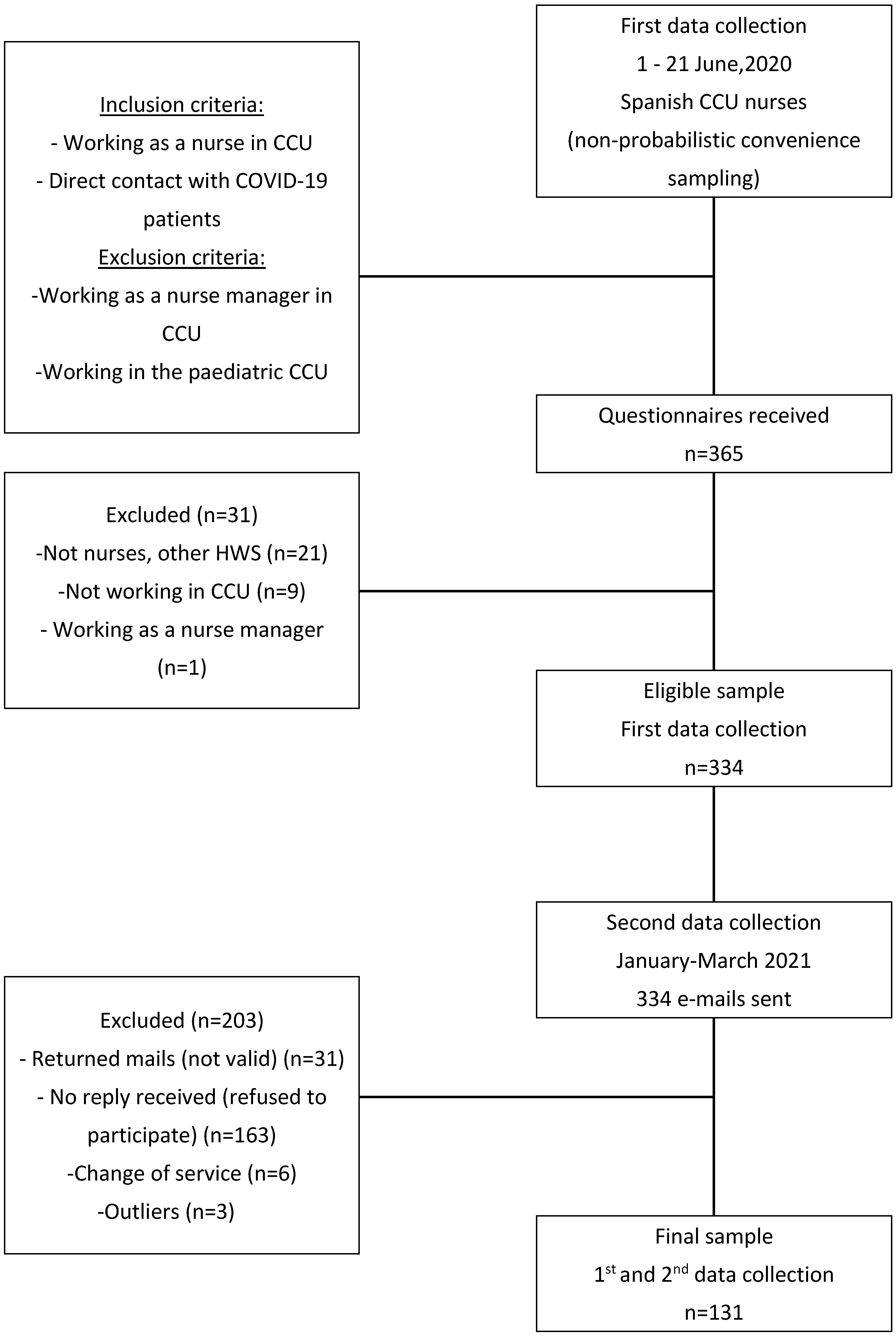

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Variables and Data Collection

2.1.1. Outcome Variables

2.1.2. Covariates

2.1.3. Data Analysis

2.2. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between Variables

3.3. Relationship of Anxiety, Self-Efficacy and Hardiness with Socio-Demographic and Employment Variables: Covariate Analysis

3.4. Mediation Analysis: Prediction of Hardiness Based on Anxiety as an Antecedent and Proposing Self-Efficacy as a Mediator

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.; Schroeder, S.; Leighton, K. Anxiety, depression, stress, burnout, and professional quality of life among the hospital workforce during a global health pandemic. J. Rural. Health 2022, 38, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buselli, R.; Corsi, M.; Baldanzi, S.; Chiumiento, M.; Del Lupo, E.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Massimetti, G.; Dell’Osso, L.; Cristaudo, A.; et al. Professional quality of life and mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Ma, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Yao, L.; Bai, H.; Cai, Z.; Yang, B.X.; et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Hedrera, F.J.; Gil-Almagro, F.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; Catalá-Mesón, P.; Velasco-Furlong, L. Intensive care unit professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: Social and work-related variables, COVID-19 symptoms, worries, and generalized anxiety levels. Acute Crit. Care 2021, 36, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Almagro, F.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; García-Hedrera, F.J.; Catalá-Mesón, P. Concern about contagion and distress in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Motherhood as moderator. Women Health 2022, 62, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Al-Lenjawi, B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 141, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, N.E.; Crowe, L.; Abbenbroek, B.; Elliott, R.; Tian, D.H.; Donaldson, L.H.; Fitzgerald, E.; Flower, O.; Grattan, S.; Harris, R.; et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on critical care healthcare workers’ depression, anxiety, and stress levels. Aust. Crit. Care Off. J. Confed. Aust. Crit. Care Nurses 2021, 34, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, E. Posttraumatic growth and positive determinants in nursing students after COVID-19 alarm status: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Sun, C.; Chen, J.J.; Jen, H.J.; Kang, X.L.; Kao, C.C.; Chou, K.R. A Large-Scale Survey on Trauma, Burnout, and Posttraumatic Growth among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, S.K.; Fritz, J.; Sopp, M.R.; Kunzler, A.M.; von Boros, L.; Tüscher, O.; Göritz, A.S.; Lieb, K.; Michael, T. Interrelations of resilience factors and their incremental impact for mental health: Insights from network modeling using a prospective study across seven timepoints. Transl. Psych. 2023, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobasa, S.C.; Maddi, S.R.; Kahn, S. Hardiness and health: A prospective study. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 42, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keane, A.; Ducette, J.; Adler, D.C. Stress in ICU and non-ICU nurses. Nurs. Res. 1985, 34, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Servellen, G.; Topf, M.; Leake, B. Personality hardiness, work-related stress, and health in hospital nurses. Hosp. Top. 1994, 72, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daines, P.A. Personality hardiness: An essential attribute for the ICU nurse? Dynamics 2000, 11, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Raphael, D.; Mackay, L.; Smith, M.; King, A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, S.R. The story of Hardiness: Twenty years of theorizing, research, and practice. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2002, 54, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehall, L.; Rush, R.; Górska, S.; Forsyth, K. The General Self-Efficacy of Older Adults Receiving Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-C.; Liang, J.-C. Relationships among Affect, Hardiness and Self-Efficacy in First Aid Provision by Airline Cabin Crew. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, R.; Arora, M. Perceived stress, self-efficacy, coping strategies and hardiness as predictors of depression. J. Psychosoc. Res. 2017, 12, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Nordmo, M.; Sørlie, H.O.; Lang-Ree, O.C.; Fosse, T. Decomposing the effect of hardiness in military leadership selection and the mediating role of self-efficacy beliefs. Mil. Psychol. 2022, 34, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Rísquez, M.I.; Sánchez Meca, J.; Godoy Fernández, C. Hardy personality, self-efficacy, and general health in nursing professionals of intensive and emergency services. Psicothema 2010, 22, 600–605. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.J.; Dawkins, D.; Hampton, M.D.; McNiesh, S. Experiences of critical care nurses during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosmans, M.W.G.; van der Knaap, L.M.; van der Velden, P.G. The predictive value of trauma-related coping self-efficacy for posttraumatic stress symptoms: Differences between treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking victims. Psychol. Trauma 2016, 8, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.R.M.; Leoni, P.H.T.; Carvalho, R.A.G.D.; Ventura, C.A.A.; Reis, R.K.; Gir, E. Resilience, depression and self-efficacy among Brazilian nursing professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2023, 28, 2941–2950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shahrour, G.; Dardas, L.A. Acute stress disorder, coping self-efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID-19. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1686–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; Fernández-Fernández, B.; Carmona-Torres, J.M.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; Romero-Gómez, B.; Rodríguez-Cañamero, S.; Barroso-Corroto, E.; Santacruz-Salas, E. Longitudinal Study of the Mental Health, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Stress of Senior Nursing Students to Nursing Graduates during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubin, J.; Delmas, P.; Gilles, I.; Oulevey Bachmann, A.; Ortoleva Bucher, C. Factors protecting Swiss nurses’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, F.J.; Martín, M.B.G.; Falcón, J.C.S.; González, P.O. The hierarchical factor structure of the Spanish version of Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2017, 17, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, J.; Crawford, J. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, P.S.; García, A.M.P.; Moreno, J.B. Escala de autoeficacia general: Datos psicométricos de la adaptación para población española. Psicothema 2000, 12, 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- De Las Cuevas, C.; Peñate, W. Validation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale in psychiatric outpatient care. Psicothema 2015, 27, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Garrosa Hernández, E.; Blanco, L.M. Development and validation of the Occupational Hardiness Questionnaire. Psicothema 2014, 26, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wagnild, G.M. The Resilience Scale User’s Guide for the US English Version of the Resilience Scale and the 14-Item Resilience Scale; The Resilience Center: Rochester, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 27.0; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, J.; Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Journal of Educational Measurement; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 51, pp. 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimino, K.; Horan, K.M.; Stephenson, C. Leading Our Frontline HEROES through Times of Crisis with a Sense of Hope, Efficacy, Resilience, and Optimism. Nurse Lead 2020, 18, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Mei, S. Effect of Psychological Intervention on Perceived Stress and Positive Psychological Traits among Nursing Students: Findings during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2022, 60, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, N.; Weston, D.; Hall, C.; Caulfield, T.; Williamson, V.; Fong, K. Mental health of staff working in intensive care during COVID-19. Occup. Med. 2021, 71, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Yi, S.; Lin, Y. The Psychological Status and Self-Efficacy of Nurses during COVID-19 Outbreak: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Inquiry 2020, 57, 46958020957114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Sharour, L.; Salameh, A.B.; Suleiman, K.; Subih, M.; El-Hneiti, M.; Al-Hussami, M.; Al Dameery, K.; Al Omari, O. Nurses’ Self-Efficacy, Confidence and Interaction with Patients with COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P.T.; McDonald, K.; Hansma, B.J.; Solomon, J. Hardiness moderates the effects of COVID-19 stress on anxiety and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 317, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phungsoonthorn, T.; Charoensukmongkol, P. How does mindfulness help university employees cope with emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 crisis? The mediating role of psychological hardiness and the moderating effect of workload. Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, M.; Karakurt, N. The impact of psychological hardiness on intolerance of uncertainty in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 3574–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetti, V.; Durante, A.; Ambrosca, R.; Arcadi, P.; Graziano, G.; Pucciarelli, G.; Simeone, S.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Cicolini, G. Anxiety, sleep disorders and self-efficacy among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: A large cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaumie, L.; Boiral, O.; Champagne, J. A mixed-methods systematic review of the effects of mindfulness on nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1017–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, S.; Sahu, M.; Govindan, R.; Nattala, P.; Gandhi, S.; Sudhir, P.M.; Balachandran, R. Psychological preparedness for pandemic (COVID-19) management: Perceptions of nurses and nursing students in India. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupcewicz, E.; Rachubińska, K.; Gaworska-Krzemińska, A.; Andruszkiewicz, A.; Kuźmicz, I.; Kozieł, D.; Grochans, E. Loneliness and Optimism among Polish Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediatory Role of Self-Efficacy. Healthcare 2022, 10, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egerod, I.; Kaldan, G.; Nordentoft, S.; Larsen, A.; Herling, S.F.; Thomsen, T.; Endacott, R. Skills, competencies, and policies for advanced practice critical care nursing in Europe: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 54, 103142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiain Erro, M.C. La competencia profesional y la acreditación de enfermeras en el cuidado del paciente crítico. Enfermería Intensiv. 2005, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.J.; Bartone, P.T. Hardiness: Making Stress Work for You to Achieve Your Life Goals; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A.; Alarcon, G.M. A meta-analytic examination of hardiness. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2010, 17, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartone, P.T.; Eid, J.; Hystad, S.W. Training hardiness for stress resilience. In Military Psychology: Concepts, Trends and Interventions; Sage: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi, A.; Abu Talib, M.; Yaacob, S.N.; Ismail, Z. Hardiness as a mediator between perceived stress and happiness in nurses. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, K.; Roche, M.; Delgado, C.; Cuzzillo, C.; Giandinoto, J.-A.; Furness, T. Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of international literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewska, A.M.; Zwierzchowska, M. Personality Traits, Personal Values, and Life Satisfaction among Polish Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datu, J.A.D.; Fincham, F.D. Gratitude, relatedness needs satisfaction, and negative psychological outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A short-term longitudinal study. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 2525–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, R.; Brandão, T.; Hipólito, J.; Ros, A.; Nunes, O. Emotion regulation, resilience, and mental health: A mediation study with university students in the pandemic context. Psychol. Sch. 2024, 61, 304–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Lin, W.; Yang, J.; Huang, P.; Li, B.; Zhang, X. How social support predicts anxiety among university students during COVID-19 control phase: Mediating roles of self-esteem and resilience. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2022, 22, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Xie, J.; Owusua, T.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Qin, C.; He, Q. Is psychological flexibility a mediator between perceived stress and general anxiety or depression among suspected patients of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19)? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 183, 111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.S.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.H. Factors Associated with Post-traumatic Growth among Healthcare Workers Who Experienced the Outbreak of MERS Virus in South Korea: A Mixed-Method Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 541510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, C.; Yang, B.X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Lai, J.; Ma, X.; et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner-Puntonet, M.; Fidel-Kinori, S.G.; Beneria, A.; Delgado-Arroyo, M.; Perea-Ortueta, M.; Closa-Castells, M.H.; Estelrich-Costa, M.D.L.N.; Daigre, C.; Valverde-Collazo, M.F.; Bassas-Bolibar, N.; et al. La Atención a las Necesidades en Salud Mental de los Profesionales Sanitarios durante la COVID-19. Clínica Salud 2021, 32, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, W. Recommended psychological crisis intervention response to the 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak in China: A model of West China Hospital. Precis. Clin. Med. 2020, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasalvia, A.; Bonetto, C.; Porru, S.; Carta, A.; Tardivo, S.; Bovo, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Amaddeo, F. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 30, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnie, A.; Moura, K.; Moura, C.; D’Aragon, F.; Tsang, J.L.Y. Psychosocial distress amongst Canadian intensive care unit healthcare workers during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, C.; Montero, M.; Serrano-Ibáñez, E.R.; de la Vega, A.; Pulido, M.A.G. Psychological interventions for healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2023, 39, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreres-Galán, V.; Navarro-Haro, M.V.; Peris-Baquero, Ó.; Guillén-Marín, S.; de Luna-Hermoso, J.; Osma, J. Assessment of Acceptability and Initial Effectiveness of a Unified Protocol Prevention Program to Train Emotional Regulation Skills in Female Nursing Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol-DeRoque, M.A.; Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Jiménez, R.; Zamanillo-Campos, R.; Yáñez-Juan, A.M.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Leiva, A.; Gervilla, E.; García-Buades, M.E.; García-Toro, M.; et al. A Mobile Phone-Based Intervention to Reduce Mental Health Problems in Health Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic (PsyCovidApp): Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e27039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moench, J.; Billsten, O. Randomized Controlled Trial: Self-Care Traumatic Episode Protocol (STEP), Computerized EMDR Treatment of COVID-19 Related Stress. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2021, 15, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshadi Bostanabad, M.; Namdar Areshtanab, H.; Shabanloei, R.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Hogan, U.; Brittain, A.C.; Pourmahmood, A. Clinical competency and psychological empowerment among ICU nurses caring for COVID-19 patients: A cross-sectional survey study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2488–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Song, J.; Noh, W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of global health competency improvement programs on nurses and nursing students. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1552–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Pilger, S.; Olbrecht, T.; Claassen, K. Qualitative evaluation of a brief positive psychological online intervention for nursing staff. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2023, 44, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | Mean | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 40.54 | 10.02 | |||

| Experience CCU | 11.76 | 9.34 | |||

| Gender | Male | 15 | 11.45 | ||

| Female | 116 | 88.50 | |||

| Transfer to CCU 1 | Yes | 29 | 22.10 | ||

| No | 102 | 77.86 | |||

| Family status | Married | 88 | 67.18 | ||

| Single | 34 | 25.95 | |||

| Separated | 9 | 6.87 | |||

| Education level 2 | Bachelor’s or equivalent (level 6) | 88 | 67.20 | ||

| Master’s or equivalent (level 7) | 38 | 29 | |||

| Doctorate or equivalent (level 8) | 5 | 3.8 | |||

| Employment | Permanent contract | 78 | 59.50 | ||

| status | Interim | 28 | 21.40 | ||

| Temporary contract | 25 | 19.10 | |||

| Work shift | Rotational | 57 | 43.50 | ||

| Greater than 10 h | 47 | 35.90 | |||

| Fixed shift M/A/N 3 | 22 | 16.80 | |||

| Shift 12 h/Wards | 5 | 3.80 |

| Mean | SD | 95% CI | Median | IQR | Sample Range | Asymmetry | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 6.10 | 3.95 | 5.42–6.79 | 6 | 5 | 0–17 | 0.507 | −0.273 | 0.81 |

| Self-efficacy | 29.20 | 3.33 | 28.62–29.78 | 30 | 3 | 20–40 | −0.017 | 1.955 | 0.86 |

| Hardiness | 66.52 | 9.60 | 64.86–68.18 | 65 | 13 | 27–84 | −0.512 | 1.338 | 0.82 |

| Resilience | 78.03 | 14.39 | 75.54–80.51 | 81 | 14 | 14–98 | −1.611 | 3.504 | 0.94 |

| Anxiety | Self-Efficacy | Hardiness | Resilience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 1 | −0.387 (p < 0.001) | −0.193 (p = 0.027) | −0.242 (p = 0.005) |

| Self-efficacy | 1 | 0.495 (p < 0.001) | 0.504 (p < 0.001) | |

| Hardiness | 1 | 0.408 (p < 0.001) | ||

| Resilience | 1 |

| Anxiety | Self-Efficacy | Hardiness | Resilience | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | R2 = −0.273 p = 0.002 | R2 = 0.035 p = 0.696 | R2 = 0.015 p = 0.864 | R2 = −0.020 p = 0.820 | |

| Gender | woman (n = 116) | Mean = 6.40 (SD = 3.99) | Mean = 29.11 (SD = 3.35) | Mean = 66.15 (SD = 9.62) | Mean = 78 (SD = 13.94) |

| man (n = 15) | Mean = 3.80 (SD = 2.80) p = 0.016 | Mean = 29.93 (SD = 3.23) p = 0.372 | Mean = 69.40 (SD = 9.21) p = 0.218 | Mean = 78.26 (SD = 18.09) p = 0.946 | |

| Work shift | permanent (n = 22) | Mean = 6.13 (SD = 3.24) | Mean = 29.50 (SD = 3) | Mean = 66.31 (SD = 7.44) | Mean = 80.63 (SD = 11.61) |

| non-permanent (n = 108) | Mean = 6.08 (SD = 4.11) p = 0.955 | Mean = 29.21 (SD = 3.35) p = 0.711 | Mean = 66.68 (SD = 9.98) p = 0.844 | Mean = 77.89 (SD = 14.40) p = 0.402 | |

| cohabitation status | with a partner (n = 88) | Mean = 5.85 (SD = 3.77) | Mean = 29.52 (SD = 3.07) | Mean = 66.53 (SD = 9.75) | Mean = 78.42 (SD = 15.41) |

| without a partner (n = 43) | Mean = 6.62 (SD = 4.30) p = 0.294 | Mean = 28.55 (SD = 3.76) p = 0.121 | Mean = 66.51 (SD = 9.38) p = 0.990 | Mean = 77.23 (SD = 12.16) p = 0.659 | |

| years of experience in the CCU | R2 = −0.173 p = 0.048 | R2 = 0.079 p = 0.371 | R2 = 0.066 p = 0.457 | R2 = 0.032 p = 0.720 |

| Effects of Anxiety on Self-Efficacy (X → M) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VD: Self-Efficacy (M) | B (SE) | t | p | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| VI: Anxiety (X) | −0.248 (0.068) | −3.632 | <0.001 | −0.383 | −0.113 |

| Gender (covariate) | −0.219 (0.787) | −0.278 | 0.780 | −1.778 | 1.339 |

| Age (covariate) | −0.030 (0.036) | −0.856 | 0.393 | −0.101 | 0.040 |

| Work experience in years (covariate) | 0.027 (0.037) | 0.716 | 0.474 | −0.047 | 0.101 |

| Baseline Resilience (covariate) | 0.099 (0.017) | 5.653 | <0.001 | 0.064 | 0.134 |

| Model Summary R = 0.578 R2 = 0.334 F = 12.469 p < 0.001 | |||||

| Effects of Anxiety and Self-Efficacy on Hardiness (X + M → Y) | |||||

| VD: Hardiness (Y) | B (SE) | t | p | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Lower | ||||

| VI: Anxiety (X) | −0.053 (0.215) | 0.248 | 0.804 | −0.372 | 0.479 |

| M: Self-efficacy (M) | 1.108 (0.268) | 4.12 | <0.001 | 0.577 | 1.640 |

| Gender (covariate) | −2.477 (2.35) | −1.051 | 0.294 | −7.140 | 2.185 |

| Age (covariate) | −0.029 (0.107) | −0.273 | 0.784 | −0.242 | 0.183 |

| Work experience in years (covariate) | 0.051 (0.113) | 0.451 | 0.652 | −0.172 | 0.274 |

| Baseline Resilience (covariate) | 0.145 (0.059) | 2.456 | 0.015 | 0.028 | 0.262 |

| Model Summary R = 0.536 R2 = 0.287 F = 8.269 p < 0.001 | |||||

| Effects of Anxiety on Hardiness (X → Y) | |||||

| VD: Hardiness (Y) | B (SE) | t | p | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Lower | ||||

| VI: Anxiety (X) | −0.222 (0.217) | −1.022 | 0.308 | −0.652 | 0.208 |

| Gender (covariate) | −2.721 (2.502) | −1.087 | 0.279 | −7.674 | 2.232 |

| Age (covariate) | −0.063 (0.114) | −0.557 | 0.578 | −0.289 | 0.162 |

| Work experience in years (covariate) | 00.081 (0.119) | 0.675 | 0.500 | −0.156 | 0.318 |

| Baseline Resilience (covariate) | 0.255 (0.056) | 4.564 | <0.001 | 0.144 | 0.366 |

| Model Summary R = 0.434 R2 = 0.188 F = 5.766 p < 0.001 | |||||

| Total Effect of X on Y Effect (SE) = −0.222 (0.217) t = −1.022 p = 0.308 LLCI = −0.652 ULCI = 0.208 | |||||

| Direct Effect of X on Y Effect (SE) = 0.053 (0.215) t = 0.248 p = 0.804 LLCI = −0.372 ULCI = 0.479 | |||||

| Indirect effect of X on Y Effect (SE) = −0.275 (0.100) LLCI = −0.487 ULCI = −0.097 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gil-Almagro, F.; García-Hedrera, F.J.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. From Anxiety to Hardiness: The Role of Self-Efficacy in Spanish CCU Nurses in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina 2024, 60, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60020215

Gil-Almagro F, García-Hedrera FJ, Carmona-Monge FJ, Peñacoba-Puente C. From Anxiety to Hardiness: The Role of Self-Efficacy in Spanish CCU Nurses in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina. 2024; 60(2):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60020215

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil-Almagro, Fernanda, Fernando José García-Hedrera, Francisco Javier Carmona-Monge, and Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente. 2024. "From Anxiety to Hardiness: The Role of Self-Efficacy in Spanish CCU Nurses in the COVID-19 Pandemic" Medicina 60, no. 2: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60020215