Smoking-Related DNA Methylation is Associated with DNA Methylation Phenotypic Age Acceleration: The Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

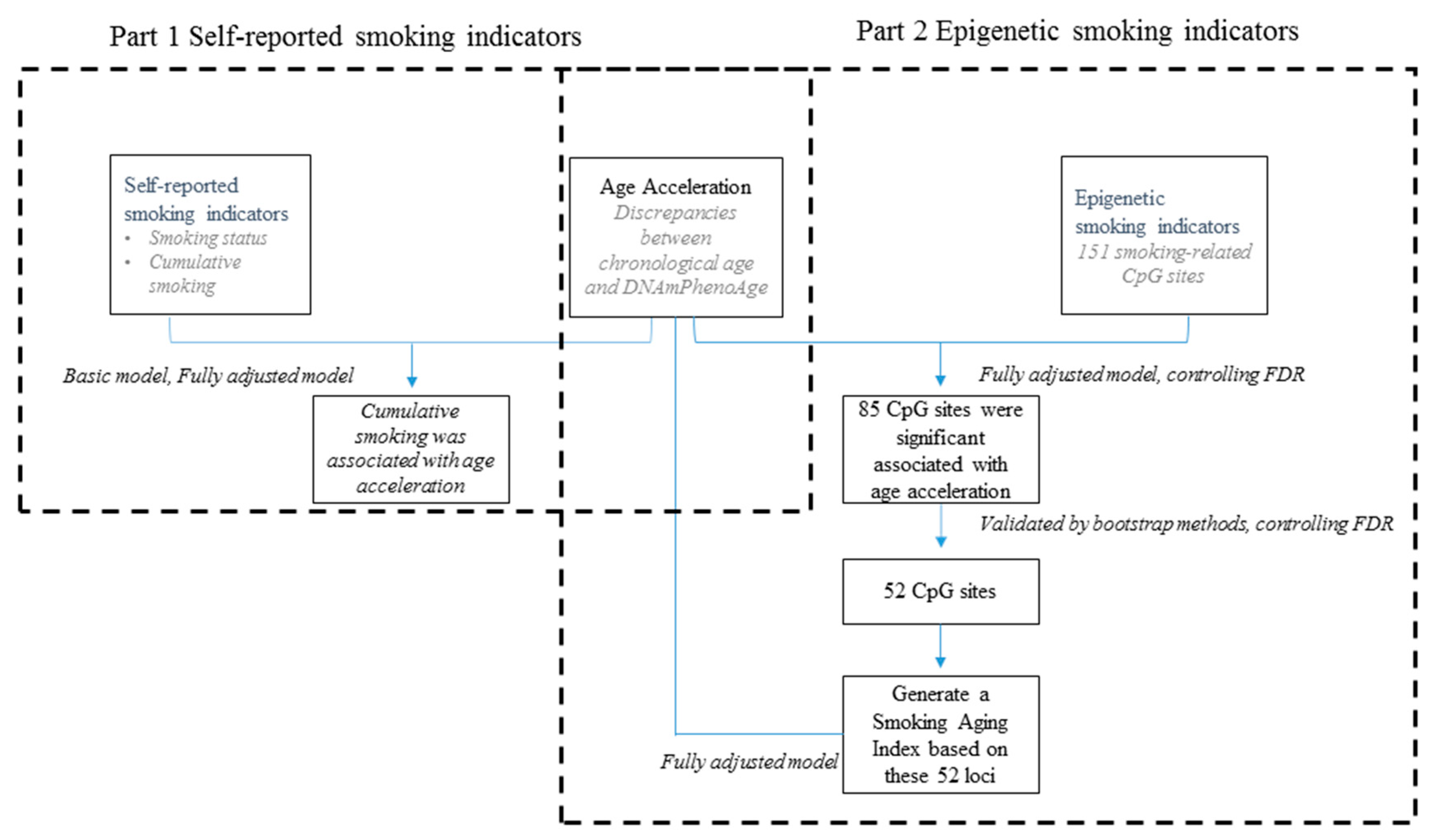

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

2.2. DNA Methylation Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

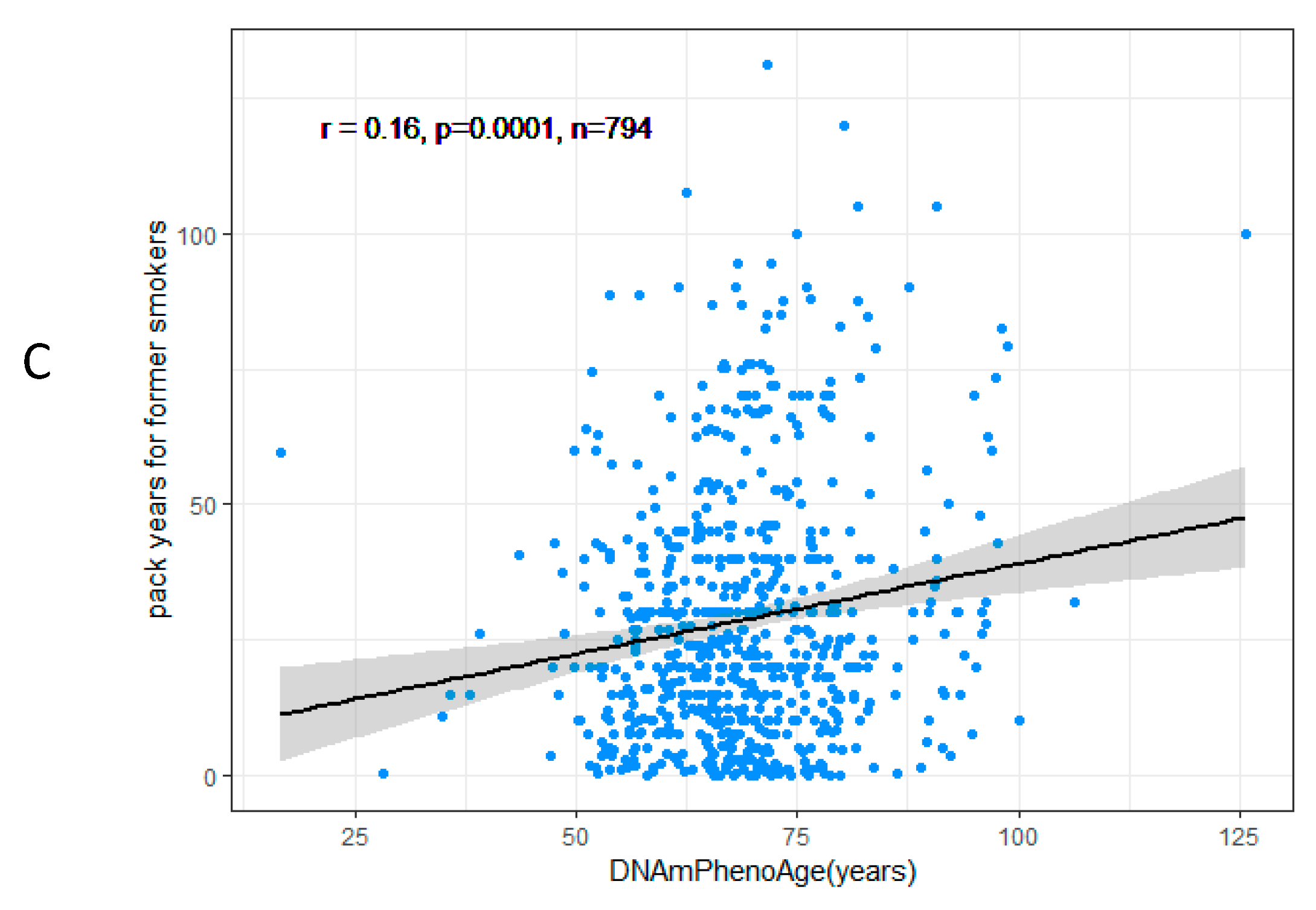

3.2. DNAmPhenoAge Acceleration and Smoking Indicators

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, K.W.; Pausova, Z. Cigarette smoking and DNA methylation. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bakulski, K.M.; Fallin, M.D. Epigenetic epidemiology: promises for public health research. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2014, 55, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Jia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Breitling, L.P.; Brenner, H. DNA methylation changes of whole blood cells in response to active smoking exposure in adults: a systematic review of DNA methylation studies. Clin. Epigenetics 2015, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Schöttker, B.; Florath, I.; Stock, C.; Butterbach, K.; Holleczek, B.; Mons, U.; Brenner, H. Smoking-associated DNA methylation biomarkers and their predictive value for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 124, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Yang, Z.; Wong, A.; Pipinikas, C.P.; Jiao, Y.; Jones, A.; Anjum, S.; Hardy, R.; Salvesen, H.B.; Thirlwell, C. Correlation of smoking-associated DNA methylation changes in buccal cells with DNA methylation changes in epithelial cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, H.R.; Tillin, T.; McArdle, W.L.; Ho, K.; Duggirala, A.; Frayling, T.M.; Smith, G.D.; Hughes, A.D.; Chaturvedi, N.; Relton, C.L. Differences in smoking associated DNA methylation patterns in South Asians and Europeans. Clin. Epigenetics 2014, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, C.I.; Lin, Q.; Koch, C.M.; Eisele, L.; Beier, F.; Ziegler, P.; Bauerschlag, D.O.; Jöckel, K.-H.; Erbel, R.; Mühleisen, T.W. Aging of blood can be tracked by DNA methylation changes at just three CpG sites. Genome Boil. 2014, 15, R24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, G.; Guinney, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Hughes, G.; Sadda, S.; Klotzle, B.; Bibikova, M.; Fan, J.-B.; Gao, Y. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Boil. 2013, 14, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2018, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E. Modeling the rate of senescence: can estimated biological age predict mortality more accurately than chronological age? J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 68, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsky, D.W.; Caspi, A.; Houts, R.; Cohen, H.J.; Corcoran, D.L.; Danese, A.; Harrington, H.; Israel, S.; Levine, M.E.; Schaefer, J.D. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E4104–E4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ostro, B.; Hu, J.; Goldberg, D.; Reynolds, P.; Hertz, A.; Bernstein, L.; Kleeman, M.J. Associations of mortality with long-term exposures to fine and ultrafine particles, species and sources: results from the California Teachers Study Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastiani, P.; Thyagarajan, B.; Sun, F.; Schupf, N.; Newman, A.B.; Montano, M.; Perls, T.T. Biomarker signatures of aging. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrucci, L.; Hesdorffer, C.; Bandinelli, S.; Simonsick, E.M. Frailty as a nexus between the biology of aging, environmental conditions and clinical geriatrics. Public Health Rev. 2010, 32, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.; Rose, C.L.; Damon, A. The Veterans Administration longitudinal study of healthy aging. Gerontologist 1966, 6, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseman, E.A.; Accomando, W.P.; Koestler, D.C.; Christensen, B.C.; Marsit, C.J.; Nelson, H.H.; Wiencke, J.K.; Kelsey, K.T. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitling, L.P.; Salzmann, K.; Rothenbacher, D.; Burwinkel, B.; Brenner, H. Smoking, F2RL3 methylation, and prognosis in stable coronary heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2841–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benayoun, B.A.; Pollina, E.A.; Brunet, A. Epigenetic regulation of ageing: linking environmental inputs to genomic stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Boil. 2015, 16, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Breitling, L.P.; Brenner, H. Relationship of tobacco smoking and smoking-related DNA methylation with epigenetic age acceleration. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 46878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, S.R.; Dogan, M.V.; Lei, M.K.; Cutrona, C.E.; Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Simons, R.L.; Brody, G.H.; Philibert, R.A. Methylomic aging as a window onto the influence of lifestyle: tobacco and alcohol use alter the rate of biological aging. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 2519–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philibert, R.A.; Beach, S.R.; Lei, M.-K.; Brody, G.H. Changes in DNA methylation at the aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor may be a new biomarker for smoking. Clin. Epigenetics 2013, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeilinger, S.; Kühnel, B.; Klopp, N.; Baurecht, H.; Kleinschmidt, A.; Gieger, C.; Weidinger, S.; Lattka, E.; Adamski, J.; Peters, A. Tobacco smoking leads to extensive genome-wide changes in DNA methylation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monick, M.M.; Beach, S.R.; Plume, J.; Sears, R.; Gerrard, M.; Brody, G.H.; Philibert, R.A. Coordinated changes in AHRR methylation in lymphoblasts and pulmonary macrophages from smokers. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2012, 159, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, M.; Abrahams, B.S.; Stone, J.L.; Duvall, J.A.; Perederiy, J.V.; Bomar, J.M.; Sebat, J.; Wigler, M.; Martin, C.L.; Ledbetter, D.H. Linkage, association, and gene-expression analyses identify CNTNAP2 as an autism-susceptibility gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 82, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Li, T.; Pan, Y.; Tao, H.; Ju, K.; Wen, Z.; Fu, Y.; An, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, T. CNTNAP2 is significantly associated with schizophrenia and major depression in the Han Chinese population. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 207, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Vrijenhoek, T.; Markx, S.; Janssen, I.; Van Der Vliet, W.; Faas, B.; Knoers, N.; Cahn, W.; Kahn, R.; Edelmann, L. CNTNAP2 gene dosage variation is associated with schizophrenia and epilepsy. Mol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Miyake, K.; Horikawa, Y.; Hara, K.; Osawa, H.; Furuta, H.; Hirota, Y.; Mori, H.; Jonsson, A.; Sato, Y. Variants in KCNQ1 are associated with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.C.; Draper, M.P.; Lipko, M.; Dabrowski, M. Gng12 is a novel negative regulator of LPS-induced inflammation in the microglial cell line BV-2. Inflamm. Res. 2010, 59, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wu, G.; Wen, J.; Luo, X.; Huang, H. preparation of rabbit anti-rat Lrrn3 polyclonal antibody and study of its expression****⋆. Neural Regen. Res. 2010, 5, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Oshima, M.; Endoh, M.; Endo, T.A.; Toyoda, T.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Sugiyama, F.; Koseki, H.; Kyba, M.; Iwama, A.; Osawa, M. Genome-wide analysis of target genes regulated by HoxB4 in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells developing from embryonic stem cells. Blood 2011, 117, e142–e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kelada, S.N.; Eaton, D.L.; Wang, S.S.; Rothman, N.R.; Khoury, M.J. The role of genetic polymorphisms in environmental health. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autrup, H. Genetic polymorphisms in human xenobiotica metabolizing enzymes as susceptibility factors in toxic response. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2000, 464, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.J.; Goodman, S.J.; Kobor, M.S. DNA methylation and healthy human aging. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, A.; Dogan, M.; Beach, S.; Philibert, R. Current and future prospects for epigenetic biomarkers of substance use disorders. Genes 2015, 6, 991–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd-Acosta, C.; Fallin, M.D. The role of epigenetics in genetic and environmental epidemiology. Epigenomics 2016, 8, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martino, D.; Loke, Y.J.; Gordon, L.; Ollikainen, M.; Cruickshank, M.N.; Saffery, R.; Craig, J.M. Longitudinal, genome-scale analysis of DNA methylation in twins from birth to 18 months of age reveals rapid epigenetic change in early life and pair-specific effects of discordance. Genome Boil. 2013, 14, R42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenker, N.S.; Polidoro, S.; van Veldhoven, K.; Sacerdote, C.; Ricceri, F.; Birrell, M.A.; Belvisi, M.G.; Brown, R.; Vineis, P.; Flanagan, J.M. Epigenome-wide association study in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Turin) identifies novel genetic loci associated with smoking. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 22, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Besingi, W.; Johansson, Å. Smoke-related DNA methylation changes in the etiology of human disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 23, 2290–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | All Visits | First Visit | Second Visit | Third Visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of measures | 1214 | 692 | 418 | 104 |

| Chronological age (years) | 74.3 (7.0) | 72.7 (6.7) | 76.3 (6.8) | 79.8 (6.0) |

| DNAmPhenoAge (years) | 70.5 (12.9) | 68.4 (11.9) | 70.6 (12.2) | 83.6 (13.9) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | 374 (31%) | 207 (30%) | 131 (31%) | 36 (35%) |

| Current smoker | 46 (4%) | 29 (4%) | 15 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Former smoker | 794 (65%) | 456 (66%) | 272 (65%) | 66 (63%) |

| Total years of smoking cigarettes (years) | 16.7 (15.8) | 16.9 (15.7) | 16.4 (15.9) | 11.3 (15.5) |

| Alcohol consumption (g/d) | ||||

| Abstainer | 230 (24%) | 146 (24%) | 81 (25%) | 3 (25%) |

| Low (0–40 g/d) | 652 (69%) | 420 (69%) | 223 (70%) | 9 (75%) |

| Intermediate (40–60 g/d) | 37 (4%) | 26 (4%) | 11 (3%) | 0 |

| High (≥60 g/d) | 23(2%) | 18 (3%) | 5 (2%) | 0 |

| Physical activity (MET-hours/week) | ||||

| Low(≤12 kcal/kg hours/week) | 667 (64%) | 408 (63%) | 240 (65%) | 19 (58%) |

| Median (12–30 kcal/kg hours/week) | 227 (22%) | 139 (22%) | 83 (23%) | 5 (15%) |

| High (≥30 kcal/kg hours/week) | 152 (15%) | 98 (15%) | 45 (12%) | 9 (27%) |

| Years of education | ||||

| ≤12 years | 335 (33%) | 215 (33%) | 115 (33%) | 5 (42%) |

| 13–16 years | 477 (47%) | 314 (48%) | 159 (46%) | 4 (33%) |

| >16 years | 209 (20%) | 131 (20%) | 75 (21%) | 3 (25%) |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Underweight or normal weight (<25.0) | 265 (22%) | 139 (20%) | 94 (22%) | 32 (31%) |

| Overweight (≥25.0 to <30.0) | 636 (52%) | 374 (54%) | 214 (51%) | 48 (46%) |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 313 (26%) | 179 (26%) | 110 (26%) | 24 (23%) |

| Chronic diseases | ||||

| Hypertension | 731 (71%) | 464 (70%) | 258 (73%) | 9 (75%) |

| Stroke | 99 (8%) | 53 (8%) | 39 (9%) | 7 (7%) |

| Coronary heart disease | 397 (33%) | 208 (30%) | 146 (35%) | 43 (41%) |

| Diabetes | 193(16%) | 99 (14%) | 73 (17%) | 21 (20%) |

| Smoking Indicator | Model 1 a | Model 2 b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking Status | Estimate # | SE * | P-Value | Estimate # | SE | P-Value |

| Current smoker | 3.41 | 1.83 | 0.06 | 2.69 | 1.86 | 0.15 |

| Former smoker | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.79 | 0.82 |

| Never smoker | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Cumulative smoking (pack-year) | 0.06 | 0.01 | 3.4 e-5 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.003 |

| Chr | CpG Site | Gene | Effect Size per SD (SE) # | P-Value | FDR- Adjusted P-Value | P-Value for Bootstrap | FDR-Adjusted P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | cg25189904 | GNG12 | 1.21 | 6.7E−04 | 2.0E−03 | 1.1E−02 | 2.7E−02 |

| cg04885881 | 1.91 | 3.5E−08 | 4.0E−07 | 2.7E−08 | 3.0E−07 | ||

| cg11314684 | AKT3 | 1.82 | 4.3E−08 | 4.6E−07 | 2.0E−03 | 7.7E−03 | |

| cg09662411 | GFI1 | −1.66 | 2.5E−06 | 1.9E−05 | 5.0E−03 | 1.6E−02 | |

| cg10399789 | GFI1 | 1.58 | 4.5E−06 | 3.0E−05 | 1.7E−02 | 3.3E−02 | |

| cg12547807 | 2.35 | 1.8E−14 | 6.9E−13 | 1.1E−13 | 4.3E−12 | ||

| cg19713429 | CAPZB | 1.89 | 6.6E−09 | 8.3E−08 | 1.0E−03 | 4.5E−03 | |

| cg21140898 | −1.61 | 7.1E−06 | 4.1E−05 | 4.3E−06 | 1.3E−05 | ||

| cg26764244 | GNG12 | 2.01 | 3.1E−09 | 4.4E−08 | 2.0E−03 | 7.7E−03 | |

| cg27537125 | 2.82 | 1.1E−19 | 1.6E−17 | 5.3E−18 | 1.3E−16 | ||

| 2 | cg01940273 | −1.40 | 2.7E−04 | 9.2E−04 | 1.3E−02 | 2.9E−02 | |

| cg03329539 | 1.71 | 2.7E−07 | 2.5E−06 | 1.6E−02 | 3.2E−02 | ||

| cg23079012 | −1.05 | 9.8E−04 | 2.6E−03 | 1.5E−02 | 3.0E−02 | ||

| 3 | cg18642234 | GPX1 | 1.86 | 2.9E−06 | 2.1E−05 | 1.4E−05 | 1.7E−04 |

| cg18754985 | CLDND1 | −1.13 | 1.6E−04 | 5.9E−04 | 3.0E−03 | 1.1E−02 | |

| 4 | cg24556382 | GALNT7 | 1.40 | 3.7E−05 | 1.7E−04 | 7.0E−03 | 2.0E−02 |

| 5 | cg14817490 | AHRR | 1.85 | 2.6E−07 | 2.5E−06 | 1.5E−06 | 3.8E−05 |

| cg05575921 | AHRR | −0.97 | 1.3E−05 | 1.2E−04 | 7.0E−03 | 2.0E−02 | |

| cg25648203 | AHRR | −1.14 | 6.6E−04 | 2.0E−03 | 2.2E−02 | 4.0E−02 | |

| cg26703534 | AHRR | −1.54 | 1.6E−05 | 7.7E−05 | 1.5E−02 | 3.0E−02 | |

| cg01899089 | AHRR | 1.53 | 6.9E−06 | 4.1E−05 | 4.9E−05 | 1.2E−05 | |

| cg01097768 | AHRR | 2.50 | 3.4E−12 | 6.3E−11 | 2.1E−11 | 4.5E−10 | |

| cg11554391 | AHRR | 1.72 | 3.2E−06 | 2.2E−05 | 2.0E−03 | 7.7E−03 | |

| cg17924476 | AHRR | 1.55 | 4.9E−06 | 3.1E−05 | 3.0E−03 | 1.1E−02 | |

| 6 | cg24859433 | −1.44 | 5.8E−05 | 2.4E−04 | 1.5E−02 | 3.0E−02 | |

| cg14753356 | 1.65 | 5.1E−04 | 1.6E−03 | 1.2E−02 | 2.8E−02 | ||

| cg15474579 | CDKN1A | 1.68 | 1.0E−05 | 5.5E−05 | 2.7E−02 | 4.7E−02 | |

| cg20778199 | −3.01 | 5.7E−17 | 4.3E−15 | 3.6E−16 | 2.7E−14 | ||

| 7 | cg11207515 | CNTNAP2 | 1.72 | 5.0E−07 | 4.3E−06 | 5.0E−03 | 1.6E−02 |

| cg25949550 | CNTNAP2 | 2.56 | 8.7E−14 | 2.2E−12 | 6.0E−13 | 1.4E−11 | |

| cg05221370 | LRRN3 | 2.43 | 6.6E−12 | 1.1E−10 | 4.9E−11 | 4.3E−09 | |

| cg07826859 | MYO1G | 1.64 | 4.6E−05 | 2.0E−04 | 2.8E−02 | 4.8E−02 | |

| cg09837977 | LRRN3 | 1.92 | 1.6E−05 | 7.7E−05 | 9.0E−03 | 2.4E−02 | |

| 8 | cg25305703 | 1.39 | 6.7E−05 | 2.7E−04 | 1.3E−02 | 2.9E−02 | |

| 10 | cg25953130 | ARID5B | −1.54 | 1.5E−05 | 7.6E−05 | 7.0E−03 | 2.0E−02 |

| 11 | cg23771366 | PRSS23 | 1.31 | 8.1E−04 | 2.4E−03 | 1.5E−02 | 3.0E−02 |

| cg04039799 | NAV2 | 1.85 | 3.2E−09 | 4.4E−08 | 1.4E−08 | 3.9E−07 | |

| cg16556677 | KCNQ1 | −1.41 | 2.2E−04 | 7.7E−04 | 8.0E−03 | 2.2E−02 | |

| cg16611234 | 1.36 | 1.7E−04 | 5.9E−04 | 7.0E−03 | 2.0E−02 | ||

| 12 | cg02583484 | HNRNPA1 | 1.22 | 3.5E−04 | 1.2E−03 | 2.0E−02 | 3.8E−02 |

| cg04158018 | NFE2 | −1.38 | 1.1E−04 | 4.0E−04 | 4.0E−03 | 1.4E−02 | |

| 13 | cg23681440 | 1.17 | 8.9E−04 | 2.5E−03 | 2.4E−02 | 4.3E−02 | |

| 14 | cg13976502 | C14orf43 | 1.22 | 1.5E−05 | 7.6E−05 | 1.0E−03 | 4.5E−03 |

| cg22851561 | C14orf43 | 2.49 | 1.0E−15 | 5.2E−14 | 3.7E−14 | 6.4E−13 | |

| cg13038618 | 1.20 | 1.1E−03 | 2.9E−03 | 2.9E−02 | 4.8E−02 | ||

| 16 | cg06972908 | ITGAL | 2.64 | 2.5E−14 | 7.7E−13 | 9.3E−12 | 4.6E−10 |

| cg13500388 | CBFB | 1.67 | 1.7E−05 | 7.7E−05 | 1.1E−02 | 2.7E−02 | |

| cg16794579 | XYLT1 | 2.37 | 6.7E−13 | 1.4E−11 | 3.5E−12 | 6.9E−10 | |

| 17 | cg19572487 | RARA | 1.43 | 7.2E−05 | 2.8E−04 | 2.2E−02 | 4.0E−02 |

| cg07465627 | STXBP4 | 1.46 | 1.8E−06 | 1.4E−05 | 6.2E−05 | 7.1E−04 | |

| 19 | cg15187398 | MOBKL2A | 1.84 | 5.1E−07 | 4.3E−06 | 4.2E−06 | 1.8E−05 |

| cg23973524 | CRTC1 | −1.63 | 7.4E−06 | 4.1E−05 | 1.0E−02 | 2.6E−02 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Gao, X.; Just, A.C.; Colicino, E.; Wang, C.; Coull, B.A.; Hou, L.; Zheng, Y.; Vokonas, P.; Schwartz, J.; et al. Smoking-Related DNA Methylation is Associated with DNA Methylation Phenotypic Age Acceleration: The Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132356

Yang Y, Gao X, Just AC, Colicino E, Wang C, Coull BA, Hou L, Zheng Y, Vokonas P, Schwartz J, et al. Smoking-Related DNA Methylation is Associated with DNA Methylation Phenotypic Age Acceleration: The Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(13):2356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132356

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yang, Xu Gao, Allan C. Just, Elena Colicino, Cuicui Wang, Brent A. Coull, Lifang Hou, Yinan Zheng, Pantel Vokonas, Joel Schwartz, and et al. 2019. "Smoking-Related DNA Methylation is Associated with DNA Methylation Phenotypic Age Acceleration: The Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 13: 2356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132356

APA StyleYang, Y., Gao, X., Just, A. C., Colicino, E., Wang, C., Coull, B. A., Hou, L., Zheng, Y., Vokonas, P., Schwartz, J., & Baccarelli, A. A. (2019). Smoking-Related DNA Methylation is Associated with DNA Methylation Phenotypic Age Acceleration: The Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2356. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132356