Abstract

Sustainability needs the socially responsible orientation of public institutions, but not only externally. How civil servants and municipal employees consider what local governments do in relation to their internal social responsibility is the main question of this study. Through structural equation modelling and a sample of 294 employees in local governments in a Spanish region (Extremadura), it is demonstrated that responsible job position design, as well as good communication and team building, both have positive and significant effects on the personal identification of employees with the city council. That has been interpreted as the essence of internal social responsibility and the first step for building external social responsibility at the municipal level. Practical implications and future directions are discussed.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is a global goal that implies meeting the needs of present generations without putting in danger the capacity of future generations to satisfy their own needs [1]. This means that sustainable organizations, private or public, have to seek the best conditions for life for everyone at present, and also for the coming generations [2,3]. In this context, the role adopted by the social responsibility (SR) of organizations is the obligation to reach maximum levels in their positive impacts on stakeholders, and to reduce as much as possible the negative ones [4].

In this context, SR is increasingly required not only of the private sector, but also of the public sector, whose main traditional functions are to provide accessible and qualitative service delivery, commercial activities, and stewardship of public assets to satisfy society (and not principally to obtain financial reward) [5]. At first glance, SR and sustainability are mainly linked to traditional public sector values, such as empathy, solidarity, fairness, integrity, or accountability [6,7]. In addition, SR is needed more than ever in the public sector, which has evolved from service delivery to co-production [8]. That means that government organizations are appealing to the intrinsic needs and social values of citizens. Under this new paradigm for understanding the public sector, it is expected going forward that available resources will be used effectively and efficiently, and new practices are gaining relevance. We refer to the emergence of collaborative government, public–private partnerships, or network governance [9,10,11,12].

In this complex context, in order to face the rapid evolving world, SR in local governments has to respond to new challenges that are emerging for public institutions. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are not yet substantial and relevant works devoted to the study and analysis of SR in public administrations and the relationship with their stakeholders.

Some related works approach citizens as a specific stakeholder in city councils, showing the external face of public SR. For instance, and under the theoretical framework developed by Osborne and Gaebler [13], citizens are considered as clients or customers. The focus of government policies and operations placing citizens as the central focus when designing public service delivery emphasizes concerns and needs. However, the movement, called “reinvented government administration”, has been questioned by other authors, such as Carroll [14], arguing that turning citizens into consumers marginalizes citizenship rather than activating participation. Other authors, such as Frederickson [15], have criticized the treatment of citizens as consumers, because citizens are really owners. Whatever it is, the SR of local governments under different approaches is undoubtedly a subject of debate.

In relation to the internal face of SR that considers employees as relevant stakeholders, it is true that human resource management (HRM) is increasing the attention of public management research. For instance, some studies have analyzed the HRM function in the public sector in relation to employee outcomes, such as job satisfaction or employee commitment [16,17], motivation [18,19,20], or public sector performance [21,22]. There is also a specific field of research devoted to comparing HRM in the private and public sectors [23,24,25,26]. In the same vein, an emergent body of academic literature exists on how the best HRM practices, called high-performance work practices (HPWP) [27,28], interrelate with each other and contribute to business performance [29,30], and some attempts exist to approach HPWP in public services [31], or even in local governments [32]. There are also studies linking HPWP to SR [33].

However, the reality is that there are not yet significant movements or relevant studies about internal SR in the public sector in general, and there are a lack of studies about the internal side of SR in local governments. To contribute to fill the gap, how civil servants and municipal employees consider what local governments do in relation to their internal social responsibility is the main question of this study. For that purpose, this paper deals with the development of a model to approach the SR of municipalities with civil servants and municipal employees.

2. Theoretical Background: Internal Social Responsibility in Local Governments

The stakeholder theory holds that besides shareholders, other groups are affected by an organization’s activity, and have to be also considered in managers´ decisions [34]. From this perspective, the collective efforts of the stakeholder network are at the core of value creation of any organization [35]. According to this theory, and following Sánchez-Hernández et al. [36], we can say that SR considers two different groups of stakeholders.

First, external SR considers the relationship of organizations with their communities. Organizations interact with their external stakeholders when they provide products or services by guaranteeing economic activity. That implies responsible actions, such as paying taxes, investing in the local economy, respecting human rights, and preserving the environment. Second and not less important, but still understudied, SR has an internal face that put the emphasis on employees. This internal consideration of SR adds a new perspective to the discussion about organizational management for sustainable development, by acknowledging that it is impossible to be socially responsible without a sound relationship with internal stakeholders. This mix of stakeholders and internal and external interacting with each other could be more or less sustainable when providing resources to the economic system, benefiting from the organization, and impacting the environment [37].

In recent years, HRM is starting to play a significant and helpful role in SR in organizations [38]. However, in contradiction, employees are still neglected stakeholders when conducting SR activities [39]. In the case of public organizations in general, and local governments in particular, the consideration of employees as internal stakeholders might be especially relevant, because these institutions have the duty to perform well, and to be good examples for different stakeholders, including their employees [40]. According to Mason and Simmons [41], employees expect SR values from their employing organization to be similar to other stakeholders, arguing that employees seek economic, functional, psychological, and ethical benefits from them. Consequently, if employers create, design, and offer stimulating work positions, some functional benefits will be obtained, and it will also be perceived as indicative of a socially responsible employer and a main driver of internal SR [42]. Thus, at the local government level, civil servants and municipal employees should be an important stakeholder to be considered. At this respect, it has been noted that civil servants and municipal employees have lower levels of motivation and satisfaction than private sector employees [43]. Boog and Cooper [44] also found that civil servants suffered more mental and physical illness. The main factors were intrinsic to the public job position, such as inequity regarding reward conditions and the feeling of having little control over their job and their institution.

Social identity theory is about individuals in groups, and the nature of social group processes. Since their origins, social identity has been seen as a social process [45]. The theory focuses on how identification works individually, how interactions are, and how these interactions impact on institutions [46]. It explains the role of self-conception, the associated cognitive processes, and the benefits for being part of a social group, including intergroup relations [47]. The central assumption of social identity theory is that group members will develop self-esteem, trust, and engagement, thus enhancing their external image [48].

Thus, civil servants, as individuals and municipalities, as organizations or social groups, are two sides of the same coin. Fostering social identification should improve the external image of municipalities.

Organizational identification refers to the degree to which someone defines himself (or herself) as having the same characteristics or traits that he (or she) believes define this organization [49]. Moreover, it is not a simply top-down shaping of the individual. According to Kuhn and Nelson [50], you are identified to your organization after an attaching process of shaping the organizational identities. Thus, organizational identification goes beyond job engagement [51] or organizational commitment [52]. In the context of local governments, we consider that the organizational identification of employees with their city council is the expected result of a successful internal SR. For instance, the expected public organization´s commitment to fairness and responsibility is reflected in designing jobs according to an equal opportunity philosophy. Discrimination between civil servants and municipal workers cannot exist, nor can any kind of discriminatory behavior at work because of sex or religion, among others [53].

To sum up, responsible local governments must be oriented to link HRM and SR development. For that purpose, human resource strategies must be redefined for considering new topics in public institutions, such as health prevention and safety at work, lifelong training programs, challenging systems of internal communication, and performance management systems, among others [54,55,56].

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. The Importance of Designing Responsible Job Positions

Without underestimating other relevant issues related to the internal side of SR in any organization, and on the basis of responsible HRM, we want to highlight the relevance of a responsible job design (RJD). Unfortunately, the term RJD is not strongly embedded in academic literature at the moment, and neither is the term internal SR. Tangentially, some studies confront the good SR consideration of some companies when they have a bad reputation as employers. That has been the case with McDonald´s [57] and France Telecom [58], for instance. In these cases, where external SR is not balanced with internal SR, the organization is at risk of being accused of dishonesty and the SR should be considered as artificial.

Some authors have stated that job design essentially involves integrating job qualifications and responsibilities that are required to perform it [59].

In line with academic literature devoted to study ethics and the meaning of work [60,61,62], but also acknowledging the importance of traditional theories of work motivation and work design [63], RJD covers several dimensions, such as equal opportunities, well-paid work, salary in line with functions, recognition to the best suggestions and projects, autonomy at work, positive appreciation of the employee ideas by managers, and a responsible way of determining the worth of jobs, including a fair evaluation of employee performance. Along these lines, and considering that all existing measures are somehow incomplete, the scale developed by Morgeson and Humphrey [63], for instance, offers a set of indicators that are useful for approaching a socially responsible design.

Although there is no consensus among researchers about the particular human resource practices that are the most consistent with the sustainability approach, Thom and Zaugg [64] have argued that performance pay is one of the essential elements. This notwithstanding, well-paid work is one of the hot issues the public and private sectors are facing in the whole world. The importance of the mentioned issue is reflected in numerous ways. For instance, wages are included in the job quality index [65], or decent work concept, introduced by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), underlining the need for fair income. Well-paid work can reveal the level of care for employees provided by the employer, as our living quality standard is partly associated with the amount of money people earn. Moreover, a high level of pay can ensure that private and public sectors are able to attract and retain highly qualified employees [66]. Thus, the expected care of city councils for civil servants and municipality workers in terms of well-paid work indicates a responsible work design.

Salary in line with the employee’s functions emphasizes payment according to individual performance. Without underestimating different approaches concerning pay schemes in a public sector [67], we defend that local governments can elicit a certain level of performance from civil servants and municipal employees, by linking pay with functions and degree of responsibility. However, in this respect, Buurman et al. [68] found that only 45% of employees in the public sector in the Netherlands considered their salary to be adequate for the work they did. These findings do not fit the internal SR and opens the avenues for improving the job design.

Recognition of the best suggestions and projects is also an essential element of an RJD. According to the work psychodynamics theory, recognition is a reward expected by the subject that is largely symbolic in nature [69]. Mostly, recognition stems from a judgment made about various aspects. Thus, employee recognition can be expressed through four practices: personal recognition, recognition of work practices, recognition of job dedication, and recognition of results [69]. As stated by Saunderson [70], employee recognition in the public sector strongly correlates with good morale, loyalty, commitment, and satisfaction in the workplace. Moreover, recognition of employees serves as critical tool for their retaining. Bearing in mind that in the mentioned findings, it is supposed that the recognition of civil servants and municipal employees for the best suggestions and projects will increase the responsibility of any job design.

Morgesson and Humphrey [63] argue that nowadays, autonomy at work reflects the extent to which a job allows freedom, independence, and discretion to schedule work, make decisions, and choose the methods used to perform tasks. Freedom of civil servants and municipal employees in three domains, namely work scheduling, decision making, and work methods, strengthens the employee voice and participation [71].

Positive appreciation of employee ideas by managers is reflected in designing jobs according to the perceived manager support idea. Chughtai and Zafar [72] have emphasised that supervisors play an essential role in the employee–employer relationship. Results from previous studies give us an idea about the importance of support by the superiors of public employees [73]. Managers influence employee perceptions about the local government’s supportiveness. Moreover, managers have an impact on the extent to which employees can expect that the organization will look after their interests, i.e., behave in a socially responsible way.

Socially responsible organizations must attend to the fit of employees with the values of the organization [74]. Consequently, job evaluation, as the judgment about value or worth of the jobs, might be a feature of responsible work places. A responsible job evaluation begins with the analysis of work to determine its characteristics and requirements, and then follows with fair employee performance management. Employee performance evaluation is related to goal setting and providing feedback. As stated by Verbeeten [75], by setting clear goals and “measuring whether they are achieved, organisations reduce and eliminate ambiguity and confusion about objectives, and gain coherence and focus in pursuit of their mission”. The expected local government commitment to the fair evaluation of employee performance is reflected in designing jobs in line with the organisational justice philosophy. It is supposed that procedural, interactional, interpersonal, and informational justice dominate in a responsible work design [76].

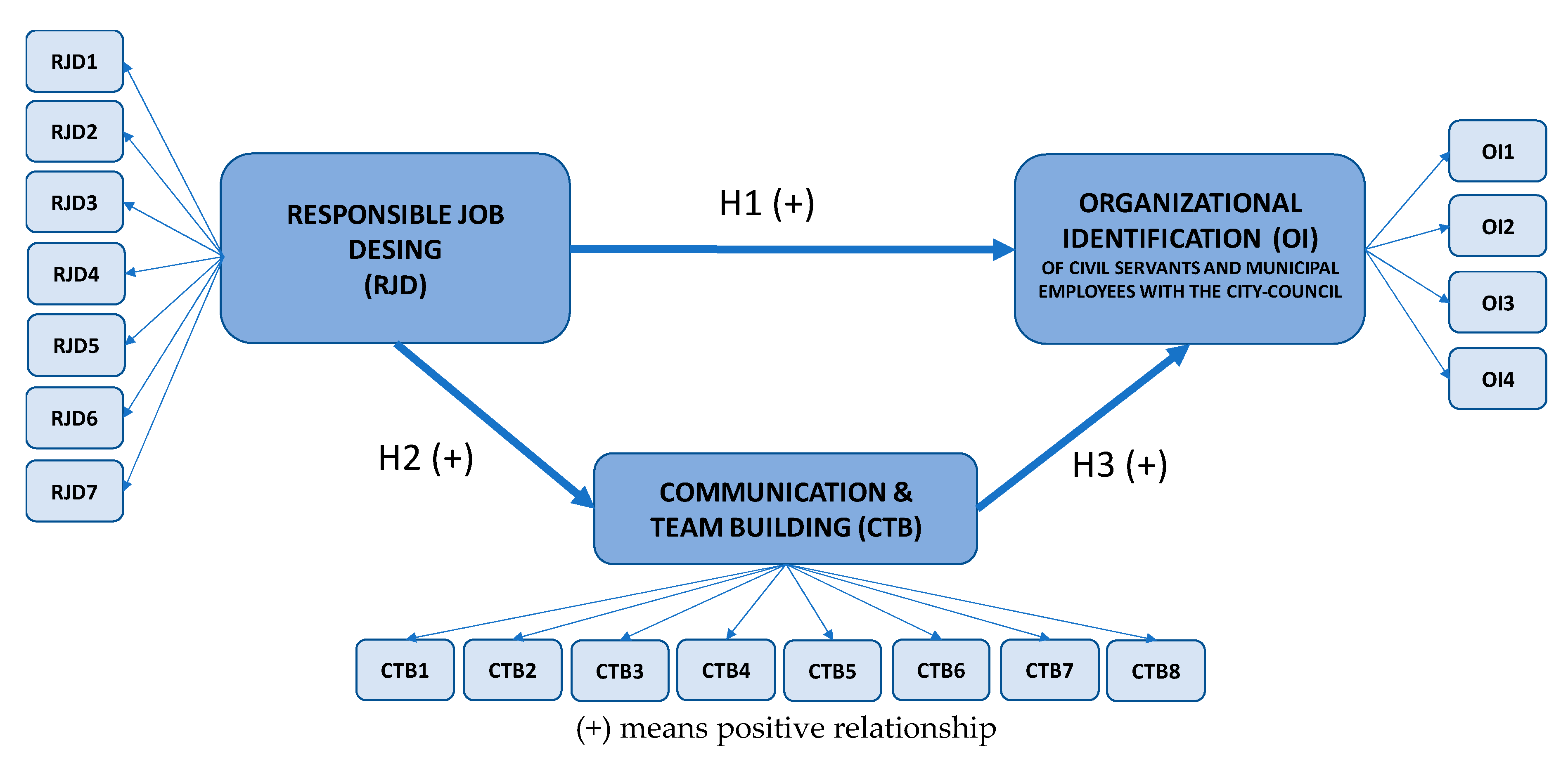

A responsible design of job positions in public institutions is expected to be linked to higher levels of organizational identification of employees with their city council. The better the jobs are designed, the higher the level of identification will be. In the same vein, the better the communication and team building efforts are, the higher the personal identification of employees will be with the city council where they work. Taking into consideration all the above, the following hypothesis emerges:

Hypothesis (H1).

The responsible design of jobs in local governments is positively related to the employee´s identification with the city council.

3.2. The Role of Communication and Team Building

RJD is not enough for developing an effective internal SR. Communication and team building play an essential role in allowing things happen. At its simplest, communication could be defined as social interaction through messages [77,78]. In a huge part of literature, the significant role of organizational communication (internal and external) is acknowledged as it persists throughout the lifespan of the organisation [79].

From the perspective of the internal side of SR in any organization, internal communication is a matter of interest following evidence that the outcomes of effective internal communication are beneficial for both sides: the whole organization and employees as stakeholders. For instance, Welch and Jackson [80] stated that effective internal communication influences employee productivity and the behaviour of the organization. Thomas et al. [81] argued that communication plays an essential role in the development of trust within any organisation, and Martin-García and Conci [82] highlighted that informal participation and communication are considered as frequent HPWP in countries such as Spain. Going further, we can affirm that effective internal communication enables the success of teambuilding and teamwork [83]. Recently, teamwork has been getting more interest, assuming that integrated teamwork is more important than individual work in reaching organizational goals [84].

Communication and teambuilding are very important in public institutions [85,86]. Effective internal communication is crucial for success, as it affects the ability of managers to engage employees and achieve objectives [87]. Moreover, internal communication is designed to promote commitment to the organization, a sense of belonging to it, awareness of its changing environment, and understanding of its evolving aims [80]. Effective communication supports teamwork, and team relations appear to be an important motivator for public employees [63]. Communication pathways and channels or teambuilding are supposed to have positive relationships with job design and the personal identification of employees. Finally, and taking into consideration all the above, the following hypotheses emerge:

Hypothesis (H2).

The responsible design of jobs in local governments is positively related to communication and team building developments.

Hypothesis (H3).

Communication and team building efforts are positively related to the employees’ identification with the city council.

4. Method

4.1. Tools

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was considered adequate to test the hypotheses of this study. According to Fornell and Larcker [88], SEM shows cause–effect relationships between constructs. SEM modeling distinguishes two different approaches, assuming that one method is not superior to the other. Sometimes SEM is equivalent to carrying out covariance-based analyses, using software like LISREL for instance. Our approach is different. We used partial least squares (PLS), which is a causal modeling approach aimed at maximizing the explained variance of the dependent latent constructs [89,90].

PLS-SEM has as the main characteristic of having higher statistical power, and this is quite useful for research that examines still-developing theory [91,92], as it is in our case. In addition, we have used the original PLS algorithm, because the aim is definitely exploratory but somehow predictive, and in both cases it is recommended by authors like Sarsted et al. [93] to use composites instead of common factor.

This methodological tool has the capacity to confront theory and data through a system of multiple regressions between constructs. In our study, there are three latent variables to be analyzed: RJD, communication and team building, and the employees´ identification with the city council. The three constructs are latent variables, not directly observable ones that need indicators (observable variables) to be approached, as will be shown later.

In this study, we have used the software Smart-PLS (Partial Least Squares), developed by Ringle et al. [94]. The estimation of parameters is based on minimizing the residual variances of the endogenous variables and maximizing the explained variance (R2) of the dependent variables.

4.2. Measurement Scales

Previous literature review has served the purpose of defining a selection of items approaching RJD, communication, and team-building. The organizational identification of civil servants and municipal employees with the city council is in line with the SR and sustainability framework. Social identity theory argues that people classify themselves as belonging to various social categories according to interests, skills, age, etc. [95]. Having an organizational context in mind, most research deals with employee identification with a particular team, workgroup, department, occupation, and organisation [96]—in this case, the identification with the city council. In this work, the construct has been approached from the field of marketing, following Mael and Ashforth [97]. To sum up, and supported by the literature review, the selected indicators for this study are shown in Table 1, as follows.

Table 1.

Measurement tool.

4.3. Procedure and Sample

An empirical study was carried out to contrast the hypotheses derived from the model and validate them for the region under study. It is important to note the difficulty for accessing employees, as official procedures were numerous and red tape was a barrier for field work. That was the reason for using a nonprobability sampling, in which employees were sampled because they were accessible sources of data for researchers.

In total, 294 participants, civil servants, or municipal employees from an initial population of 1200 employees from 12 different city councils in the Autonomous Region of Extremadura answered a questionnaire, with five-point Likert questions measuring the variables with the selected indicators. The technical data sheet is shown in Table 2. No distinction was made between civil servants and municipal employees, because their labor situations were not linked to specific roles or functions.

Table 2.

Technical data sheet.

4.4. Model

The theoretical model developed (Figure 1) represents the expected relationship between RJD, on the basis of the internal SR of the city council, and the expected positive impact on the organizational identification of civil servants and municipal employees with the city council. In a local government, internal SR should start by designing responsible jobs for employees to guarantee the process of shaping the desired responsible city council identity to which public employees attach. The model also considers the mediating role of communication and teamwork in enabling the process.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

5. Results

Firstly, we present results from the measurement model (the “inner model”). For evaluating the measurement model, we calculated reliability, which is an attribute considering whether the process is stable and consistent [98]. It is the first step in reflective measurement model assessment, and involves examining the indicator loadings. Loadings above 0.7 are recommended, as they indicate that the construct explains more than 50% of the indicator’s variance, thus providing acceptable item reliability [92]. This attribute was assessed by examining simple correlations of the measures with their respective latent variables. Considering the exploratory nature of the study, a value with 0.64 was accepted. Table 3 shows the loadings of each observed variable, demonstrating that depuration of items was not needed.

Table 3.

Loadings.

Table 4 analyzes and confirms that our constructs were properly measured by the indicators. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used as an index of reliability of the latent variables. Composite reliability was also calculated. Validity was also considered, which is an attribute measuring what one really wanted to measure [98]. The convergent validity of each construct was evaluated through the average variance expected (AVE) (accepted when >0.5). The discriminant validity of constructs was verified using the Fornell–Larcker criterion [99] when examining whether the square root of the AVE value of each item was above the correlations with the other latent variables. In addition, according to Henseler et al. [100], a test was conducted to demonstrate whether another technique better detects the potential lack of discriminant validity: the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) relationship test. Discriminant validity was also confirmed, as HTMT ratios for each pair of factors were <0.90 [100].

Table 4.

Inner model results.

Secondly, we carry out the analysis of the structural model (“outer model”) for verifying whether the model considers the proposed relationships between the constructs. For this purpose, the path coefficients (β) were examined, along with their respective levels of significance. Although PLS estimators lack the parameter precision of maximum-likelihood estimation in achieving optimal prediction, we provided values for R2 (the explained variance of the endogenous variables), and the root mean square residual (SRMR), even acknowledging that it is only necessary for confirmatory composite analysis [101]. The overall fit of the model was evaluated using the standardised root mean square residual indicator (SRMR). Hu and Bentler [102] defined SRMR as the root mean square difference between the correlations observed and the correlations implicit in the model. A cut-off value of 0.08 for SRMR is considered the most appropriate in PLS [103]. In this study, the SRMR was 0.078, which means that the model fits the empirical data [98].

Taking into account that the principal usefulness of the PLS methodology is to predict potential cause–effect impacts between constructs into a model, the goodness of a model is mainly determined by the strength of each structural path, and is analyzed using the value of R2 (explained variance) for the dependent latent variables. The values of R2 obtained for research has led to the following conclusions: 0.67 is considered to be good, 0.33 is medium, and 0.19 is weak [104]. The result obtained for the principal dependent variable in the model organizational identification (OI) was R2 = 0.47 The evidence, therefore, shows that the presented model has a substantial predictive capacity. This explains why both the RJD and communication and team-building (CTB) contribute decisively to a successful OI.

The predictive relevance of the model was also studied through the blindfolding technique, and it demonstrates that the model has predictive capacity. This technique consists of omitting part of the data of a given construct during the estimation of the parameters, and then trying to estimate what was excluded from the estimated parameters [104]. According to the results obtained (Q2 (Predictive relevance measure in PLS) for CTB = 0.340 and Q2 for RJD = 0.251) all endogenous constructs fulfil Q2 > 0. Following the Stone–Geisser (Q²) test [105,106], the values are 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, indicating small, medium, and high predictive relevance, respectively. As a result, both the CTB and RJD constructs have medium–high predictive relevance.

Complementary to htis, PLSpredict was calculated following Hair et al.’s procedure [107] (Table 5). Setting k (k is the default number of equally sized subsets of data) = 10, Q2predict values >0 indicate that the model outperforms the most naïve benchmark. Comparing the root mean squared error values (RMSE) with the linear regression model value (LM) of each indicator, we found that the majority of the indicators presented RMSEPLS < RMSELM, corroborating the medium–high predictive power of the model.

Table 5.

PLSprediction summary.

Finally, the bootstrapping procedure was used for hypotheses testing (Table 6). Bootstrapping is a non-parametric resampling procedure that assesses the variability of a statistic by examining the variability of the sample data [108]. The results obtained allow the accepting all the hypotheses, since there were no statistically significant differences in the relationships between the variables in our model (value of p > 0.05).

Table 6.

Hypotheses testing.

6. Discussion

Sustainable development (people, planet, and profit) must be addressed from private organizations, but also from public entities, and city councils are an important part of those. This work contributes to both the theoretical and empirical literature within SR in the public sector. In terms of theory, the paper contributes to the literature on SR, revealing the relevance of the internal side related to HRM in general and HPWP in particular. Moreover, the paper adds value to the state-of-the-art of literature approaching the internal SR of municipalities and including the perception of civil servants and municipal employees, using a new set of variables that are specifically suited to the public sector at the local level.

Considering the lack of previous studies devoted to this topic and the exploratory nature of this pilot study to approach the internal responsibility of city councils, we have put the attention on RJD according to the civil servants and municipal employees´ perceptions and the linkages to their social identification. The novelty of the article is twofold: first, the conceptualization of the term RJD, and second, the empirical exploration of the latent variables of this construct under the social identity theory.

7. Conclusions

The emphasis on RJD as the basis of internal SR in the context of city councils provides a novel and specific context for the analysis of the emerging issue of HPWP in the public sector, and shifts the emphasis away from the traditional general studies comparing private and public HRM [23,24,25,26]. This article simultaneously addressed the application of HPWP in the public sector for engaging employees to their institutions. Thus, we can conclude that the adoption of RJD as an HPWP in city councils provides a mechanism whereby local governments can consider their internal SR as strategic for sustainable improvement and performance [27].

The paper provides also some practical implications for public policy at the local level that could be considered future lines of research. First, it would be valuable to further examine how civil servants and municipal employees construct their identification with the city council, and how this impacts their performance, and eventually, the citizens´ satisfaction. Secondly, and directly related, an area that deserves practical attention is exploring the opportunities that exist for linking internal and external SR in public institutions. Broadly speaking, there is a deficit of connection between HRM/HPWP and external public policies for enhancing sustainability and related issues.

Thus, in line with the scarce previous works [31,32,33], and taking into consideration the results obtained from the empirical study, we can conclude the following: high-performance-work city councils could be described as local governments with high levels of internal RS that are putting the emphasis on RJD, internal communication, and team development to guarantee engaged and empowered civil servants and municipal workforces, who are very identified with the council and offer high-quality goods and services.

The paper has some limitations that will have to be overcome in future research—primarily, the use of data from a region in a single country. This study will be extended to other regions in Spain, but also to other regions in other countries, in order to get insights from different contexts and to refine the model for a better and more generalizable understanding of the internal side of SR in local governments.

Another relative limitation is the fact that the design of the study was not longitudinal. SEM-PLS is specially recommended for empirically testing theoretical cause–effect processes [91,92,93], and the results obtained from the new function PLSpredict [108] satisfactorily confirm the predictor power of the model tested.

However, new studies are needed in this line of research. The purpose here was only exploratory, and that was the reason to use PLS and composites, as recommended by Sarstedt et al. [93], acknowledging that it was not clear whether SR, RJD, and OI were composites or common factors. The good results obtained both in the measurement and structural model promote continuing in this line of research and looking for more explicative and complex models in the near future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I.S.-H. and Ž.S.; methodology, M.I.S.-H.; formal analysis and data curation M.I.S.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.S.-H.; writing—review and editing, M.I.S.-H., Ž.S., R.R.-R., and C.D.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Social Fund through the Autonomous Region of Extremadura, V Research Plan, Research Group SEJ021, and grant number IB16024.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the participation of Local Public Administrations in Extremadura.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C. Value maximization, stakeholder theory, and the corporate objective function. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2001, 14, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J.; Freeman, E.; Schaltegger, S. Applying stakeholder theory in sustainability management: Links, similarities, and a conceptual framework. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Fraedrich, J.; Ferrell, L. Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making and Cases; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.; Marsden, P.; Reynolds, J.; Knoke, D. Beyond profit? Sectoral differences in high-performance work practices. Work Occup. 2006, 33, 271–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.T.; Duxbury, L.E.; Higgins, C.A. A Comparison of the values and commitment of private sector, public sector, and parapublic sector employees. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wal, Z.; De Graaf, G.; Lasthuizen, K. What’s valued most? Similarities and differences between the organizational values of the public and private sector. Public Adm. 2008, 86, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, J. Engaging Public Sector Clients: From Service-Delivery to Co-Production; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Agranoff, R.; McGuire, M. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, C. The Essential Public Manager; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. The Art of Public Strategy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gazley, B. Why not partner with local government? Nonprofit managerial perceptions of collaborative disadvantage. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2010, 39, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, D.; Gaebler, T. Reinventing Government. How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.D. The rhetoric of reform and political reality in the national performance review. Public Adm. Rev. 1995, 55, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, H.G. Comparing the reinventing government movement with the new public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 1996, 56, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould-Williams, J. The effects of ‘high commitment’ HRM practices on employee attitude: The views of public sector workers. Public Adm. 2004, 82, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould-Williams, J.; Davies, F. Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes: An analysis of public sector workers. Public Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.A. A motive to serve: Public service motivation in human resource management and the role of PSM in the nonprofit sector. Public Pers. Manag. 2006, 35, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L. Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2008, 38, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Anderfuhren-Biget, S.; Varone, F. HRM practices, intrinsic motivators, and organizational performance in the public sector. Public Pers. Manag. 2013, 42, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Smith-Walter, A. The relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance in the public sector: Focusing on mediating roles of work attitudes. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 18, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.B.; Boesen, A.; Pedersen, L. Performance in Public Organizations: Clarifying the Conceptual Space. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, G.; Poole, M.; Jenkins, G. Human resource management in the public and private sectors: An empirical comparison. Public Adm. 1999, 77, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, G.H.; Tzafrir, S.S. HRM practices in the public and private sectors: Differences and similarities. Public Adm. Q. 2001, 25, 316–355. [Google Scholar]

- Bellou, V. Shaping psychological contracts in the public and private sectors: A human resources management perspective. Int. Public Manag. J. 2007, 10, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Y.; Davis, A.J.; Van Dick, R. Organizational commitment profiles and job satisfaction among Greek private and public sector employees. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2007, 7, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamkin, P. High Performance Work Practices; Institute for Employment Studies: Brighton, UK, 2004; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Antonioli, D.; Mancinelli, S.; Mazzanti, M. Is environmental innovation embedded within high-performance organisational changes? The role of human resource management and complementarity in green business strategies. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, D.M.; Ferris, G.R.; Van Iddekinge, C.H. Line manager implementation perceptions as a mediator of relations between high-performance work practices and employee outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbonnaya, C.; Valizade, D. High performance work practices, employee outcomes and organizational performance: A 2-1-2 multilevel mediation analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, S.; Kessler, I.; White, G.; Harris, L. UK public sector reform and the “performance agenda” in UK local government: HRM challenges and dilemmas. Pers. Rev. 2005, 34, 681–696. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, J.J. The development of human resource management in quality award winning governments. J. Organ. Excell. 2002, 21, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Khalid, A. High-Performance Work Practices and Environmental Social Responsibility of Firm: Mediatory role of Individually Perceived Stress. Psychology 2019, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder Theory and ‘The Corporate Objective Revisited’. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, C.; Tsitsianis, N.; Andersson, T.; Gleadle, P. Accounting for business models: Increasing the visibility of stakeholders. J. Bus. Models 2015, 3, 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Barcik, A.; Dziwiński, P. The effect of the internal side of social responsibility on firm competitive success in the business services industry. Sustainability 2016, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavan, T.N.; McGuire, D. Human resource development and society: Human resource development’s role in embedding corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and ethics in organizations. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2010, 12, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redington, I. Making CSR Happen: The Contribution of People Management; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Askim, J. Determinants of performance information utilization in political decision making. In Performance Information in The Public Sector: How It Is Used; Van Dooren, W., van de Walle, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2001; pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C.; Simmons, J. Embedding Corporate Social Responsibility in Corporate Governance: A Stakeholder Systems Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 119, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.; Leire, C. Socially responsible purchasing in supply chains: Drivers and barriers in Sweden. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniss, C.; Kale, S.J. Public sector professionals, job characteristics, satisfaction and aspirations for intrinsic fulfillment through work. Hum. Relat. 2001, 40, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogg, J.; Cooper, C. Job satisfaction, mental health, and occupational stress among senior civil servants. Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Tajfel, H. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychol. Intergroup Relat. 1986, 5, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R. Social Identity; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A. Social identity theory. In Understanding Peace and Conflict Through Social Identity Theory; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, J.B.; Marler, L.; Hester, K.; Frey, L.; Relyea, C. Construed external image and organizational identification: A test of the moderating influence of need for self-esteem. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 146, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.; Nelson, N. Reengineering identity: A case study of multiplicity and duality in organizational identification. Manag. Commun. Q. 2002, 16, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Guy, M.E. How emotional labor and ethical leadership affect job engagement for Chinese public servants. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, E.; Van Der Heijden, B.I. Organizational commitment, public service motivation, and performance within the public sector. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2007, 31, 241–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, J.R. The moral foundation of employee rights. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 24, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaupré, D.; Cloutier, J.; Gendron, C.; Jiménez, A.; Morin, D. Gestion des ressources humaines, développement durable et responsabilité sociale. Rev. Int. Psychosociol. 2008, 14, 77–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, J.; Devi, A. Corporate social responsibility: The key role of human resource management. Bus. Intell. J. 2009, 2, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Barthe, N.; Belabbes, K. La GRH socialement responsable: Un défi pour les entreprises engagées dans une démarche RSE. Manag. Avenir 2016, 1, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valax, M. Beyond McDonald’s CSR in China: Corporation perspective and report from case studies on a damaged employment reputation. Asian Bus. Manag. 2012, 11, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, M.; Gomez-Mejia, L.; Firfiray, S.; Berrone, P.; Villena, V.H. Leader beliefs and CSR for employees: The case of telework provision. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.E. Job design and employee motivation. Pers. Psychol. 1969, 22, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, J.; Martin, G.; Staines, H. Exploring the relationship between psychological contracts and organizational change: A process model and case study evidence. Strateg. Chang. 2000, 9, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S. Creating the Healthy Organization: Wellbeing, Diversity and Ethics at Work; Thompson Learning: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, S.; Holmes, N. The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2006, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, N.; Zaugg, R.J. Nachhaltiges und Innovatives Personal Management. In Nachhaltiges Innovations Management; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004; pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, K.J. Social sustainability and quality of working life. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tooksoon, H.M.P. Conceptual framework on the relationship between human resource management practices, job satisfaction, and turnover. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2011, 2, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Weibel, A.; Rost, K.; Osterloh, M. Pay for performance in the public sector—Benefits and (hidden) costs. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 20, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buurman, M.; Delfgaauw, J.; Dur, R.; Van den Bossche, S. Public sector employees: Risk averse and altruistic? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 83, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, J.P.; Dugas, N. An analysis of employee recognition: Perspectives on human resources practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunderson, R. Survey findings of the effectiveness of employee recognition in the public sector. Public Pers. Manag. 2004, 33, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, N.; Proctor-Thomson, S. ‘Workplace Sustainability and Employee Voice,’ in Readings in HRM and Sustainability, 1st ed.; Tilde University Press: Mornington, Australia, 2011; pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chughtai, A.A.; Zafar, S. Antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment among Pakistani university teachers. Appl. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2006, 11, 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Anderfuhren-Biget, S.; Varone, F.; Giauque, D.; Ritz, A. Motivating employees of the public sector: Does public service motivation matter? Int. Public Manag. J. 2010, 13, 213–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gully, S.M.; Phillips, J.M.; Castellano, W.G.; Han, K.; Kim, A. A mediated moderation model of recruiting socially and environmentally responsible job applicants. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 935–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeeten, F.H. Performance management practices in public sector organizations: Impact on performance. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, P.W., Jr.; McNall, L. Justice perceptions of performance appraisal practices. J. Manag. Psychol. 2010, 25, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, J. Introduction to Communication Studies, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kalla, H.K. Integrated internal communications: A multidisciplinary perspective. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2005, 10, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyton, J. Communication in organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.; Jackson, P.R. Rethinking internal communication: A stakeholder approach. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2007, 12, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.F.; Zolin, R.; Hartman, J.L. The central role of communication in developing trust and its effect on employee involvement. J. Bus. Commun. 2009, 46, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Garcia, J.A.; Conci, G. Exploratory study of high involvement work practices: Identification of the dimensions and proposal of questionnaire to measure the degree of use in the company. Intang. Cap. 2009, 5, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, M.I.; Grayson, D. Internal marketing for engaging employees on the corporate responsibility journey. Intang. Cap. 2012, 8, 275–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.P.; Bajpai, N. Teamwork a key driver in organizations and its impact on job satisfaction of employees in Indian public and private sector organizations. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2014, 15, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingraham, P.W.; Getha-Taylor, H. Leadership in the public sector: Models and assumptions for leadership development in the federal government. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2004, 24, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne Boss, R.; Dunford, B.B.; Boss, A.D.; McConkie, M.L. Sustainable change in the public sector: The longitudinal benefits of organization development. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2010, 46, 436–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshawabkeh, A.; Razmak, J.; Qasim, A.; Kharbat, F.F. Enhancing internal communication in organisations using enterprise social networking. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Res. 2018, 15, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalos, D.L.; Boehm-Kaufman, M.R. Four common misconceptions in exploratory factor analysis. In Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends: Doctrine, Verity and Fable in the Organizational and Social Sciences; Lance, C.E., Vandenberg, R.J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H.O.A. Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. In Systems under Indirect Observations: Part II; Jöreskog, K.G., Wold, H.O.A., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, S.; SmartPLS. Hamburg 2005. Available online: www.smartpls.de (accessed on 15 February 2018).

- Brunetto, Y.; Farr-Wharton, R. Using social identity theory to explain the job satisfaction of public sector employees. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2002, 15, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Schinoff, B.S.; Rogers, K.M. I identify with her “I identify with him”: Unpacking the dynamics of personal identification in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 28–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F. Two Structural Equation Models. LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modelling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Bridging Design and Behavioural Research with Variance-Based Structural Equation Modelling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuberth, F.; Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K. Confirmatory composite analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P. Fit indices in covariance structure modelling. Sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modelling in new technology research. Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Geisser, S. A predictive a roach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1974, 36, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).