Coccygodynia in a Long-Term Cancer Survivor Diagnosed with Metastatic Cancer: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

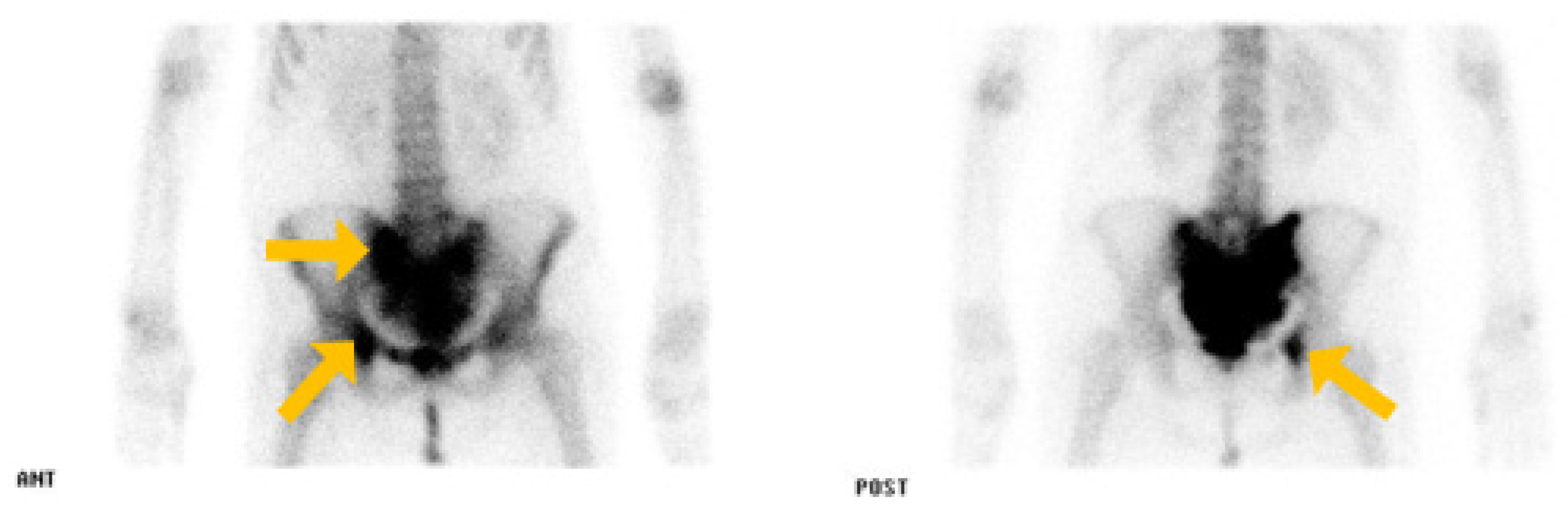

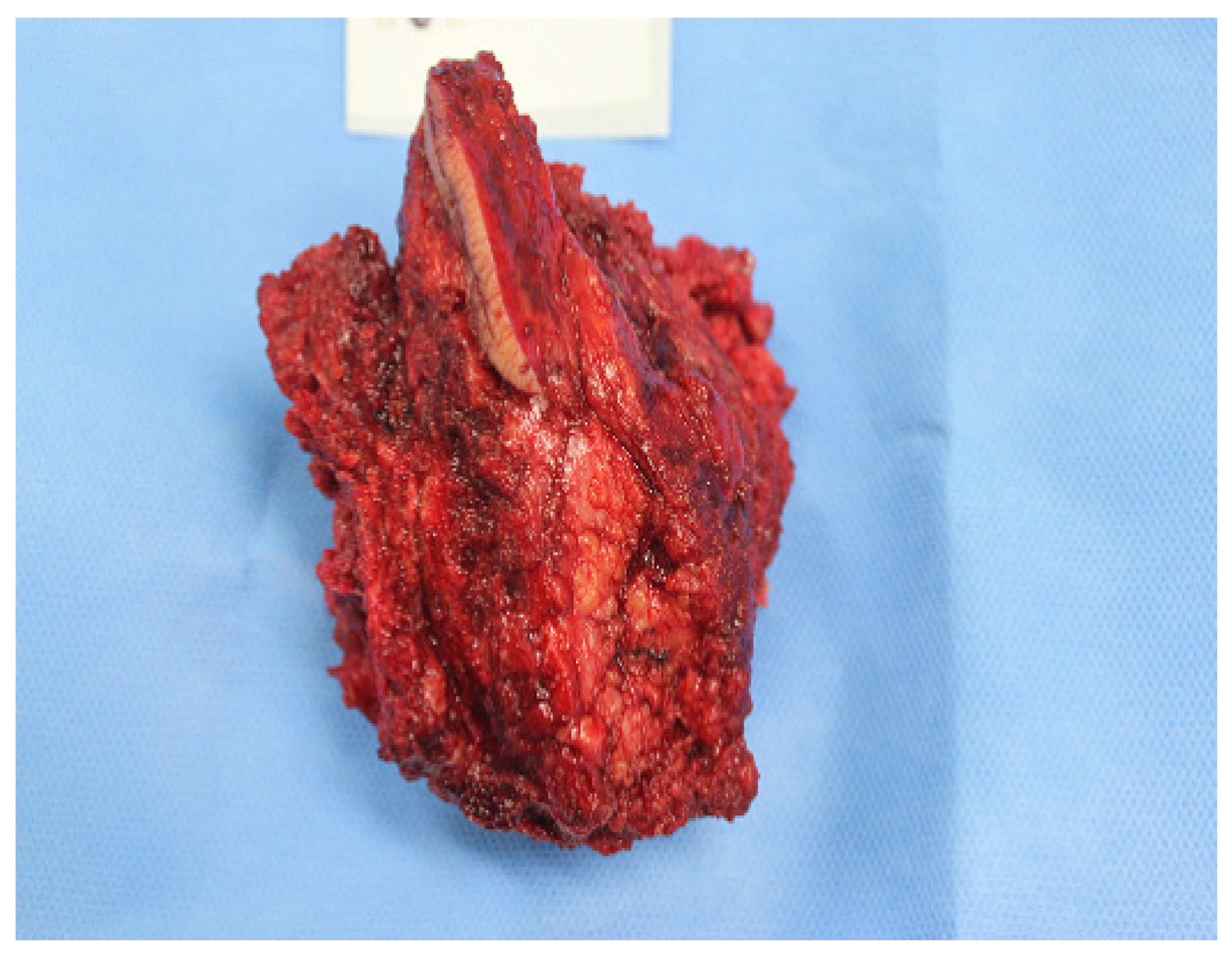

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riihimäki, M.; Hemminki, A.; Sundquist, J.; Hemminki, K. Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29765. [Google Scholar]

- Kanthan, R.; Loewy, J.; Kanthan, S.C. Skeletal metastases in colorectal carcinomas: A Saskatchewan profile. Dis. Colon Rectum 1999, 42, 1592–1597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lirette, L.S.; Chaiban, G.; Tolba, R.; Eissa, H. Coccydynia: An overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. Ochsner J. 2014, 14, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.S.; Lim, S.B.; Park, J.H.; Hong, Y.S. Recurrence in a Rectal Cancer Patient Who Underwent Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy Followed by Local Excision: A Case Report. Ann. Coloproctology 2021, 37, S24–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Nors, J.; Gotschalck, K.A.; Erichsen, R.; Andersen, C.L. Incidence of late recurrence and second primary cancers 5–10 years after non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 1890–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, M.; Las-Jankowska, M.; Rutkowski, A.; Bała, D.; Wiśniewski, D.; Tkaczyński, K.; Kowalski, W.; Głowacka-Mrotek, I.; Zegarski, W. Clinical Reality and Treatment for Local Recurrence of Rectal Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Medicina 2021, 57, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltse, L.L.; Fonseca, A.S.; Amster, J.; Dimartino, P.; Ravessoud, F.A. Relationship of the dura, Hofmann’s ligaments, Batson’s plexus, and a fibrovascular membrane lying on the posterior surface of the vertebral bodies and attaching to the deep layer of the posterior longitudinal ligament. An anatomical, radiologic, and clinical study. Spine 1993, 18, 1030–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Millan, M.; Merino, S.; Caro, A.; Feliu, F.; Escuder, J.; Francesch, T. Treatment of colorectal cancer in the elderly. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2015, 7, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glynne-Jones, R.; Wyrwicz, L.; Tiret, E.; Brown, G.; Rödel, C.; Cervantes, A.; Arnold, D. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, iv22–iv40. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, H.; Ishihara, S.; Kawai, K.; Nishikawa, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kiyomatsu, T.; Hata, K.; Nozawa, H.; Yamada, S.; Watanabe, T. Late sacral recurrence of rectal cancer treated by heavy ion radiotherapy: A case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2016, 2, 109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dampc, B.; Słowiński, K. Coccygodynia-pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. Review of the writing. Pol. J. Surg. 2017, 89, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Maigne, J.Y.; Doursounian, L.; Chatellier, G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: Role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine 2000, 25, 3072–3079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, S.; Cho, H.W.; Suh, J.-S.; Song, H.-T. Characteristic MRI findings of spinal metastases from various primary cancers: Retrospective study of pathologically-confirmed cases. J. Korean Soc. Magn. Reson. Med. 2013, 17, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kollender, Y.; Meller, I.; Bickets, J.; Flusser, G.; Issakov, J.; Merimsky, O.; Marouani, N.; Nirkin, A.; Weinbroum, A.A. Role of adjuvant cryosurgery in intralesional treatment of sacral tumors. Cancer 2003, 97, 2830–2838. [Google Scholar]

- Feldenzer, J.A.; McGauley, J.L.; McGillicuddy, J.E. Sacral and presacral tumors: Problems in diagnosis and management. Neurosurgery 1989, 25, 884–891. [Google Scholar]

- Quraishi, N.A.; Giannoulis, K.E.; Edwards, K.L.; Boszczyk, B.M. Management of metastatic sacral tumours. Eur. Spine J. 2012, 21, 1984–1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sciubba, D.M.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Diagnosis and management of metastatic spine disease. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 15, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, S.T.; Fisher, B.E.; Roberts, C.S. Coccydynia: A review of pathoanatomy, aetiology, treatment and outcome. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2010, 92, 1622. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, R.; Cheung, L.; Perry, P. Efficacy of fluoroscopically guided steroid injections in the management of coccydynia. Pain Physician 2007, 10, 775–778. [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz, O.H.; Sencan, S.; Kenis-Coskun, O. Pain Relief due to Transsacrococcygeal Ganglion Impar Block in Chronic Coccygodynia: A Pilot Study. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 1278–1281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marazano, E.; Trippa, F.; Chirico, L.; Basagni, M.L.; Rossi, R. Management of metastatic spinal cord compression. Tumori J. 2003, 89, 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Witham, T.F.; Khavkin, Y.A.; Gallia, G.L.; Wolinsky, J.-P.; Gokaslan, Z.L. Surgery insight: Current management of epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic spine disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2006, 2, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tomita, K.; Kawahara, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Yoshida, A.; Murakami, H.; Akamaru, T. Surgical strategy for spinal metastases. Spine 2001, 26, 298–306. [Google Scholar]

- Tokuhashi, Y.; Matsuzaki, H.; Oda, H.; Oshima, M.; Ryu, J. A revised scoring system for preoperative evaluation of metastatic spine tumor prognosis. Spine 2005, 30, 2186–2191. [Google Scholar]

- Ryuk, J.P.; Choi, G.-S.; Park, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Yoon, G.S.; Jun, S.H.; Kwon, Y.C. Predictive factors and the prognosis of recurrence of colorectal cancer within 2 years after curative resection. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2014, 86, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, D.; Park, J.H.; Kwon, S.Y. Coccygodynia in a Long-Term Cancer Survivor Diagnosed with Metastatic Cancer: A Case Report. Medicina 2024, 60, 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081365

Park JH, Park SJ, Kim D, Park JH, Kwon SY. Coccygodynia in a Long-Term Cancer Survivor Diagnosed with Metastatic Cancer: A Case Report. Medicina. 2024; 60(8):1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081365

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jung Hyun, Seong Jin Park, Dulee Kim, Jae Hoo Park, and So Young Kwon. 2024. "Coccygodynia in a Long-Term Cancer Survivor Diagnosed with Metastatic Cancer: A Case Report" Medicina 60, no. 8: 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081365

APA StylePark, J. H., Park, S. J., Kim, D., Park, J. H., & Kwon, S. Y. (2024). Coccygodynia in a Long-Term Cancer Survivor Diagnosed with Metastatic Cancer: A Case Report. Medicina, 60(8), 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina60081365