Behçet’s Disease, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment Approaches: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. What Is the Typical Presentation of Behçet’s Disease in Adults?

3.2. What Is the Epidemiology of Behçet’s Disease?

3.3. What Causes Behçet’s Disease?

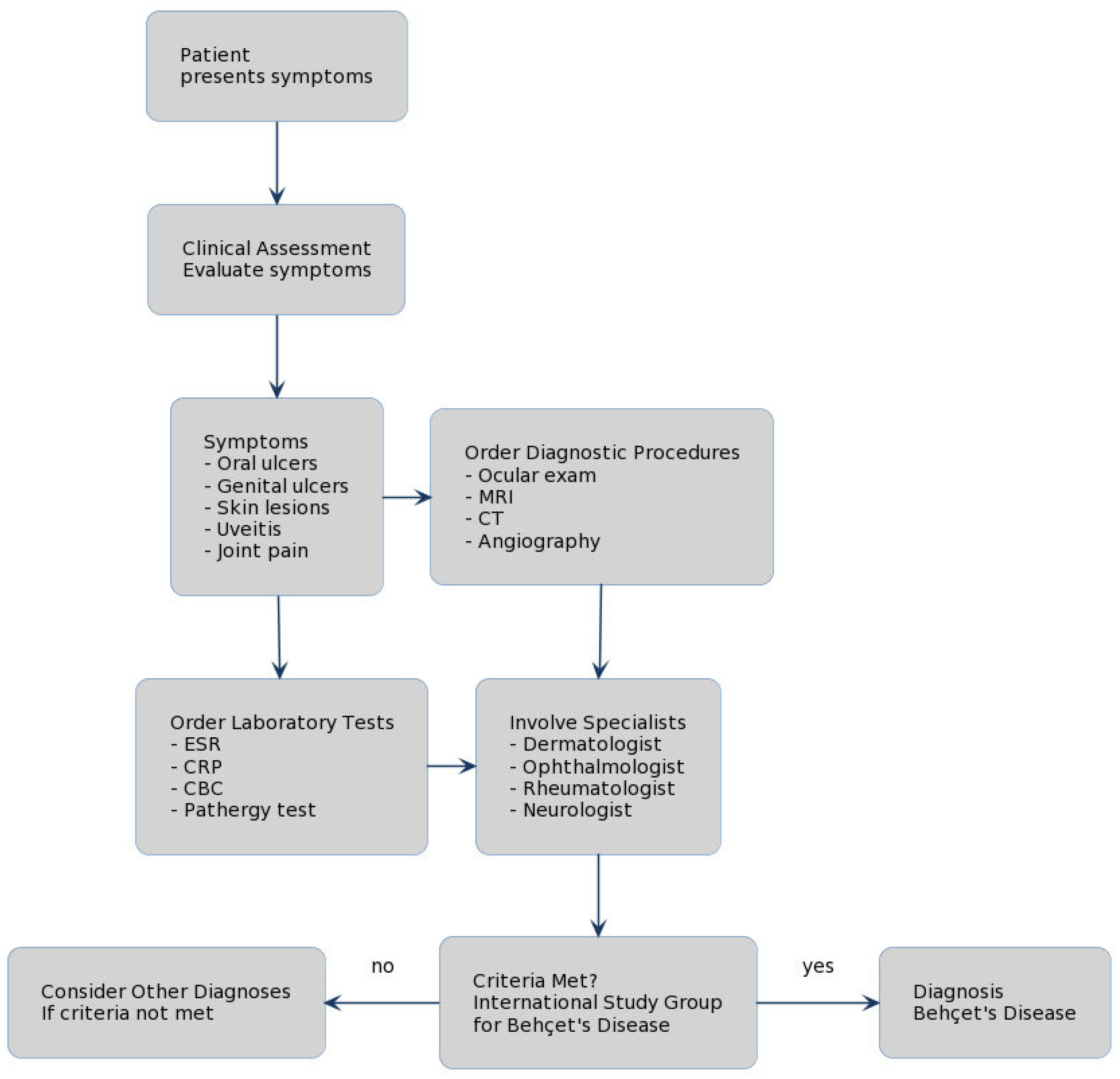

3.4. What Diagnostic Tests Are Recommended for Behçet’s Disease?

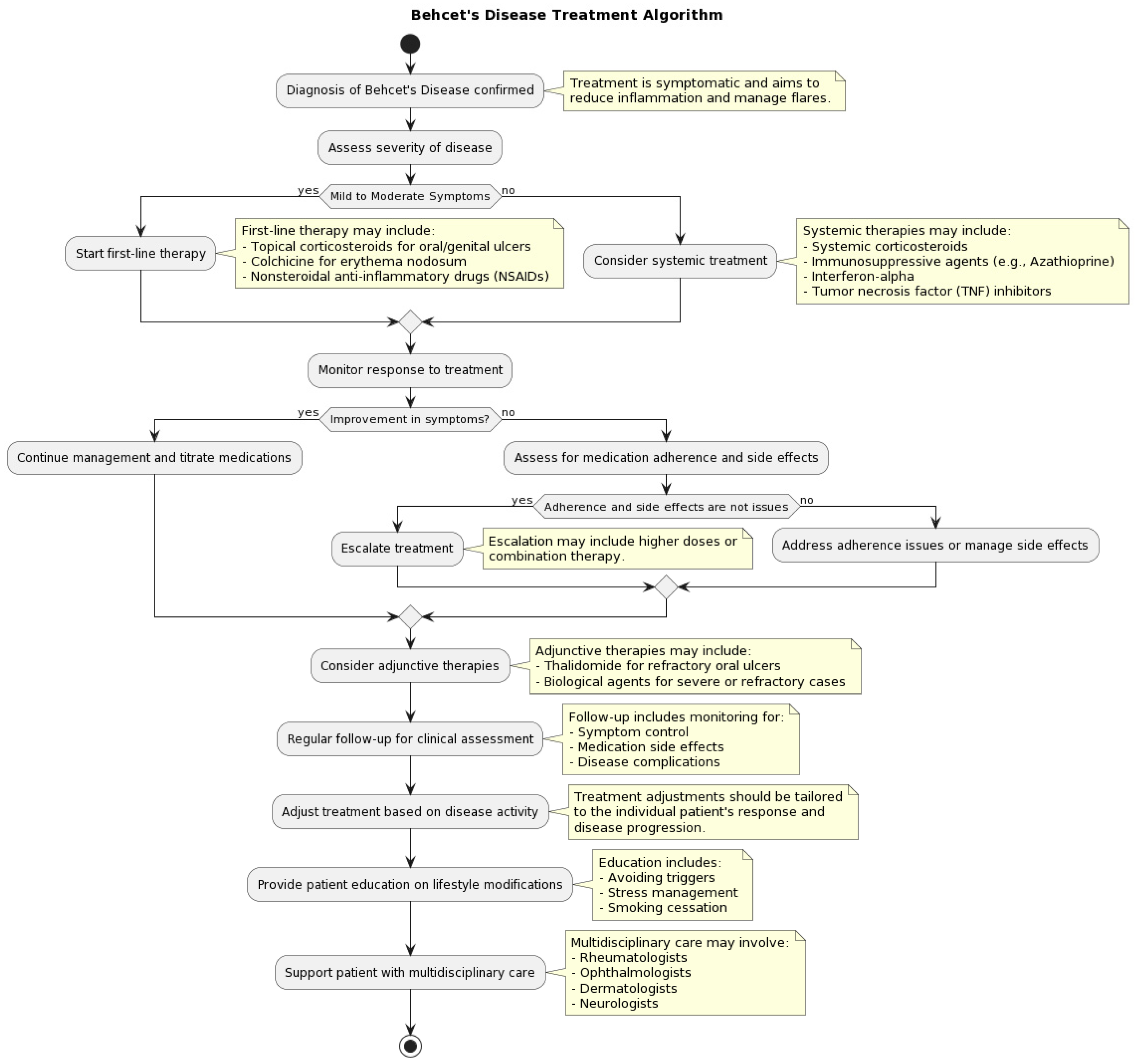

3.5. How Is Behçet’s Disease Managed and Treated?

3.6. What Is the Prognosis of Behçet’s Disease?

3.7. What Are the Potential Complications of Behçet’s Disease?

3.8. What Lifestyle Modifications Can Help Manage Behçet’s Disease?

3.9. What Is the Impact of Behçet’s Disease on Mental Health?

3.10. Can Behçet’s Disease Affect Pregnancy and Fertility?

3.11. While a Multidisciplinary Approach Is Required for Behçet’s Disease?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions/Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Behçet, H. Über rezidivierende, aphthose, durch ein virus verursachte Geschwüre am Mund, am Auge und an den Genitalien. Dermatol. Wochenschr. 1937, 105, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Behçet, H. Considerations sur les lesions aphteuses de la bouche et des parties genitals, ainsi que sur les manifestations oculaires d’origine probablement virutique et observations concernant leur foyer d’infection. Bull. Soc. Fr. Dermatol. Syphiligr. 1938, 45, 420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Sakane, T.; Takeno, M.; Suzuki, N.; Inaba, G. Behçet’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 1284–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verity, D.H.; Marr, J.E.; Ohno, S.; Wallace, G.R.; Stanford, M.R. Behçet’s disease, the silk road and HLA-B51: Historical and geographical perspectives. Tissue Antigens 1999, 54, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour, S.; Nouri, M.; Sakhinia, E.; Samadi, N.; Roshanravan, N.; Ghavami, A.; Khabbazi, A. Epigenetic alterations in chronic disease focusing on Behçet disease: Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulaber, A.; Tugal-Tutkun, I.; Sibel, P.; Akman-Demir, G.; Kaneko, F.; Gul, A.; Saruhan-Direskeneli, G. Pro-inflammatory cellular immune response in Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol. Int. 2007, 27, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodis, G.; Toth, V.; Schwarting, A. Role of Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) in Autoimmune Diseases. Rheumatol. Ther. 2018, 5, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davatchi, F.; Champs-Davatchi, C.; Shams, H.; Shahram, F.; Nadji, A.; Akhlaghi, M.; Faezi, T.; Ghodsi, Z.; Abdollahi, B.S.; Ashofteh, F.; et al. Behçet’s disease: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 13, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 1990, 335, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, B.; Sbai, A.; Du-Boutin, L.T.; Duhaut, P.; Dormont, D.; Piette, J.C. Neurological manifestations of Behçet’s disease. Rev. Neurol. 2002, 158, 926–933. [Google Scholar]

- Hatemi, G.; Christensen, R.; Bang, D.; Bodaghi, B.; Celik, A.F.; Fortune, F.; Gaudric, J.; Gul, A.; Kötter, I.; Leccese, P.; et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet’s syndrome. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018, 77, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evereklioglu, C. Current concepts in the etiology and treatment of Behçets disease. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2005, 50, 297–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadoun, D. Behçet’s disease: The French recommendations. Rev. Med. Interne 2020, 41, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, H.; Pazarli, H.; Barnes, C.G.; Tuzun, Y.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Silman, A.; Serdaroğlu, S.; Oğuz, V.; Yurdakul, S.; Lovatt, G.E.; et al. A controlled trial of azathioprine in Behçet’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibaz-Oner, F.; Sawalha, A.H.; Direskeneli, H. Management of Behçet’s disease. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comarmond, C.; Wechsler, B.; Bodaghi, B.; Cacoub, P.; Saadoun, D. Biotherapies in Behçet’s disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014, 13, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibaz-Oner, F.; Direskeneli, H. Advances in treating Behcet’s Disease. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherrer, M.A.R.; Rocha, V.B.; Garcia, L.C. Behçet’s disease: Review with emphasis on dermatological aspects. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.K.; Dao, H., Jr. Off-label dermatologic uses of IL-17 inhibitors. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2022, 33, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Houwen, T.B.; van Hagen, P.M.; van Laar, J.A.M. Immunopathogenesis of Behçet’s disease and treatment modalities. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2022, 52, 151956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; He, F.; Shi, Y. Behcet’s disease seen in China: Analysis of 334 cases. Rheumatol. Int. 2013, 33, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arida, A.; Saadoun, D.; Sfikakis, P.P. IL-6 blockade for Behçet’s disease: Review on 31 anti-TNF naive and 45 anti-TNF experienced patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2022, 40, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filleron, A.; Tran, T.A.; Hubert, A.; Letierce, A.; Churlaud, G.; Koné-Paut, I.; Saadoun, D.; Cezar, R.; Corbeau, P.; Rosenzwajg, M. Regulatory T cell/Th17 balance in the pathogenesis of paediatric Behçet disease. Rheumatology 2021, 61, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, J.S.; Ishaq, M.; Ahmed, K. Genetics and Epigenetics Mechanism in the Pathogenesis of Behçet’s Disease. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2019, 15, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklamani, V.G.; Vaiopoulos, G.; Kaklamanis, P.G. Behçet’s disease. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 27, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.A.; Stephen, S.; Ashchyan, H.J.; James, W.D.; Micheletti, R.G.; Rosenbach, M. Neutrophilic dermatoses: Pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, S.; Balta, I.; Demirkol, S.; Ozturk, C.; Demir, M. Endothelial function and Behçet disease. Angiology 2014, 65, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazici, Y.; Yurdakul, S.; Yazici, H. Behçet’s syndrome. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2010, 12, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete, J.D.; Celis, R.; Noordenbos, T.; Moll, C.; Gómez-Puerta, J.A.; Pizcueta, P.; Palacin, A.; Tak, P.P.; Sanmartí, R.; Baeten, D. Distinct synovial immunopathology in Behçet disease and psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, R17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuelyan, Z.; Butt, E.; Parupudi, S. Gastrointestinal Behçet’s disease: Manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Dis. Mon. 2024, 70, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatemi, I.; Hatemi, G.; Çelik, A.F. Systemic vasculitis and the gut. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017, 29, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, D.P. Neurological complications of Behçet’s syndrome. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 2178–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, D.P. Neurological involvement by Behçet’s syndrome: Clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and outcome. Pract. Neurol. 2023, 23, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Bravo, A.; Parra Soto, C.; Bellosta Diago, E.; Cecilio Irazola, Á.; Santos-Lasaosa, S. Neurological manifestations of Behçet’s disease: Case report and literature review. Reumatol. Clin. 2019, 15, e36–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenière, C.; Blanc, C.; Devilliers, H.; Samson, M.; Delpont, B.; Bielefeld, P.; Besancenot, J.F.; Giroud, M.; Béjot, Y. Associated arterial and venous cerebral manifestations in Behçet’s disease. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 174, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, O.; Bolek, E.C. Management of Behcet’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2020, 59, iii108–iii117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpsoy, E.; Leccese, P.; Ergun, T. Editorial: Behçet’s Disease: Epidemiology, Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 794874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonitsis, N.G.; LaValley, M.P.; Mantero, J.C.; Altenburg, A.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Kotter, I.; Micheli, C.; Maldini, C.; Mahr, A.; Zouboulis, C.C. Gender-specific differences in Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease manifestations: An analysis of the German registry and meta-analysis of data from the literature. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, A.; Inanç, M.; Ocal, L.; Aral, O.; Koniçe, M. Familial aggregation of Behçet’s disease in Turkey. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000, 59, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennani, N.; Atouf, O.; Benseffaj, N.; Brick, C.; Essakalli, M. Polymorphisme HLA et maladie de Behçet dans la population marocaine [HLA polymorphism and Behçet’s disease in Moroccan population]. Pathol. Biol. 2009, 57, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, K. Th17 cells in Behçet’s disease: A new immunoregulatory axis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2011, 29, S71–S76. [Google Scholar]

- International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ITR-ICBD); Davatchi, F.; Assaad-Khalil, S.; Calamia, K.T.; Crook, J.E.; Sadeghi-Abdollahi, B.; Schirmer, M.; Tzellos, T.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Akhlagi, M.; et al. The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD): A collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, H.; Fresko, I.; Yurdakul, S. Behçet’s syndrome: Disease manifestations, management, and advances in treatment. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2007, 3, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatemi, G.; Silman, A.; Bang, D.; Bodaghi, B.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Gul, A.; Houman, M.H.; Kötter, I.; Olivieri, I.; Salvarani, C.; et al. Management of Behçet disease: A systematic literature review for the European League Against Rheumatism evidence-based recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, F.N.; Ozen, G.; Ünal, A.U.; Kahraman Koytak, P.; Tuncer, N.; Direskeneli, H. Severe neuro-Behcet’s disease treated with a combination of immunosuppressives and a TNF-inhibitor. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2016, 41, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Aktulga, E.; Altac, M.; Müftüoglu, A.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Pazarli, H.; Tüzün, Y.; Yalçin, B.; Yazici, H.; Yurdakul, S. A double blind study of colchicine in Behçet’s disease. Haematologica 1980, 65, 399–402. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Y.; Sugita, S.; Tanaka, H.; Kamoi, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Mochizuki, M. Comparison of infliximab versus ciclosporin during the initial 6-month treatment period in Behçet disease. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 94, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamuryudan, V.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Hizli, N.; Mat, C.; Yurdakul, S.; Tüzün, Y.; Senocak, M.; Yazici, H. Azathioprine in Behçet’s syndrome: Effects on long-term prognosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, K.; Nakajima, A.; Urayama, A.; Nakae, K.; Kogure, M.; Inaba, G. Double-masked trial of cyclosporin versus colchicine and long-term open study of cyclosporin in Behçet’s disease. Lancet 1989, 1, 1093–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyazgan, Y.; Yurdakul, S.; Yazici, H.; Tüzün, B.; Işçimen, A.; Tüzün, Y.; Aktunç, T.; Pazarli, H.; Hamuryudan, V.; Müftüoğlu, A. Low dose cyclosporin A versus pulsed cyclophosphamide in Behçet’s syndrome: A single masked trial. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1992, 76, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davatchi, F.; Sadeghi Abdollahi, B.; Tehrani Banihashemi, A.; Shahram, F.; Nadji, A.; Shams, H.; Chams-Davatchi, C. Colchicine versus placebo in Behçet’s disease: Randomized, double-blind, controlled crossover trial. Mod. Rheumatol. 2009, 19, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirohata, S.; Suda, H.; Hashimoto, T. Low-dose weekly methotrexate for progressive neuropsychiatric manifestations in Behçet’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998, 159, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melikoglu, M.; Fresko, I.; Mat, C.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Gogus, F.; Yurdakul, S.; Hamuryudan, V.; Yazici, H. Short-term trial of etanercept in Behçet’s disease: A double blind, placebo controlled study. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 32, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, G.J.; Dick, A.D.; Brézin, A.P.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Thorne, J.E.; Kestelyn, P.; Barisani-Asenbauer, T.; Franco, P.; Heiligenhaus, A.; Scales, D.; et al. Adalimumab in patients with active noninfectious uveitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotter, I.; Zierhut, M.; Eckstein, A.K.; Vonthein, R.; Ness, T.; Günaydin, I.; Grimbacher, B.; Blaschke, S.; Peter, H.H.; Stübiger, N. Human recombinant interferon alfa-2a for the treatment of Behçet’s disease with sight threatening posterior or panuveitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deuter, C.M.; Zierhut, M.; Möhle, A.; Vonthein, R.; Stöbiger, N.; Kötter, I. Long-term remission after cessation of interferon-α treatment in patients with severe uveitis due to Behçet’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 2796–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaçmaz, O.; Kempen, J.H.; Newcomb, C.; Gangaputra, S.; Daniel, E.; Levy-Clarke, G.A.; Nussenblatt, R.B.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; Suhler, E.B.; Thorne, J.E.; et al. Ocular inflammation in Behçet disease: Incidence of ocular complications and of loss of visual acuity. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 146, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugal-Tutkun, I.; Onal, S.; Altan-Yaycioglu, R.; Huseyin Altunbas, H.; Urgancioglu, M. Uveitis in Behçet disease: An analysis of 880 patients. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 138, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy-Clarke, G.; Jabs, D.A.; Read, R.W.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; Vitale, A.; Van Gelder, R.N. Expert panel recommendations for the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor biologic agents in patients with ocular inflammatory disorders. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 785–796.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Araji, A.; Kidd, D.P. Neuro-Behçet’s disease: Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluduz, D.; Kürtüncü, M.; Yapıcı, Z.; Seyahi, E.; Kasapçopur, Ö.; Özdoğan, H.; Saip, S.; Akman-Demir, G.; Siva, A. Clinical characteristics of pediatric-onset neuro-Behçet disease. Neurology 2011, 77, 1900–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Silman, A.; Akman-Demir, G.; Bohlega, S.; Borhani-Haghighi, A.; Constantinescu, C.S.; Houman, H.; Mahr, A.; Salvarani, C.; Sfikakis, P.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Neuro-Behçet’s disease: International consensus recommendations. J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 1662–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarica-Kucukoglu, R.; Akdag-Kose, A.; KayabalI, M.; Yazganoglu, K.D.; Disci, R.; Erzengin, D.; Azizlerli, G. Vascular involvement in Behçet’s disease: A retrospective analysis of 2319 cases. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 919–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kural-Seyahi, E.; Fresko, I.; Seyahi, N.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Mat, C.; Hamuryudan, V.; Yurdakul, S.; Yazici, H. The long-term mortality and morbidity of Behçet syndrome: A 2-decade outcome survey of 387 patients followed at a dedicated center. Medicine 2003, 82, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheon, J.H.; Kim, W.H. An update on the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of intestinal Behçet’s disease. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2015, 27, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Cheon, J.H. Intestinal Behçet’s disease: A true inflammatory bowel disease or merely an intestinal complication of systemic vasculitis? Yonsei Med. J. 2016, 57, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpsoy, E. Behçet’s disease: A comprehensive review with a focus on epidemiology, etiology and clinical features, and management of mucocutaneous lesions. J. Dermatol. 2016, 43, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sula, B.; Batmaz, I.; Ucmak, D.; Yolbas, I.; Akdeniz, S. Demographical and clinical characteristics of Behcet’s Disease in southeastern Turkey. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2014, 6, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melikoglu, M.A.; Melikoglu, M. The clinical importance of lymphadenopathy in Behçet’s syndrome. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2008, 33, 402–406. [Google Scholar]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Orfanos, C.E. Treatment of Adamantiades-Behçet disease with systemic interferon alfa. Arch. Dermatol. 2000, 136, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, S.; Balta, I.; Ozturk, C.; Celik, T.; Iyisoy, A. Behçet’s disease and risk of vascular events. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2016, 31, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghembaza, A.; Boussouar, S.; Saadoun, D. Atteintes thoraciques de la maladie de Behçet [Thoracic manifestations of Behcet’s disease]. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2022, 39, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skef, W.; Hamilton, M.J.; Arayssi, T. Gastrointestinal Behçet’s disease: A review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 3801–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senusi, A.A.; Mather, J.; Ola, D.; Bergmeier, L.A.; Gokani, B.; Fortune, F. The impact of multifactorial factors on the Quality of Life of Behçet’s patients over 10 years. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 996571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, D.; Park, H.J. Behcet disease: An undifferentiating and complex vasculitis. Postgrad Med. 2023, 135, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrolia, M.V.; Marinello, D.; Di Cianni, F.; Talarico, R.; Simonini, G. Assessing quality of life in Behçet’s disease: A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2022, 40, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leccese, P.; Ozguler, Y.; Christensen, R.; Esatoglu, S.N.; Bang, D.; Bodaghi, B.; Celik, A.F.; Fortune, F.; Gaudric, J.; Gül, A.; et al. Management of skin, mucosa and joint involvement of Behçet’s syndrome: A systematic review for update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet’s syndrome. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 2019, 48, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, R.A.; Hatemi, G.; Burns, J.C.; Mohammad, A.J. Global epidemiology of vasculitis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovcharov, P.S.; Lisitsyna, T.A.; Veltishchev, D.Y.; Burenchev, D.V.; Ishchenko, D.A.; Seravina, O.F.; Kovalevskaya, O.B.; Alekberova, Z.S.; Nasonov, E.L. Kognitivnye narusheniia pri bolezni Bekhcheta [Cognitive disorders in Behçet’s disease]. Zhurnal Nevrol. Psikhiatrii im. S.S. Korsakova 2019, 119, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, M.; Sharifi, A.; Rezaei, S.; Rafiei, S.; Hosseinifard, H.; Khani, S.; Doustmehraban, M.; Rajabi, M.; Beiramy Chomalou, Z.; Soori, P.; et al. Global systematic review and meta-analysis of health-related quality of life in Behcet’s patients. Caspian J. Intern. Med. 2022, 13, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabbazi, A.; Ebrahimzadeh Attari, V.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Malek Mahdavi, A. Quality of Life in Patients With Behçet Disease and Its Relation With Clinical Symptoms and Disease Activity. Reumatol. Clin. 2021, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnoux, C.; Mahendira, D.; Laskin, C.A. Fertility and pregnancy in vasculitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnoux, C. Grossesse et vascularites [Pregnancy and vasculitides]. Presse Med. 2008, 37, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, S.; Alpsoy, E.; Durdu, M.; Akman, A. The clinical course of Behçet’s disease in pregnancy: A retrospective analysis and review of the literature. J. Dermatol. 2003, 30, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, N.; Wechsler, B.; Nizard, J.; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Boutin, D.L.T.H.; Dommergues, M.; Vauthier-Brouzes, D.; Cacoub, P.; Saadoun, D. Behçet’s disease and pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 2450–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadaon, J.; Shushan, A.; Ezra, Y.; Sela, H.Y.; Ozcan, C.; Rojansky, N. Behçet’s disease and pregnancy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2005, 84, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betti, M.; Vizza, E.; Piccione, E.; Pietropolli, A.; Chiofalo, B.; Pallocca, M.; Bruno, V. Towards reproducible research in recurrent pregnancy loss immunology: Learning from cancer microenvironment deconvolution. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1082087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, P.; Navada, S.; Amin, P. Pregnancy and Behcet’s disease—A rare case report. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India 2016, 66, 642–645. [Google Scholar]

- Marsal, S.; Falga, C.; Simeon, C.P.; Vilardell, M.; Bosch, J.A. Behçet’s disease and pregnancy relationship study. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1997, 36, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, Ü. Pregnancy and Behçet Disease. Behcet’s Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Pecorino, B.; Scibilia, G.; Rapisarda, F.; Borzì, P.; Vento, M.E.; Teodoro, M.C.; Scollo, P. Evaluation of Implantation and Clinical Pregnancy Rates after Endometrial Scratching in Women with Recurrent Implantation Failure. Ital. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2018, 30, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, B.; Généreau, T.; Biousse, V.; Vauthier-Brouzes, D.; Seebacher, J.; Dormont, D.; Piette, J.C. Pregnancy complicated by cerebral venous thrombosis in Behçet’s disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995, 173, 1627–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorino, B.; Rubino, C.; Guardalà, V.F.; Galia, A.; Scollo, P. Genetic Screening in Young Women Diagnosed with Endometrial Cancer. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 28, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskender, C.; Yasar, O.; Kaymak, O.; Yaman, S.T.; Uygur, D.; Danisman, N. Behçet’s disease and pregnancy: A retrospective analysis of course of disease and pregnancy outcome. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martineau, M.; Haskard, D.O.; Nelson-Piercy, C. Behçet’s syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet. Med. 2010, 3, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettiol, A.; Alibaz-Oner, F.; Direskeneli, H.; Hatemi, G.; Saadoun, D.; Seyahi, E.; Prisco, D.; Emmi, G. Vascular Behçet syndrome: From pathogenesis to treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadoun, D.; Bodaghi, B.; Cacoub, P. Behçet’s Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatemi, G.; Uçar, D.; Uygunoğlu, U.; Yazici, H.; Yazici, Y. Behçet Syndrome. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 49, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, H.; Seyahi, E.; Hatemi, G.; Yazici, Y. Behçet syndrome: A contemporary view. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M.F.; Aksentijevich, I.; Galon, J.; McDermott, E.M.; Ogunkolade, B.W.; Centola, M.; Mansfield, E.; Gadina, M.; Karenko, L.; Pettersson, T.; et al. Germline mutations in the extracellular domains of the 55 kDa TNF receptor, TNFR1, define a family of dominantly inherited autoinflammatory syndromes. Cell 1999, 97, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirino, Y.; Bertsias, G.; Ishigatsubo, Y.; Mizuki, N.; Tugal-Tutkun, I.; Seyahi, E.; Ozyazgan, Y.; Sacli, F.S.; Erer, B.; Inoko, H.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for Behçet’s disease and epistasis between HLA-B*51 and ERAP1. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmers, E.F.; Cosan, F.; Kirino, Y.; Ombrello, M.J.; Abaci, N.; Satorius, C.; Le, J.M.; Yang, B.; Korman, B.D.; Cakiris, A.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktas Cetin, E.; Cosan, F.; Cefle, A.; Deniz, G. IL-22-secreting Th22 and IFN-γ-secreting Th17 cells in Behçet’s disease. Mod. Rheumatol. 2014, 24, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantarini, L.; Vitale, A.; Scalini, P.; Dinarello, C.A.; Rigante, D.; Franceschini, R.; Simonini, G.; Borsari, G.; Caso, F.; Lucherini, O.M.; et al. Anakinra treatment in drug-resistant Behcet’s disease: A case series. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015, 34, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmi, G.; Talarico, R.; Lopalco, G.; Cimaz, R.; Cantini, F.; Viapiana, O.; Olivieri, I.; Goldoni, M.; Vitale, A.; Silvestri, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety profile of anti-interleukin-1 treatment in Behçet’s disease: A multicenter retrospective study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 35, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmi, G.; Bettiol, A.; Hatemi, G.; Prisco, D. Behçet’s syndrome. Lancet 2024, 403, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Recurrent Oral Ulceration | Minor, major, or herpetiform ulceration observed by a physician or patient at least 3 times in one 12-month period. |

| Plus at least two of the following | |

| Recurrent Genital Ulceration | Aphthous ulceration or scarring, observed by a physician or patient. |

| Eye Lesions | Anterior uveitis, posterior uveitis, cells in vitreous on slit lamp examination, or retinal vasculitis observed by an ophthalmologist. |

| Skin Lesions | Erythema nodosum observed by a physician or patient, pseudofolliculitis, or papulopustular lesions; or acneiform nodules consistent with Behçet’s Disease in postadolescent patients not on corticosteroid treatment. |

| Positive Pathergy Test | Read by a physician at 24–48 h. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lavalle, S.; Caruso, S.; Foti, R.; Gagliano, C.; Cocuzza, S.; La Via, L.; Parisi, F.M.; Calvo-Henriquez, C.; Maniaci, A. Behçet’s Disease, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040562

Lavalle S, Caruso S, Foti R, Gagliano C, Cocuzza S, La Via L, Parisi FM, Calvo-Henriquez C, Maniaci A. Behçet’s Disease, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Medicina. 2024; 60(4):562. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040562

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavalle, Salvatore, Sebastiano Caruso, Roberta Foti, Caterina Gagliano, Salvatore Cocuzza, Luigi La Via, Federica Maria Parisi, Christian Calvo-Henriquez, and Antonino Maniaci. 2024. "Behçet’s Disease, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment Approaches: A Comprehensive Review" Medicina 60, no. 4: 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040562

APA StyleLavalle, S., Caruso, S., Foti, R., Gagliano, C., Cocuzza, S., La Via, L., Parisi, F. M., Calvo-Henriquez, C., & Maniaci, A. (2024). Behçet’s Disease, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, and Treatment Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Medicina, 60(4), 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60040562