Abstract

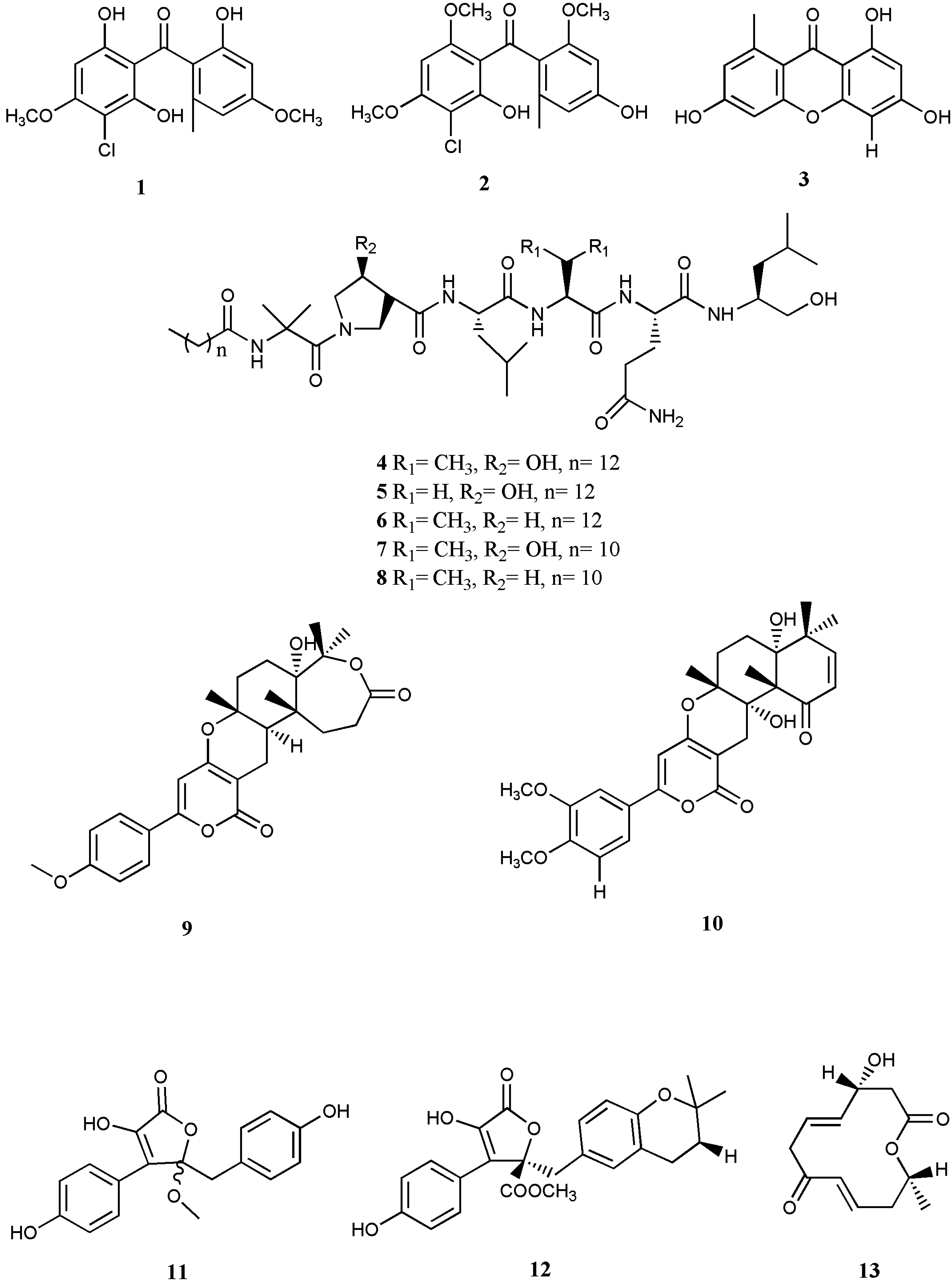

Biodiversity of the marine world is only partially subjected to detailed scientific scrutiny in comparison to terrestrial life. Life in the marine world depends heavily on marine fungi scavenging the oceans of lifeless plants and animals and entering them into the nutrient cycle by. Approximately 150 to 200 new compounds, including alkaloids, sesquiterpenes, polyketides, and aromatic compounds, are identified from marine fungi annually. In recent years, numerous investigations demonstrated the tremendous potential of marine fungi as a promising source to develop new antivirals against different important viruses, including herpes simplex viruses, the human immunodeficiency virus, and the influenza virus. Various genera of marine fungi such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, Cladosporium, and Fusarium were subjected to compound isolation and antiviral studies, which led to an illustration of the strong antiviral activity of a variety of marine fungi-derived compounds. The present review strives to summarize all available knowledge on active compounds isolated from marine fungi with antiviral activity.

1. Introduction

The marine world contains approximately one half of all species [1,2]. The vast expanse of the ocean and its unique environment are responsible for the exceptional chemical and biological diversity of marine organisms, with 300,000 described species and far more still to investigate [3]. The fact that less than 0.01%–0.1% of microbial species from the ocean are known to scientists highlights how effectively marine exploration can open up numerous avenues to marine organisms and their active chemical constituents [4]. Virtually all types of marine organisms, including algae, ascidians, bacteria, corals, fungi, and sponges, have come under scientific scrutiny for their natural products [5,6]. As a result of these studies, the ocean provides agrichemicals, cosmetics, enzymes, nutritional supplements, and pharmaceuticals, with great commercial prospects [7,8,9].

Historically, the pivotal role of fungi in different aspects of human life is very pronounced and this is true even in the marine world [10]. Marine fungi belong to the phyla Ascomycota, Bacidomycota, Chytridiomycota, Deuteromycota, and Zygomycota [11]. Evolution of these heterotrophic eukaryotes to degrade different solid substrates helps them to recycle dead plants (e.g., lignan and cellulose) and animal tissues (e.g., chitin and keratin) into the marine ecosystem through decomposition [10,12]. Investigations on marine fungi primarily commenced because of certain infections in the marine environment. Tolerance of some terrestrial species to the conditions of the marine ecosystem, including salt concentration, has made them potent pathogens in the marine world [13]. For instance, pathogenicity of genus Aspergilus and Fusarium solani contributed to the mortality of the Caribbean sea-fan and the infections of different marine crustaceans, respectively [14,15]. In addition, blue crabs, lobster eggs, and cultured crabs were reported to be infected by Lagenidium callinectes [16].

Despite the pathogenicity of certain marine fungi species, mutualistic interactions are the dominant types of relationship found in marine fungi [12]. The life of marine fungi heavily depends on their symbiotic relationships with other marine organisms such as algae and marine invertebrates [17]. For instance, Turgidosculum ulvae can only be grown in the thallus of Blidingia minima, a green algae [18]. Moreover, different Penicillium and Aspergillus species in the marine environment are isolated from sponges [19]. Isolation of these species requires the collection of the supporting material or host marine organism. Therefore, investigations on marine fungi confront the serious impediment of preserving samples until extraction [17].

As scientific interest has been sparked in marine microorganisms, fungi and their metabolites have begun to be recognized for their potent biological activities in the past few decades. Some of these metabolites give marine fungi the superiority to adapt to extreme habitats, compete for substrates, and ward off threats [20]. Moreover, fungi metabolites may be affected by their source of isolation, including sponges or other invertebrates, whose tissues they are harboring on or living in. Compounds isolated from marine fungi elicited promising assorted biological activities, especially anticancer and antidiabetic properties. However, other pharmaceutical activities have also reported, including cell cycle inhibition, kinase and phosphatase inhibition, antioxidant, neuritogenic, anti-inflammatory, antiplasmodial, and antiviral activities [12,21,22,23,24].

3. Conclusions

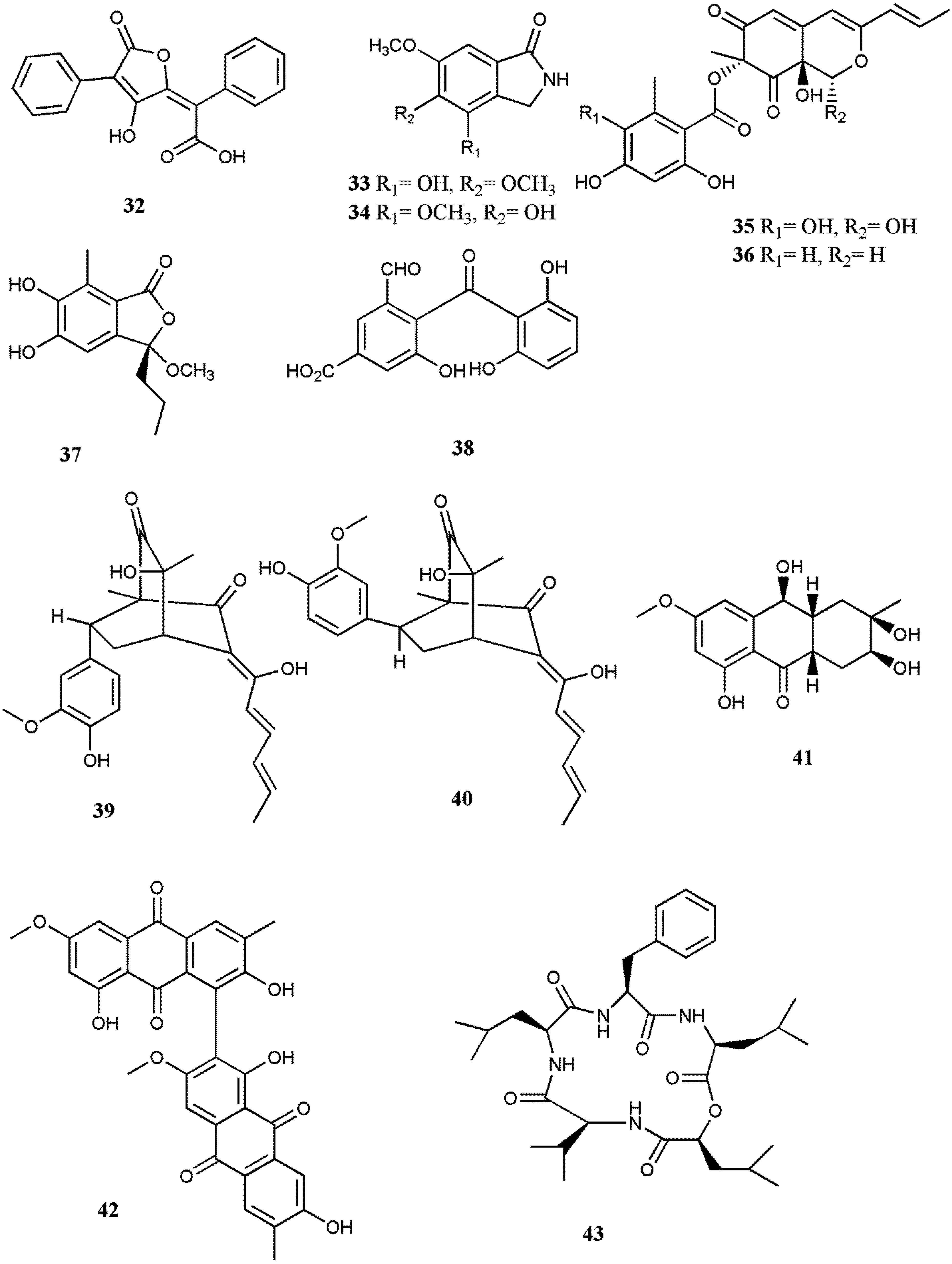

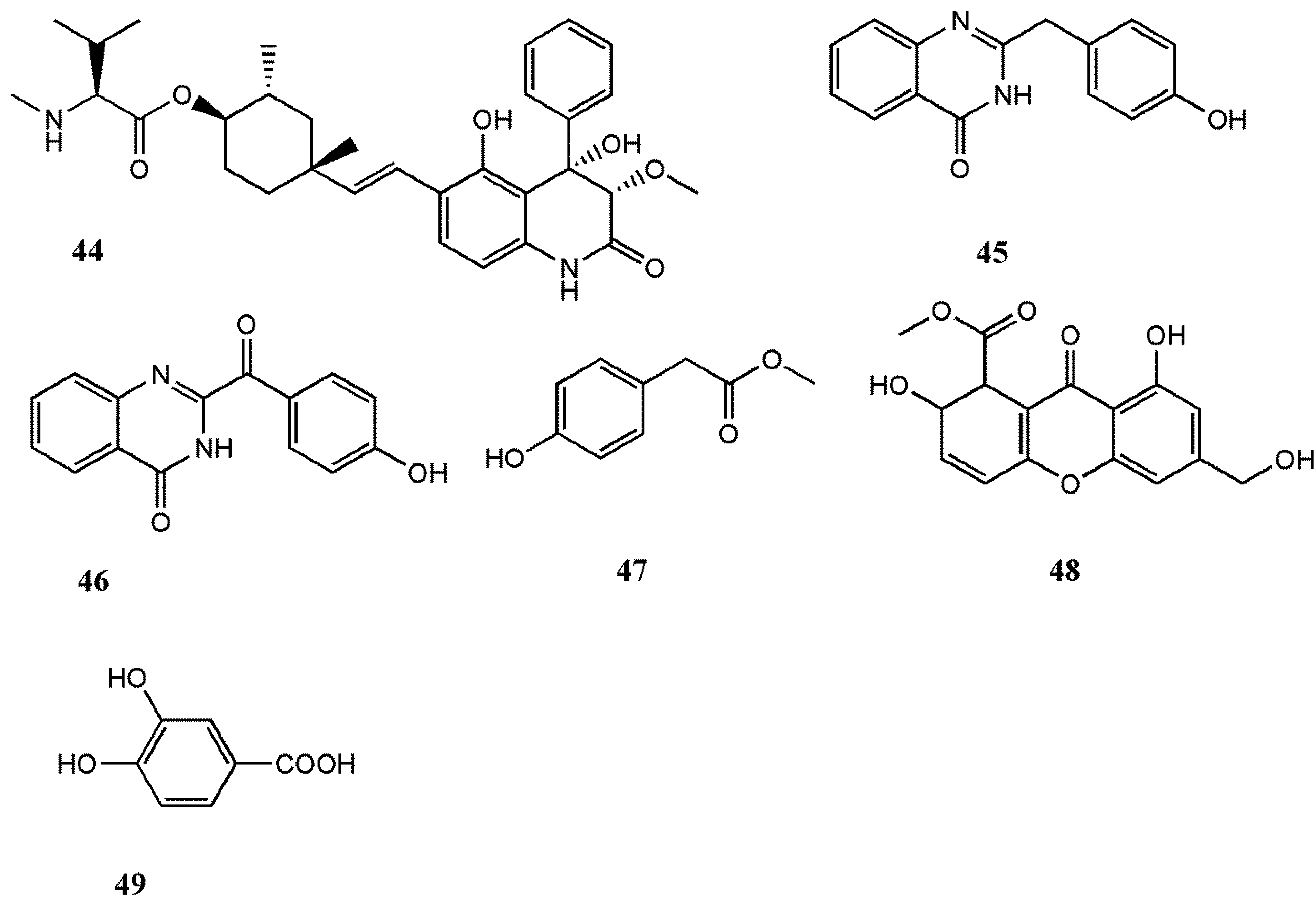

The increasing rate of viral resistance to antiviral drugs and drug toxicity is becoming a challenging problem in antiviral therapy. There are numerous reports on the resistance of different viruses to approved antiviral drugs [81,82,83]. However, there are many viral infections without any available effective treatment. Therefore, natural products from different living organisms including marine organisms could be potential candidates for development of new antiviral drugs. As we summarized in this review, there are different biomolecules from different chemical categories containing peptides, alkaloids, terpenoids, diacyglycerols, steroids, polysaccharides, and even more from different marine fungi with significant antiviral activities, as shown especially through in vitro studies [47,84,85]. Therefore, further investigation towards in vivo and even pharmacological studies for some of the abovementioned effective compounds seems to be crucial.

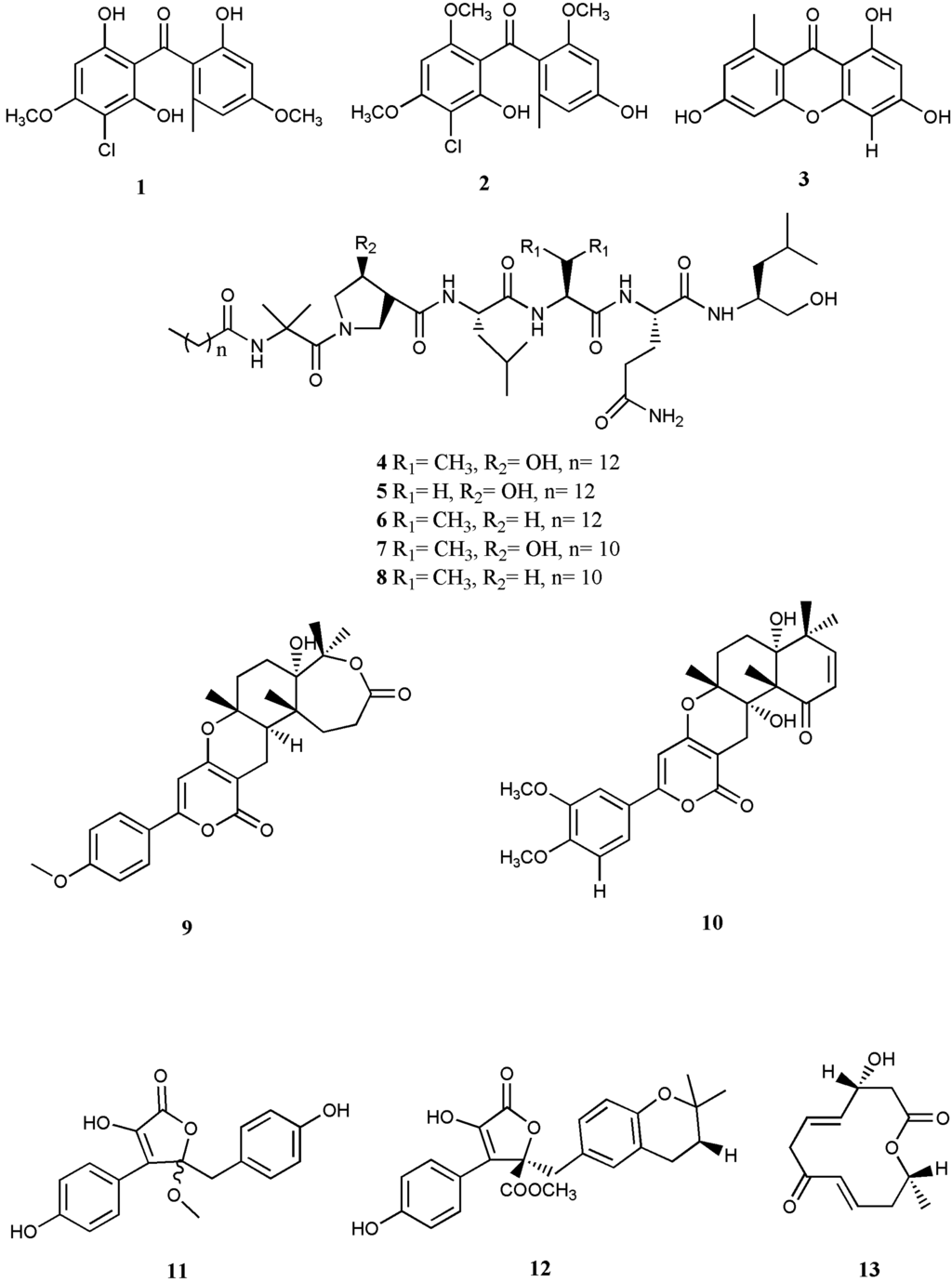

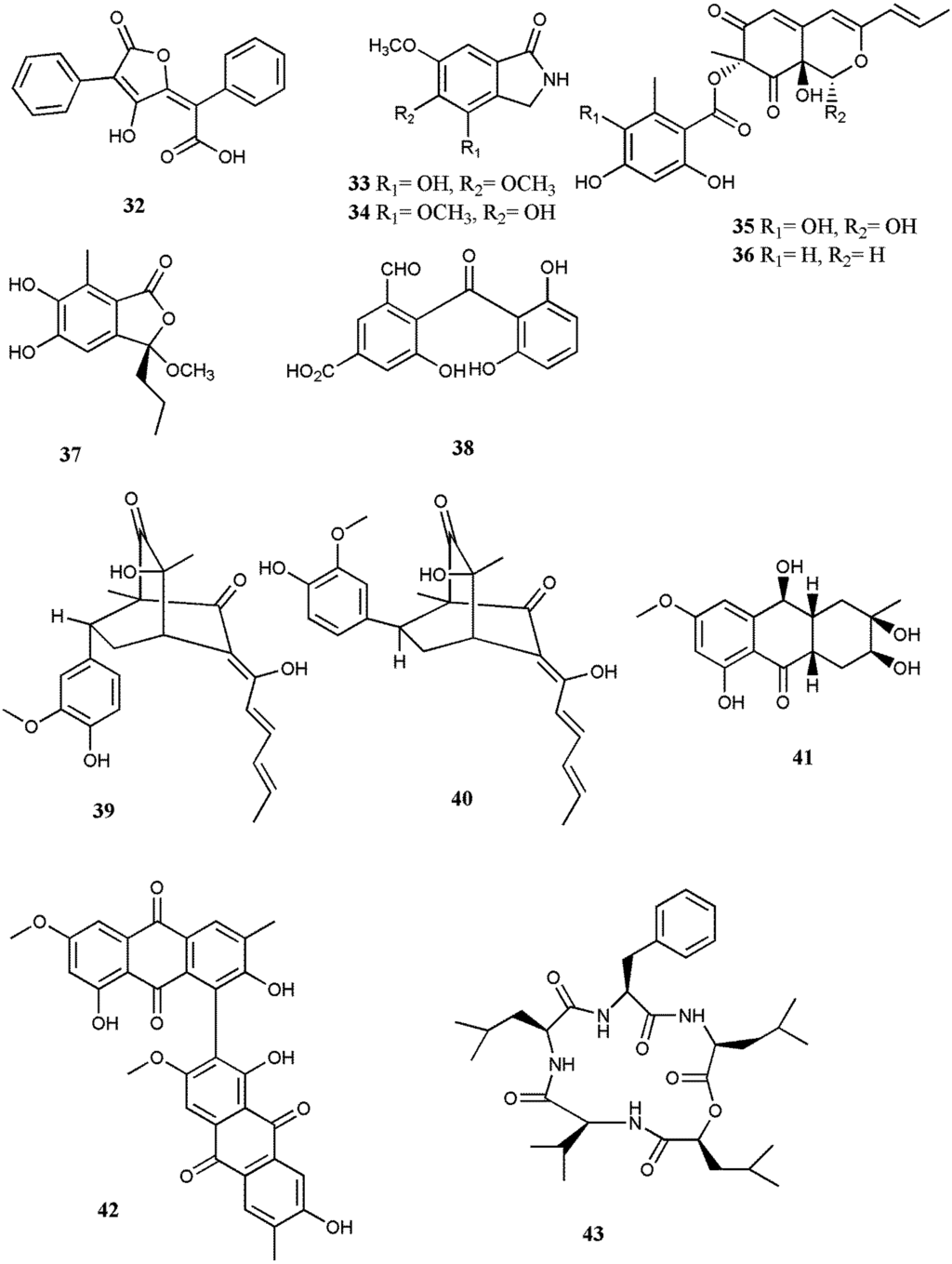

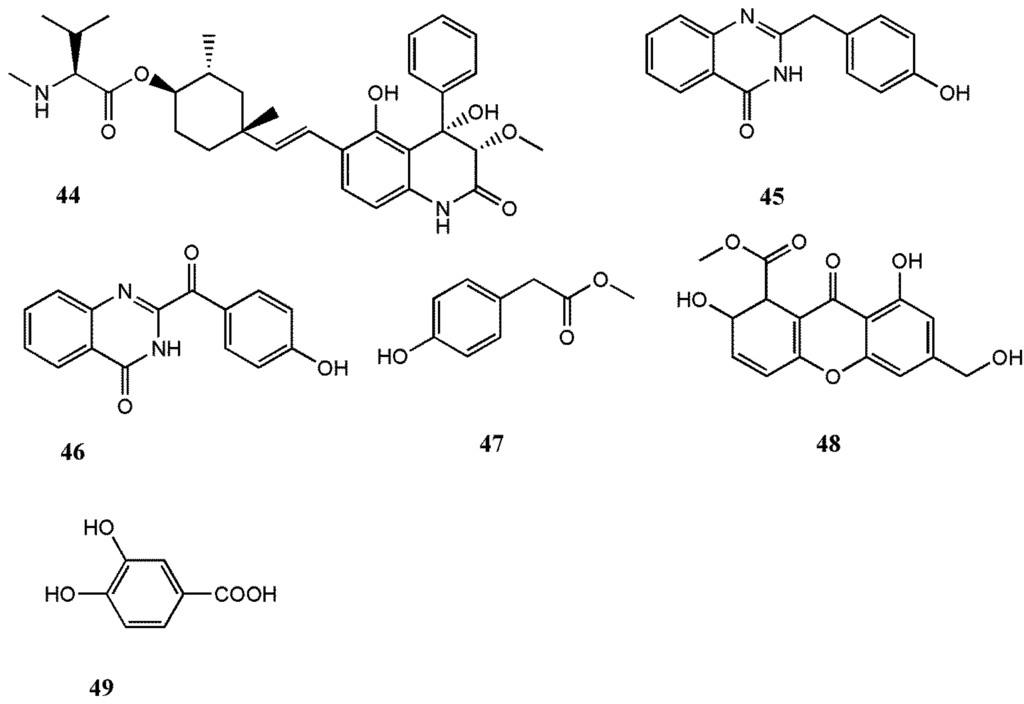

Organisms inhabiting the marine environment provide a diversity of bioactive compounds, which are exclusive as the aqueous habitat demands molecules with particular and vigorous biological compounds. Many scholars are devoted to investigating marine organisms to determine the development of potential biomolecules into therapeutic drugs and numerous compounds from marine fungi have been shown to possess notable antiviral activities. On the other hand, there are many important animal and human viruses yet to be studied, since for most viral diseases there has not been any effective therapeutic treatment available thus far. Therefore, infectious viruses with widespread prevalence, including EV71, HSV, HIV, MCV, and RSV, were used to examine the antiviral potential of the isolated compounds. Moreover, viruses responsible for important plant and animal infections, namely TMV and PRRS, were also employed in several studies. All together, the results showed quite noticeable cytotoxic effects against the respective viruses. From the preceding statement, we presented various compounds isolated from different marine fungi genera of which the most important ones exploited for their antiviral potential were Aspergillus sp., Penicillium sp., Cladosporium sp., Stachybotrys sp., and Neosartorya sp.; they are summarized in Table 1. Among these compounds, 13, a newly derived strain of Ascomycete, revealed marked inhibitory activity against HSV. Furthermore, 17 prompted a potent anti-influenza virus activity by showing a very low IC50 value (0.003 µM) and also oral administration of 17 in an in vivo study in PEG confirmed its significant antiviral activity. Furthermore, 44 exhibited a notable potency to elicit substantial antiviral activity against RSV. Nonetheless, the majority of the investigations were limited to basic screening and no mechanism of action was established for active compounds. It is pivotal for further research to characterize and determine the virus or host factors, which were targeted by antiviral compounds.

To develop antiviral drugs derived from marine fungi, in vivo and clinical studies are other aspects that should be exploited. The variety of the natural products from marine fungi evidently determines the potential for assigning some selected compounds to in vivo and probably clinical trials for forthcoming progress of anti-infective drugs. One of the considerable upcoming challenges will be the extensive production of these compounds to meet the demand for clinical trials and drug development. Several investigators believe that a specific form of combined genetic and metabolic engineering will be the potential resolution for commercial manufacture of these compounds [3]. It is hoped that this review could be a helpful source of guidance towards the discovery of new antiviral drugs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia, for High Impact Research (HIR) MOHE Grant (E000013-20001) and Long-Range Grant Scheme (LRGS) LR001/2011F. We also would like to thank University Malaya for UMRG fund (RG356-15AFR).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vo, T.-S.; Kim, S.-K. Potential anti-HIV agents from marine resources: An overview. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2871–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aneiros, A.; Garateix, A. Bioactive peptides from marine sources: Pharmacological properties and isolation procedures. J. Chromatogr. B 2004, 803, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadury, P.; Mohammad, B.T.; Wright, P.C. The current status of natural products from marine fungi and their potential as anti-infective agents. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 33, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, C.; Daniel, R. Metagenomic analyses: Past and future trends. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, D.J. Marine pharmacology. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2000, 77, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorofchian Moghadamtousi, S.; Karimian, H.; Khanabdali, R.; Razavi, M.; Firoozinia, M.; Zandi, K.; Abdul Kadir, H. Anticancer and antitumor potential of fucoidan and fucoxanthin, two main metabolites isolated from brown algae. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, D.J. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001, 18, 1R–49R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenical, W. New pharmaceuticals from marine organisms. Trends Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, G.M.; Wright, A.D.; Sticher, O.; Angerhofer, C.K.; Pezzuto, J.M. Biological activities of selected marine natural products. Planta Med. 1994, 60, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugni, T.S.; Ireland, C.M. Marine-derived fungi: A chemically and biologically diverse group of microorganisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornprobst, J.-M.; Ha, T.B.T. Encyclopedia of Marine Natural Products; Wiley-Blackwell: Weinheim, Germany, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, C. Forged in St. Anthony’s fire: Drugs for migraine. Mod. Drug Disc. 1999, 2, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tresner, H.; Hayes, J.A. Sodium chloride tolerance of terrestrial fungi. Appl. Microbiol. 1971, 22, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.W.; Ives, L.D.; Nagelkerken, I.A.; Ritchie, K.B. Caribbean sea-fan mortalities. Nature 1996, 383, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, D.; Polglase, J. Are fungal diseases significant in the marine environment? In The Biology of Marine Fungi; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, D. Mycoses of marine organisms: An overview of pathogenic fungi. In The Biology of Marine Fungi; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986; p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, K.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.; Freitas, A.C.; Duarte, A.C. Analytical techniques for discovery of bioactive compounds from marine fungi. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2012, 34, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Kohlmeyer, E. Marine Mycology: The Higher Fungi; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Blunt, J.W.; Copp, B.R.; Keyzers, R.A.; Munro, M.H.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 160–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, M.L.; Seldes, A.M.; Cabrera, G.M. Antibiotic long-chain and α, β-unsaturated aldehydes from the culture of the marine fungus Cladosporium sp. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Lateff, A.; Klemke, C.; König, G.M.; Wright, A.D. Two new xanthone derivatives from the algicolous marine fungus wardomyces anomalus. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daferner, M.; Anke, T.; Sterner, O. Zopfiellamides A and B, antimicrobial pyrrolidinone derivatives from the marine fungus Zopfiella latipes. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 7781–7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautschi, J.T.; Amagata, T.; Amagata, A.; Valeriote, F.A.; Mooberry, S.L.; Crews, P. Expanding the strategies in natural product studies of marine-derived fungi: A chemical investigation of Penicillium obtained from deep water sediment. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziveleka, L.-A.; Vagias, C.; Roussis, V. Natural products with anti-HIV activity from marine organisms. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003, 3, 1512–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Rao, Z. Current progress in antiviral strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantillo, C.; Ding, J.; Jacobo-Molina, A.; Nanni, R.G.; Boyer, P.L.; Hughes, S.H.; Pauwels, R.; Andries, K.; Janssen, P.A.; Arnold, E. Locations of anti-aids drug binding sites and resistance mutations in the three-dimensional structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: Implications for mechanisms of drug inhibition and resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 243, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morfin, F.; Thouvenot, D. Herpes simplex virus resistance to antiviral drugs. J. Clin. Virol. 2003, 26, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.; Boivin, G. Human cytomegalovirus resistance to antiviral drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taishi, T.; Takechi, S.; Mori, S. First total synthesis of (±)-stachyflin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 4347–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMinn, P.; Stratov, I.; Nagarajan, L.; Davis, S. Neurological manifestations of Enterovirus 71 infection in children during an outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Western Australia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 32, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Chang, L.-Y.; Hsia, S.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chiu, C.-H.; Hsueh, C.; Shih, S.-R.; Liu, C.-C.; Wu, M.-H. The 1998 Enterovirus 71 outbreak in Taiwan: Pathogenesis and management. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, S52–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.X.; Ng, M.M.-L.; Chu, J.J. Developments towards antiviral therapies against Enterovirus 71. Drug. Discov. Today 2010, 15, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Lin, X.; Lu, X.; Wan, J.; Zhou, X.; Liao, S.; Tu, Z.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y. Sesquiterpenoids and xanthones derivatives produced by sponge-derived fungus Stachybotry sp. HH1 ZSDS1F1-2. J. Antibiot. 2014, 68, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabenau, H.F.; Richter, M.; Doerr, H.W. Hand, foot and mouth disease: Seroprevalence of Coxsackie A16 and Enterovirus 71 in Germany. Med. Microbiol. Immun. 2010, 199, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, D.C.; Kelly, S.; Kauffman, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. Halovirs A–E, new antiviral agents from a marine-derived fungus of the genus Scytalidium. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 4263–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, X.-H.; Wang, Y.-F.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhou, M.-P.; Xu, X.-Y.; Qi, S.-H. Territrem and butyrolactone derivatives from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 6113–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shushni, M.A.; Singh, R.; Mentel, R.; Lindequist, U. Balticolid: A new 12-membered macrolide with antiviral activity from an Ascomycetous fungus of marine origin. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.B.; Zink, D.; Polishook, J.; Valentino, D.; Shafiee, A.; Silverman, K.; Felock, P.; Teran, A.; Vilella, D.; Hazuda, D.J. Structure and absolute stereochemistry of HIV-1 integrase inhibitor integric acid. A novel eremophilane sesquiterpenoid produced by a Xylaria sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 8775–8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, D.C.; Kelly, S.; Jensen, P.; Fenical, W. Synthesis and structure–activity relationships of the halovirs, antiviral natural products from a marine-derived fungus. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 4929–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minagawa, K.; Kouzuki, S.; Yoshimoto, J.; Kawamura, Y.; Tani, H.; Iwata, T.; Terui, Y.; Nakai, H.; Yagi, S.; Hattori, N. Stachyflin and acetylstachyflin, novel anti-influenza a virus substances, produced by Stachybotrys sp. RF-7260. I. Isolation, structure elucidation and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 2002, 55, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagi, S.; Ono, J.; Yoshimoto, J.; Sugita, K.-I.; Hattori, N.; Fujioka, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Sugimoto, H.; Hirano, K.; Hashimoto, N. Development of anti-influenza virus drugs I: Improvement of oral absorption and in vivo anti-influenza activity of stachyflin and its derivatives. Pharmaceut. Res. 1999, 16, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Lin, T.; Wang, W.; Xin, Z.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. Antiviral alkaloids produced by the mangrove-derived fungus Cladosporium sp. PJX-41. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Sun, X.; Yu, G.; Wang, W.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. Cladosins A–E, hybrid polyketides from a deep-sea-derived fungus, Cladosporium sphaerospermum. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-F.; Lin, X.-P.; Qin, C.; Liao, S.-R.; Wan, J.-T.; Zhang, T.-Y.; Liu, J.; Fredimoses, M.; Chen, H.; Yang, B. Antimicrobial and antiviral sesquiterpenoids from sponge-associated fungus, Aspergillus sydowii ZSDS1-F6. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Xin, Z.; Zhu, W. New rubrolides from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus OUCMDZ-1925. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Bao, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Tu, Z.-C.; Shi, Y.-M.; Qi, S.-H. Asperterrestide A, a cytotoxic cyclic tetrapeptide from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus SCSGAF0162. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Guo, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, D. Aspulvinones from a mangrove rhizosphere soil-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus GWQ-48 with anti-influenza a viral (H1N1) activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 1776–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, S.; Zhu, T.; Lin, Z.; Gu, J.; Li, D.; Gu, Q. Antiviral isoindolone derivatives from an endophytic fungus Emericella sp. Associated with Aegiceras corniculatum. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Fu, P.; Liu, P.; Zhu, W. Anti-influenza virus polyketides from the acid-tolerant fungus Penicillium purpurogenum JS03-21. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2014–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, X.; Du, L.; Wang, W.; Zhu, T.; Gu, Q.; Li, D. Sorbicatechols A and B, antiviral sorbicillinoids from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium chrysogenum PJX-17. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.-J.; Shao, C.-L.; Guo, Z.-Y.; Chen, J.-F.; Deng, D.-S.; Yang, K.-L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Fu, X.-M.; She, Z.-G.; Lin, Y.-C. Bioactive hydroanthraquinones and anthraquinone dimers from a soft coral-derived Alternaria sp. Fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.; Rowley, D.; Rhodes, D.; Gertsch, J.; Fenical, W.; Bushman, F. Mechanism of inhibition of a poxvirus topoisomerase by the marine natural product sansalvamide A. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999, 55, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prieto, C.; Castro, J.M. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in the boar: A review. Theriogenology 2005, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Li, W.; Wang, J. A novel and other bioactive secondary metabolites from a marine fungus Penicillium oxalicum 0312f1. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 2286–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Li, W.; Ouyang, M.A.; Wu, Z.; Lin, Q.; Xie, L. Identification of two marine fungi and evaluation of their antivirus and antitumor activities. Acta Microbiol. Sinic. 2009, 49, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Q.-W.; Ouyang, M.-A.; Shen, S.; Li, W. Bioactive metabolites from a marine-derived strain of the fungus Neosartorya fischeri. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 1402–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, R.J.; Roizman, B. Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet 2001, 357, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Manandhar, N.; Hudson, J.; Towers, G. Antiviral activities of nepalese medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1996, 52, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.L.; Conn, L.A.; Pinner, R.W. Trends in infectious disease mortality in the United States during the 20th century. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999, 281, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanters, S.; Mills, E.; Thorlund, K.; Bucher, H.; Ioannidis, J. Antiretroviral therapy for initial human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS treatment: Critical appraisal of the evidence from over 100 randomized trials and 400 systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sadr, W.M.; Holmes, C.B.; Mugyenyi, P.; Thirumurthy, H.; Ellerbrock, T.; Ferris, R.; Sanne, I.; Asiimwe, A.; Hirnschall, G.; Nkambule, R.N. Scale-up of HIV treatment through pepfar: A historic public health achievement. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012, 60, S96–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.B.; Blandford, J.M.; Sangrujee, N.; Stewart, S.R.; DuBois, A.; Smith, T.R.; Martin, J.C.; Gavaghan, A.; Ryan, C.A.; Goosby, E.P. Pepfar’s past and future efforts to cut costs, improve efficiency, and increase the impact of global HIV programs. Health Affairs 2012, 31, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazuda, D.; Blau, C.U.; Felock, P.; Hastings, J.; Pramanik, B.; Wolfe, A.; Bushman, F.; Farnet, C.; Goetz, M.; Williams, M. Isolation and characterization of novel human immunodeficiency virus integrase inhibitors from fungal metabolites. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 1999, 10, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.-N.; Lu, H.-Z.; Cao, B.; Du, B.; Shang, H.; Gan, J.-H.; Lu, S.-H.; Yang, Y.-D.; Fang, Q.; Shen, Y.-Z. Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza a (H7N9) virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2277–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pica, N.; Palese, P. Toward a universal influenza virus vaccine: Prospects and challenges. Annu. Rev. Med. 2013, 64, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalera, N.M.; Mossad, S.B. The first pandemic of the 21st century: A review of the 2009 pandemic variant influenza a (H1N1) virus. Postgrad. Med. 2009, 121, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellier, R. Review of aerosol transmission of influenza a virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Yoo, D. Cysteine residues of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus small envelope protein are non-essential for virus infectivity. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 3091–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, C.; Bøtner, A.; Takai, H.; Nielsen, J.P.; Jorsal, S. Experimental airborne transmission of PRRS virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2004, 99, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Anstey, A.V.; Bugert, J.J. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiferman, M.J.; Salabat, M.R.; Ujiki, M.B.; Strouch, M.J.; Cheon, E.C.; Silverman, R.B.; Bentrem, D.J. Sansalvamide induces pancreatic cancer growth arrest through changes in the cell cycle. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.H.; de Zwart-Steffe, R.T.; Donovan, B. Clinical and molecular aspects of Molluscum contagiosum infection in HIV-1 positive patients. Int. J. STD AIDS 1992, 3, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Falsey, A.R.; Walsh, E.E. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, S.A.; Hendry, R.M.; Beeler, J.A. Identification of a linear heparin binding domain for human respiratory syncytial virus attachment glycoprotein G. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 6610–6617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bos, L. Crop losses caused by viruses. Crop Prot. 1982, 1, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, A. The tobacco mosaic virus particle: Structure and assembly. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1999, 354, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creager, A.N.; Scholthof, K.-B.G.; Citovsky, V.; Scholthof, H.B. Tobacco mosaic virus: Pioneering research for a century. Plant Cell Online 1999, 11, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzenthaler, C. Resistance to plant viruses: Old issue, news answers? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.-H.; Chen, J.; Di, Y.-T.; Fang, X.; Dong, J.-H.; Sang, P.; Wang, Y.-H.; He, H.-P.; Zhang, Z.-K.; Hao, X.-J. Anti-tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) quassinoids from Brucea javanica (l.) Merr. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2010, 58, 1572–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megens, S.; Laethem, K.V. Antiretroviral therapy and drug resistance in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 infection. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2013, 11, 1159–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez-Arias, L.; Álvarez, M. Antiretroviral therapy and drug resistance in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 infection. Antiviral Res. 2014, 102, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, T.E.; Pikis, A.; Naeger, L.K.; Harrington, P.R. Resistance of human cytomegalovirus to ganciclovir/valganciclovir: A comprehensive review of putative resistance pathways. Antiviral Res. 2014, 101, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Fu, P.; Zhu, T.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W. Indole-diterpenoids with anti-H1N1 activity from the aciduric fungus Penicillium camemberti OUCMDZ-1492. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, K.-K.; Tang, X.-L.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, C.-L.; Zhang, X.-W.; Li, P.-L.; Li, G.-Q. Polyhydroxylated steroids from the south China sea soft coral Sarcophyton sp. And their cytotoxic and antiviral activities. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 4788–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).