Effects of Teaching Games on Decision Making and Skill Execution: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Assessment of Risk of Bias

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

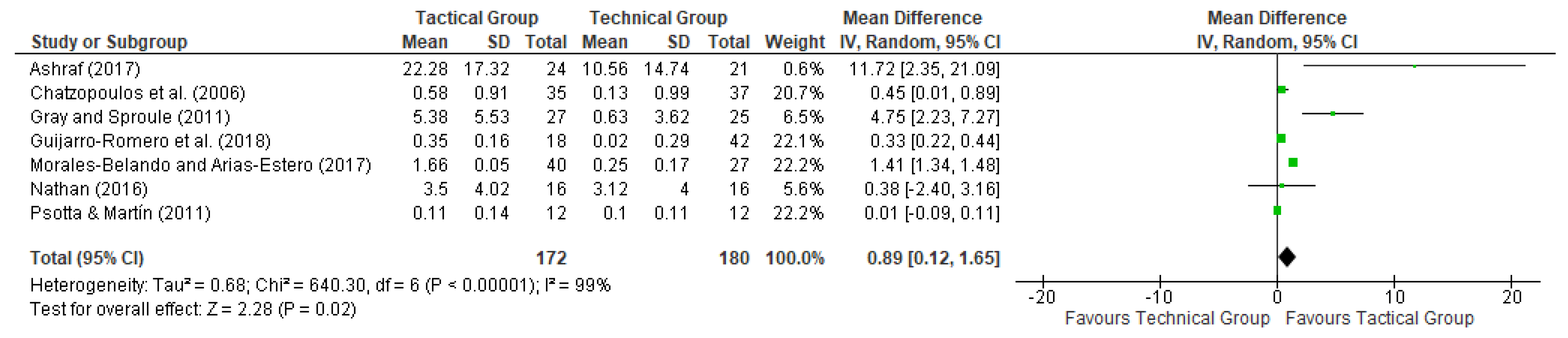

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Risk of Bias

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. Interventions

3.5. Outcome Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singleton, E. More than ‘just a game’: History, pedagogy, and games in physical education. Phys. Health Educ. J. 2010, 76, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, D.; Thorpe, R. A model for the teaching of games in the secondary school. Bull. Phys. Educ. 1982, 10, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Light, R.; Tan, S. Culture, embodied experience and teachers’ development of TGfU in Australia and Singapore. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2006, 12, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weadon, D. Drills & skills in Australian Football; Australian Football League: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blomquist, M.; Luhtanen, P.; Laakso, L. Comparison between two types of instruction in badminton. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. 2001, 6, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, A.; Valero, A.; Casey, A. What are we being told about how to teach games? A three-dimensional analysis of comparative research into different instructional studies in Physical Education and School Sports. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Ac. 2010, 6, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, B.C.; Light, R.L. A challenge to the idea of an authentic version of a Game Based Approach. In 2015 Game Sense for Teachers and Coaches Conference Proceedings; Bruce, J., North, C., Eds.; University of Canterbury College of Education, Health and Human Development: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2016; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. Game centred training and learning in Australia Rules football: Progressions and challenges. In 2015 Game Sense for Teachers and Coaches Conference Proceedings; Bruce, J., North, C., Eds.; University of Canterbury College of Education, Health and Human Development: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2016; pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pill, S. Informing Game Sense pedagogy with dynamic systems theory for coaching Volleyball. In 2015 Game Sense for Teachers and Coaches Conference Proceedings; Bruce, J., North, C., Eds.; University of Canterbury College of Education, Health and Human Development: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2016; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, J.E.; Ward, P.; Wallhead, T.L. The transfer of learning from play practices to game play in young adult soccer players. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2006, 11, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; Cushion, C.J.; Wegis, H.M.; Massa-Gonzalez, A.N. Teaching games for understanding in American high-school soccer: A quantitative data analysis using the game performance assessment instrument. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2010, 15, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D.; MacPhail, A. Teaching Games for Understanding and Situated learning: Rethinking the Bunker-Thorpe Model. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2002, 21, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, G. Systematic assessment of game-centred approach practices—the game-centred approach Assessment Scaffold. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2015, 20, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; Jarrett, K. A review of the game-centred approaches to teaching and coaching literature since 2006. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2014, 19, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A. Games Centered Approaches in Teaching Children & Adolescents: Systematic Review of Associated Student Outcomes. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2015, 14, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovegno, I.; Nevett, M.; Brock, S.; Babiarz, M. Teaching and Learning Basic Invasion-Game Tactics in 4th Grade: A Descriptive Study from Situated and Constraints Theoretical Perspectives. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2001, 20, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslin, J.; Mitchell, S. Game-Centred Approaches to Teaching Physical Education. In The Handbook of Physical Education; Kirk, D., MacDonald, D., O’Sullivan, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 627–651. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelles, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA. Int. J. Surg. 2009, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guijarro-Romero, S.; Mayorga-Vega, D.; Viciana, J. Aprendizaje táctico en deportes de invasión en la educación física: Influencia del nivel inicial de los estudiantes. Movimento 2018, 24, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, O. Effects of teaching games for understanding on tactical awareness and decision making in soccer for college students. Sci. Mov. Health 2017, 17, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Belando, M.T.; Arias-Estero, J.L. Effect of Teaching Races for Understanding in Youth Sailing on Performance, Knowledge, and Adherence. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2017, 88, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S. Badminton instructional in Malaysian schools: A comparative analysis of TGfU and SDT pedagogical models. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- French, K.E.; Werner, P.H.; Taylor, K.; Hussey, K.; Jones, J. The effects of a 6 week unit of tactical, skill, or combined tactical and skill instruction on badminton performance of ninth-grade students. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1996, 15, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, S.; Sproule, J. Developing pupils’ performance in team invasion games. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2011, 16, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Psotta, R.; Martin, A. Changes in decision making skill and skill execution in soccer performance: The intervention study. Acta Gymn. 2011, 41, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatzopoulos, D.; Drakou, A.; Kotzamanidou, M.; Tsorbatzoudis, H. Girls’ soccer performance and motivation: Games vs technique approach. Percept. Motor Skills 2006, 103, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.B.; DeShon, R.P. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordic Cochrane Centre The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program], version 5.3; Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Peacock, R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ 2005, 331, 1064–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Light, R. Coaches’ experience of Game Sense: Opportunities and challenges. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2004, 9, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.; Larkin, P.L.; Williams, A.M. What learning environments help improve decision-making? Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2017, 22, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, L.L.; Mitchell, S.A.; Oslin, J.L. Teaching Sport Concepts and Skills: A Tactical Games Approach; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, B.; Sumara, D. Why aren’t they getting this? Working through the regressive myths of constructivist pedagogy. Teach. Educ. 2003, 14, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; Cushion, C.J.; Massa-Gonzalez, A.N. Learning a new method: Teaching Games for Understanding in the coaches’ eyes. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedag. 2010, 15, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Response to Each Item Level of Evidence | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total Score |

| Guijarro-Romero et al., 2018 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Ashraf 2017 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Morales-Belando and Arias-Estero 2017 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Nathan 2016 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Gray and Sproule 2011 | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Psotta and Martin 2011 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 |

| Chatzopoulos et al., 2006 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Characteristics of the Sample | Protocol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Sample Size of Groups and Sex | Age (SD) and Education Level/Setting | Tactical Group Treatment | Technical Group Treatment |

| Guijarro-Romero et al., 2018 | Spain | TEG *: 42 (16 males and 26 females) TAGLIL ***: 23 (7 males and 16 female) In meta-analyses, it only used data from this group TAGHIL: 20 (16 males and 4 females) | 10–12 years Primary school | Tactical approach | Technical approach |

| Ashraf 2017 | Romania | TEG: 21 (NR ****) TAG **: 24 (NR) | 20 (1.2) 20 (1.9) College students | Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) | Traditional method |

| Morales-Belando and Arias-Estero 2017 | South of Europe | TEG: 27 (NR) TAG: 40 (NR) 45 males and 22 females (global data) | 9.32 (2.60) (global data) Sailing school | Teaching Races for Understanding (TRfU) | Traditional teaching mode |

| Nathan 2016 | Malaysia | TEG: 16 (8 females and 8 males) TAG: 16 (8 females and 8 males) | 15.50 (1.00) (global data) Badminton school | TGfU revised | Skill Drill Technical |

| Gray and Sproule 2011 | Scotland | TEG: 25 (12 females and 13 males) TAG: 27 (11 females and 16 males) * In meta-analyses, it used data on-the-ball “good” for decision making and data “successful” for skill execution | 12.50 (0.20) 12.50 (0.30) Secondary school | Game-based approach | Skill-focused approach |

| Psotta and Martin 2011 | Czech Republic | TEG: 12 (females) TAG: 12 (females) | 21.00 (0.70) 20.70 (0.80) College students | Technical-tactical model with an emphasis on orientation to tactical | Technical-tactical model with an emphasis on orientation to technical skills |

| Chatzopoulos et al., (2006) | Greece | TEG: 37 (females) TAG: 35 (females) | 12–13 years Middle school | Games approach | Technique approach |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abad Robles, M.T.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Fernández-Espínola, C.; Castillo Viera, E.; Giménez Fuentes-Guerra, F.J. Effects of Teaching Games on Decision Making and Skill Execution: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020505

Abad Robles MT, Collado-Mateo D, Fernández-Espínola C, Castillo Viera E, Giménez Fuentes-Guerra FJ. Effects of Teaching Games on Decision Making and Skill Execution: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(2):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020505

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbad Robles, Manuel Tomás, Daniel Collado-Mateo, Carlos Fernández-Espínola, Estefanía Castillo Viera, and Francisco Javier Giménez Fuentes-Guerra. 2020. "Effects of Teaching Games on Decision Making and Skill Execution: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 2: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020505