Employment Experiences among Young Malaysian Adults with Learning Disabilities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Variables of the Study

3. Results

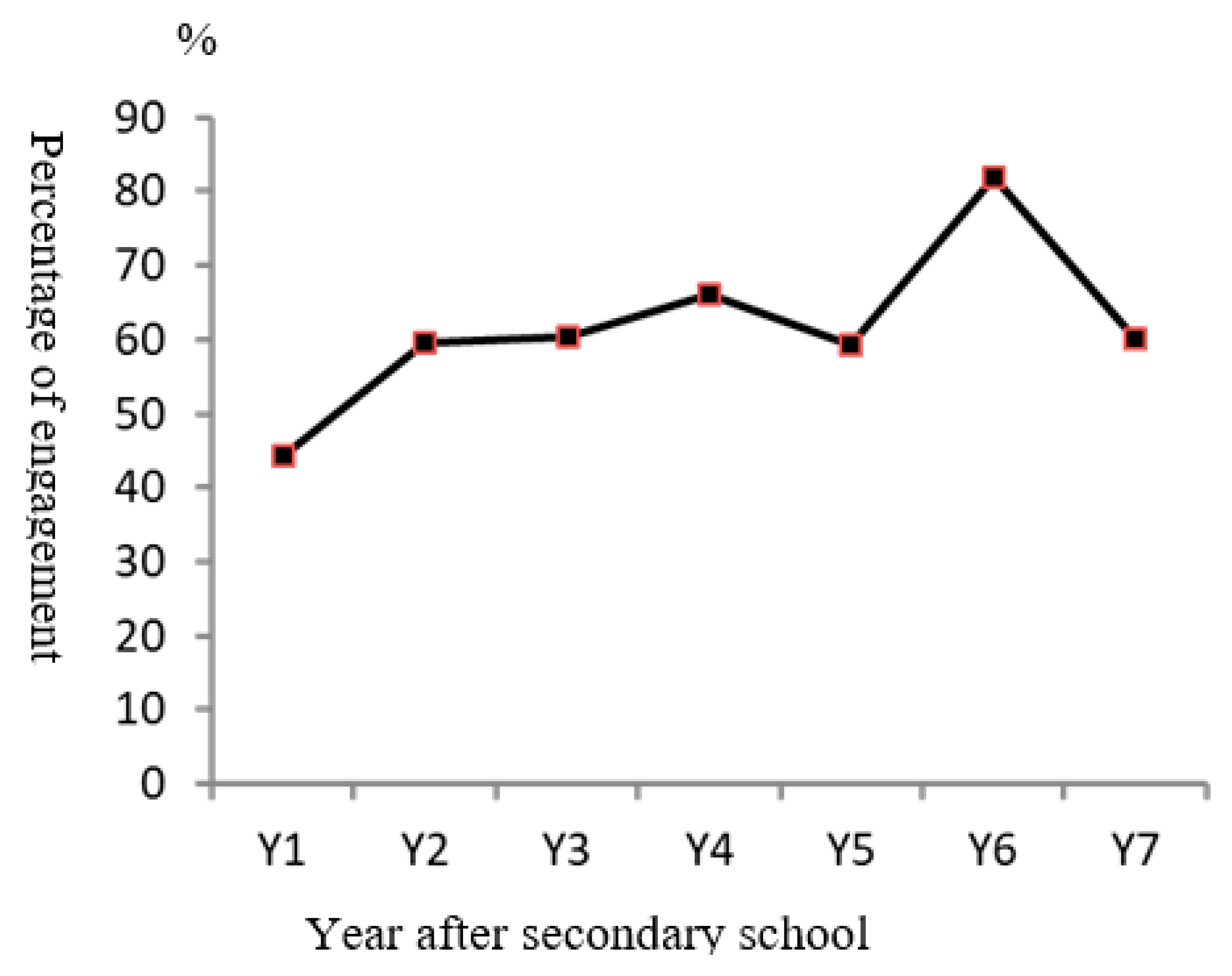

3.1. Respondents’ Characteristics and Employment Experience

3.2. Factors Associated with Employment

3.3. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blackorby, J.; Wagner, M. Longitudinal post-school outcomes of youth with disabilities: Findings from the national longitudinal transition study. Except. Child. 1996, 62, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J. Navigating the beyond-school years: Employment and success for adults with learning disabilities. Career Plan. Adult Dev. J. 2002, 18, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Khor, H.T. The Employment of Persons with Disabilities in Malaysia. Soc.-Econ. Environ. Res. Inst. 2002, 4, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, K.; Bates, P.; Hunter, D. Transition to Adult Life for Persons with Disabilities, 2nd ed.; Training Resource Network Inc.: St. Augustine, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cameto, R. Employment of youth with disabilities after high school. In After High School: A First Look at the Postschool Experiences of Youth with Disabilities. A Report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2(NLTS2); Wagner, M., Newman, L., Cameto, R., Garza, N., Levine, P., Eds.; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2005; Available online: http://www.nlts2.org (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Benz, M.R.; Yovanoff, P.; Doren, B. School-to-work components that predict post-school success for students with and without disabilities. Except. Child. 1997, 63, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaus, W.J. Employment Outcomes of University Graduates with Learning Disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2006, 29, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. Life outside of school. In Life Outside the Classroom for Youth with Disabilities. A Report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2); Wagner, M., Cadwallader, T.W., Marder, C., Cameto, R., Cardoso, D., Garza, N., Levine, P., Newman, L., Eds.; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2003; Available online: http://www.nlts2.org/pdfs/life_outside_school_ch7.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Hogansen, M.J.; Powers, K.; Geenen, S.; Gil-Kashiwabara, E.; Powers, L. Transition goals and experience of females with disabilities: Youth, parents, and Professional. Except. Child. 2008, 74, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldberg, J.R.; Higgins, L.E.; Raskind, H.M.; Herman, L.K. Predictors of success in individuals with learning disabilities: A qualitative analysis of a 20-year longitudinal study. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2003, 18, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaus, W.J.; Zhao, J.; Ruban, L. Employment Satisfaction of University Graduates with Learning Disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2008, 29, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiston, C.S.; Kellet, B.K. The influences of the family of origin on career development: A review and analysis. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 32, 493–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morningstar, M.E.; Turnbull, P.A.; Turnbull, R.H. What do students with disabilities tell us about the importance of family involvement in the transition from school to adult life? Except. Child. 1995, 62, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rojewski, J.W.; Kim, H. Career choice patterns and behavior of work-bound youth during early adolescence. J. Career Dev. 2003, 30, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, L.; Doren, B.; Metheny, J.; Johnson, P.; Zane, C. Transition to Employment: Role of the Family in Career Development. Except. Child. 2007, 73, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzo, J.; Tighe, E.; Childs, S. Family Involvement Questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Chaves, A.P.; Diemer, M.A.; Gallagher, L.A.; Marshall, K.G.; Sirin, S.; Bhati, K.S. Voices of the forgotten half: The role of social class in the school-to-work transition. J. Couns. Psychol. 2002, 49, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliza, A. Internship in the Transition Program from School to Work. GJAT 2019, Special Issue, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rojewski, J.W. Occupational and educational aspirations and attainment of young adults with and without LD 2 years after high school completion. J. Learn. Disabil. 1999, 32, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C. A Status Report on Transition Planning for Individuals with Learning Disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 1996, 29, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, P.D. A Taxonomy for Transition Programming: Linking Research and Practice; University of Illinois, Transition Research Institute: Champaign, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, S.A.; Yovanoff, P.; Doren, B.; Benz, R.M. Predicting participation in postsecondary education for school leavers with disabilities. Except. Child. 1995, 62, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigal, M.; Test, W.D.; Beattie, J.; Wood, M.W. An evaluation of transition components of individualized education programs. Except. Child. 1997, 63, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, P.D.; Field, S. Transition focused education: Foundation for the future. J. Spec. Educ. 2003, 37, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Test, W.D.; Aspel, P.N.; Everson, M.J. Transition Methods for Youth with Disabilities; Pearson Printice Hall: Upper Saddle, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, W.N. Learning Disabilities: Characteristics, Identification, and Teaching Strategies, 5th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, M.R.; Lindstrom, L.; Yovanoff, P. Improving graduation and employment outcomes of students with disabilities: Predictive factors and student perspectives. Except. Child. 2000, 66, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojewski, J.W. Key components of model transition services for students with learning disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 1992, 15, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. Learning Disabilities: Theories, Diagnosis and Teaching Strategies, 9th ed.; Northeastern Illinois University: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, C.; Sitlington, P.; Alper, S. Postsecondary education for students with learning disabilities: A synthesis of the literature. Except. Child. 2001, 68, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, P.B.; Vogel, S.A. Issues in the employment of adults with learning disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 1993, 16, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.A.; Gerber, P.J. At Second Glance: Employers and Employees with Learning Disabilities in the Americans with Disabilities Act Era. J. Learn. Disabil. 2001, 34, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusch, F.R.; Hughes, C.; Agran, M.; Martin, J.E.; Johnson, J.R. Toward self-directed learning, post-high school placement, and coordinated support constructing new transition bridges to adult life. Career Dev. Except. Individ. 2009, 32, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Blackorby, J.; Cameto, R.; Newman, L. What Makes a Difference? Influences on Post-School Outcomes of Youth with Disabilities; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, S.C.; Syed Yahya, S.Z. Effective Transitional Plan from Secondary Education to Employment for Individuals with Learning Disabilities: A Case Study. J. Educ. Learn. 2013, 2, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Social Welfare Department. Sheltered Workshop. 2016. Available online: http://www.jkm.gov.my/jkm (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Aliza, A. Transition Program: The Challenges Faced by Special Needs Students in Gaining Work Experience. Int. Educ. Stud. 2014, 7, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N.; Yasin, M.H.; Abdullah, N.A. Implementation of the inter-agency collaboration in vocational education of students with learning disabilities towards preparation of career experience. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, N.M.; Yasin, M.H. The Application of Epstein’s Model in the Implementation of Career Transition Programme for Students with Learning Disabilities. J. Penelit. Pengemb. Pendidik. Luar Biasa 2018, 5, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- PWD Act. Law of Malaysia; Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Welfare. Pekeliling Perkhidmatan Bilangan 3; Government Service Circular No. 3; Malaysia Public Service Department: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2008.

- Anizam, M.Y.; Manisah, M.A.; Amla, M.S. Youth workers with disabilities: The views of employers in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 204, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, E.S.; Clark, R. How It’s Done: An Invitation to Social Research; Thomson Higher Education: Belmont, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; The Psychological Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M.; Newman, L.; Cameto, R.; Garza, N.; Levine, P. Summary Report. In After High School: A First Look at the Post-School Experiences of Youth with Disabilities. A Report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2(NLTS2); SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2005; Available online: http://www.nlts2.org (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Newman, L.; Wagner, M.; Cameto, R.; Knokey, A.M. The Post-High School Outcomes of Youth with Disabilities up to 4 Years After High School. A Report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2); NCSER 2009–3017; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.nlts2.org (accessed on 3 November 2018).

- Dunham, M.; Koller, J.A. Comparison of adult learning disability subtypes in the vocational rehabilitation system journal of rehabilitation. Rehabil. Psychol. 1999, 44, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaus, W.J.; Ruban, L.M.; Foley, T.E.; McGuire, J.M. Factors contributing to the employment satisfaction of university graduates with learning disabilities. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2003, 26, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerber, P.J.; Price, L.A.; Mulligan, R.; Shessel, I. Beyond transition: Experiences of American and Canadian adults with LD. J. Learn. Disabil. 2004, 37, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embong, A.R. Urbanisation and urban life in Peninsular Malaysia. Akademika 2011, 81, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Furuoka, F.; Pazim, K.H.; Lim, B.; Mahmud, R. Employment situation of person with disabilities: Case studies of US, Japan and Malaysia. J. Arts Sci. Commer. 2011, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Aina, R. Comparisons of Affirmative Action in Employment for People with Disabilities in Malaysia and the United States. Master’s Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, P.; Wagner, M. The Household Circumstances and Emerging Independence of Out-of-School Youth with Disabilities. In After High School: A First Look at the Post-School Experiences of Youth with Disabilities. A Report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2(NLTS2); Wagner, M., Newman, L., Cameto, R., Garza, N., Levine, P., Eds.; SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.S.; Abdullah, S.H. Malaysian disabled women experiences in employment. Int. J. Stud. Child. Women Elder. Disabl. 2017, 1, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, Y. Occupational Therapy for People Experiencing Illness, Injury or Impairment, 7th ed.; Curtin, M., Egan, M., Adams, J., Townsend, E., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 55 | 71.4 |

| Female | 22 | 28.6 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 21 or younger | 51 | 66.2 |

| more than 21–25 | 26 | 33.8 |

| Min–Max | 18–25 | |

| Median, IQR | 23.0 (22.0–24.0) | |

| WASI 1Q score | ||

| 70–84 | 34 | 44.2 |

| 85–90 | 22 | 28.6 |

| 91 and above | 21 | 27.3 |

| Min–Max | 70–104 | |

| Median, IQR | 85 (74.0–92.0) | |

| Educational level | ||

| Certificate of ending school | 16 | 20.8 |

| PMR | 42 | 54.5 |

| SKM/SPM | 19 | 24.7 |

| Year of leaving school(years) | ||

| 3 or less | 30 | 39.0 |

| 4–7 | 47 | 61.0 |

| Min–Max | 2–7 | |

| Median, IQR | 4 (2.0–5.0) | |

| Presence of co-morbidity | ||

| Yes | 14 | 18.2 |

| No | 63 | 81.8 |

| Current living arrangement | ||

| Alone in rented house/apartment/room | 3 | 3.9 |

| With spouse or roommate in a home/apartment | 9 | 11.7 |

| With parent/guardian | 60 | 77.9 |

| With other family members | 4 | 5.2 |

| College or work hostel/accommodation | 1 | 1.3 |

| Characteristics | F | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ever employed since leaving school | (n = 77) | |

| Yes | 57 | 74.0 |

| No | 20 | 26.0 |

| Current employment status | ||

| Employed | 50 | 64.9 |

| Unemployed | 27 | 35.1 |

| No. currently employed | (n = 50) | |

| F | % | |

| Way of getting current job | ||

| Self | 12 | 24.0 |

| School/teacher | 2 | 4.0 |

| Rehabilitation Agency | 7 | 14.0 |

| Family, family/friend network | 29 | 58.0 |

| Type of current job | ||

| Competitive | 46 | 92.0 |

| Supported/from home | 1 | 2.0 |

| Other (family business) | 3 | 6.0 |

| Nature of current job | ||

| Full time | 45 | 90.0 |

| Part time | 5 | 10.0 |

| Working shift | ||

| Yes | 21 | 42.0 |

| No | 29 | 58.0 |

| Duration of current job (month) | ||

| 3 and less | 10 | 20.0 |

| More than 3–11 | 13 | 26.0 |

| 12 and longer | 27 | 54.0 |

| Working hours per day (hours) | ||

| 8 and less | 34 | 68.0 |

| More than 8-9 | 12 | 24.0 |

| 10 and more | 4 | 8.0 |

| Min–Max | 4–14/8 (8.0–9.0) | |

| Median, IQR | ||

| Working days per week(days) | ||

| 5 | 11 | 22.0 |

| 6 | 37 | 74.0 |

| 7 | 2 | 4.0 |

| Min–max/Median, IQR | 5–7/6 (6–6) | |

| Salary per-month (RM) | ||

| 500 or less | 4 | 8.0 |

| More than 500–1000 | 33 | 66.0 |

| More than 1000 -1500 | 8 | 16.0 |

| 1501 and more | 5 | 10.0 |

| Min–Max | RM150.00–1800.00 | |

| Median, IQR | RM875.00 (700.00–1050.00) | |

| Work benefits received * | ||

| SOCSO/health insurance | 41 | 82.0 |

| EPF/pension | 41 | 82.0 |

| Annual leave | 35 | 70.0 |

| Medical leave | 38 | 76.0 |

| Allowance | 20 | 40.0 |

| Bonus | 27 | 54.0 |

| Others (food, accommodation) | 7 | 14.0 |

| Characteristics | Employment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Employed N (%) | Chi square | p Values | |

| I. INDIVIDUAL | ||||

| Gender: | ||||

| Male | 55 | 40 (72.7) | x2 = 5.1333 | * p = 0.02 |

| Female | 22 | 10 (45.5) | ||

| II. FAMILY | ||||

| Family monthly income: | ||||

| Low (≤RM2300) | 32 | 25 (78.1) | x2 = 4.184 | * p = 0.04 |

| Middle to high (>RM2300) | 45 | 25 (55.6) | ||

| Mother educational level: | ||||

| Low (Primary and lower) | 15 | 14 (93.3) | x2 = 6.598 | *p = 0.01 |

| High (Secondary and higher) | 62 | 36 (58.1) | ||

| Vocational training and employment related services ** | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 9 (100.0) | x2 = 5.503 | *,a p = 0.02 |

| No | 68 | 41 (60.3) | ||

| Parent expectation | ||||

| Low | 7 | 2 (28.6) | x2 = 4.472 | *,a p = 0.048 |

| Moderate to High | 70 | 48 (68.6) | ||

| Financial support *** | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 29 (90.6) | x2 = 15.953 | * p < 0.001 |

| No | 45 | 21 (46.7) | ||

| Overall usage of support services: | ||||

| Low (≤5 types of service) | 48 | 27 (56.3) | x2 = 4.222 | * p = 0.04 |

| High (>5 types of service) | 29 | 23 (79.3) | ||

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Individual | |||

| Male vs. Female | 4.90 | 1.12 | 99.13 |

| Community | |||

| Financial support | |||

| Received vs. Not received | 10.83 | 1.70 | 69.16 |

| Constant = 0.028 | |||

| Cox & Snell R2 = 0.351 | |||

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.483 | |||

| Model x2(df)/p-value = 33.26(9)/p < 0.01 | |||

| H & L test p-value = 0.14 | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harun, D.; Che’ Din, N.; Mohd Rasdi, H.F.; Shamsuddin, K. Employment Experiences among Young Malaysian Adults with Learning Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010115

Harun D, Che’ Din N, Mohd Rasdi HF, Shamsuddin K. Employment Experiences among Young Malaysian Adults with Learning Disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarun, Dzalani, Normah Che’ Din, Hanif Farhan Mohd Rasdi, and Khadijah Shamsuddin. 2020. "Employment Experiences among Young Malaysian Adults with Learning Disabilities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010115

APA StyleHarun, D., Che’ Din, N., Mohd Rasdi, H. F., & Shamsuddin, K. (2020). Employment Experiences among Young Malaysian Adults with Learning Disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010115