Is Mental Health Worse in Medical Students than in the General Population? A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

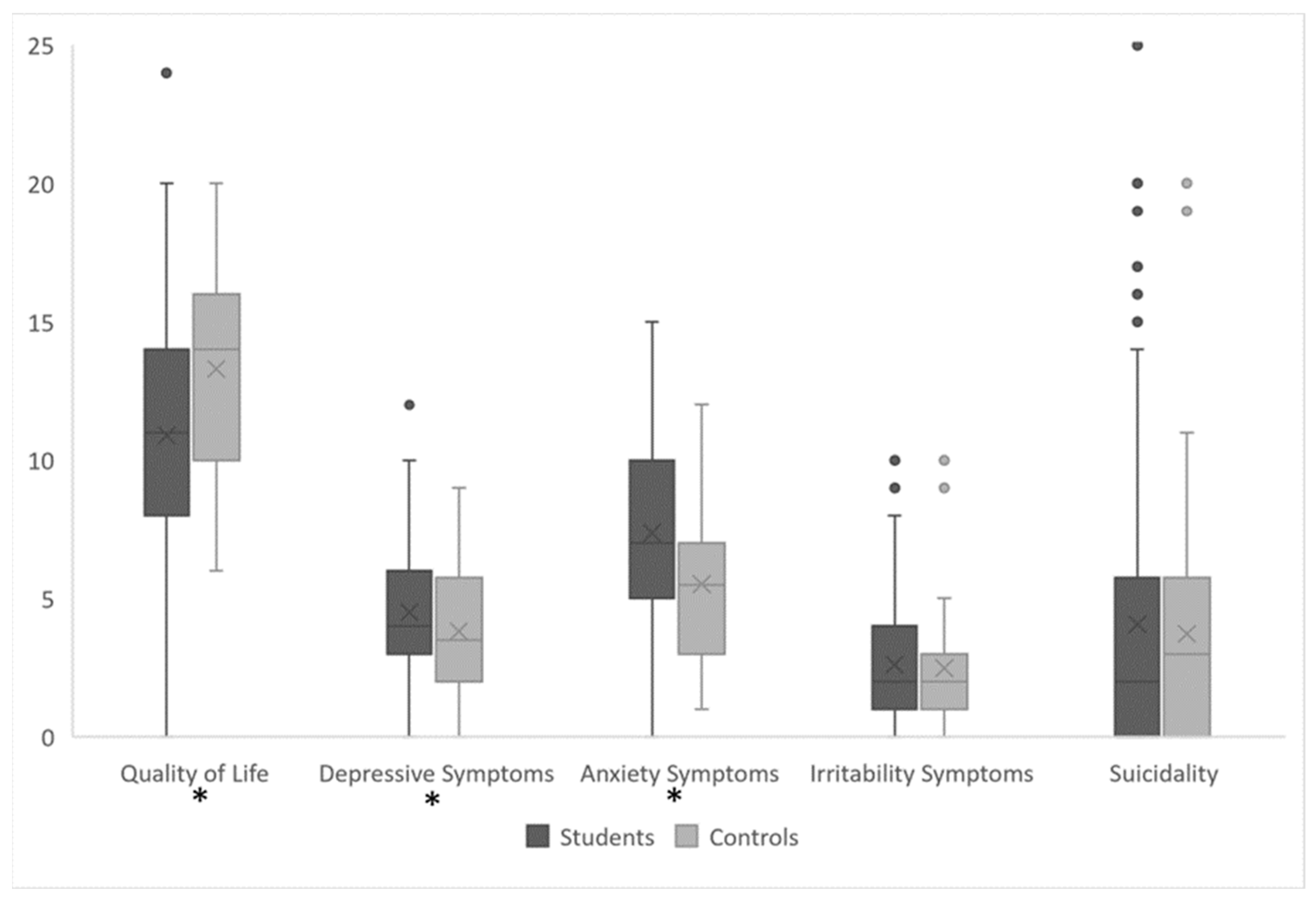

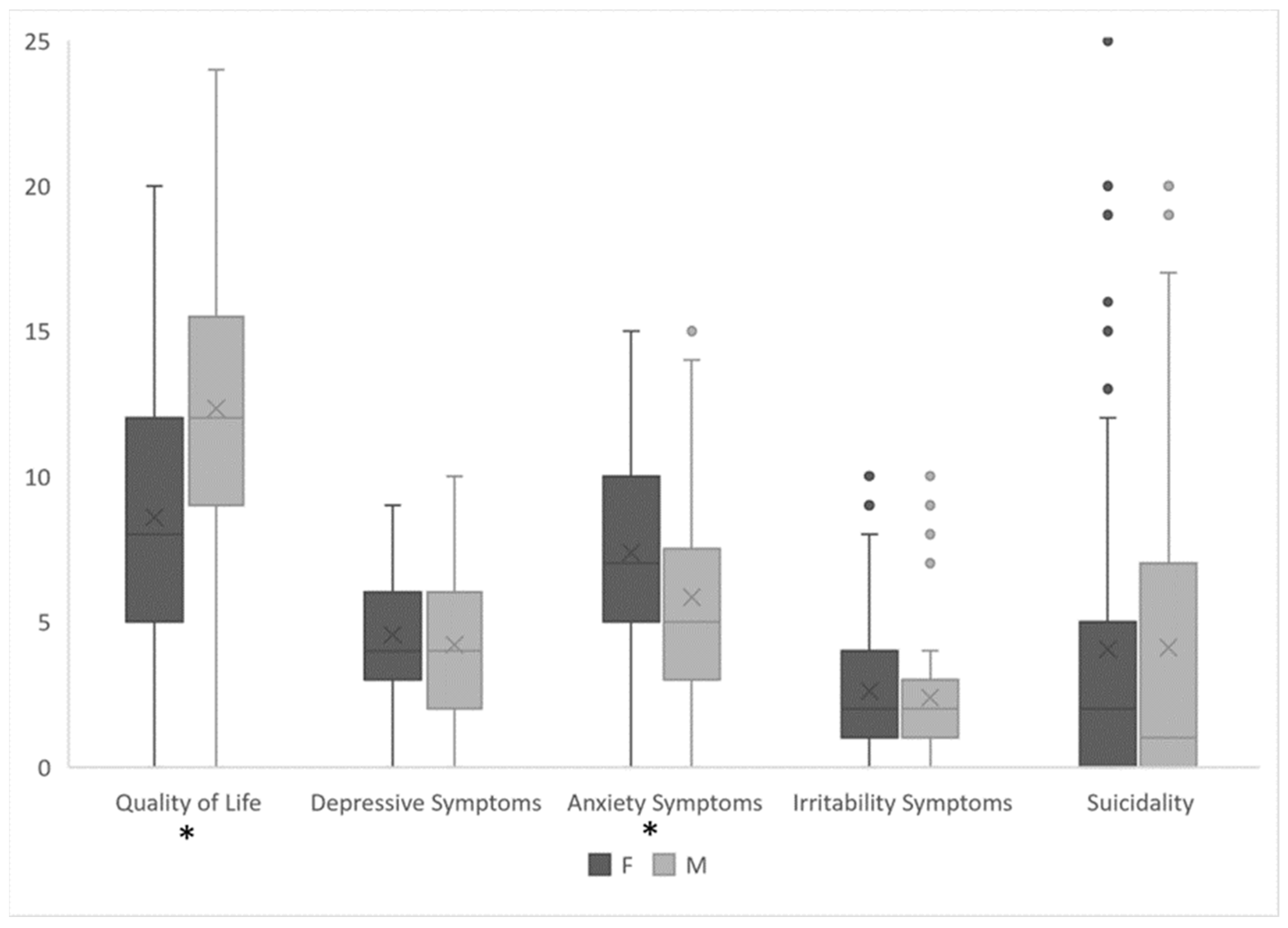

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Bias in Participant Selection: Voluntary participation may attract individuals who are more inclined to discuss their mental health. However, this bias should be balanced between the two groups.

- Medium Sample Size: The sample size of the study was moderate, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. A larger and more diverse sample would provide more robust and representative results.

- Cross-Sectional Design: This design does not allow for establishing causal relationships or the assessment of changes in mental health over time. Longitudinal studies are necessary to accurately understand the trajectories of mental health in medical students and workers.

- Reliance on Short Scales: While these scales provide a quick assessment, they may lack the depth and comprehensive evaluation of more extensive instruments. Additionally, relying on short scales may not adequately capture all the dimensions of mental health.

- Lack of In-Depth Assessment of Social Support or Academic Year: The study does not thoroughly explore the role of social support in influencing mental health outcomes. Social support is a critical factor in an individual’s well-being, and its absence or presence can significantly impact mental health. In the future, it would be interesting to investigate the effect of both factors.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pedrelli, P.; Nyer, M.; Yeung, A.; Zulauf, C.; Wilens, T. College Students: Mental Health Problems and Treatment Considerations. Acad. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, D.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Z. Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 63, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloud, T.; Bann, D. Financial stress and mental health among higher education students in the UK up to 2018: Rapid review of evidence. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, F.; Blank, L.; Cantrell, A.; Baxter, S.; Blackmore, C.; Dixon, J.; Goyder, E. Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Amminger, G.P.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Lee, S.; Ustün, T.B. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Auerbach, R.P.; Benjet, C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Ebert, D.; Karyotaki, E.; Kessler, R.C. The World Health Organization World Mental Health International College Student initiative: An overview. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 28, e1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, J.; Eisenberg, D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessauvagie, A.S.; Dang, H.M.; Nguyen, T.A.T.; Groen, G. Mental Health of University Students in Southeastern Asia: A Systematic Review. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2022, 34, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, J.P.; Giacomin, H.T.; Tam, W.W.; Ribeiro, T.B.; Arab, C.; Bezerra, I.M.; Pinasco, G.C. Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2017, 39, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Alonso, J.; Axinn, W.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hwang, I.; Kessler, R.C.; Liu, H.; Mortier, P.; et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2955–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Qiu, X.H.; Yang, X.X.; Qiao, Z.X.; Yang, Y.J.; Liang, Y. Depression among Chinese university students: Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersi, L.; Tesfay, K.; Gesesew, H.; Krahl, W.; Ereg, D.; Tesfaye, M. Mental distress and associated factors among undergraduate students at the University of Hargeisa, Somaliland: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2017, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.K.; Kelly, S.J.; Adams, C.E.; Glazebrook, C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storrie, K.; Ahern, K.; Tuckett, A. A systematic review: Students with mental health problems—A growing problem. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2010, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zivin, K.; Eisenberg, D.; Gollust, S.E.; Golberstein, E. Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 117, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruffaerts, R.; Mortier, P.; Kiekens, G.; Auerbach, R.P.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Nock, M.K.; Kessler, R.C. Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hysenbegasi, A.; Hass, S.L.; Rowland, C.R. The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2005, 8, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Furr, S.R.; Westefeld, J.S.; McConnell, G.N.; Jenkins, J.M. Suicide and depression among college students: A decade later. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2001, 32, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Du, X. Trends and prevalence of suicide 2017–2021 and its association with COVID-19: Interrupted time series analysis of a national sample of college students in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 316, 114796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.M.; Lim, C.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Alonso, J.; Bruffaerts, R.; Caldas-de-Almeida, J.M.; Florescu, S.; de Girolamo, G.; Hu, C.; de Jonge, P.; et al. Association of Mental Disorders with Subsequent Chronic Physical Conditions: World Mental Health Surveys from 17 Countries. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, D.C.R.; Capaldi, D.M. Young men’s intimate partner violence and relationship functioning: Long-term outcomes associated with suicide attempt and aggression in adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaith, R.P.; Constantopoulos, A.A.; Jardine, M.Y.; McGuffin, P. A clinical scale for the self-assessment of irritability. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 132, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ranieri, W.F. Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. J. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 44, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holi, M.M.; Pelkonen, M.; Karlsson, L.; Kiviruusu, O.; Ruuttu, T.; Heilä, H.; Tuisku, V.; Marttunen, M. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) in adolescents. BMC Psychiatry 2005, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohls, J.K.; König, H.-H.; Quirke, E.; Hajek, A. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life—A Systematic Review of Evidence from Longitudinal Observational Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemus, M.; Sarvaiya, N.; Neill Epperson, C. Sex differences in anxiety and depression: Clinical perspectives. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedat, S.; Scott, K.M.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Berglund, P.; Bromet, E.J.; Brugha, T.S.; Demyttenaere, K.; de Girolamo, G.; Haro, J.M.; Jin, R.; et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirparo, G.; Pireddu, R.; Andreassi, A.; Sechi, G.M.; Signorelli, C. Social Illness Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Regional Study. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2023, 38, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirotkin, A.V.; Pavlíková, M.; Hlad, Ľ.; Králik, R.; Zarnadze, I.; Zarnadze, S.; Petrikovičová, L. Impact of COVID-19 on University Activities: Comparison of Experiences from Slovakia and Georgia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirparo, G.; Di Fronzo, P.; Solla, D.; Bottignole, D.; Gambolò, L. Are Italian Newly Licensed Nurses Ready? A Study on Self-Perceived Clinical Autonomy in Critical Care Scenarios. Healthcare 2024, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusti, L.; Mammarella, S.; Salza, A.; Del Vecchio, S.; Ussorio, D.; Casacchia, M.; Roncone, R. Predictors of Academic Performance during the COVID-19 Outbreak: Impact of Distance Education on Mental Health, Social Cognition and Memory Abilities in an Italian University Student Sample. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N = 167) | Medical Students (N = 124) | Workers (N = 43) | p | ES[CI95%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) M(SD) | 25.1 (5.1) | 24.2 (4.3) | 27.5 (6.2) | <0.001 | D = 0.671 [0.293; 1.040] |

| Male N(%) | 62 (37.1) | 42 (33.9) | 20 (46.5) | 0.139 | OR = 0.589 [0.291; 1.190] |

| Do you think you have mental disorders? (y) N(%) | 73 (43.7) | 61 (49.2) | 12 (27.9) | 0.015 | OR = 2.50 [1.18; 5.31] |

| Do you have diagnosed mental disorders? (y) N(%) | 25 (15.0) | 22 (17.7) | 3 (7.0) | 0.135 | OR = 2.88 [0.815; 10.100] |

| Are you being treated for mental problems? (y) N(%) | 51 (30.5) | 38 (30.6) | 13 (30.2) | 0.960 | OR = 1.02 [0.479; 217] |

| Linear Regression to Predict QoL | ||||

| Adaptation of Models | ||||

| Model | R2 | p | ||

| 1 (Age) | 0.016 | 0.159 | ||

| 2 (Age; Biological Sex) | 0.126 | <0.001 | ||

| 3 (Age; Biological Sex; Psychopathology) | 0.502 | <0.001 | ||

| Anova | ||||

| Sum of Squares | df | F | p | |

| Age | 3.39 | 1 | 0.362 | 0.549 |

| Biological Sex | 39.51 | 1 | 4.221 | 0.042 |

| Depression | 236.29 | 1 | 25.246 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 82.22 | 1 | 8.784 | 0.004 |

| Irritability | 4.25 | 1 | 0.454 | 0.502 |

| Suicidality | 2.46 | 1 | 0.263 | 0.609 |

| Model Coefficients | ||||

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | T | p |

| Intercept | 18.906 | 1.656 | 11.415 | <0 .001 |

| Age | −0.040 | 0.066 | −0.602 | 0.549 |

| Biological Sex: F-M | −1.359 | 0.662 | −2.054 | 0.042 |

| Depression | −0.755 | 0.150 | −5.024 | <0 .001 |

| Anxiety | −0.357 | 0.121 | −2.964 | 0.004 |

| Irritability | −0.085 | 0.126 | −0.674 | 0.502 |

| Suicidality | −0.033 | 0.065 | −0.513 | 0.609 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stirparo, G.; Pireddu, R.; D’Angelo, M.; Bottignole, D.; Mazzoli, R.; Gambolò, L. Is Mental Health Worse in Medical Students than in the General Population? A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060863

Stirparo G, Pireddu R, D’Angelo M, Bottignole D, Mazzoli R, Gambolò L. Is Mental Health Worse in Medical Students than in the General Population? A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina. 2024; 60(6):863. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060863

Chicago/Turabian StyleStirparo, Giuseppe, Roberta Pireddu, Marta D’Angelo, Dario Bottignole, Riccardo Mazzoli, and Luca Gambolò. 2024. "Is Mental Health Worse in Medical Students than in the General Population? A Cross-Sectional Study" Medicina 60, no. 6: 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060863

APA StyleStirparo, G., Pireddu, R., D’Angelo, M., Bottignole, D., Mazzoli, R., & Gambolò, L. (2024). Is Mental Health Worse in Medical Students than in the General Population? A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina, 60(6), 863. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060863