Anxiety Evolution among Healthcare Workers—A Prospective Study Two Years after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic Including Occupational and Psychoemotional Variables

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Procedure and Participants

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.3.1. Generalized Anxiety [Time Point 1, 2 and 3]

2.3.2. Sociodemographic and Occupational Variables [Time Point 1]

2.3.3. Personality Variables [Time Points 1 and 2]

- -

- Social support [time point 1]: measured using the Spanish version [44] of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [45], which is composed of 12 items divided into three dimensions: family, friends, and significant others, with a 7-point Likert-type response scale (from 1 “completely disagree” to 7 “completely agree”). The final score comes from the sum of its three subscales. The instrument has good properties [46,47], and for our study, its reliability was α = 0.85 for the general questionnaire, while for the subscales, the α values obtained were 0.81, for family, 0.82 for friends, and 0.79 for significant others.

- -

- Self-efficacy [time point 1]: The Spanish version of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) [48] was used, consisting of 10 Likert-type items scoring from 1 “completely disagree” to 4 “completely agree,” with the total score ranging from 10 to 40. This instrument, in our study, presented high internal consistency α = 0.91.

- -

- Resilience [time point 1]: we used the Spanish version of the Resilience Questionnaire (RS-14) [49], made up of 14 Likert-type items with 7 alternatives, scoring from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”, with a total score ranging from 14 to 98, whereby higher scores indicate greater resilience. In our study, α was 0.94.

- -

- Cognitive Fusion [time point 2]: The Spanish version [50] of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ) [51] was administered, which is made up of 7 Likert-type items with 7 response options, ranging from 1 “never” to 7 “always”, whereby higher scale scores imply a higher degree of cognitive fusion. A Cronbach’s α of 0.97 was obtained for our study.

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sociodemographic, Occupational, and Personality Variables of the Sample

3.2. Description of Anxiety in HCWs and Its Evolution over Time

3.3. Associations between Anxiety and Sociodemographic, Professional, Occupational, Health, and Personality Variables of the Sample

3.4. Linear Regression Analysis between Anxiety and Personality Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Labrague, L.J. Psychological Resilience, Coping Behaviours and Social Support among Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiani, F.J.; Cairoli, F.R.; Sarotto, L.; Yaryour, C.; Basile, M.E.; Duarte, J.M. Prevalence of Stress, Burnout Syndrome, Anxiety and Depression among Physicians of a Teaching Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2021, 119, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Çelmeçe, N.; Menekay, M. The Effect of Stress, Anxiety and Burnout Levels of Healthcare Professionals Caring for COVID-19 Patients on Their Quality of Life. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, V.; Durante, A.; Ambrosca, R.; Arcadi, P.; Graziano, G.; Pucciarelli, G.; Simeone, S.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Cicolini, G. Anxiety, Sleep Disorders and Self-Efficacy among Nurses during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Large Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasen, A.A.; Seid, A.A.; Mohammed, A.A. Anxiety and Stress among Healthcare Professionals during COVID-19 in Ethiopia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wu, M.; Ho, C.; Wang, J. Risks of Treated Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia among Nurses: A Nationwide Longitudinal Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Hajiesmaeili, M.; Kangasniemi, M.; Fornés-Vives, J.; Hunsucker, R.L.; Rahimibashar, F.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Farrokhvar, L.; Miller, A.C. Effects of Stress on Critical Care Nurses: A National Cross-Sectional Study. J. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 34, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zheng, H.; Liu, H.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, W. Anxiety and Its Association with Perceived Stress and Insomnia among Nurses Fighting against COVID-19 in Wuhan: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 2654–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Insomnia among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Vilagut, G.; Alayo, I.; Ferrer, M.; Amigo, F.; Aragón-Peña, A.; Aragonès, E.; Campos, M.; Del Cura-González, I.; Urreta, I.; et al. Mental Impact of COVID-19 among Spanish Healthcare Workers. A Large Longitudinal Survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpino, F.M.; da Silva, C.N.; Jerônimo, J.S.; Mulling, E.S.; da Cunha, L.L.; Weymar, M.K.; Alt, R.; Caputo, E.L.; Feter, N. Prevalence of Anxiety during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of over 2 Million People. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 318, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassannia, L.; Taghizadeh, F.; Moosazadeh, M.; Zarghami, M.; Taghizadeh, H.; Dooki, A.F.; Fathi, M.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R.; Hedayatizadeh-Omran, A.; Dehghan, N. Anxiety and Depression in Health Workers and General Population During COVID-19 in IRAN: A Cross-Sectional Study. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2021, 41, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismael, S.T.; Manoharan, G.; George, A.; Al-Kaisi, K.; Abas, S.; Al-Musabi, M.; Prasad Rao, S.; Singh, R.; Kiely, N. UK CoPACK Study: Knowledge and Confidence of Healthcare Workers in Using Personal Protective Equipment and Related Anxiety Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Med. 2023, 23, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio-Martínez, M.L.; Malca-Casavilca, M.; Condor-Rojas, Y.; Becerra-Bravo, M.A.; Ruiz Ramirez, E. Factors associated with the development of stress, anxiety and depression in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in Peruvian healthcare facilities. Arch. Prev. Riesgos Labor. 2022, 25, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bui, E.; Foghi, C.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Atti, A.R.; Buselli, R.; Di Paolo, M.; Goracci, A.; Malacarne, P.; et al. The Interplay between Acute Post-Traumatic Stress, Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms on Healthcare Workers Functioning during the COVID-19 Emergency: A Multicenter Study Comparing Regions with Increasing Pandemic Incidence. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 298, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oteir, A.O.; Nazzal, M.S.; Jaber, A.F.; Alwidyan, M.T.; Raffee, L.A. Depression, Anxiety and Insomnia among Frontline Healthcare Workers amid the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e050078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılıç, A.; Gürcan, M.B.; Aktura, B.; Şahin, A.R.; Kökrek, Z. Prevalence of Anxiety and Relationship of Anxiety with Coping Styles and Related Factors in Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saddik, B.; Elbarazi, I.; Temsah, M.-H.; Saheb Sharif-Askari, F.; Kheder, W.; Hussein, A.; Najim, H.; Bendardaf, R.; Hamid, Q.; Halwani, R. Psychological Distress and Anxiety Levels Among Health Care Workers at the Height of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Meng, X.; Li, L.; Hu, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z.; Ma, X.; Xu, D.; Xing, Z.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms of Healthcare Workers in Intensive Care Unit Under the COVID-19 Epidemic: An Online Cross-Sectional Study in China. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 603273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novilla, M.L.B.; Moxley, V.B.A.; Hanson, C.L.; Redelfs, A.H.; Glenn, J.; Donoso Naranjo, P.G.; Smith, J.M.S.; Novilla, L.K.B.; Stone, S.; Lafitaga, R. COVID-19 and Psychosocial Well-Being: Did COVID-19 Worsen U.S. Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Burnout, Anxiety, and Depression? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, Q.-H.; Tran, N.-N.; Than, M.-H.; Nguyen, H.-T.; Bui, V.-S.; Nguyen, D.-H.; Vo, H.-L.; Do, T.-T.; Pham, N.-T.; Nguyen, T.-K.; et al. Depression, Anxiety and Associated Factors among Frontline Hospital Healthcare Workers in the Fourth Wave of COVID-19: Empirical Findings from Vietnam. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motahedi, S.; Aghdam, N.F.; Khajeh, M.; Baha, R.; Aliyari, R.; Bagheri, H.; Mardani, A. Anxiety and Depression among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; Alkhalifah, J.M.; Alshammari, N.F.; Alnufaie, W.S. Comparison of Generalized Anxiety and Sleep Disturbance among Frontline and Second-Line Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Wen, W.; Ma, J.; Wu, J.; Huang, S.; Qin, P. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms among Healthcare Workers in the Post-Pandemic Era of COVID-19 at a Tertiary Hospital in Shenzhen, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1094776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in the General Population: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Dai, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Ren, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Fu, J.; Chen, X.; Xiao, W.; et al. Prevalence and Influencing Factors of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms among Hospital-Based Healthcare Workers during the Surge Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Chinese Mainland: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. QJM 2023, 116, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A.; Bu, F. Trajectories of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms during Enforced Isolation Due to COVID-19 in England: A Longitudinal Observational Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.W.; Jagger, M.A.; Horney, J.A.; Kintziger, K.W. Changes in Anxiety and Depression among Public Health Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2023, 96, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, R.-X.; Chen, L.; He, C.K.; Wang, C.-Y.; Ke, J.-J.; Wang, Y.-L.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Song, X.-M. Psychological Status among Anesthesiologists and Operating Room Nurses during the Outbreak Period of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 574143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hedrera, F.J.; Gil-Almagro, F.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; Catalá-Mesón, P.; Velasco-Furlong, L. Intensive Care Unit Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: Social and Work-Related Variables, COVID-19 Symptoms, Worries, and Generalized Anxiety Levels. Acute Crit. Care 2021, 36, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.; Schroeder, S.; Leighton, K. Anxiety, Depression, Stress, Burnout, and Professional Quality of Life among the Hospital Workforce during a Global Health Pandemic. J. Rural Health 2022, 38, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Li, C.; Zhu, X.; Yan, J.; Liu, J. Prevalence of and Risk Factors Associated with Sleep Disturbances among HPCD Exposed to COVID-19 in China. Sleep Med. 2021, 80, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holton, S.; Wynter, K.; Peeters, A.; Georgalas, A.; Yeomanson, A.; Rasmussen, B. Psychological Wellbeing of Australian Community Health Service Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Caldas de Almeida, T.; Fialho, M.; Rasga, C.; Martiniano, H.; Santos, O.; Virgolino, A.; Vicente, A.M.; Heitor, M.J. Mental Health of Healthcare Professionals: Two Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauss, K.; Bardeen, J.R. The Interactive Effect of Mental Contamination and Cognitive Fusion on Anxiety. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-Q.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kong, S.; Baker, J.S.; Zhang, H. Occupational Stressors, Mental Health, and Sleep Difficulty among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Roles of Cognitive Fusion and Cognitive Reappraisal. J. Context Behav. Sci. 2021, 19, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Almagro, F.; García-Hedrera, F.J.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. From Anxiety to Hardiness: The Role of Self-Efficacy in Spanish CCU Nurses in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina 2024, 60, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, X.; Du, Q.; Zhang, J.; Mo, J.; Chen, Z.; Ning, Y.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Mental Health Symptoms in Community Epidemic Prevention Workers during the Postpandemic Era of COVID-19 in China. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 304, 114132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining Power and Sample Size for Simple and Complex Mediation Models. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; Fernández-Fernández, B.; Carmona-Torres, J.M.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; Romero-Gómez, B.; Rodríguez-Cañamero, S.; Barroso-Corroto, E.; Santacruz-Salas, E. Longitudinal Study of the Mental Health, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Stress of Senior Nursing Students to Nursing Graduates during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubin, J.; Delmas, P.; Gilles, I.; Oulevey Bachmann, A.; Ortoleva Bucher, C. Factors Protecting Swiss Nurses’ Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Campayo, J.; Zamorano, E.; Ruiz, M.A.; Pardo, A.; Pérez-Páramo, M.; López-Gómez, V.; Freire, O.; Rejas, J. Cultural Adaptation into Spanish of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Scale as a Screening Tool. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2010, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, C.; Ferrando, P.J.; Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Gómez-Sánchez, D.; Fernández-Montes, A.; Palacín-Lois, M.; Antoñanzas-Basa, M.; Rogado, J.; Manzano-Fernández, A.; Ferreira, E.; et al. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) in Cancer Patients: Psychometric Properties and Measurement Invariance. Psicothema 2021, 33, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric Characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar]

- Clara, I.P.; Cox, B.J.; Enns, M.W.; Murray, L.T.; Torgrudc, L.J. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Clinically Distressed and Student Samples. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 81, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, G.D.; Walker, R.R. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support: A Confirmation Study. J. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 47, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Las Cuevas, C.; Peñate, W. Validation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale in Psychiatric Outpatient Care. Psicothema 2015, 27, 410–415. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D.; Robles-Bello, M.A. Escala de Resiliencia 14 Ítems (RS-14): Propiedades Psicométricas de La Versión En Español. [14-Item Resilience Scale (RS)-14): Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version.]. Rev. Iberoam. Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicol. 2015, 40, 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Moreno, P.; Márquez-González, M.; Losada, A.; Gillanders, D.; Fernández-Fernández, V. Cognitive Fusion in Dementia Caregiving: Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the “Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behav. Psychol. 2014, 22, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gillanders, D.T.; Bolderston, H.; Bond, F.W.; Dempster, M.; Flaxman, P.E.; Campbell, L.; Kerr, S.; Tansey, L.; Noel, P.; Ferenbach, C.; et al. The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behav. Ther. 2014, 45, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, G.P.A.; Fracarolli, I.F.L.; Dos Santos, H.E.C.; de Oliveira, S.A.; Martins, B.G.; Junior, L.J.S.; Marziale, M.H.P.; Rocha, F.L.R. Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Health Professionals in the COVID-19 Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Martín-Pereira, J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Martínez-Riera, J.R.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on the mental health of healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2020, 94, e202007088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Savitsky, B.; Findling, Y.; Ereli, A.; Hendel, T. Anxiety and Coping Strategies among Nursing Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 46, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Prasad, A.S.; Dixit, P.K.; Padmakumari, P.; Gupta, S.; Abhisheka, K. Survey of Prevalence of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms among 1124 Healthcare Workers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic across India. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2021, 77, S404–S412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro-Morillo, A.; Boulayoune-Zaagougui, S.; Cantón-Habas, V.; Molina-Luque, R.; Hernández-Ascanio, J.; Ventura-Puertos, P.E. Emotional Universe of Intensive Care Unit Nurses from Spain and the United Kingdom: A Hermeneutic Approach. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2020, 59, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Fuentesa, M.; Molero-Juradoa, M.M.; Gázquez-Linaresb, J.; Simón-Márquez, M. Analysis of Burnout Predictors in Nursing: Risk and Protective Psychological Factors. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2019, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portero de la Cruz, S.; Cebrino, J.; Herruzo, J.; Vaquero-Abellán, M. A Multicenter Study into Burnout, Perceived Stress, Job Satisfaction, Coping Strategies, and General Health among Emergency Department Nursing Staff. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvaldi, M.; Mallet, J.; Dubertret, C.; Moro, M.R.; Guessoum, S.B. Anxiety, Depression, Trauma-Related, and Sleep Disorders among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 126, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lill, M.W. Critical Care Needs Nurses with Advanced Degrees at the Bedside. Am. J. Crit. Care 2014, 23, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, C.J.; Rahme, D.; Fakih, L.; Assaf, S.A.; Redlich, C.A.; Slade, M.D.; Fakhreddine, M.; Usta, J.; Musharrafieh, U.; Maalouf, G.; et al. Anxiety Among Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic in Lebanon: The Importance of the Work Environment and Personal Resilience. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagne, H.; Atnafu, A.; Alemu, K.; Azale, T.; Yitayih, S.; Dagnew, B.; Maru Alemayehu, A.; Andualem, Z.; Mequanent Sisay, M.; Tadesse, D.; et al. Anxiety and Associated Factors among Ethiopian Health Professionals at Early Stage of COVID-19 Pandemic in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kail, B.L.; Carr, D.C. Structural Social Support and Changes in Depression During the Retirement Transition: “I Get by With a Little Help from My Friends”. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaso, A.; Adams, J.; Peng, W.; Sibbritt, D. The Relationship between Social Support and Mental Health Problems during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, D.; Li, S.; Yang, N. The Effects of Social Support on Sleep Quality of Medical Staff Treating Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2020, 26, e923549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafari, R.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Rouhi, M.; Osouli Tabrizi, S. Mental Health and Its Relationship with Social Support in Iranian Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.; Roche, M.; Delgado, C.; Cuzzillo, C.; Giandinoto, J.-A.; Furness, T. Resilience and Mental Health Nursing: An Integrative Review of International Literature. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderberg, J.L.; Baker, L.D.; Kalantar, E.A.; Berghoff, C.R. Cognitive Fusion Accounts for the Relation of Anxiety Sensitivity Cognitive Concerns and Rumination. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 4475–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xie, X.; Tian, H.; Wu, T.; Liu, C.; Huang, K.; Gong, R.; Yu, Y.; Luo, T.; Jiao, R.; et al. Mental Fatigue and Negative Emotion among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 8123–8131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maben, J.; Bridges, J. COVID-19: Supporting Nurses’ Psychological and Mental Health. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2742–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Read, E.A. The Effect of Authentic Leadership, Person-Job Fit, and Civility Norms on New Graduate Nurses’ Experiences of Coworker Incivility and Burnout. J. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 46, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables Collected at Different Time Point | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Evaluation Period | 2nd Evaluation Period | 3rd Evaluation Period | |

| 5 May–21 June (2020) | 9 January–9 April (2021) | 11 April–15 July (2022) | |

| Symptoms | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety |

| Sociodemographics | Age, gender, family situation, work experience, job category, service, workload, avaliability PPE, concern about contagion, request of psychological support | ||

| Personality | Resilience Self-efficacy Social Support | Cognitive Fusion | |

| Anxiety | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Moment 1 | Time Moment 2 | Time Moment 3 | |||||||||||

| f (%) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Test | p | Mean (SD) | Test | p | Mean (SD) | r2 | p | |||

| Age | 43.68 (9.78) | r2 | −0.132 | 0.034 | −0.089 | 0.153 | −0.018 | 0.773 | |||||

| Experience (years) | 10.70 (9.23) | r2 | −0.125 | 0.046 | −0.033 | 0.600 | −0.031 | 0.626 | |||||

| Gender | Man | 47 (18.3%) | 7.95 (5.84) | t | −3.746 | <0.001 | 6.04 (4.91) | −3.965 | <0.001 | 5.54 (5.10) | −2.993 | 0.003 | |

| Woman | 210 (81.7%) | 11.46 (5.68) | 9.47 (5.33) | 8.06 (5.04) | |||||||||

| Professional Category | Physician | 65 (25.3%) | 9.29 (5.44) | F | 3.075 | 0.048 | 8.32 (5.06) | 0.503 | 0.605 | 6.78 (4.89) | 1.238 | 0.292 | |

| Nurse | 151 (58.8%) | 11.27 (5.89) | 9.12(5.49) | 7.80 (4.90) | |||||||||

| Nursing tecnician | 41 (16.0%) | 11.61 (6.10) | 8.73 (5.72) | 8.22 (6.20) | |||||||||

| Cohabitation | Without a partner | 77 (30.0%) | 9.97 (5.87) | t | −1.526 | 0.128 | 8.321 (5.37) | −1.030 | 0.304 | 6.87 (5.14) | −1.518 | 0.130 | |

| With a partner | 180 (70.0%) | 11.19 (5.84) | 9.08 (5.42) | 7.93 (5.11) | |||||||||

| Workload | Lower than usual | 19 (7.4%) | 6.21 (5.39) | t | −5.489 | <0.001 | 5.05 (4.12) | −3.366 | 0.001 | 5.63 (5.42) | −1.841 | 0.067 | |

| Equal than usual | 24 (9.3%) | 6.87 (5.35) | 7.41 (4.88) | 6.83 (3.67) | |||||||||

| Higher than usual | 214 (83.3%) | 11.68 (5.60) | 9.36 (5.42) | 7.87 (5.22) | |||||||||

| Speciality | ICU | 94 (36.6%) | 11.29 (5.72) | F | 0.462 | 0.764 | 8.65 (4.96) | 2.397 | 0.051 | 7.26 (5.51) | 0.948 | 0.437 | |

| Hospitalisation | 73 (28.4%) | 10.53 (5.94) | 8.86 (5.66) | 7.89 (5.06) | |||||||||

| Emergencies | 38 (14.8%) | 9.27 (6.32) | 7.50 (5.67) | 6.82 (4.63) | |||||||||

| Primary Care | 42 (16.3%) | 11.21 (5.71) | 10.90 (5.25) | 8.76 (4.84) | |||||||||

| Others | 10 (3.9%) | 10.20 (6.09) | 7.30 (5.74) | 7.10 (5.02) | |||||||||

| PPE availability | Yes | 107 (41.2%) | 9.46 (5.54) | t | 3.122 | 0.002 | 8.01 (4.76) | 2.056 | 0.041 | 6.77 (4.74) | 2.094 | 0.037 | |

| No | 150 (58.8%) | 11.77 (5.91) | 9.42 (5.78) | 8.17 (5.34) | |||||||||

| Worry | Yes | 195 (75.9%) | 11.81 (5.76) | t | −4.968 | <0.001 | 9.69 (5.21) | −4.563 | <0.001 | 8.11 (5.11) | −2.819 | 0.005 | |

| Psychological help | Yes | 51 (19.8%) | 13.08 (4.71) | t | −3.601 | 0.001 | 12.63 (5.35) | −5.921 | <0.001 | 9.14 (5.03) | −2.395 | 0.017 | |

| Social support | Total | 5.78 (1.21) | r2 | −0.227 | <0.001 | −0.098 | 0.117 | −0.151 | 0.016 | ||||

| Family | 5.88 (1.20) | r2 | −0.181 | 0.004 | −0.114 | 0.068 | −0.133 | 0.033 | |||||

| Friends | 5.64 (1.40) | r2 | −0.325 | <0.001 | −0.177 | 0.004 | −0.269 | <0.001 | |||||

| Significant Others | 5.81 (1.55) | r2 | −0.097 | 0.119 | −0.019 | 0.763 | −0.006 | 0.920 | |||||

| Resilience | 78.39 (14.29) | r2 | −0.269 | <0.001 | −0.242 | <0.001 | −0.230 | <0.001 | |||||

| Self-Efficacy | 29.18 (4.09) | r2 | −0.347 | <0.001 | −0.315 | <0.001 | −0.318 | <0.001 | |||||

| Cognitive Fusion | r2 | 0.539 | <0.001 | 21.97 (10.78) | 0.715 | <0.001 | 0.431 | <0.001 | |||||

| Student’s t Test for Paired Samples | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 1–2 | Time 1–3 | Time 2–3 | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t | p | t | p | t | p | |

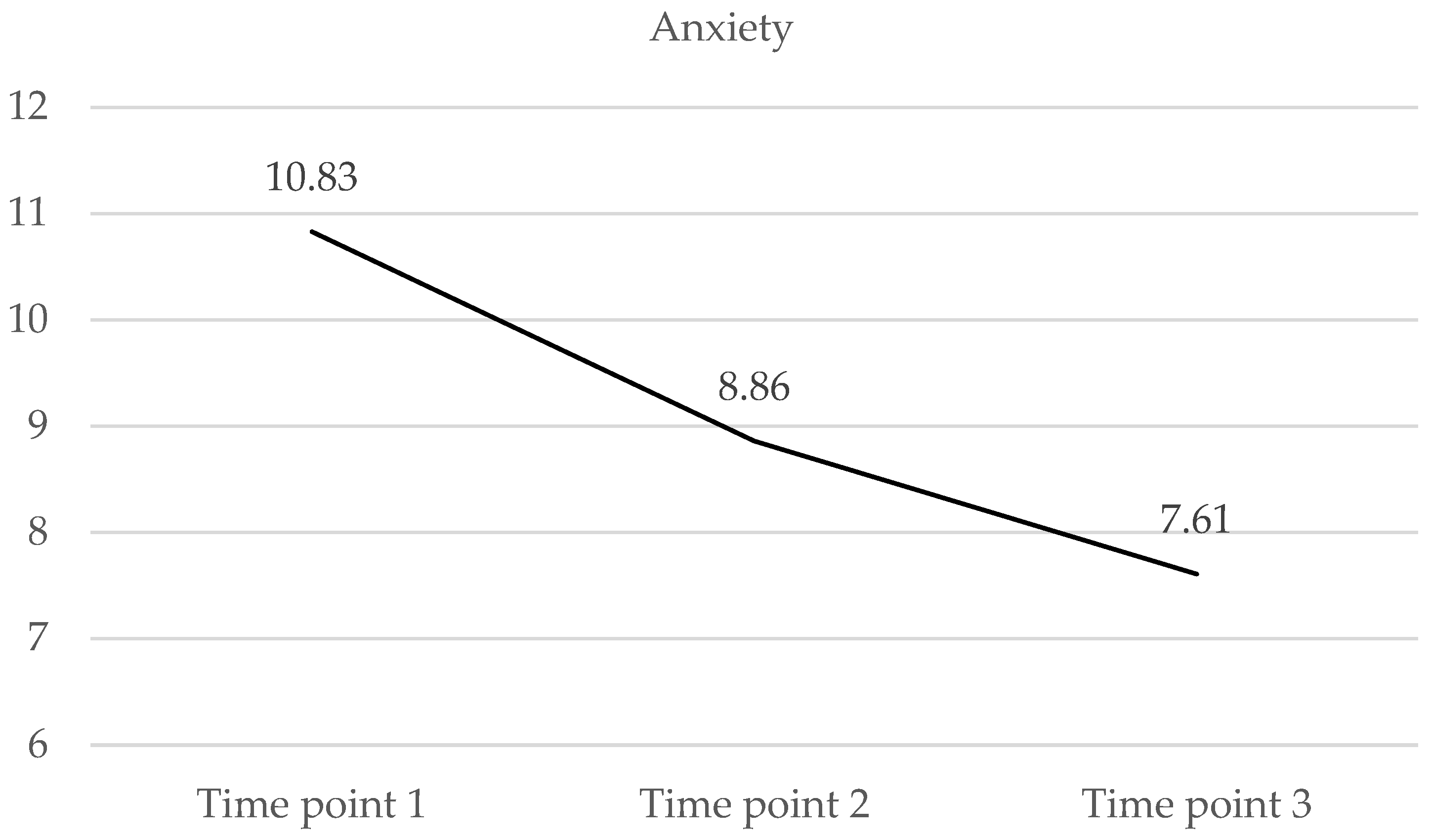

| Anxiety | 10.82 (5.86) | 8.86 (5.41) | 7.61 (5.13) | 6.694 | <0.001 | 10.377 | <0.001 | 3.879 | <0.001 |

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | ||

| Anxiety | 10.82 (5.86) | 8.86 (5.41) | 7.61 (5.13) | ||||

| Grouped Anxiety | No anxi/Min 2 | 41 (16.0) | 57 (22.2) | 74 (28.8) | |||

| Mild | 68 (26.5) | 94 (36.6) | 99 (38.5) | ||||

| Moderate | 78 (30.4) | 65 (25.3) | 64 (24.9) | ||||

| Severe | 70 (27.2) | 41 (16.0) | 20 (7.80) | ||||

| Anxiety Mode/Severe 1 | Yes | 148 (57.6) | 106 (41.2) | 84 (32.7) | |||

| Anxiety | F | R2 | IncR2 | Beta | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety T1 | 45,906 | 0.352 | 3.345 | |||

| Cognitive Fusion | 0.447 | 8.119 | <0.001 | |||

| –Social support friends | −0.200 | −3.811 | <0.001 | |||

| Self-efficacy | −0.134 | −2.416 | 0.016 | |||

| Anxiety T2 | 266,350 | 0.511 | 0.509 | |||

| Cognitive Fusion | 0.715 | 16.320 | <0.001 | |||

| Anxiety T3 | 23,504 | 0.272 | 0.260 | |||

| Cognitive Fusion | 0.307 | 5.188 | <0.001 | |||

| Social support friends | −0.299 | −4.333 | <0.001 | |||

| Social support significant others | 0.231 | 3.371 | 0.001 | |||

| Self- efficacy | −0.189 | −3.157 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gil-Almagro, F.; García-Hedrera, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C.; Carmona-Monge, F.J. Anxiety Evolution among Healthcare Workers—A Prospective Study Two Years after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic Including Occupational and Psychoemotional Variables. Medicina 2024, 60, 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081230

Gil-Almagro F, García-Hedrera FJ, Peñacoba-Puente C, Carmona-Monge FJ. Anxiety Evolution among Healthcare Workers—A Prospective Study Two Years after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic Including Occupational and Psychoemotional Variables. Medicina. 2024; 60(8):1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081230

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil-Almagro, Fernanda, Fernando José García-Hedrera, Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente, and Francisco Javier Carmona-Monge. 2024. "Anxiety Evolution among Healthcare Workers—A Prospective Study Two Years after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic Including Occupational and Psychoemotional Variables" Medicina 60, no. 8: 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081230

APA StyleGil-Almagro, F., García-Hedrera, F. J., Peñacoba-Puente, C., & Carmona-Monge, F. J. (2024). Anxiety Evolution among Healthcare Workers—A Prospective Study Two Years after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic Including Occupational and Psychoemotional Variables. Medicina, 60(8), 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081230