Usability Testing of a Mobile Health Intervention to Address Acute Care Needs after Sexual Assault

Abstract

:1. Addressing Barriers to Acute Care after Sexual Assault: Usability of a Mobile Health Intervention

1.1. Barriers to Follow-Up Healthcare after a SAMFE

1.2. mHealth as a Viable Solution to Address Key Barriers

1.3. Previous Research on Technology-Based Interventions in This Population

1.4. Current Study

2. Methods

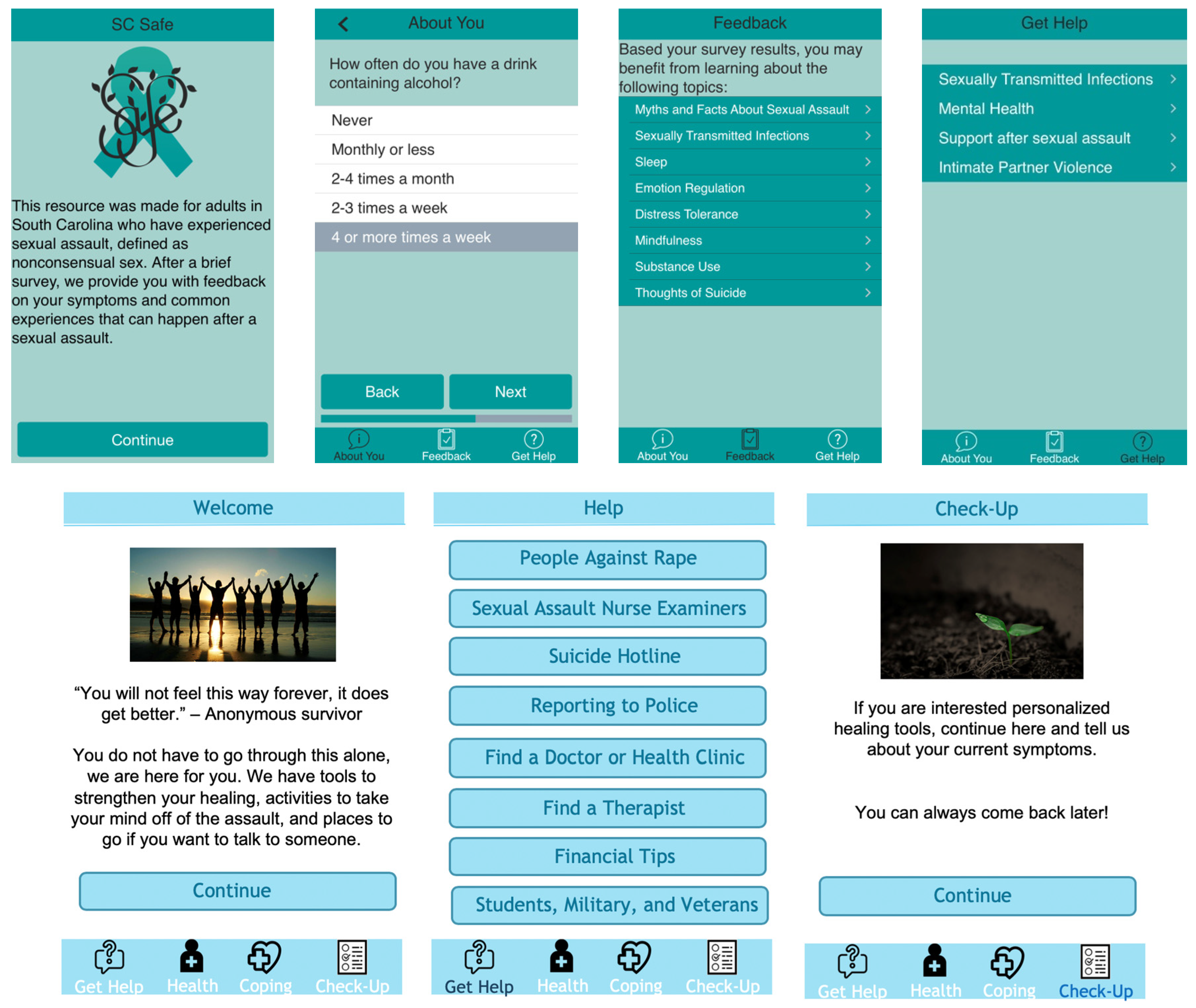

2.1. Mobile Health Structure

2.2. Usability Testing Overview

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Participants

2.5. Measures

2.6. Data Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Mental Health and Substance Use Sample Descriptives

3.2. Qualitative Results

I mean it’s a really—it’s pretty basic and that’s what I like about it that it’s not busy, it’s basic and also too it’s kind of sort of discreet as well. So, if somebody else does look your phone, they don’t know immediately.

I think neutral is good. You know, again if this is someone that has hurt you and they are close by, I mean you don’t want them to know that this is some kind of reporting or anything like that. You want it to be kind of incognito, so I think I mean I like it.

The thing honestly that kept me from going to my regular appointments afterwards was just the time because, you know, geographically I was pretty far out of there. So, to get to my appointment, have the appointment and get home, it took three, three and a half hours out of my day. And what if you’re working on job, it’s kind of difficult to—I mean you can sneak out for an hour, an hour and a half but I mean it’s kind of hard to carve out three hours in a day.

Just being aware of the resources like, the ignorance of the resources. And even if they’re aware of the resources, the ignorance of the fact that like, a lot of these are not very cost preventative. They’ll work with you because they are a victim of a crime.

I mean not wanting to talk about that, that’s a big thing. Maybe feeling like people won’t believe you that’s a pretty big things for me at least. I guess and some people don’t really want to come forward and talk to their family about it. So, I guess how your family might react, that can be a pretty big thing.

You know, just sometimes I just I don’t want to talk about it anymore. I have talked it, I’ve gone through it, I don’t want to have to keep reliving it week after week after week for the rest of my life or six months or a year however long it takes. You know, so that’s a big emotional barrier. You know, some people like myself included, you know, I’ve had an experience. I’ve done like the more intensive therapy and, you know, it’s almost a year out now for me and I have got a life that I have to get back to.

One of the things I really like seeing was the myth [dispelling the myth was presented in the content] “Men can’t be sexually assaulted” you know. What making perpetuate is that, I was – one of my base issues going to the group is, guys are really underrepresented in this area. It’s been really hard to find support systems just because I am a guy.

So, if they’re just looking to see if this really happened to them, it’s useful information or ‘does [this] happen to me’, let me see where I can get more information, you know, what do I do, what’s my next step? Very true, very true. People don’t get that enough. The perpetrator is always 100% responsible. People don’t know that enough. So, it’s just very well put together. It’s very well thought out.

With suicide already being stigmatized the way it is, and communication about suicide being stigmatized the way it is, I would want to know that like, it’s okay to talk about this and it’s okay if this is what you’re feeling like.

They still have mindset of, you can get over it, it’s not that big a deal. But it’s that deep-rooted fear through all of us rest of our lives. So, a lot of people are just going to ignore and I think that’s something that needs to be addressed and considered more than it is. And then the fears that come with the PTSD like flashbacks, nightmares, stuff like that. Yeah there is hope for that and just showing that there is something you can do about it.

People don’t always know how to constructively express their selves. And they resort to drugs and alcohol. And that isn’t the way, that always makes it worse. So, if you got something like this and you said immediately, if you fail on this do this or something similar to do this. Take a walk, call neighbor, you know. They have the information right there, just they have to—they just have to get the information, the right information, not to any drugs or alcohol. So, a lot of people, that’s what people do. That’s very important.

This one is the best one, because it’s says, “you may experience, even though you don’t do anything wrong, but you may experience of these too even though you didn’t do anything wrong and it’s okay to have these—it’s okay to have all these feelings. It just what you do with it”.

Stress is something that I feel it’s close with a lot of people especially people that don’t have experience this and people that are actually, you know, that are going through something, not only this but something really traumatic. So, that’s really something good to read and something that you can kind of read, kind of figure out how to control it and how to settle down and just kind of relax after going through something and you’re not exactly sure how to cope with.

I do appreciate that mindfulness has its own little bar because I do feel like mindfulness is something that a lot of people aren’t aware of. They aren’t aware of the benefits, they aren’t aware of how to be mindful. Mindfulness for me is one of my go-to coping mechanisms, being aware of everything in my surrounding area especially if I’m triggered by sight, sight by location specifically. If I can pay attention to something else that’s in that area, I can distract myself from the triggering event. And I like that you break down the different types of mindfulness because, yes there is mindfulness through your senses but there’s also mindfulness in an activity.

Bring identity into it [SC-Safe] as much as possible. I think just saying anything about specific identities like race/ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation, included or intersected with homelessness—or just anything like that that people might have questions about beyond the general facts that you’re giving. Because that information is really useful, because people might say ‘what about this?’ and that info would be really helpful to have—especially if there has been research done already like for the group in question you could say ‘people in this group are more likely to experience something like that’.

3.3. Descriptive Results for Service Providers

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walters, M.; Chen, J.; Breiding, M. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011.

- Peterson, C.; Degue, S.; Florence, C.; Lokey, C.N. Lifetime Economic Burden of Rape among U.S. Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, E.R.; Menon, S.V.; Bystrynski, J.; Allen, N.E. Sexual assault victimization and psychopathology: A review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenkamp, M.M.; Dickstein, B.D.; Salters-Pedneault, K.; Hofmann, S.; Litz, B.T.; Salters-Pedneault, K. Trajectories of PTSD symptoms following sexual assault: Is resilience the modal outcome? J. Trauma Stress 2012, 25, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office on Violence against Women. National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examinations; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Fitzgerald, K.; Wooler, S.; Petrovic, D.; Crickmore, J.; Fortnum, K.; Hegarty, L.; Fichera, C.; Kuipers, P. Barriers to Engagement in Acute and Post-Acute Sexual Assault Response Services: A Practice-Based Scoping Review. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Heal. Hum. Resil. 2017, 19, 1522–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T.; Evans, L.; Stevenson, E.; Jordan, C.E. Barriers to Services for Rural and Urban Survivors of Rape. J. Interpers. Violence 2005, 20, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, W.A.; Banyard, V.L.; Moynihan, M.M.; Ward, S.; Cohn, E.S. Disclosure and Service Use on a College Campus After an Unwanted Sexual Experience. J. Trauma Dissociation 2010, 11, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnell, D.; Peterson, R.; Berliner, L.; Stewart, T.; Russo, J.; Whiteside, L.; Zatzick, D. Factors Associated with Follow-Up Attendance among Rape Victims Seen in Acute Medical Care. Psychiatry 2015, 78, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.K.; Jaffe, A.E.; Hahn, C.K.; Ridings, L.E.; Gill-Hopple, K.; Lazenby, G.B.; Flanagan, J.C. Intimate Partner Violence and Completion of Post-Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examination Follow-Up Screening. J. Interpers. Violence 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, D.; Sugar, N.; Fine, D.; Eckert, L. Sexual assault victims: Factors associated with follow-up care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1653–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkner, A.; Relyea, M.; Ullman, S.E. PTSD and problem drinking in relation to seeking mental health and substance use treatment among sexual assault survivors. Traumatology 2018, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Monk-Turner, E. Circumstances surrounding male sexual assault and rape: Findings from the national violence against women survey. J. Interpers. Violence 2009, 24, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, L.H.; Alonso, J.; Mneimneh, Z.; Wells, J.E.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Borges, G.; Florescu, S. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojtabai, R.; Olfson, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Jin, R.; Druss, B.; Wang, P.S.; Kessler, R.C. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donne, M.D.; DeLuca, J.; Pleskach, P.; Bromson, C.; Mosley, M.P.; Perez, E.T.; Frye, V. Barriers to and facilitators of help-seeking behavior among men who experience sexual violence. Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchik, J.A.; McLean, C.; Rafie, S.; Hoyt, T.; Rosen, C.S.; Kimerling, R. Perceived barriers to care and provider gender preferences among veteran men who have experienced military sexual trauma: A qualitative analysis. Psychol. Serv. 2013, 10, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, S.; Duggan, M. Health online 2013. Health 2013, 2013, 1–55. Available online: http://bibliobase.sermais.pt:8008/BiblioNET/Upload/PDF5/003820.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Kilpatrick, D.G.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Acierno, R.; Saunders, B.E.; Resnick, H.S.; Best, C.L. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.E.; Cranston, C.C.; Davis, J.L.; Newman, E.; Resnick, H. Psychological outcomes after a sexual assault video intervention: A randomized trial. J. Forensic Nurs. 2015, 11, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, H.S.; Acierno, R.; Amstadter, A.B.; Self-Brown, S. An acute post-sexual assault intervention to prevent drug abuse: Updated Findings. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Hamilton, A.; Keyes, K.M. Trauma Exposure, Incident Psychiatric Disorders, and Disorder Transitions in a Longitudinal Population Representative Sample. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 92, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.K.; Flanagan, J.C. Acute mental health symptoms among individuals receiving a sexual assault medical forensic exam: The role of previous intimate partner violence victimization. Arch. Women’s Ment. Heal. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, D.L.; Patterson, D.; Resko, S. Lessons learned from iCare: A postexamination text-messaging-based program with sexual assault patients. J. Forensic Nurs. 2017, 13, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S.E.; Clifasefi, S.L.; Loganm, D.E.; Samples, L.; Somers, J.; Marlatt, G.A. Harm reduction: Current status, historical highlights and basic principles. In Harm Reduction: Pragmatic Strategies for Managing High-Risk Behaviors, 2nd ed.; Marlatt, G.A., Witkiewitz, K., Larimer, M.E., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, R.D.; Best, T.; Wilksch, S.R.; Angelakis, S.; Beatty, L.J.; Weber, N. Cognitive Processing Therapy for the Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder Following Sexual Assault: A Randomised Effectiveness Study. Behav. Chang. 2016, 33, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bedard-Gilligan, M.; Marks, E.; Graham, B.; Garcia, N.; Jerud, A.; Zoellner, L. Prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for military sexual trauma-related posttraumatic stress disorder. In Treating Military Sexual Trauma; Springer Publishing Company, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez, C.W.; Hopko, D.R.; Hopko, S.D. A brief behavioral activation treatment for depression. Treatment manual. Behav. Modif. 2001, 25, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linehan, M. DBT Skills Training Manual; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Sexual Assault and Abuse and STDs. 2015. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/sexual-assault.htm (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Tullis, T.; Albert, B. Measuring the User Experience: Collecting, Analyzing, And Presenting Usability Metrics; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ferney, S.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Eakin, E.G.; Owen, N. Randomized trial of a neighborhood environment-focused physical activity website intervention. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinchliffe, A.; Mummery, W.K. Applying usability testing techniques to improve a health promotion website. Heal. Promot. J. Aust. 2008, 19, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.; Marshall, A.; Owen, N.; Bauman, A. Engagement and retention of participants in a physical activity website. Prev. Med. 2005, 40, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J.L.; Augustson, E.M.; Mabry, P.L. The importance of usability testing in the development of an internet-based smoking cessation treatment resource. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2006, 8, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taualii, M.; Bush, N.; Bowen, D.J.; Forquera, R. Adaptation of a Smoking Cessation and Prevention Website for Urban American Indian/Alaska Native Youth. J. Cancer Educ. 2010, 25, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Given, L.M. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Koss, M.P.; Abbey, A.; Campbell, R.; Cook, S.; Norris, J.; Testa, M.; Ullman, S.; West, C.; White, J. Revising the SES: A Collaborative Process to Improve Assessment of Sexual Aggression and Victimization. Psychol. Women Q. 2007, 31, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care 2003, 41, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). 2013. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 28 July 2019).

- Bovin, M.J.; Marx, B.P.; Weathers, F.W.; Gallagher, M.W.; Rodriguez, P.; Schnurr, P.P.; Keane, T.M. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortmann, J.H.; Jordan, A.H.; Weathers, F.W.; Resick, P.A.; Dondanville, K.A.; Hall-Clark, B.; Foa, E.B.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Yarvis, J.S.; Hembree, E.A.; et al. Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, K.; Kivlahan, D.R.; McDonell, M.B.; Fihn, S.D.; Bradley, K.A. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C) an Effective Brief Screening Test for Problem Drinking. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, R.J.; Steinbauer, J.R.; Cantor, S.B.; HOLZERIII, C. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screen for at-risk drinking in primary care patients of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. Addiction 1997, 92, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, K.A.; Bush, K.R.; Epler, A.J.; Dobie, D.J.; Davis, T.M.; Sporleder, J.L.; Kivlahan, D.R. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Qualitative Research in Clinical and Health Psychology; Rohleder, P., Lyons, A., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014; pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield, M.; Chapman, A.; Chapman, C. Qualitative research in healthcare: An introduction to grounded theory using thematic analysis. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2015, 45, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.F.; Gros, K.S.; Davidson, T.M.; Barr, S.; Cohen, J.; Deblinger, E.; Ruggiero, K.J. National trainers’ perspectives on challenges to implementation of an empirically-supported mental health treatment. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2014, 41, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, T.M.; Lopez, C.M.; Saulson, R.; Borkman, A.L.; Soltis, K.; Ruggiero, K.J.; De Arellano, M.; Wingood, G.M.; DiClemente, R.J.; Danielson, C.K. Development and preliminary evaluation of a behavioural HIV-prevention programme for teenage girls of Latino descent in the USA. Cult. Heal. Sex. 2014, 16, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davidson, T.M.; Soltis, K.; Albia, C.M.; de Arellano, M.; Ruggiero, K.J. Providers’ perspectives regarding the development of a web-based depression intervention for Latina/o youth. Psychol. Serv. 2015, 12, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelligrini, A.D. Observing Children in Their Natural Worlds: A Methodological Primer, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg, A.L.; Parks, K.A.; Collins, R.L.; Hughes, T.L. Sexual assault risks among gay and bisexual men. J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.C.; Basile, K.C.; Breiding, M.J.; Smith, S.G.; Walters, M.L.; Merrick, M.T.; Chen, J.; Stevens, M.R. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011.

- Alegría, M.; Vallas, M.; Pumariega, A.J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pediatric Mental Health. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2010, 19, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cochran, S.D. Emerging issues in research on lesbians’ and gay men’s mental health: Does sexual orientation really matter? Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 931–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, K.H.; Bradford, J.B.; Makadon, H.J.; Stall, R.; Goldhammer, H.; Landers, S. Sexual and Gender Minority Health: What We Know and What Needs to Be Done. Am. J. Public Heal. 2008, 98, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | ||

| Race | ||

| White | 13 | 100 |

| Ethnicity 1 | ||

| Non-Hispanic/Latina | 10 | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 2 | 15.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 11 | 84.6 |

| Male | 1 | 7.7 |

| Other 2 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 7 | 53.8 |

| Dating | 4 | 30.8 |

| Serious Relationship | 2 | 15.4 |

| Married | 1 | 7.7 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 |

| Student Status | ||

| Not current a student | 10 | 76.9 |

| Currently a student | 3 | 23.1 |

| Active Duty Member | ||

| No | 12 | 92.3 |

| Yes | 1 | 7.7 |

| Insurance Status | ||

| Insurance | 10 | 76.9 |

| No Insurance | 3 | 23.1 |

| Time Since Sexual Assault Occurred 1 | ||

| 2–4 weeks | 1 | 7.7 |

| 1–6 months | 2 | 15.4 |

| 6–12 months | 2 | 15.4 |

| 12–24 months | 6 | 42.2 |

| Assaults that Involved Incapacitation | 8 | 61.5 |

| Relationship with Perpetrator | ||

| Stranger | 5 | 38.5 |

| Acquaintance | 7 | 53.8 |

| Partner | 1 | 7.7 |

| Core Theme | Sub Theme |

|---|---|

| Aesthetics and Usability | • App is simple and not overwhelming |

| • Layout allows for privacy | |

| • Increase color brightness and font size | |

| • Make navigation functions clear and uniform across app | |

| Barriers to Resources | • Logistical barriers (e.g., distance, cost, awareness of resources) |

| • Attitudinal barriers (e.g., denial, perceived stigma) | |

| Opinions about SC-Safe | • Education module was informative and helpful |

| • Feedback on emotional and behavioral health module | |

| • Feedback on general coping skills |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gilmore, A.K.; Davidson, T.M.; Leone, R.M.; Wray, L.B.; Oesterle, D.W.; Hahn, C.K.; Flanagan, J.C.; Gill-Hopple, K.; Acierno, R. Usability Testing of a Mobile Health Intervention to Address Acute Care Needs after Sexual Assault. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173088

Gilmore AK, Davidson TM, Leone RM, Wray LB, Oesterle DW, Hahn CK, Flanagan JC, Gill-Hopple K, Acierno R. Usability Testing of a Mobile Health Intervention to Address Acute Care Needs after Sexual Assault. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(17):3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173088

Chicago/Turabian StyleGilmore, Amanda K., Tatiana M. Davidson, Ruschelle M. Leone, Lauren B. Wray, Daniel W. Oesterle, Christine K. Hahn, Julianne C. Flanagan, Kathleen Gill-Hopple, and Ron Acierno. 2019. "Usability Testing of a Mobile Health Intervention to Address Acute Care Needs after Sexual Assault" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 17: 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173088

APA StyleGilmore, A. K., Davidson, T. M., Leone, R. M., Wray, L. B., Oesterle, D. W., Hahn, C. K., Flanagan, J. C., Gill-Hopple, K., & Acierno, R. (2019). Usability Testing of a Mobile Health Intervention to Address Acute Care Needs after Sexual Assault. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(17), 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173088