Depression in the Perinatal Period: Course and Outcome of Depression in the Period from the Last Trimester of Pregnancy to One Year after Delivery in Primiparous Mothers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

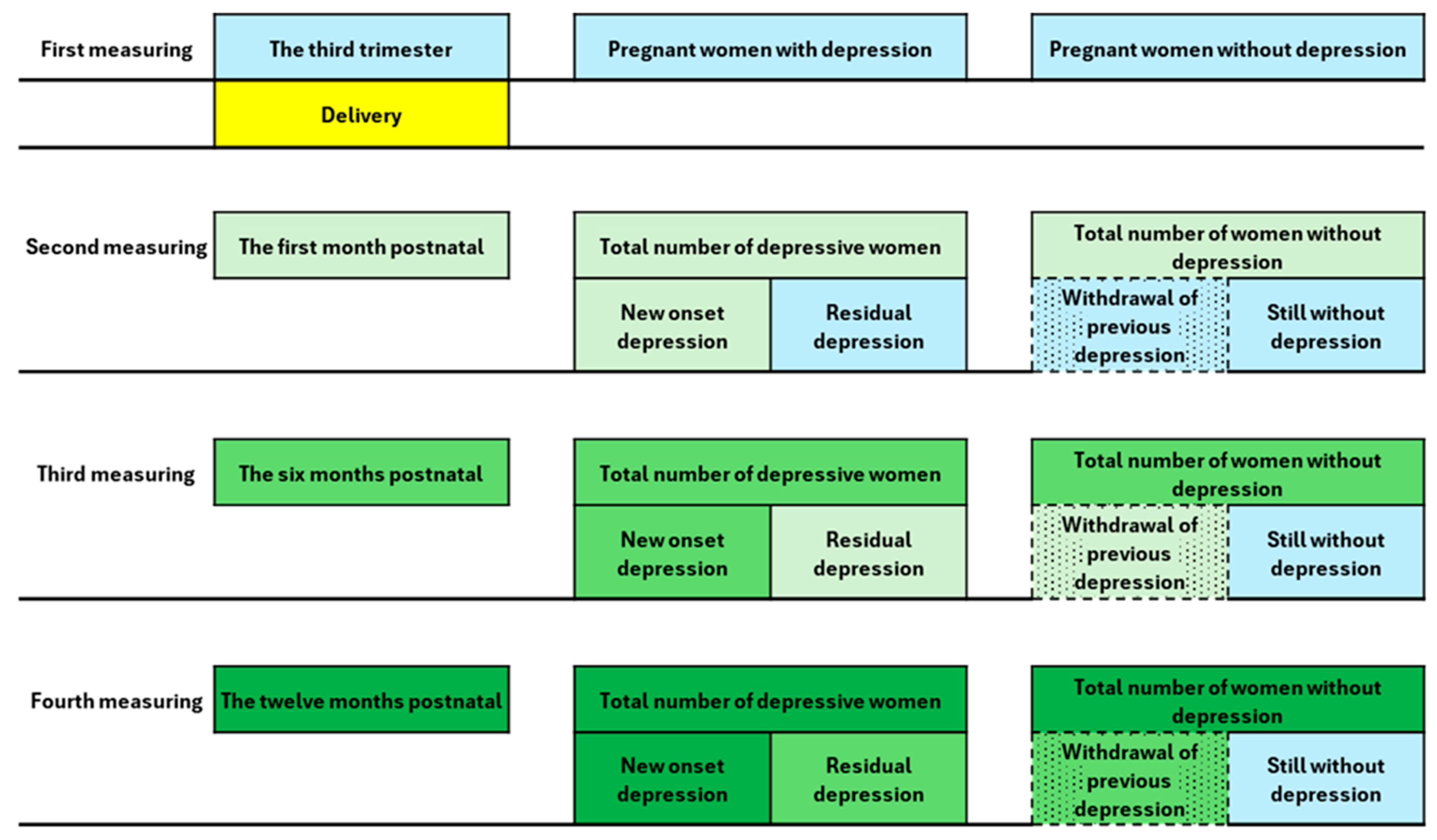

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Study Setting, Sample, and Study Calculation

2.3. Assessment Methods

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Group Structure

3.2. Depressive Episodes

Global Assessment of Depression in the Examined Period

3.3. Prevalence of Depressive Symptomatology at Different Time Points

3.4. New-Onset Depression, Residual Depression, and Outcome

3.5. Sociodemographic, Obstetric, and Psychological Factors and Perinatal Depression

3.6. Bipolar Hypomanic/Manic Symptomatology at Each Time Point

4. Discussio

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Abri, K.; Edge, D.; Armitage, C.J. Armitage. Prevalence and correlates of perinatal depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 58, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmitrovic, B.K.; Dugalić, M.G.; Balkoski, G.N.; Dmitrovic, A.; Soldatovic, I. Frequency of perinatal depression in Serbia and associated risk factors. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 60, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebeka, S.; Le Strat, Y.; Higgons, A.D.P.; Benachi, A.; Dommergues, M.; Kayem, G.; Lepercq, J.; Luton, D.; Mandelbrot, L.; Ville, Y.; et al. Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression and environmental factors: The IGEDEPP cohort. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 138, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Okada, T.; Morikawa, M.; Yamauchi, A.; Sato, M.; Ando, M.; Ozaki, N. Perinatal depression and anxiety of primipara is higher than that of multipara in Japanese women. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, H.; Riddle, J.N.; Salimgaraev, R.; Zhaunova, L.; Payne, J.L. Risk factors associated with postpartum depressive symptoms: A multinational study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 301, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.-L.H.; Strøm, M.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Videbech, P.; Melbye, M. Risk, treatment duration, and recurrence risk of postpartum affective disorder in women with no prior psychiatric history: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serati, M.; Redaelli, M.; Buoli, M.; Altamura, A.C. Perinatal major depression biomarkers: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 193, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G.A.; Hugunin, J.; Xu, L.; Ulbricht, C.M.; Simas, T.A.M.; Ko, J.Y.; Byatt, N. Prevalence of bipolar disorder in perinatal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 83, 41785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banti, S.; Mauri, M.; Oppo, A.; Borri, C.; Rambelli, C.; Ramacciotti, D.; Montagnani, M.S.; Camilleri, V.; Cortopassi, S.; Rucci, P.; et al. From the third month of pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Prevalence, incidence, recurrence, and new onset of depression. Results from the Perinatal Depression–Research & Screening Unit study. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Weinberger, T.; Chandy, A.; Schmukler, S. Depression during pregnancy and postpartum. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.; Cox, J.L. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDDS). J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 1990, 8, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odalovic, M.; Tadic, I.; Lakic, D.; Nordeng, H.; Lupattelli, A.; Tasic, L. Translation and factor analysis of structural models of Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Serbian pregnant and postpartum women–Web-based study. Women Birth 2015, 28, e31–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanov, J.; Stankovic, M.; Zikic, O.; Stojanov, A. The relationship between alexithymia and risk for postpartum depression. Psychiatr. Ann. 2021, 51, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, J.; Stankovic, M.; Zikic, O.; Stankovic, M.; Stojanov, A. The risk for nonpsychotic postpartum mood and anxiety disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2021, 56, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICD-11. Available online: https://icd.who.int/en (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Minimising, H.; Hope, M.; Household, A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Trajanovic, N.; Djuric, V.; Latas, M.; Milovanovic, S.; Jovanovic, A.; Djuric, D. Serbian translation of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: Psychometric properties and the new methodological approach in translating scales. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2013, 141, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanov, J.; Stojanov, A. A cross-sectional study of alexithymia in patients with relapse remitting form of multiple sclerosis. J. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 66, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.J.; Ryan, D.; Bagby, M. Toward the development of a new self-report alexithymia scale. Psychother. Psychosom. 1985, 44, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barut, S.; Uçar, T.; Yılmaz, A.N. Comparison of pregnant women’s anxiety, depression and birth satisfaction based, on their traumatic childbirth perceptions. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 2729–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, R.M.; Williams, J.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Calabrese, J.R.; Flynn, L.; Keck, P.E., Jr.; Lewis, L.; McElroy, S.L.; Post, R.M.; Rapport, D.J.; et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1873–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.R.; Woo, Y.S.; Ahn, H.S.; Ahn, I.M.; Kim, H.J.; Bahk, W.-M. The validity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for screening bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2015, 32, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, B.N.; Simpson, W.; Wright, L.; Steiner, M. and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire as a screening tool for bipolar disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 19247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josefsson, A.; Berg, G.; Nordin, C.; Sydsjo, G. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in late pregnancy and postpartum. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2001, 80, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, G. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.R.; Gordon, H.; Lindquist, A.; Walker, S.P.; Homer, C.S.E.; Middleton, A.; Cluver, C.A.; Tong, S.; Hastie, R. Prevalence of perinatal depression in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simas, T.A.M.; Whelan, A.; Byatt, N. Postpartum depression—New screening recommendations and treatments. JAMA 2023, 330, 2295–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M.P.; Goldberg, J.F. The Pursuit to Recognize Bipolar Disorder in Pregnant and Postpartum Women. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 83, 41776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosander, M.; Berlin, A.; Frykedal, K.F.; Barimani, M. Maternal depression symptoms during the first 21 months after giving birth. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschmann, M.; Rosen, K.; Gievers, L.; Hildebrand, A.; Laird, A.; Khaki, S. Evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on postpartum depression. J. Women’s Health 2022, 31, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, A.-M.; Webb, R.; Enea, V. Self-criticism and self-compassion as mediators of the relationship between alexithymia and postpartum depressive symptoms. Psihologija 2023, 56, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, B.F.; Kearney, J. Risk factors for postpartum depression: An umbrella review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2020, 65, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | Urban area | 177 | 94.1 |

| Suburban environment | 11 | 5.9 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 9 | 4.8 |

| 25–35 | 149 | 79.3 | |

| >35 | 30 | 16 | |

| Educational level | ≤12 years of schooling | 45 | 23.9 |

| >13 years of schooling | 143 | 76.1 | |

| Employment | Employed | 133 | 70.7 |

| Unemployed | 55 | 29.3 | |

| Partnership status | Marriage/Cohabitation | 172 | 91.5 |

| Without partner | 16 | 8.5 | |

| Depressive Episode | Last Trimester | One Month after Giving Birth | Six Months after Giving Birth | Twelve Months after Giving Birth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Present | 20 | 10.6 | 55 | 29.3 | 50 | 26.6 | 47 | 25 |

| Absent | 168 | 89.4 | 133 | 70.7 | 138 | 73.4 | 141 | 75 |

| Total | 188 | 100.0 | 188 | 100 | 188 | 100 | 188 | 100 |

| 1 Month Postpartum | 1–6 Months Postpartum | 6–12 Months Postpartum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With depression | New-onset depression | 25.0% | 17.0% | 0.5% |

| Residual depression | 4.3% | 9.0% | 24.5% | |

| Without depression | Withdrew from depression | 6.4% | 20.7% | 2.1% |

| Without depression | 64.4% | 53.2% | 72.9% | |

| New-Onset Depression | Residual Depression | Withdrawal from Depression | Without Depression | X2 | df | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partnership status | With partner | 18.6% | 8.1% | 2.9% | 70.3% | 8833 | 3 | 0.032 |

| Without partner | 50.0% | 6.3% | 0.0% | 43.8% | ||||

| Economic status | Satisfactory | 19.4% | 7.8% | 2.8% | 70.0% | 16,977 | 6 | 0.009 |

| Unsatisfactory | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ||||

| Already in debt | 25.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 50.0% | ||||

| Suicidality in family | Yes | 71.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 28.6% | 11,036 | 3 | 0.012 |

| No | 19.3% | 8.3% | 2.8% | 69.6% | ||||

| Complications during childbirth | Yes | 10.2% | 5.1% | 5.1% | 79.7% | 9482 | 3 | 0.024 |

| No | 26.4% | 9.3% | 1.6% | 62.8% | ||||

| Anxiety 1 month postnatal | High | 17.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 82.6% | 15,634 | 6 | 0.016 |

| Moderate | 37.5% | 37.5% | 0.0% | 25.0% | ||||

| Mild | 21.0% | 7.6% | 3.2% | 68.2% | ||||

| Alexithymia in the third trimester | Alexithymia | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 17,023 | 6 | 0.009 |

| Borderline alexithymia | 56.3% | 6.3% | 0.0% | 37.5% | ||||

| No alexithymia | 17.5% | 8.2% | 2.9% | 71.3% | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zikic, O.; Stojanov, J.; Kostic, J.; Nikolic, G.; Tosic Golubovic, S.; Simonovic, M.; Djordjevic, V.; Binic, I. Depression in the Perinatal Period: Course and Outcome of Depression in the Period from the Last Trimester of Pregnancy to One Year after Delivery in Primiparous Mothers. Medicina 2024, 60, 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060970

Zikic O, Stojanov J, Kostic J, Nikolic G, Tosic Golubovic S, Simonovic M, Djordjevic V, Binic I. Depression in the Perinatal Period: Course and Outcome of Depression in the Period from the Last Trimester of Pregnancy to One Year after Delivery in Primiparous Mothers. Medicina. 2024; 60(6):970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060970

Chicago/Turabian StyleZikic, Olivera, Jelena Stojanov, Jelena Kostic, Gordana Nikolic, Suzana Tosic Golubovic, Maja Simonovic, Vladimir Djordjevic, and Iva Binic. 2024. "Depression in the Perinatal Period: Course and Outcome of Depression in the Period from the Last Trimester of Pregnancy to One Year after Delivery in Primiparous Mothers" Medicina 60, no. 6: 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060970

APA StyleZikic, O., Stojanov, J., Kostic, J., Nikolic, G., Tosic Golubovic, S., Simonovic, M., Djordjevic, V., & Binic, I. (2024). Depression in the Perinatal Period: Course and Outcome of Depression in the Period from the Last Trimester of Pregnancy to One Year after Delivery in Primiparous Mothers. Medicina, 60(6), 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60060970