An Umbrella Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Effectiveness of Interventions Aimed at Decreasing Food Prices to Increase Food Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

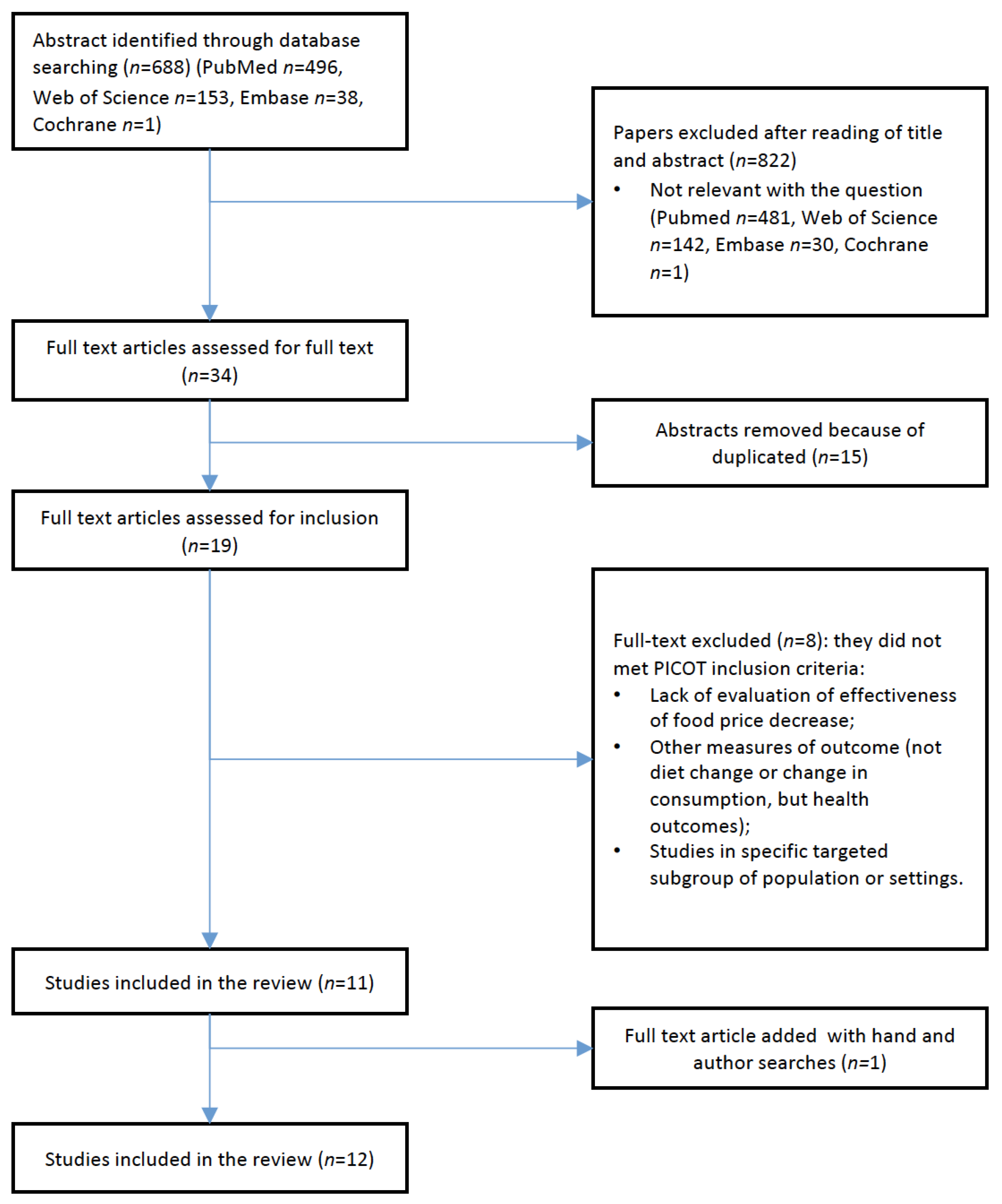

3. Search Results

3.1. Description of the Selected Studies

3.2. Findings

3.3. Quality Assessment of the Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Limits of the Studies Included in the Review

4.2. Limits of Our Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls, B.J.; Drewnowski, A.; Ledikwe, J.H. Changing the Energy Density of the Diet as a Strategy for Weight Management. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashby, S.; Kleve, S.; McKechnie, R.; Palermo, C. Measurement of the dimensions of food insecurity in developed countries: A systematic literature review. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2887–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, C.B. Measuring Food Insecurity. Science 2010, 327, 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Long, M.W.; Brownell, K.D. The impact of food prices on consumption: A systematic review of research on the price elasticity of demand for food. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capacci, S.; Mazzocchi, M.; Shankar, B.; Macias, J.B.; Verbeke, W.; Pérez-Cueto, F.J.; Kozioł-Kozakowska, A.; Piórecka, B.; Niedzwiedzka, B.; D’Addesa, D.; et al. Policies to promote healthy eating in Europe: A structured review of policies and their effectiveness. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hyseni, L.; Atkinson, M.; Bromley, H.; Orton, L.; Lloyd-Williams, F.; McGill, R.; Capewell, S. The effects of policy actions to improve population dietary patterns and prevent diet-related non-communicable diseases: Scoping review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 694–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Available online: www.handbook.cochrane.org (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Evidence. Quality Assessment Tool-Review Articles. Available online: https://www.healthevidence.org/documents/our-appraisal-tools/quality-assessment-tool-dictionary-en.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Thow, A.M.; Jan, S.; Leeder, S.; Swinburn, B. The effect of fiscal policy on diet, obesity and chronic disease: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010, 88, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, H.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Nghiem, N.; Blakely, T. Food pricing strategies, population diets, and non-communicable disease: A systematic review of simulation studies. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thow, A.M.; Downs, S.; Jan, S. A systematic review of the effectiveness of food taxes and subsidies to improve diets: Understanding the recent evidence. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niebylski, M.L.; Redburn, K.A.; Duhaney, T.; Campbell, N.R. Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition 2015, 31, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, J.; Mhurchu, C.N.; Blakely, T.; Rodgers, A.; Wilton, J. Effectiveness of monetary incentives in modifying dietary behavior: A review of randomized, controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2006, 64, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.P.; Brimblecombe, J.; Eyles, H.; Morris, P.; Vally, H.; O’Dea, K. Food subsidy programs and the health and nutritional status of disadvantaged families in high income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R. Effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: A review of field experiments. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, J.Q.; Gernes, R.; Stein, R.; Sherraden, M.S.; Knoblock-Hahn, A. A Systematic Review of Financial Incentives for Dietary Behavior Change. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Peñalvo, J.L.; Del Gobbo, L.; Silva, J.; Michaelson, M.; O’Flaherty, M.; Capewell, S.; Spiegelman, D.; Danaei, G.; Mozaffarian, D. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Trude, A.C.B.; Kim, H. Pricing Strategies to Encourage Availability, Purchase, and Consumption of Healthy Foods and Beverages: A Systematic Review. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, 170213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagiyawanna, A.; Townsend, N.; Mytton, O.; Scarborough, P.; Roberts, N.; Rayner, M. Studying the consumption and health outcomes of fiscal interventions (taxes and subsidies) on food and beverages in countries of different income classifications; a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier-Brown, F.C.; Summerbell, C.D.; Moore, H.J.; Routen, A.; Lake, A.A.; Adams, J.; White, M.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Abraham, C.; Adamson, A.J.; et al. The impact of interventions to promote healthier ready-to-eat meals (to eat in, to take away or to be delivered) sold by specific food outlets open to the general public: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, E.M.; Dernini, S.; Burlingame, B.; Meybeck, A.; Conforti, P. Review Article Food security and sustainability: Can one exist without the other? Public Health Nutr. 2017, 18, 2293–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Cooper, C.; Gunnell, D.; Haw, S.; Lawson, K.; Macintyre, S.; Ogilvie, D.; Petticrew, M.; Reeves, B.; Sutton, M.; et al. Using natural experiments to evaluate population health interventions: New Medical Research Council guidance. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Evidence, hierarchies, and typologies: Horses for courses. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, J. Evidence: Philosophy of science meets medicine. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhurst, J.O.; Abeysinghe, S. What Constitutes “Good” Evidence for Public Health and Social Policy-making? From Hierarchies to Appropriateness. Soc. Epistemol. 2016, 30, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, R.; An, R.; Segal, D.; Patel, D. A Cash-Back Rebate Program for Healthy Food Purchases in South Africa. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, R.; Patel, D.; Segal, D.; Sturm, R. Eating Better for Less: A National Discount Program for Healthy Food Purchases in South Africa. Am. J. Health Behav. 2013, 37, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Inclusion: healthy adult, general population. Exclusion: children, adolescents, unhealthy people. |

| Intervention | Inclusion: price decrease at the point of purchase (discounts, coupons, cash rebates) or other forms of incentives on healthy foods (fruit and vegetables and low-fat foods) purchasing and at restaurant, cafeterias Exclusion: other fiscal policies (taxes on energy-dense food high in saturated fat, trans fats, sugar and salt). |

| Comparison | Lack of intervention |

| Outcome | Inclusion: increase of purchase at point of sale, or of consumption of healthy food. Exclusion: health outcomes (weight loss, chronic disease…). |

| Study design | Inclusion: systematic reviews. |

| Search ID | Terms | N |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fiscal polic * | 173 |

| 2 | Tax | 13,643 |

| 3 | Public policy * OR tax (1 OR 2) | 54,441 |

| 4 | Subsid * | 22,371 |

| 5 | Fiscal polic* OR tax OR subsid * (3 OR 4) | 35,752 |

| 6 | Incentive | 204,512 |

| 7 | Fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive (5 OR 6) | 239,510 |

| 8 | Price OR pricing | 327,865 |

| 9 | Fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing (7 OR 8) | 556,367 |

| 10 | Voucher | 1069 |

| 11 | Fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid* OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher (9 OR 10) | 557,139 |

| 12 | “healthy diet” | 4394 |

| 13 | (fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher) AND (“healthy diet”) | 461 |

| 14 | Healthy diet | 31,806 |

| 15 | (fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher) AND (“healthy diet” OR healthy diet) | 1694 |

| 16 | "sustainable diet" | 61 |

| 17 | (fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher) AND (“healthy diet” OR healthy diet OR “sustainable diet”) | 29,452 |

| 18 | Sustainable diet | 1150 |

| 19 | (fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher) AND (“healthy diet” OR healthy diet OR “sustainable diet” OR sustainable diet) | 1698 |

| 20 | Healthy food pattern | 2430 |

| 21 | (fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher) AND (“healthy diet” OR healthy diet OR “sustainable diet” OR sustainable diet OR healthy food pattern) | 1818 |

| 22 | Food consumption | 101,450 |

| 23 | (fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher) AND (“healthy diet” OR healthy diet OR “sustainable diet” OR sustainable diet OR healthy food pattern OR food consumption) | 14,375 |

| 24 | (Meta-Analysis[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) | 366,291 |

| 25 | (fiscal polic * OR tax OR subsid * OR incentive OR price OR pricing OR voucher) AND (“healthy diet” OR healthy diet OR “sustainable diet” OR sustainable diet OR healthy food pattern OR food consumption) AND (Meta-Analysis[ptyp] OR systematic[sb]) | 496 |

| Author, Year | Number of Studies (Tot and Subsidies Only) | Databases | Population—Setting—Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thow, 2010 [16] | 24 studies (18 modelling studies, six empirical–ecological studies), four included (all are modelling studies) | Medline, ProQuest and Business Source Premier academic databases and Google Scholar. | Defiscalization (decrease of VAT) of fruit and veggy foods. |

| Eyles, 2012 [17] | 32 studies, 15 included (all are modelling studies; seven about subsidies, eight combinations of tax and subsidy) | Medline, Embase, and Food Science and Technology Abstracts between 1 January 1990 and 24 October 2011. | Subsidies on targeted foods (fruits and vegetables (F&V), soft drinks, F&V and fish, fibre) and on a range of healthier products and combination of tax and subsidy (total fat and/or saturated fat tax and a fibre/grain and/or fruit and vegetable subsidy). |

| Thow, 2014 [18] | 38 studies, 14 included: one RCT and 13 modelling studies | MEDLINE, Web of Knowledge, EconoLit, Business Source Premier academic databases and Google Scholar (the first 15 pages of each search using Google Scholar), between January 2009 and March 2012. | Subsidies (most in supermarket and in combination with taxes) on targeted foods or on a wide range of healthy foods. |

| Niebylski, 2015 [19] | 78 studies, 16 included: five modelling studies (two SR of modelling studies), three observational studies, (two SR), eight experimental studies. | PubMed, Medline and Cochrane Library databases (between June 2003 and November 2013) and Google Scholar (between June and November 2013) | Subsidies (most about discounts) in supermarkets on targeted food or “healthy food”, evaluating healthy food purchases (fruit and vegetables) and increased consumption. |

| Wall, 2006 [20] | Four RCT studies (about incentives), one included (three excluded because of setting—work or school setting, outcome –weight loss, population—obese adult) | MEDLINE (1966 to April 2005), EMBASE (1980 to 2005), CINAHL (1982 to April 2005), Cochrane Controlled Trials Register/Library (to 2005), and PsycINFO (1972 to April 2005) databases. | Coupon to purchase food at the farmer’s markets given to low-income women belonging to WIC programme. |

| Black, 2012 [21] | 14 studies, seven included: three RCTs, three CBAs and one ITS. (seven with different outcome: weight at birth, mother’s biomarkers and BMI…). | Medline, Cochrane, DARE, Embase, Cambridge Scientific Abstracts—Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts, Web of Science- Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation index, CINAHL, Informit-Health, Food Science and Technology Abstracts, and EconLit. Between 1980 and November 2010. | Subsidies alone or in combination with other intervention to socio-economic disadvantaged families, most in the WIC program (vouchers or discounts to a wide range of healthy food or only to fruit and vegetables or juice); the other about supermarket price discounts. |

| An, 2013 [22] | 20 studies, 15 included (seven7 RCTs, five CBAs, three cohort). (one in South Africa). | Cochrane Library, EconLit, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Web of Science | Subsidies (price discounts or vouchers) in Supermarkets and farmers’ markets (9), cafeterias (5) and restaurants (1), to adolescents or adults (metropolitan transit workers and low-income women), measuring both sales and self-report intake. |

| Purnell, 2014 [23] | 12 studies, two included (two quasi-experimental) (10 excluded because outcome is weight loss) | Vouchers to WIC low income women | |

| Afshin, 2017 [24] | 30 studies, 13 included: experimental studies (four RCTs, nine non-randomized) (seven excluded because about vending machines or school and work setting and BMI as outcome) | PubMed, Econlit, Embase, Ovid, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and CINAHL. | Cash back rebates, coupons and discounts at point of sale (supermarkets/markets), in communities and in restaurants/cafeterias. |

| Gittelsohn, 2017 [25] | 30 studies, 19 included: experimental studies (13 RCTs, six quasi-experimental). (11 excluded because about sub-group of population: workers, obese women with DM2, children at school or about taxes on unhealthy foods). | MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the Cochrane Library—from January 2000 through December 2016 (6 electronic databases). | Discounts, coupons/vouchers most to people of Food assistance programme and cash rebates at the point of sale and at all retailers in a |

| Alagiyawanna, 2015 [26] | 18 studies, only two included: 1 natural experiment and 1CBA | Medline (OvidSP) (1946-present), PubMed, EconLit and PAIS (Proquest), Global Health (OvidSP) [1973-present], Global Health Library. | Additional Vouchers to Post-partum low-income women of the WIC programme; reduction in soft drinks tax. |

| Hillier-Brown, 2017 [27] | 30 studies, three included: one cohort study, two CBAs (27 excluded because about other interventions) | ASSIA (ProQuest), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Embase (Ovid), MEDLINE (Ovid), NHS EED (Wiley Cochrane), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), from January 1993 to October 2015 | Redeemable coupons (alone and associated with health promotion in restaurants and fast food) in food outlets that sold “ready-to-eat” meals and are openly accessible to the general population to increase intake or purchases of healthy food. |

| Author | Conclusions | Limits | Health Evidence Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thow, 2010 [16] | Taxes and subsidies can influence consumption, particularly when they are large (at least 15% of product price). | High number of modelling studies, many of them about effect on targeted foods, not the overall diet. No experimental studies available. Empirical studies included had limited sensitivity. Narrative summaries. Conclusions not sufficient to establish a threshold of effectiveness, resulting in not sufficient information to implement a public policy. | 6 |

| Eyles, 2012 [17] | Price interventions are able to modify consumption. Price interventions have success in modifying consumption. There is a linear relationship between the value of the subsidy and the increase of fruit and vegetables consumption, i.e., 1% of decrease in the F&V price increase purchase of the same food-group of 0,35%. Eight modelling studies evaluate the association of taxes and subsidies: major evidence of success with a risk of compensatory purchasing. | All studies are modelling studies. Low quality of studies included (27/32): heterogeneity in model used and value of the subsidy. Lack of evidence in low-income countries. Only four studies estimated a health benefit for lower socio–economic population compared to high, even if the majority of these studies (11/14) estimated that fiscal policies would result in absolute improvements in dietary outcomes for low-income. | 9 * |

| Thow, 2014 [18] | Strong evidence from robust modelling studies and from one RCT of taxes and subsidies combined, even if there is evidence that subsidies can increase caloric intake. Threshold from which success is observed is 10–20% (in one study a price decrease of only 1.8% resulted effective) of the food price. The bigger the amount of the subsidy (or of the combination of interventions), the bigger the positive effect (from 2–5% to 25%). | Inclusion of different type of studies allows assessing strength and limits in producing results of all the different studies. Heterogeneity of population group studied made the conclusion uncertain. | 6 |

| Niebilski, 2015 [19] | Consistent moderately strong evidence of success, concluding the support to the implementation of interventions population-wide. Modelling studies: maximum success in association of taxes and subsidies of a minimum of 10–15% of the food price. Association with fiscal policies with other actions (food education or marketing actions) enhance the success. | Many results based on modelling studies and price elasticity rather than field works. Most experimental studies are localized and not demographically representative. No engaging of food industry in their will of implementing the actions with the need to engage many stakeholders in the design of an action within the entire population. | 7 |

| Wall, 2006 [20] | Positive effect on both food purchase and weight loss: incentives that decrease price at the point of sale are more effective in modify consumers’ choices than individual interventions (such as coupons). | Results are not sufficient to assess how to implement the interventions population-wide. Only four RCTs included. Short duration (max 18 months). Follow-up only in one study. Lack of cost-effectiveness measures and impact on food industry. Lack of evaluating the effect in different subgroup of population (ethnicity, SES…). | 8 |

| Black, 2012 [21] | Success of intervention but in limited high-quality studies. Modelling studies: female participants of the WIC program in USA demonstrated a 10–20% increase in targeted nutrients and foods due to the subsidy program. Studies about other actions showed similar improvements in nutrient intake, biomarkers or food purchases. The targeted F&V subsidies with nutrition education were able to increase F&V intake by 1–2 serves/day in women. RCT: supermarket price discount of 12.5% significantly increased purchases of total, F&V and healthier food after 6 months. | Quality of evidence is limited because of the risk of selection bias and residual confounding as possible explanations of the success in the 10 non-randomised studies. Limited evidence of success In adults and children. Much of the dietary intake data comes from self-report (imprecision). Follow-up is present in all studies, but in only two success is maintained significantly at the end of the follow-up period: only two studies reported on follow-up post-intervention and after subsidies of six months duration and 12 months and found persistence of effect. Lack of definition of the optimal duration of the intervention. | 9 |

| An, 2013 [22] | Evidence of success in 19/20 studies. Level of subsidies varies from 10% to 50% and voucher’s value ranges 7.50$ and 50$ (except for an intervention in which voucher’s value is 0.50$). The comparison between interventions’ results are neither agree with each other, nor exhaustive. | Use of small sample/convenience sample, in specific targeted setting, short time and often no follow-up (in seven it is present, but the results are not maintained). Lack of cost-effectiveness analysis and evaluation of the impact on food industry. Lack of analysis of the impact on the whole diet pattern and not only on targeted foods. Poor evidence of the impact on different population subgroup (ethnicity, SES…). | 5 |

| Purnell, 2014 [23] | Subsidies show a short-term positive effect on diet pattern: change is not maintained after a follow-up period. | Heterogeneity of studies (setting, population, methods) makes comparison difficult. | 5 |

| Afshin, 2017 [24] | Evidence of success (class I, level of evidence A, AHA evidence grading system). A 10% price decrease increases the consumption of the targeted food of 12%, of the food groups –fruits and vegetables of 14% and of other foods of 16%. The association of taxes and subsidies increases the positive effect. | Most outcomes are evaluated through a self-questionnaire (less strong than objective sales’ measure). | 8 |

| Gittelsohn, 2017 [25] | Evidence of success. Intervention’s impact at retail level is an increased sale of targeted healthy foods (from 15% to 1000%; increased purchases in eight), of stocking (from 40% to 63%; increased consumption in 13). Three studies found no effect on healthy foods purchase and consumption. | No strong indication to affirm that one type of intervention is better than another is. All seemed to be effective. | 10 * |

| Alagiyawanna, 2015 [26] | Evidence of success with limits. In CBA: statistically significant evidence of success between subsidies and both F&V and other healthy foods intake in HICs. Effects after 6mo of follow-up. In natural experiment: 20% reduction in soft drinks tax determined 6.8% increase in average consumption. | Lack of RCTs. Use of self-reported information about diet change: bias and errors. | 8 * |

| Hillier-Brown, 2017 [27] | Weak to moderate evidence of effectiveness, in increasing purchase of healthy food (three about incentives). | Low quality evidence with few high-quality designs. Impact seems to be insignificant. Limited generalizability of the results because data come from specific fast food chains within USA, and no info at food outlet level and on consumption. Lack of information about change in consumption, only about purchases. Lack of cost-effectiveness evidence reported. | 10 * |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milani, C.; Lorini, C.; Baldasseroni, A.; Dellisanti, C.; Bonaccorsi, G. An Umbrella Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Effectiveness of Interventions Aimed at Decreasing Food Prices to Increase Food Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132346

Milani C, Lorini C, Baldasseroni A, Dellisanti C, Bonaccorsi G. An Umbrella Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Effectiveness of Interventions Aimed at Decreasing Food Prices to Increase Food Quality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(13):2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132346

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilani, Chiara, Chiara Lorini, Alberto Baldasseroni, Claudia Dellisanti, and Guglielmo Bonaccorsi. 2019. "An Umbrella Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Effectiveness of Interventions Aimed at Decreasing Food Prices to Increase Food Quality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 13: 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132346

APA StyleMilani, C., Lorini, C., Baldasseroni, A., Dellisanti, C., & Bonaccorsi, G. (2019). An Umbrella Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Effectiveness of Interventions Aimed at Decreasing Food Prices to Increase Food Quality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132346