Critical Success Factors of Medical Tourism: The Case of South Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Definition of Medical Tourism

3. Medical Tourism Success Factors

3.1. Increased Demand

3.2. Suppliers’ Rigorous Investment in the Industry

3.3. The Role of the Medical Tourism Agency

4. Medical Tourism in South Korea

5. Methodology

5.1. Case Study

5.2. Samples of this Study

5.3. Data Collection and Analysis

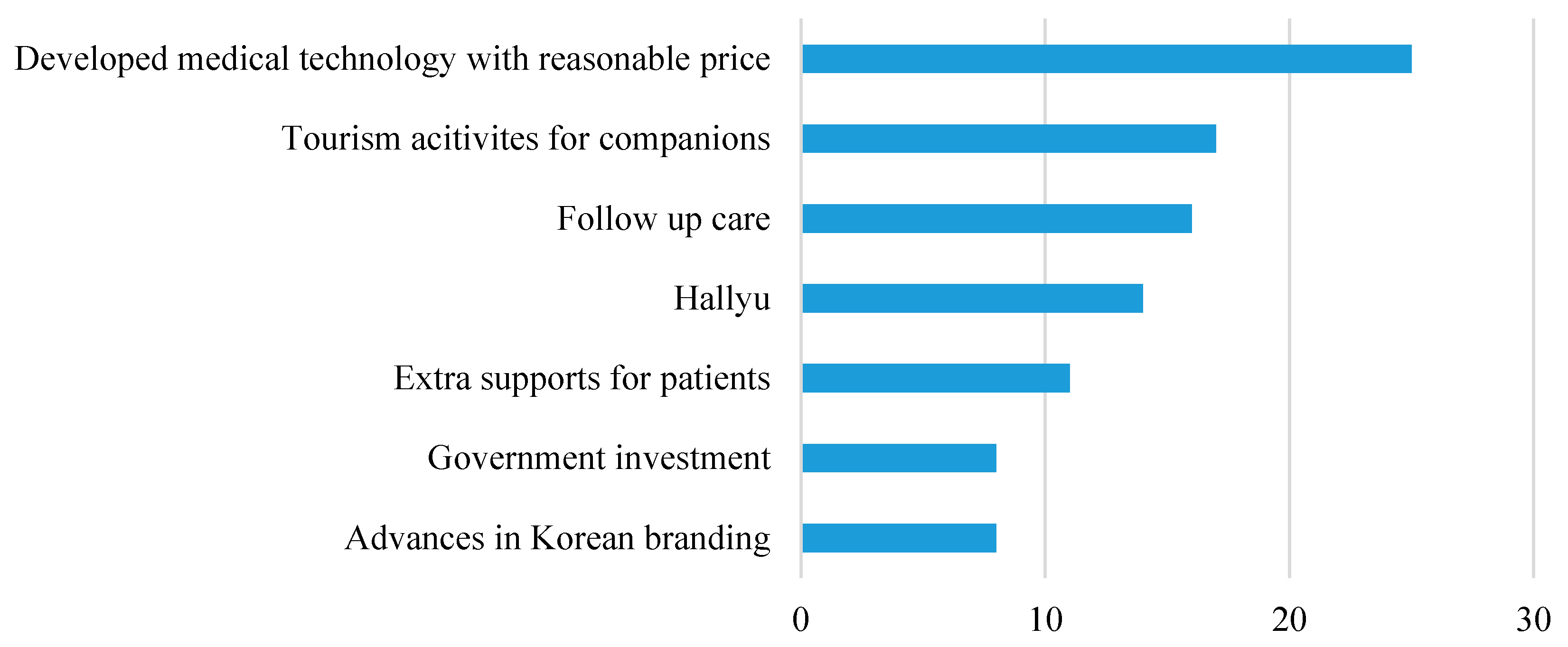

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Developed Medical Technology with a Reasonable Price

6.2. Tourism Activities for Companions

6.3. Follow up Care

6.4. The Effect of Hallyu

6.5. Extra Support for Patients

6.6. Government Investment

6.7. Advances in Korea Branding

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, H.; Hwang, J. Growing competition in the healthcare tourism market and customer retention in medical clinics: New and experienced travellers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 680–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetscherin, M.; Stephano, R.M. The medical tourism index: Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.; Kucukusta, D.; Song, H. A conceptual model of medical tourism: Implications for future research. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, M.; Sulianti, D. More than medical tourism: Lessons from Indonesia and Malaysia on South–South intra-regional medical travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Hoz-Correa, A.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Bakucz, M. Past themes and future trends in medical tourism research: A co-word analysis. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, V.A.; Kingsbury, P.; Snyder, J.; Johnston, R. What is known about the patient’s experience of medical tourism? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnston, R.; Crooks, V.A.; Snyder, J. “I didn’t even know what I was looking for”: A qualitative study of the decision-making processes of Canadian medical tourists. Glob. Health 2012, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taleghani, M.; Chirani, E.; Shaabani, A. Health tourism, tourist satisfaction and motivation. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2011, 3, 546–555. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, D.S. Medical tourism: An emerging global healthcare industry. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2017, 10, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, S.; Ebrahim, A.H. A qualitative analysis of Singapore’s medical tourism competitiveness. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.; Johnston, R.; Crooks, V.A.; Morgan, J.; Adams, K. How medical tourism enables preferential access to care: Four patterns from the Canadian context. Health Care Anal. 2017, 25, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand View Research. Medical Tourism Market. Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report 2018–2025: Focus on Costa Rica, Mexico, India, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buzinde, C.N.; Yarnal, C. Therapeutic landscapes and postcolonial theory: A theoretical approach to medical tourism. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, J. Contemporary medical tourism: Conceptualisation, culture and commodification. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Ko, T.G. A cross-cultural study of perceptions of medical tourism among Chinese, Japanese and Korea tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, A.N.; Choong, Y.O.; Moorthy, K.; Chan, L.M. Intention to visit Malaysia for medical tourism using the antecedents of Theory of Planned Behaviour: A predictive model. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. Medical tourism: Sea, sun, sand and … surgery. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Ritter, T.; Gemunden, H.G. Value creation in buyer-seller relationships: Theoretical considerations and empirical results from a supplier’s perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallem, Y.; Barth, I. Customer-perceived value of medical tourism: An exploratory study—The case of cosmetic surgery in Tunisia. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Po Lo, H.; Chi, R.; Yang, Y. An integrated framework for customer value and customer-relationship-management performance: A customer-based perspective from China. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2004, 14, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomerdijk, L.G.; Voss, C.A. Service design for experience-centric services. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, G.; Baylis, F. The ethical physician encounters international medical travel. J. Med. Ethics 2010, 36, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helble, M. The movement of patients across borders: Challenges and opportunities for public health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.-C.; du Cros, H.; Vong, T.N. Macao’s potential for developing regional Chinese medical tourism. Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, L. ‘First world health care at third world prices’: Globalization, bioethics and medical tourism. BioSocieties 2007, 2, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Gill, H. Exploring the factors that affect the choice of destination for medical tourism. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2011, 4, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, C.M. Health and medical tourism: A kill or cure for global public health? Tour. Overv. 2011, 66, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, M.J.; Labonté, R.; Lu, Z. Patients beyond borders: A study of medical tourists in four countries. Glob. Soc. Policy 2010, 10, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Altes, A. The development of health tourism services. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.G.; York, V.K.; Brannon, L.A. Travel for treatment: Students’ perspective on medical tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.S. Constructions and experiences of authenticity in medical tourism: The performances of places, spaces, practices, objects and bodies. Tour. Stud. 2010, 10, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesar, O.; Rimac, K. Medical tourism development in Croatia. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2011, 14, 107–134. [Google Scholar]

- Lunt, N.; Carrera, P. Medical tourism: Assessing the evidence on treatment abroad. Maturitas 2010, 66, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrera, P.M.; Bridges, J.F. Globalization and healthcare: Understanding health and medical tourism. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2006, 6, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, R.; Crooks, V.A.; Adams, K.; Snyder, J.; Kingsbury, P. An industry perspective on Canadian patients’ involvement in medical tourism: Implications for public health. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Connell, J. A new inequality? Privatisation, urban bias, migration and medical tourism. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2011, 52, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, C.R.; Sauer, K.M. A survey of medical tourism service providers. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2011, 5, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, L.G. Quality in health care and globalization of health services: Accreditation and regulatory oversight of medical tourism companies. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2010, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ye, B.H.; Qiu, H.Z.; Yuen, P.P. Motivations and experiences of Mainland Chinese medical tourists in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afthanorhan, A.; Awang, Z.; Salleh, F.; Ghazali, P.; Rashid, N. The effect of product quality, medical price and staff skills on patient loyalty via cultural impact in medical tourism. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1421–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewole, P. Prospects for developing country exports of services to the year 2010: Projections and public policy implications. J. Macromark. 2001, 21, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadzi, W.; Panda, D. Medical Tourism: Globalization and the marketing of medical services. Consort. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 11, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, L.L.; Frederick, J.R. Medical tourism facilitators: Patterns of service differentiation. J. Vacat. Mark. 2011, 17, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, T.C.; Liu, J.S.; Lu, L.Y.; Lee, Y. he main paths of medical tourism: From transplantation to beautification. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, B.S.; Henson, J.L.N.; Dotson, M.J. Characteristics of consumers likely and unlikely to participate in medical tourism. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2015, 8, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. Relationships among senior tourists’ perceptions of tour guides’ professional competencies, rapport, satisfaction with the guide service, tour satisfaction, and word of mouth. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. Antecedents and consequences of brand prestige of package tour in the senior tourism industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Understanding first-class passengers’ luxury value perceptions in the US airline industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, H.L. Medical tourism and the state in Malaysia and Singapore. Glob. Soc. Policy 2010, 10, 336–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lee, T.J.; Noh, H. Characteristics of a medical tourism industry: The case of South Korea. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 856–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, J. Patients Beyond Borders: Everybody’s Guide to Affordable, World-Class Medical Tourism; Healthy Travel Media: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cormany, D.; Baloglu, S. Medical travel facilitator websites: An exploratory study of web page contents and services offered to the prospective medical tourist. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bookman, M.Z.; Bookman, K.R. Medical Tourism in Developing Countries; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Mutalib, N.S.; Soh, Y.C.; Wong, T.W.; Yee, S.M.; Yang, Q.; Murugiah, M.K.; Ming, L.C. Online narratives about medical tourism in Malaysia and Thailand: A qualitative content analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, L.; Labonté, R.; Runnels, V.; Packer, C. Medical tourism today: What is the state of existing knowledge? J. Public Health Policy 2010, 31, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Han, H.; Lockyer, T. Medical tourism—Attracting Japanese tourists for medical tourism experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junio, M.M.V.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, T.J. Competitiveness attributes of a medical tourism destination: The case of South Korea with importance-performance analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J. Traditional Korean medicine a gamechanger in medical tourism industry. The Korean Herald. 1 November 2018. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20181101000771 (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Korea Health Industry Development Institute. Statistics on International Patients in Korea; Korea Health Industry Development Institute: Cheongju-si, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jang, S.G. Samsung becomes first Korean brand to enter ‘Global Top 10’; Yonhap News: Seoul, Korea, 2 October 2012; p. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vision/Goals. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/eng/index.jsp (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Policies. Available online: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_policy/dept/deptList.jsp?pType=05 (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Tang, C.F.; Lau, E. Modelling the demand for inbound medical tourism: The case of Malaysia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Beeton, S. The case study in tourism research: A multi-method case study approach. In Tourism Research Methods: Integrating Theory Practice; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings about Case Study Research, Corrected. In Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2012; pp. 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, T.; Yu, J.; Han, H. Medical tourism in Korea–Recent phenomena, emerging markets, potential threats, and challenge factors: A review. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavana, R.Y.; Delahaye, B.L.; Sekaran, U. Applied Business Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Milton, QLD, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Veal, A.J. Research Methods for Leisure and Tourism: A Practical Guide; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, O.R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, P.J.; Reese, S.D. Mediating the Message: Theories of Influences on Mass Media Content; Longman: White Plains, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Kirilenko, A.P.; Morrison, A.M. Facilitating content analysis in tourism research. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainil, T.; Platenkamp, V.; Meulemans, H. The discourse of medical tourism in the media. Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y. Value as a medical tourism driver. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2012, 22, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Han, G.-S. Korean cosmetic surgery and digital publicity: Beauty by Korean design. Media Int. Aust. 2011, 141, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickert, K. A brief history of Medical Tourism. Available online: http://content.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1861919,00.html (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Han, H.J.; Lee, J.S. A study on the KBS TV drama Winter Sonata and its impact on Korea’s Hallyu tourism development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Agrusa, J.; Lee, H.; Chon, K. Effects of Korean television dramas on the flow of Japanese tourists. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Long, P.; Robinson, M. Small screen, big tourism: The role of popular Korean television dramas in South Korean tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2009, 11, 308–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, S.; Giouvris, E. Tourist arrivals in Korea: Hallyu as a pull factor. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, H.; Chon, K.-S. Segmentation of different types of Hallyu tourists using a multinomial model and its marketing implications. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.H. Local buzz, global pipelines and Hallyu: The case of the film and TV industry in South Korea. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 4, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, P. My, What Big Eyes You Have: Young Chinese Drive Korea’s Plastic Surgery Boom. Available online: https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2011/0301/My-what-big-eyes-you-have-Young-Chinese-drive-Korea-s-plastic-surgery-boom (accessed on 28 September 2018).

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Customer retention in the medical tourism industry: Impact of quality, satisfaction, trust, and price reasonableness. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, C.; Ham, S. Medical hotels in the growing healthcare business industry: Impact of international travelers’ perceived outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1869–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J. Investigating healthcare hotel travelers’ overall image formation: Impact of cognition, affect, and conation. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skountridaki, L. Barriers to business relations between medical tourism facilitators and medical professionals. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interbrand. The Top 100 Brands. Available online: https://www.interbrand.com/best-brands/best-global-brands/2019/ranking/ (accessed on 13 November 2019).

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. Are other customer perceptions important at casino table games? Their impact on emotional responses and word-of-mouth by gender. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Cho, S.-B.; Kim, W. Consequences of psychological benefits of using eco-friendly services in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. South Korea’s Plastic Surgery Boom: A Quest To Be ‘Above Normal’. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/korea-plastic-surgery_l_5d72afb0e4b07521022c00e1 (accessed on 13 September 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Arcodia, C.; Kim, I. Critical Success Factors of Medical Tourism: The Case of South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4964. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244964

Kim S, Arcodia C, Kim I. Critical Success Factors of Medical Tourism: The Case of South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(24):4964. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244964

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Soojung, Charles Arcodia, and Insin Kim. 2019. "Critical Success Factors of Medical Tourism: The Case of South Korea" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 24: 4964. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244964

APA StyleKim, S., Arcodia, C., & Kim, I. (2019). Critical Success Factors of Medical Tourism: The Case of South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 4964. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16244964