Community Determinants of Physical Growth and Cognitive Development among Indian Children in Early Childhood: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.3. Individual-and Household-Level Characteristics

2.4. Community-Level Characteristics

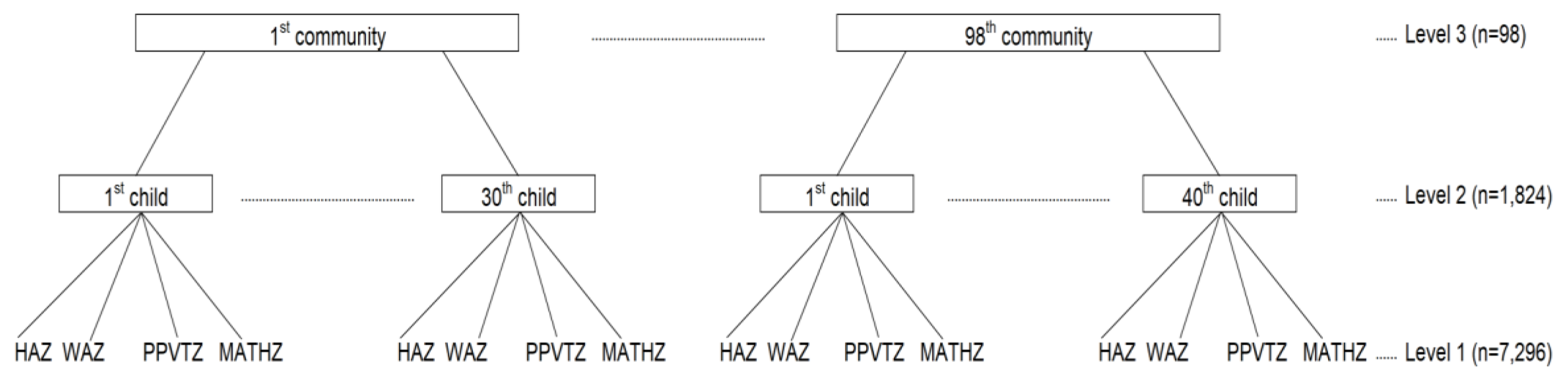

2.5. Statistical Models

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HAZ | height-for-age z-score |

| MATHZ | mathematics test scores |

| PPVT | Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test |

| PPVTZ | z-scores of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test scores |

| WAZ | weight-for-age z-score |

References

- Phillips, D.A.; Shonkoff, J.P. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grantham-McGregor, S.; Cheung, Y.B.; Cueto, S.; Glewwe, P.; Richter, L.; Strupp, B.; International Child Development Steering Group. Developmental Potential in the First 5 Years for Children in Developing Countries. Lancet 2007, 369, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dornan, P.; Woodhead, M. How Inequalities Develop through Childhood; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, J.M.; Kim, R.; Krishna, A.; McGovern, M.; Aguayo, V.M.; Subramanian, S.V. Understanding the association between stunting and child development in low- and middle-income countries: Next steps for research and intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 193 (Suppl. C), 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fogel, R.W. Health, Nutrition, and Economic Growth. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2004, 52, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Like father, like son; like mother, like daughter: Parental resources and child height. J. Hum. Resour. 1994, 29, 950–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.P.; Wachs, T.D.; Gardner, J.M.; Lozoff, B.; Wasserman, G.A.; Pollitt, E.; Carter, J.A.; International Child Development Steering Group. Child Development: Risk Factors for Adverse Outcomes in Developing Countries. Lancet 2007, 369, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, J. Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: Socioeconomic Status, Poor Health in Childhood, and Human Capital Development; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Case, A.; Lubotsky, D.; Paxson, C. Economic Status and Health in Childhood: The Origins of the Gradient; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, L. Inequality in the Early Cognitive Development of British Children in the 1970 Cohort. Economica 2003, 70, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, F.L. Socio-Economic Status and Early Childhood Cognitive Skills: Is Latin America Different? Young Lives: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hawe, P. Capturing the Meaning of ‘Community’in Community Intervention Evaluation: Some Contributions from Community Psychology. Health Promot. Int. 1994, 9, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.W.; Richard, L.; Potvin, L. Ecological Foundations of Health Promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulton, C.J.; Korbin, J.E.; Su, M.; Chow, J. Community Level Factors and Child Maltreatment Rates. Child Dev. 1995, 66, 1262–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobal, J.; Saavedra, J.; Suárez, P.; Huttly, S.; Penny, M.; Lanata, C.; Villar, E. The Interaction of Public Assets, Private Assets and Community Characteristics and its Effect on Early Childhood Height-for-Age in Peru; Young Lives: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moestue, H.; Huttly, S. Adult Education and Child Nutrition: The Role of Family and Community. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, K.A.; Brennan, A.T.; Behrman, J.R.; Schott, W.; Crookston, B.T.; Humphries, D.L.; Penny, M.E.; Fernald, L.C. Does Household Access to Improved Water and Sanitation in Infancy and Childhood Predict Better Vocabulary Test Performance in Ethiopian, Indian, Peruvian and Vietnamese cohort studies? BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumm, R.; Aßmann, C. Community-Based Clustering of Height in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2018, 167, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiadis, A. The Sooner the Better but It’s Never too Late: The Impact of Nutrition at Different Periods of Childhood on Cognitive Development; Young Lives: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, T.A. Multilevel Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Twisk, J.W. Applied Multilevel Analysis: A Practical Guide for Medical Researchers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul, J.J. Community, Culture and Sustainability in Multilevel Dynamic Systems Intervention Science. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 43, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trickett, E.J.; Beehler, S.; Deutsch, C.; Green, L.W.; Hawe, P.; McLeroy, K.; Miller, R.L.; Rapkin, B.D.; Schensul, J.J.; Schulz, A.J. Advancing the Science of Community-Level Interventions. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children: Reimagine the Future Innovation for Every Child; United Nation’s Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Young Lives: An International Study of Childhood Poverty. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08b90e5274a27b2000c05/YoungLives-Round2-OverallFindings.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Outes-Leon, I.; Dercon, S. Survey Attrition and Attrition Bias in Young Lives; Young Lives: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, I.; Ariana, P.; Petrou, S.; Penny, M.E.; Galab, S.; Woldehanna, T.; Escobal, J.A.; Plugge, E.; Boyden, J. Cohort Profile: The Young Lives Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization; UNICEF. WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children: Joint Statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cogill, B. Anthropometric Indicators Measurement Guide; Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Working Group. Use and Interpretation of Anthropometric Indicators of Nutritional Status. Bull. World Health Organ. 1986, 64, 929. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Anthro-Software for Assessing Growth and Development of the World’s Children [Computer Program]; Version 2.0, 2006; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, L.M.; Bulheller, S.; Häcker, H. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; American Guidance Service Circle Pines: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Salkind, N.J. Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cueto, S.; Leon, J. Psychometric Characteristics of Cognitive Development and Achievement Instruments in Round 3 of Young Lives; Young Lives: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, K. How Many Rooms are there in Your House? Constructing the Young Lives Wealth Index; Young Lives: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Galab, S.; Reddy, M.G.; Antony, P.; McCoy, A.; Ravi, C.; Raju, D.S.; Mayuri, K.; Reddy, P.P. Young Lives Preliminary Country Report: Andhra Pradesh, India; Young Lives: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Young Lives. Young Lives Survey Design and Sampling in India; Young Lives: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S.; Kim, D.; Kawachi, I. Covariation in the Socioeconomic Determinants of Self Rated Health and haPpiness: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis of Individuals and Communities in the USA. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Donnell, O. Access to Health Care in Developing Countries: Breaking down Demand side Barriers. Cad. de Saúde Pública 2007, 23, 2820–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, D.; Lavy, V.; Strauss, J. Public policy and anthropometric outcomes in the Cote d’Ivoire. J. Public Econ. 1996, 61, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balarajan, Y.; Selvaraj, S.; Subramanian, S. Health Care and Equity in India. Lancet 2011, 377, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. Macro International, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–2006: India; International Institute of Population Sciences: Mumbai, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, E.; Viswanathan, H. The Rural Private Practitioner. In Service Provision for the Poor: Public and Private Sector Cooperation; Young Lives: London, UK, 2004; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C.; Dornan, P.; Lives, Y.; House, Q.E. Social Protection and Children: A Synthesis of Evidence from Young Lives Research in Ethiopia, India and Peru; Department of International Development: London, UK, 2010.

- Cueto, S. Promoting Early Childhood Development through a Public Programme: Wawa Wasi in Peru; University of Oxford, Department of International Development, Young Lives: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woldehanna, T. Productive Safety Net Program and Children’s Time Use between Work and Schooling in Ethiopia; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Do School Meals Work? Treatment Evaluation of the Midday Meal Scheme in India; Young Lives: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J.; Morenoff, J.D.; Earls, F. Beyond Social Capital: Spatial Dynamics of Collective Efficacy for Children. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1999, 64, 633–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumow, L.; Vandell, D.L.; Posner, J. Perceptions of Danger: A Psychological Mediator of Neighborhood Demographic Characteristics. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1998, 68, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caughy, M.O.B.; Hayslett-McCall, K.L.; O’Campo, P.J. No Neighborhood is an Island: Incorporating Distal Neighborhood Effects into Multilevel Studies of Child Developmental Competence. Health Place 2007, 13, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCulloch, A.; Joshi, H.E. Neighbourhood and Family Influences on the Cognitive Ability of Children in the British National Child Development Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarrett, R.L. Successful Parenting in High-Risk Neighborhoods. Future Child. 1999, 9, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furstenberg, F.F.; Belzer, A.; Davis, C.; Levine, J.A.; Morrow, K.; Washington, M. How Families Manage Risk and Opportunity in Dangerous Neighborhoods. Sociol. Public Agenda 1993, 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level 1: Multivariate Outcomes | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height-for-age (z-score) | −1.5 | 1.0 | |

| Weight-for-age (z-score) | −1.9 | 1.0 | |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (z-score) | −0.01 | 1.0 | |

| Mathematics test (z-score) | −0.001 | 1.0 | |

| Level 2: Individual Characteristics (n = 1625) | N | % | |

| Sex | Boys | 968 | 53.1 |

| Girls | 856 | 46.9 | |

| Ethnicity | Scheduled castes | 325 | 17.8 |

| Scheduled tribes | 233 | 12.8 | |

| Backward castes | 882 | 48.4 | |

| Other categories | 384 | 21.1 | |

| Caregiver’s education | No education | 984 | 53.9 |

| Primary | 782 | 42.9 | |

| Post-secondary or above | 58 | 3.2 | |

| Family structure | Living with both parents | 1789 | 98.1 |

| Living with single or no parent | 35 | 1.9 | |

| Birth order | First | 703 | 38.5 |

| Second | 712 | 39.0 | |

| Third or later | 409 | 22.4 | |

| Mother’s age at birth | 20 or below | 551 | 30.2 |

| 21–30 | 1175 | 64.4 | |

| 31 or above | 98 | 5.4 | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age in months | 95.8 | 3.8 | |

| Mother’s height | 151.4 | 6.1 | |

| Wealth index | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| Level 3: Community characteristics (n = 94) | Mean | SD | |

| Local pollution problems | 2.7 | 1.7 | |

| Local social problems | 1.8 | 1.1 | |

| Access to local services | 11·5 | 4.1 | |

| Local programs run by government and NGO/charity | 27.9 | 7.1 | |

| Local healthcare resources | 2.1 | 2.6 | |

| HAZ | WAZ | PPVTZ | MATHZ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |

| Community-level variables | ||||||||

| Local pollution problems | −0.001 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Local social problems | −0.003 | 0.03 | −0.001 | 0.02 | 0.002 | 0.04 | −0.08 * | 0.04 |

| Access to local services | −0.004 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.01 |

| Local programs run by government and NGO/charity | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.0004 | 0.004 | 0.01 * | 0.01 | 0.02 ** | 0.01 |

| Local healthcare resources | 0.04 ** | 0.01 | 0.03 * | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Individual-level variables | ||||||||

| Age (in months) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.08 *** | 0.02 | 0.07 *** | 0.02 | 0.11 *** | 0.02 |

| Sex (reference: girls) | ||||||||

| Boys | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.16 *** | 0.04 | 0.27 *** | 0.04 | 0.08 * | 0.04 |

| Ethnicity (reference: Backward castes) | ||||||||

| Scheduled castes | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Scheduled tribes | −0.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.28 *** | 0.08 |

| Other categories | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.22 *** | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Caregiver’s education (reference: no education) | ||||||||

| Primary or below | 0.13 * | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.17 *** | 0.05 | 0.33 *** | 0.05 |

| Post-secondary or above | 0.33 * | 0.14 | 0.44 ** | 0.14 | 0.52 *** | 0.13 | 0.66 *** | 0.13 |

| Family structure (reference: living with both parents) | ||||||||

| Living with single or no parent | −0.07 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.29 * | 0.14 |

| Birth order (reference: first) | ||||||||

| Second | −0.12 * | 0.05 | −0.11 * | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.05 |

| Third or greater | −0.36 *** | 0.06 | −0.37 *** | 0.07 | −0.22 *** | 0.06 | −0.22 *** | 0.06 |

| Mother’s age at birth (reference: 20 or below) | ||||||||

| 21–30 | 0.20 *** | 0.05 | 0.17 *** | 0.05 | 0.19 *** | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| 31 or above | 0.37 *** | 0.11 | 0.23 * | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Mother’s height | 0.24 *** | 0.02 | 0.16 *** | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Wealth index | 0.18 *** | 0.03 | 0.21 *** | 0.03 | 0.18 *** | 0.03 | 0.21 *** | 0.03 |

| Random Effects | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Level 3 (Community) | ||||||

| HAZ | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| WAZ | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| PPVTZ | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| MATHZ | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Level 2 (Individual) | ||||||

| HAZ | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.03 |

| WAZ | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.03 |

| PPVTZ | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.03 |

| MATHZ | 0.76 | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.66 | 0.02 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPVTZ | MATHZ | PPVTZ | MATHZ | PPVTZ | MATHZ | |

| Level 3 (Community) | ||||||

| HAZ | 0.095 (0.024) | 0.098 (0.026) | 0.012 (0.011) | 0.001 (0.012) | 0.017 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.010) |

| WAZ | 0.117 (0.025) | 0.100 (0.026) | 0.028 (0.011) | 0.008 (0.011) | 0.029 (0.010) | 0.010 (0.017) |

| Level 2 (Individual) | ||||||

| HAZ | 0.126 (0.021) | 0.188 (0.020) | 0.088 (0.019) | 0.129 (0.018) | 0.086 (0.019) | 0.129 (0.018) |

| WAZ | 0.126 (0.022) | 0.179 (0.021) | 0.098 (0.020) | 0.129 (0.019) | 0.097 (0.020) | 0.129 (0.019) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPVTZ | MATHZ | PPVTZ | MATHZ | PPVTZ | MATHZ | |

| Level 3 (Community) | ||||||

| HAZ | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| WAZ | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| Level 2 (Individual) | ||||||

| HAZ | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| WAZ | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heo, J.; Krishna, A.; Perkins, J.M.; Lee, H.-y.; Lee, J.-k.; Subramanian, S.V.; Oh, J. Community Determinants of Physical Growth and Cognitive Development among Indian Children in Early Childhood: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010182

Heo J, Krishna A, Perkins JM, Lee H-y, Lee J-k, Subramanian SV, Oh J. Community Determinants of Physical Growth and Cognitive Development among Indian Children in Early Childhood: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(1):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010182

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeo, Jongho, Aditi Krishna, Jessica M. Perkins, Hwa-young Lee, Jong-koo Lee, S.V. Subramanian, and Juhwan Oh. 2020. "Community Determinants of Physical Growth and Cognitive Development among Indian Children in Early Childhood: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 1: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010182

APA StyleHeo, J., Krishna, A., Perkins, J. M., Lee, H.-y., Lee, J.-k., Subramanian, S. V., & Oh, J. (2020). Community Determinants of Physical Growth and Cognitive Development among Indian Children in Early Childhood: A Multivariate Multilevel Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010182