Evaluation of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Males and Urinary Incontinence in Females in Primary Health Care in Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

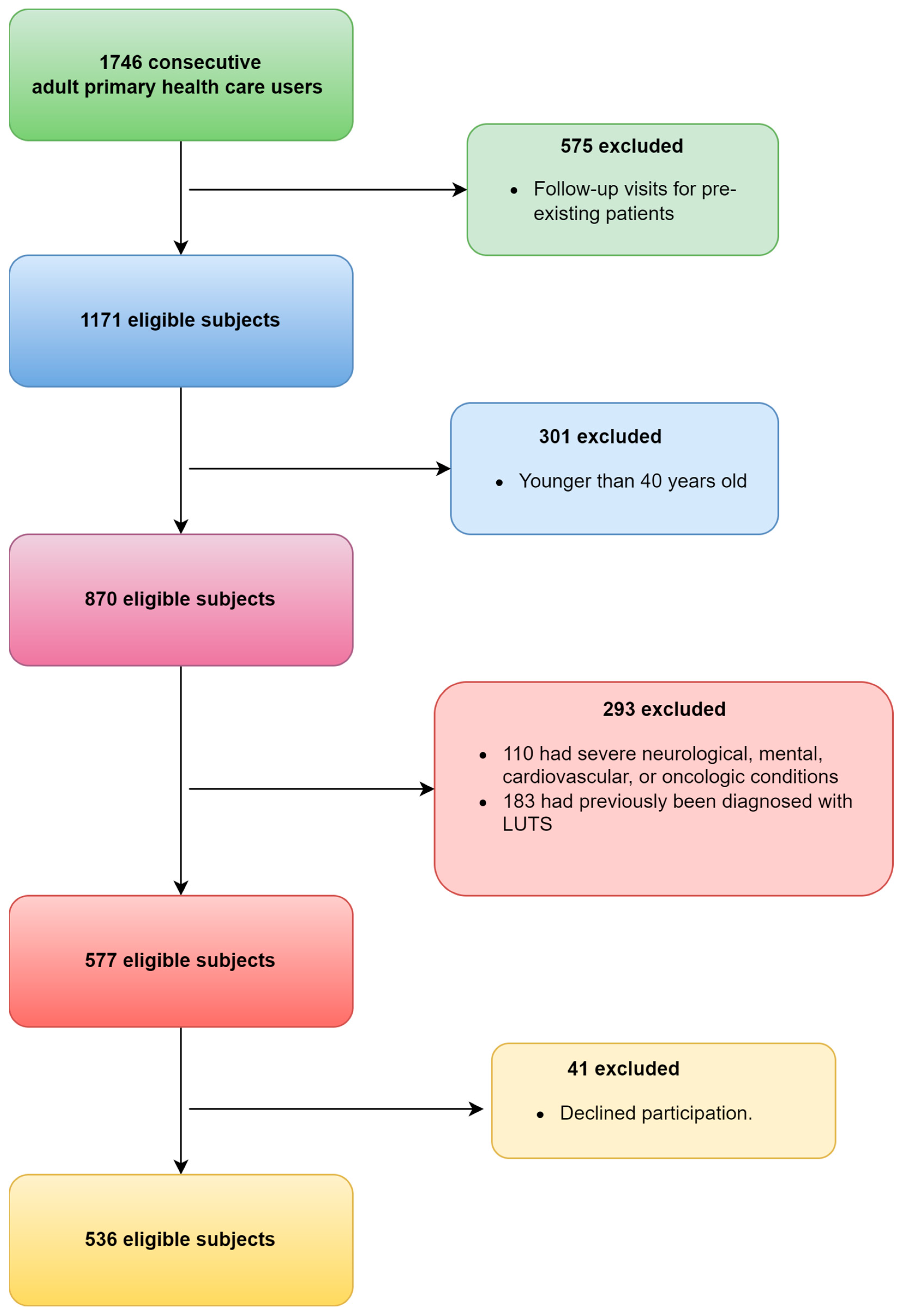

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Study Tools and Outcomes

2.3.1. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)

2.3.2. International Index of Erectile Function

2.3.3. International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF)

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. LUTS in Male Population

3.3. Erectile Dysfunction in Male Population

3.4. LUTS in Female Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gajewski, J.B.; Drake, M.J. Neurological lower urinary tract dysfunction essential terminology. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, S25–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, B.W.; Summers, S.; Patel, D.; Garcia, M.; Bandeko, C. A Practical Approach for Primary Care Practitioners to Evaluate and Manage Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Fed. Pract. 2021, 38, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chan, C.K.; Yee, S.; Deng, Y.; Bai, Y.; Chan, S.C.; Tin, M.S.; Liu, X.; Lok, V.; Zhang, L.; et al. Global burden and temporal trends of lower urinary tract symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2023, 26, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Sexton, C.C.; Kopp, Z.S.; Ebel-Bitoun, C.; Milsom, I.; Chapple, C. The impact of overactive bladder on mental health, work productivity and health-related quality of life in the UK and Sweden: Results from EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Lam, C.L.K.; Chin, W.Y. Mental health of Chinese primary care patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Psychol. Health Med. 2016, 21, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.H.; Lam, C.L.K.K.; Chin, W.-Y.Y. The health-related quality of life of Chinese patients with lower urinary tract symptoms in primary care. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, K.S.; Wein, A.J.; Tubaro, A.; Sexton, C.C.; Thompson, C.L.; Kopp, Z.S.; Aiyer, L.P. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: Evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009, 103, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Huang, J.; Chau, P.H.; Wan, E.Y.F. Health-related quality of life among Chinese primary care patients with different lower urinary tract symptoms: A latent class analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.A.; Nettleton, J.; Blain, C.; Dalton, C.; Farhan, B.; Fernandes, A.; Georgopoulos, P.; Klepsch, S.; Lavelle, J.; Martinelli, E.; et al. Assessment of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms where an undiagnosed neurological disease is suspected: A report from an International Continence Society consensus working group. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2020, 39, 2535–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qasrawi, H.; Tabouni, M.; Almansour, S.W.; Ghannam, M.; Abdalhaq, A.; Abushamma, F.; Koni, A.A.; Zyoud, S.H. An evaluation of lower urinary tract symptoms in diabetic patients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Urol. 2022, 22, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVary, K.T.; Roehrborn, C.G.; Avins, A.L.; Barry, M.J.; Bruskewitz, R.C.; Donnell, R.F.; Foster, H.E.; Gonzalez, C.M., Jr.; Kaplan, S.A.; Penson, D.F.; et al. Update on AUA guideline on the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Urol. 2011, 185, 1793–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacci, M.; Sakalis, V.I.; Karavitakis, M.; Cornu, J.N.; Gratzke, C.; Herrmann, T.R.W.; Kyriazis, I.; Malde, S.; Mamoulakis, C.; Rieken, M.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Male Urinary Incontinence. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesonen, J.S.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Cartwright, R.; Aoki, Y.; Agarwal, A.; Mangera, A.; Markland, A.D.; Tsui, J.F.; Santti, H.; Griebling, T.L.; et al. The impact of nocturia on falls and fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Urol. 2020, 203, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.A.; Haren, M.T.; Marshall, V.R.; Lange, K.; Wittert, G.A.; Members of the Florey Adelaide Male Ageing Study. Prevalence and factors associated with uncomplicated storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms in community-dwelling Australian men. World J. Urol. 2011, 29, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Eryuzlu, L.N.; Cartwright, R.; Thorlund, K.; Tammela, T.L.; Guyatt, G.H.; Auvinen, A.; Tikkinen, K.A. What is the most bothersome lower urinary tract symptom? Individual- and population-level perspectives for both men and women. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmoteleb, H.; Jefferies, E.R.; Drake, M.J. Assessment and management of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Int. J. Surg. 2016, 25, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Fukuta, F.; Takayanagi, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Tanaka, T.; Masumori, N. Which Happens Earlier, Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms or Erectile Dysfunction? Sex. Med. 2021, 9, 100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.M.; Vaughan, C.P.; Goode, P.S.; Redden, D.T.; Burgio, K.L.; Richter, H.E.; Markland, A.D. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Obset. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offermans, M.P.; Du Moulin, M.F.; Hamers, J.P.; Dassen, T.; Halfens, R.J. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated risk factors in nursing home residents: A systematic review. Neurol. Urodyn. 2009, 28, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anger, J.T.; Saigal, C.S.; Litwin, M.S.; Urologic Diseases of America Project. The prevalence of urinary incontinence among community dwelling adult women: Results from the National Health and nutrition examination survey. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minassian, V.A.; Yan, X.; Lichtenfeld, M.J.; Sun, H.; Stewart, W.F. The iceberg of health care utilization in women with urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2012, 23, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.S.; McGhan, W.F.; Chokroverty, S. Comorbidities associated with overactive bladder. Am. J. Manag. Care 2000, 6, S574–S579. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T.H.; Hu, T.W.; Bentkover, J.; LeBlanc, K.; Stewart, W.; Corey, R.; Zhou, Z.; Hunt, T. Health-related consequences of overactive bladder. Am. J. Manag. Care 2002, 8, S598–S607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gibson, W.; Hunter, K.F.; Camicioli, R.; Booth, J.; Skelton, D.A.; Dumoulin, C.; Paul, L.; Wagg, A. The association between lower urinary tract symptoms and falls: Forming a theoretical model for a research agenda. Neurol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, S.; Kawahara, T.; Tsutsumi, S.; Ito, H.; Makiyama, K.; Uemura, H. Lower urinary tract symptoms are elevated with depression in Japanese women. Low. Urin. Tract Symptoms 2023, 15, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, W.; Harari, D.; Husk, J.; Lowe, D.; Wagg, A. A national benchmark for the initial assessment of men with LUTS: Data from the 2010 Royal College of Physicians National Audit of Continence Care. World J. Urol. 2016, 34, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, M.J.; Worthington, J.; Frost, J.; Sanderson, E.; Cochrane, M.; Cotterill, N.; Fader, M.; McGeagh, L.; Hashim, H.; Macaulay, M.; et al. Treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men in primary care using a conservative intervention: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2023, 383, e075219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basra, R.K.; Cortes, E.; Khullar, V.; Kelleher, C. A comparison study of two lower urinary tract symptoms screening tools in clinical practice: The B-SAQ and OAB-V8 questionnaires. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 32, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravas, S.; Gacci, M.; Gratzke, C.; Herrmann, T.R.W.; Karavitakis, M.; Kyriazis, I.; Malde, S.; Mamoulakis, C.; Rieken, M.; Sakalis, V.I.; et al. Summary Paper on the 2023 European Association of Urology Guidelines on the Management of Non-Neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, A.K.; Arlandis, S.; Bø, K.; Cobussen-Boekhorst, H.; Costantini, E.; de Heide, M.; Farag, F.; Groen, J.; Karavitakis, M.; Lapitan, M.C.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Female Non-neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Part 1: Diagnostics, Overactive Bladder, Stress Urinary Incontinence, and Mixed Urinary Incontinence. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionis, C.; Vlachonikolis, L.; Bathianaki, M.; Daskalopoulos, G.; Anifantaki, S.; Cranidis, A. Urinary incontinence, the hidden health problem of Cretan women: Report from a primary care survey in Greece. Women Health 2000, 31, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liapis, A.; Bakas, P.; Liapi, S.; Sioutis, D.; Creatsas, G. Epidemiology of female urinary incontinence in the Greek population: EURIG study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2010, 21, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anifantaki, S.; Filiz, T.M.; Alegakis, A.; Topsever, P.; Markaki, A.; Cinar, N.D.; Sofras, F.; Lionis, C. Does urinary incontinence affect quality of life of Greek women less severely? A cross-sectional study in two Mediterranean settings. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.J.; Fowler, F.J.; O’Leary, M.P., Jr.; Bruskewitz, R.C.; Holtgrewe, H.L.; Mebust, W.K.; Cockett, A.T. The measurement committee of the American urological association, the American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Urol. 1992, 148, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, P.; Chapple, C.; Khoury, S.; Roehrborn, C.; de la Rosette, J.; International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Diseases. Evaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older men. J. Urol. 2013, 189, S93–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaefstathiou, E.; Moysidis, K.; Sarafis, P.; Ioannidis, E.; Hatzimouratidis, K. The impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in both male and female patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, R.C.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Smith, M.D.; Lipsky, J.; Peña, B.M. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 1999, 11, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzimouratidis, K.; Tsimtsiou, Z.; Karantana, A.; Hatzichristou, D. Cultural and linguistic validation of International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) in Greek language. Hell. Urol. 2001, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, K.; Donovan, J.; Peters, T.J.; Shaw, C.; Gotoh, M.; Abrams, P. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2004, 23, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, S.; Grigoriadis, T.; Kyriakidou, N.; Giannoulis, G.; Antsaklis, A. The validation of international consultation on incontinence questionnaires in the Greek language. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2012, 31, 1141–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A.Y.; Xu, X. Prevalence, Burden, and Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Men Aged 50 and Older: A Systematic Review of the Literature. SAGE Open Nurs. 2018, 4, 2377960818811773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, C.; Castro-Diaz, D.; Chuang, Y.C.; Lee, K.S.; Liao, L.; Liu, S.P.; Wang, J.; Yoo, T.K.; Chu, R.; Sumarsono, B. Prevalence of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in China, Taiwan, and South Korea: Results from a Cross-Sectional, Population-Based Study. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: Results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009, 104, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.E.; Milsom, I.; Kopp, Z.; Abrams, P.; Artibani, W.; Herschorn, S. Prevalence, severity, and symptom bother of lower urinary tract symptoms among men in the EPIC study: Impact of overactive bladder. Eur. Urol. 2009, 56, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, R.; Gomes, C.M.; Averbeck, M.A.; Koyama, M. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in Brazil: Results from the epidemiology of LUTS (Brazil LUTS) study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2017, 37, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isa, N.M.M.; Aziz, A.F.A. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Prevalence and Factors Associated with Help-Seeking in Male Primary Care Attendees. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2020, 41, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, U.C.; Wun, Y.T.; Luo, T.C.; Pang, S.M. In a free healthcare system, why do men not consult for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)? Asia Pac. Fam. Med. 2011, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, A.; Kirana, P.S.; Chiu, G.; Link, C.; Tsiouprou, M.; Hatzichristou, D. Gender and age differences in the perception of bother and health care seeking for lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from the hospitalised and outpatients’ profile and expectations study. Eur. Urol. 2009, 56, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.; McGrother, C.W.; Harrison, S.C.; Assassa, P.R.; Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Team. Lower urinary tract symptoms and related help-seeking behaviour in South Asian men living in the UK. BJU Int. 2006, 98, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, C.; Tansey, R.; Jackson, C.; Hyde, C.; Allan, R. Barriers to help seeking in people with urinary symptoms. Fam. Pract. 2001, 18, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, A.; de Nunzio, C.; Tubaro, A. What determines whether a patient with LUTS seeks treatment?: ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2012, 31, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malde, S.; Umbach, R.; Wheeler, J.R.; Lytvyn, L.; Cornu, J.N.; Gacci, M.; Gratzke, C.; Herrmann, T.R.W.; Mamoulakis, C.; Rieken, M.; et al. A Systematic Review of Patients’ Values, Preferences, and Expectations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters, R.; Wensing, M.; van Weel, C.; van der Wilt, G.J.; Grol, R.P. Lower urinary tract symptoms: Social influence is more important than symptoms in seeking medical care. BJU Int. 2002, 90, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, H.A.; van Wijnhoven, R.; Teunissen, T.A.; Harmsen, S.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L. Why do men suffering from LUTS seek primary medical care? A qualitative study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horrocks, S.; Somerset, M.; Stoddart, H.; Peters, T.J. What prevents older people from seeking treatment for urinary incontinence?: A qualitative exploration of barriers to the use of community continence services. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 689–696. [Google Scholar]

- Kupelian, V.; Wei, J.T.; O’Leary, M.P.; Kusek, J.W.; Litman, H.J.; Link, C.L.; McKinlay, J.B.; BACH Survery Investigators. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: The Boston area community health (BACH) survey. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derimachkovski, G.; Yotovski, V.; Mladenov, V.; Ianev, K.; Mladenov, D. Men with LUTS and diabetes mellitus. Acta Chir. Iugosl. 2014, 61, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Kaplan, S.A.; Chapple, C.R.; Sexton, C.C.; Kopp, Z.S.; Bush, E.N.; Aiyer, L.P. Risk factors and comorbid conditions associated with lower urinary tract symptoms: EpiLUTS. BJU Inter. 2009, 103, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, H.J.; Steers, W.D.; Wei, J.T.; Kupelian, V.; Link, C.L.; McKinlay, J.B.; Boston Area Community Health Survey Investigators. Relationship of lifestyle and clinical factors to lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from Boston Area Community Health survey. Urology 2007, 70, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, C.P.; Johnson, T.M.; Goode, P.S.; Redden, D.T.; Burgio, K.L.; Markland, A.D. Vitamin D and lower urinary tract symptoms among US men: Results from the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Urology 2011, 78, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Zhou, Z.; Bhattacharyya, S.K.; Thompson, C.L.; Dhawan, R.; Versi, E. The prevalence of nocturia and its effect on health-related quality of life and sleep in a community sample in the USA. BJU Int. 2003, 92, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.K.; Garcia, L.A.; Rosen, R. Lower urinary tract symptoms and male sexual dysfunction in Asia: A survey of ageing men from five Asian countries. BJU Int. 2005, 96, 1339–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vartolomei, L.; Cotruș, A.; Tătaru, S.O.; Vartolomei, M.D.; Man, A.; Ferro, M.; Stanciu, C.; Sin, A.I.; Shariat, S.F. Lower urinary tract symptoms are associated with clinically relevant depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Aging Male 2022, 25, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, R.; Altwein, J.; Boyle, P. Lower urinary tract symptoms and male sexual dysfunction: The multinational survey of the aging male (MSAM-7). Eur. Urol. 2003, 44, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Fujimura, T.; Nagata, M. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual dysfunction assessed using the core lower urinary tract symptom score and International Index of Erectile Function-5 questionnaires. Aging Male 2012, 15, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponholzer, A.; Temml, C.; Obermayr, R. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction. Urology 2004, 64, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fwu, C.W.; Kirkali, Z.; McVary, K.T. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations of sexual function with lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Urol. 2015, 193, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, A.; Rantell, A.; Anding, R.; Kirschner-Hermanns, R.; Cardozo, L. How does lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) affect sexual function in men and women? ICI-RS 2015-Part 2. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2017, 36, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandra, R.; Aleksandra, S.; Iwona, R. Erectile Dysfunction in Relation to Metabolic Disorders and the Concentration of Sex Hormones in Aging Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Sanchez, B.; Cendejas-Gomez, J.; Rivera-Ramirez, J.A.; Herrera-Caceres, J.O.; Olvera-Posada, D.; Villeda-Sandoval, C.I.; Castillejos-Molina, R.A.; Feria-Bernal, G.; Garcia-Mora, A.; Rodriguez-Covarrubias, F. The correlation between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and erectile dysfunction (ED): Results from a survey in males from Mexico City (MexiLUTS). World J. Urol. 2016, 34, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafi, F.A.; Jenkins, L.; Albersen, M.; Corona, G.; Isidori, A.M.; Goldfarb, S.; Maggi, M.; Nelson, C.J.; Parish, S.; Salonia, A.; et al. Erectile dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadzil, M.A.; Sidi, H.; Ismail, Z.; Hassan, M.R.; Thuzar, K.; Midin, M.; Nik Jaafar, N.R.; Das, S. Socio-demographic and psychosocial correlates of erectile dysfunction among hypertensive patients. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, S23–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Guo, R.; Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Dong, P.; Li, Y. Prevalence and Characteristics of Erectile Dysfunction in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 812974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akgül, M.; Yazıcı, C.; Doğan, Ç.; Özcan, R.; Şahin, M.F. Erectile dysfunction iceberg in an urology outpatient clinic: How can we encourage our patients to be more forthcoming? Andrologia 2021, 53, e14152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nihira, M.A.; Henderson, N. Epidemiology of urinary incontinence in women. Curr. Womens Health Rep. 2003, 3, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patel, U.J.; Godecker, A.L.; Giles, D.L.; Brown, H.W. Updated prevalence of urinary incontinence in women: 2015–2018 national population-based survey data. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 28, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose, S.M.; Gangnon, R.E.; Chewning, B.; Wald, A. Increasing Discussion Rates of Incontinence in Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruto, M.A.; D’Elia, C.; Aloisi, A.; Fabrello, M.; Artibani, W. Prevalence, incidence and obstetric factors’ impact on female urinary incontinence in Europe: A systematic review. Urol. Int. 2013, 90, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Annappa, M.; Quigley, A.; Dracocardos, D.; Bondili, A.; Mallen, C. Prevalence of female urinary incontinence and its impact on quality of life in a cluster population in the United Kingdom (UK): A community survey. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2015, 16, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.J.; Feinstein, L.; Ward, J.B.; Kirkali, Z.; Martinez-Miller, E.E.; Matlaga, B.R.; Kobashi, K.C. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among a nationally representative sample of women, 2005–2016: Findings from the urologic diseases in America project. J. Urol. 2021, 205, 1718–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, Y.; Kenton, K.; Cao, G.; Luke, A.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Kramer, H.; Brubaker, L. Urinary incontinence prevalence: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Urol. 2008, 179, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenskaia, K.; Haidvogel, K.; Heidinger, C.; Doerfler, D.; Umek, W.; Hanzal, E. The greatest taboo: Urinary incontinence as a source of shame and embarrassment. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2011, 123, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Berardesca, E.; Maibach, H.I. Psychosocial and societal burden of incontinence in the aged population: A review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2008, 277, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzol, D.; Demurtas, J.; Celotto, S.; Maggi, S.; Smith, L.; Angiolelli, G.; Trott, M.; Yang, L.; Veronese, N. Urinary incontinence and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, J.; Frost, J.; Lane, J.A.; Robles, L.A.; Rees, J.; Taylor, G.; Drake, M.J.; Ridd, M. Effective management of male lower urinary tract symptoms in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, 388–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bello, F.; Pezone, G.; Muzii, B.; Cilio, S.; Ruvolo, C.C.; Scandurra, C.; Mocini, E.; Creta, M.; Morra, S.; Bochicchio, V.; et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms in young-middle aged males with a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2024, 43, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markland, A.; Bavendam, T.; Cain, C.; Neill Epperson, C.; Fitzgerald, C.M.; Yvette LaCoursiere, D.; Shoham, D.A.; Smith, A.L.; Sutcliffe, S.; Rudser, K.; et al. Occupational groups and lower urinary tract symptoms: A cross-sectional analysis of women in the Boston Area Community Health Study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2024, 43, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peleg, L.C.; Rabinovitch, D.; Lavie, Y.; Rabbie, D.M.; Horowitz, I.; Fruchter, E.; Gruenwald, I. Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction (PSSD): Biological Plausibility, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Presumed Risk Factors. Sex. Med. Rev. 2022, 10, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semczuk-Kaczmarek, K.; Płatek, A.E.; Szymański, F.M. Co-treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and cardiovascular disease—Where do we stand? Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2020, 73, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 ± 13 |

| Age group 40–50 years | 125 (23%) |

| Age group 51–64 years | 150 (28%) |

| Age group ≥65 years | 261 (49%) |

| Gender, male (%) | 206 (38%) |

| Education level (n = 512) | |

| Primary level | 131 (25%) |

| Secondary level | 224 (44%) |

| Higher level | 157 (31%) |

| Occupational status | 82 (9%) |

| Retired | 257 (48%) |

| Sedentary work | 161 (30%) |

| Manual work | 118 (22%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Arterial hypertension | 255 (48%) |

| COPD/asthma | 46 (9%) |

| Diabetes type 2 | 93 (17%) |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 32 (6%) |

| Depression (on medication) | 41 (8%) |

| Rheumatologic disease | 42 (8%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 184 (34%) |

| Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| Male population | |

| IPSS score (range 0–35) (n = 206) | 3 (0, 9) |

| Non-Mild (IPSS 0–7 points) | 139 (68%) |

| Moderate (IPSS 8–19 points) | 64 (31%) |

| Severe (IPSS 20–35 points) | 3 (1%) |

| IPSS quality of life score (range 0–6) | 2 (0, 3) |

| Poor quality of life (score ≥3) | 46 (25%) |

| IIEF-5 (range: 0–25 points) (n = 199) | 10 (4, 20) |

| Normal (IIEF-5 22–25 points) | 32 (16%) |

| Mild (IIEF-5 17–21 points) | 42 (21%) |

| Mild to moderate (IIEF 12–16 points) | 22 (11%) |

| Moderate to severe (IIEF 8–11 points) | 22 (11%) |

| Severe (IIEF-5 0–7 points) | 81 (41%) |

| Female population | |

| ICIQ-UI-SF score (range 0–21) | 3 (0, 8) |

| ICIQ 0 | 142 (41.7%) |

| ICIQ slight (1–5), | 75 (22%) |

| ICIQ moderate (6–12), | 100 (29%) |

| ICIQ severe (13–18) | 24 (7%) |

| ICIQ very severe (19–21) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Quality of life due to urinary symptoms total score | 1 (0, 3) |

| Poor quality of life (score ≥3) | 106 (31%) |

| Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-LUTS | LUTS | p-Value | |

| None–mild IPSS | Moderate–severe IPSS | ||

| n = 139 | n = 67 | ||

| Age (years) | 58 ± 12 | 70 ± 11 | 0.001 |

| Age groups | <0.001 | ||

| Age group 40–50 years | 52 (37%) | 4 (6%) | |

| Age group 51–64 years | 42 (30%) | 11 (16%) | |

| Age group ≥65 years | 45 (33%) | 52 (78%) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||

| Primary level | 17 (13%) | 23 (35%) | |

| Secondary level | 64 (48%) | 28 (43%) | |

| Higher level | 52 (39%) | 14 (22%) | |

| Occupational status | <0.001 | ||

| Retired | 37 (27%) | 50 (75%) | |

| Sedentary work | 38 (27%) | 7 (10%) | |

| Manual work | 64 (46%) | 10 (15%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 52 (37%) | 43 (64%) | <0.001 |

| COPD/asthma | 12 (9%) | 9 (13%) | 0.286 |

| Diabetes type 2 | 13 (9%) | 25 (37%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 7 (5%) | 9 (13%) | 0.035 |

| Depression (on medication) | 3 (2%) | 5 (8%) | 0.065 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 0.966 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 44 (32%) | 35 (52%) | 0.004 |

| Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ED | ED | p-Value | |

| None–mild IIEF-5 | Moderate–severe IIEF-5 | ||

| n = 74 | n = 125 | ||

| Age (years) | 59 ± 9 | 63 ± 15 | 0.001 |

| Age groups | <0.001 | ||

| Age group 40–50 years | 9 (12%) | 47 (38%) | |

| Age group 51–64 years | 45 (61%) | 8 (6%) | |

| Age group ≥65 years | 20 (27%) | 71 (56%) | |

| Education level | 0.028 | ||

| Primary level | 11 (15%) | 28 (23%) | |

| Secondary level | 43 (58%) | 47 (38.5%) | |

| Higher level | 20 (27%) | 47 (38.5%) | |

| Occupational status | <0.001 | ||

| Retired | 16 (22%) | 65 (52%) | |

| Sedentary work | 21 (28%) | 23 (18%) | |

| Manual work | 37 (50%) | 37 (30%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 28 (38%) | 60 (48%) | 0.163 |

| COPD/asthma | 8 (10%) | 12 (10%) | 0.784 |

| Diabetes type 2 | 12 (16%) | 25 (20%) | 0.507 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 3 (4%) | 12 (10%) | 0.152 |

| Depression (on medication) | 2 (3%) | 6 (5%) | 0.467 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 3 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 0.285 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 26 (35%) | 49 (39%) | 0.567 |

| Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-LUTS | LUTS | p-Value | |

| None–slight ICIQ-UI-SF | Moderate–severe ICIQ-UI-SF | ||

| n = 217 | n = 125 | ||

| Age (years) | 62 ± 13 | 68 ± 13 | 0.001 |

| Age groups | <0.001 | ||

| Age group 40–50 years | 49 (23%) | 22 (18%) | |

| Age group 51–64 years | 79 (36%) | 24 (19%) | |

| Age group ≥65 years | 89 (41%) | 79 (63%) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||

| Primary level | 48 (22%) | 50 (40%) | |

| Secondary level | 95 (44%) | 51 (41%) | |

| Higher level | 74 (34%) | 24 (19%) | |

| Occupational status | 0.002 | ||

| Retired | 95 (44%) | 79 (63%) | |

| Sedentary work | 86 (40%) | 33 (27%) | |

| Manual work | 36 (16%) | 13 (10%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 90 (42%) | 77 (62%) | <0.001 |

| COPD/asthma | 19 (9%) | 8 (6%) | 0.837 |

| Diabetes type 2 | 20 (9%) | 36 (29%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 10 (5%) | 7 (6%) | 0.684 |

| Depression (on medication) | 19 (9%) | 14 (11%) | 0.461 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 21 (10%) | 15 (12%) | 0.500 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 57 (26%) | 51 (41%) | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gkatzoudi, C.; Bouloukaki, I.; Mamoulakis, C.; Lionis, C.; Tsiligianni, I. Evaluation of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Males and Urinary Incontinence in Females in Primary Health Care in Greece. Medicina 2024, 60, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60030389

Gkatzoudi C, Bouloukaki I, Mamoulakis C, Lionis C, Tsiligianni I. Evaluation of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Males and Urinary Incontinence in Females in Primary Health Care in Greece. Medicina. 2024; 60(3):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60030389

Chicago/Turabian StyleGkatzoudi, Claire, Izolde Bouloukaki, Charalampos Mamoulakis, Christos Lionis, and Ioanna Tsiligianni. 2024. "Evaluation of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Males and Urinary Incontinence in Females in Primary Health Care in Greece" Medicina 60, no. 3: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60030389