Self-Perceptions and Behavior of Older People Living Alone

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

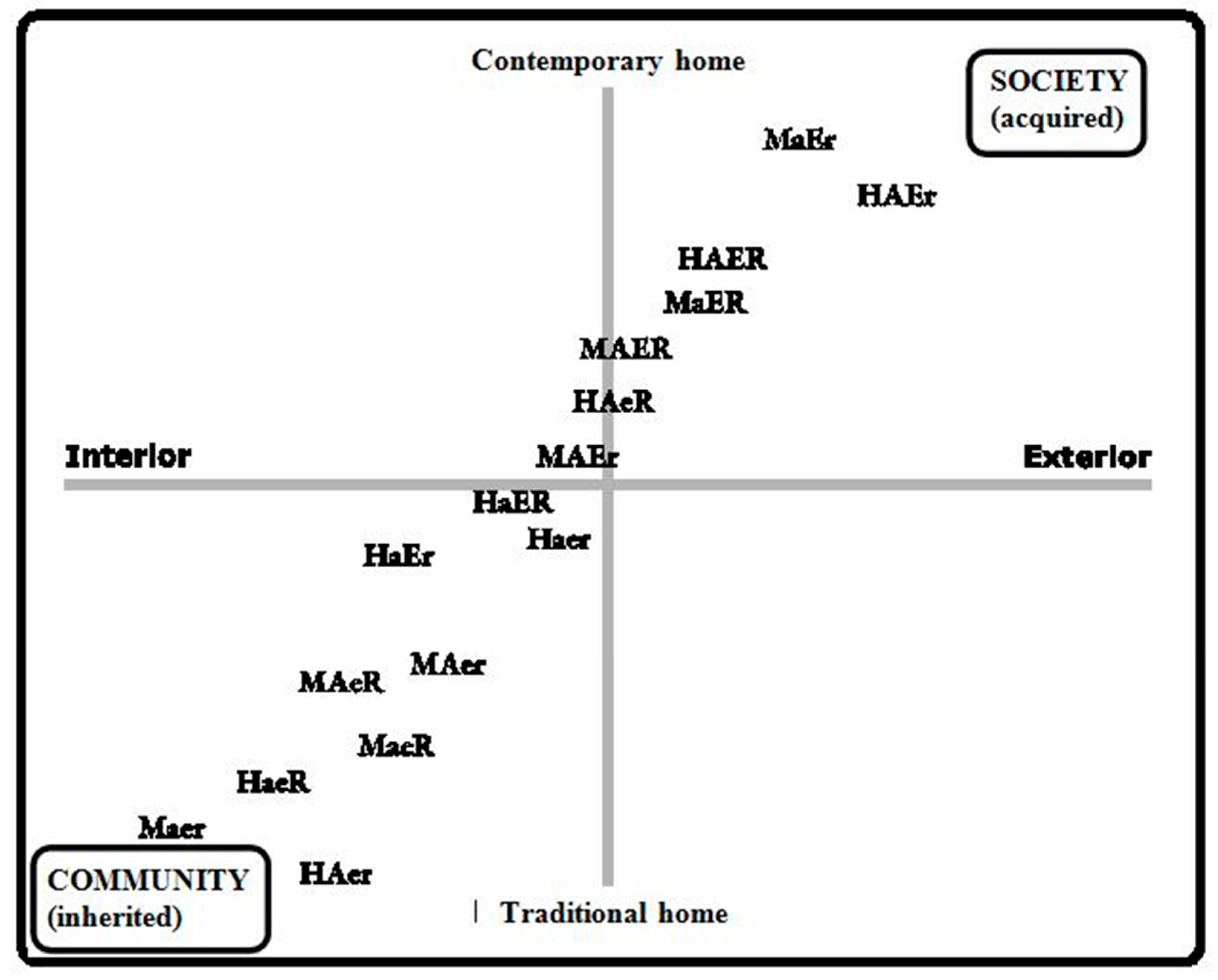

2.1. Theoretical Approach to the Concepts of the Theory of Bourdieu

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; WHO Press: Luxemburg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Díaz, J.; Abellán García, A. Envejecimiento demográfico y vejez en España. Panor. Soc. 2018, 28, 11–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Díaz, J. Feminización de la vejez y Estado del Bienestar en España. Rev. Esp. Investig. Sociol. 2003, 104, 91–121. [Google Scholar]

- Soldevilla Ágreda, J.J. La enfermería de la vejez, ayer, hoy y mañana. Enferm. Gerontol. 2009, 13, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A.; Lowenstein, A. A European perspective on quality of life in old age. Eur. J. Ageing 2009, 6, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durán Bernardino, M. La protección de las personas en situación de dependencia desde el Sistema Nacional de la Salud hacia la privatización. In Público y Privado en el Sistema de Seguridad Social; Asociación Española de Salud y Seguridad Social (Coord): Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Abellán García, A.; Ayala García, A.; Pérez Díaz, J.; Pujol Rodríguez, R. Un perfil de las personas mayores en España. Indicadores estadísticos básicos. Informes Envejecimiento en red nº 17; INSERSO: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/enred-indicadoresbasicos18.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Abellán García, A.; Esparza Catalá, C.; Pérez Díaz, J. Evolución y estructura de la población en situación de dependencia. Cuad. Relac. Labor. 2011, 29, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Encuesta de Discapacidad, Autonomía Personal y Situaciones de Dependencia (EDAD); Ministerio de Servicios Sociales: Madrid, Spain, 2019.

- Bongaarts, J.; Zimmer, Z. Living Arrangements of Older Adults in the Developing World: An Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey Household Surveys. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 57B, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salgado-de Snyder, V.N.; Wong, R. Género y pobreza: Determinantes de la salud en la vejez. Rev. Salud Pública de México 2007, 49, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neugarten, B.L. The future and the young old. Gerontologist 1975, 15, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales. Encuesta Sobre Personas Mayores; Ministerio de Servicios Sociales: Madrid, Spain, 2009.

- Zunzunegui, M.V.; Rodriguez-Laso, A.; Otero, S.M.F.; Pluijm, S.; Nikula, S.; Blumstein, T.; Jylhä, M.; Minicuci, D.J.; Deeg, D.J.H.; CLESA Working Group. Disability and social ties: Comparative findings of the CLESA study. Eur. J. Ageing 2005, 2, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verbrugge, L.M.; Jette, A.M. The disablement process. Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobar, M.A. Redes Sociales Como Factor Predictivo de Situaciones de Discapacidad al Comienzo de la Vejez. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma, Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thierry, X. Risques de mortalité et de surmortalité au cours des dix première annés de veuvege. Population 1999, 54, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L. Espacio Abierto Cuaderno Venezolano de Sociología; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Arriola, M.J.; Beloki, U. Personas que viven solas: Envejecer en el propio entorno con calidad, ¿realidad o reto? Let. Deusto 2005, 35, 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto Sancho, D.; Etxeberria Arritxabal, I.; Galdona Erquizia, N.; Urdaneta Artola, E.; Yanguas Lezaun, J. Las Dimensiones Subjetivas del Envejecimiento; Fundación INGEMA; Instituto Gerontológico Matia: San Sebastián, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; Organic Group on Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health; Department of Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases and Health Promotion Aging and Life Cycle. Envejecimiento Activo: Un Marco Político. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2002, 37, 74–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, M.A. La Medición de la capacidad funcional en el mayor desde la perspectiva de los apoyos necesarios. Geriátrika 2003, 19, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Puga, M.D.; Abellán, A. El Proceso de Discapacidad: Un Análisis de la Encuesta Sobre Discapacidades. Deficiencias y Estado de Salud; Fundación Pfizer: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carp, F. Housing and living environments of older people. In Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences; Binstock, R.H., Shanas, E., Eds.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 244–271. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, F.; González, M.; Senders, G.; Aymerich, M.; Domingo, A.; del Valle, A. Indicadores sociales y psicosociales de la calidad de vida de las personas mayores de un municipio. Interv. Psicosoc. 2001, 10, 355–378. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, J.A.; Cembranos, F. La Soledad; Aguilar: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fericgla, J.M. Envejecer. Una Antropología de la Ancianidad; HERDER: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Giró Miranda, J. Envejecimiento Activo, Envejecimiento en Positivo; Universidad de la Rioja: Logroño, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Espacio social y poder simbólico. In Cosas Dichas; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 1987; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Los tres estados del capital cultural. Sociológica 1987, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Algunas propiedades de los campos. In Sociología y Cultura; Conaculta: Mexico City, Mexico, 1990; pp. 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Capital, Cultural, Escuela y Espacio Social; Siglo XX I: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Razones Prácticas. Sobre la Teoría de la Acción; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Intelectuales, Política y Poder; Eudeba: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R. Pierre Bourdieu; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Wacquant, L. Respuestas. Por una Antropología Reflexiva; Grijalbo: Mexico City, Mexico, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. La Dominación Masculine; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, J.F. Pierre Bourdieu. A Critical Introduction; Pluto: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.C. Los Herederos: Los Estudiantes y la Cultura; Siglo Veintiuno: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo-Estrada, J.; Molina-Mula, J.; Miquel Novajra, A.; Taltavull Aparicio, J.M. Estrategias de cuidados de las familias con las personas mayores que viven solas. Index Enferm. 2013, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, A. Las Prácticas Sociales: Una Introducción a Pierre Bourdieu; Tierradenadie: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Granés, C. Pierre Bourdieu: La profecía que no se autocumple. Let. Libres 2008, 77, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, J.; Kontos, P.; Dyck, I.; McKeever, P.; Poland, B. The personal significance of home: Habitus and the experience of receiving lon-term home care. Sociol. Health Illn. 2005, 27, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel Novajra, A. El Campo en la Cabeza. Pervivencia del Agrarismo en la Construcción de la Identidad; Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Valles, M. Entrevistas Cualitativas. Cuadernos Metodológicos nº 32; The College for International Studies: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, F. Análisis Sociológico del Sistema de Discursos; The College for International Studies: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Montorio Cerrato, I.; Losada Baltar, A. Una Visión Psicosocial de la Dependencia. Desafiando la Perspectiva Tradicional 2004; Informes Portal Mayores, nº 12; Portal Mayores: Madrid, Spain, 2008; Available online: http://www.imsersomayores.csic.es/documentos/documentos/montorio-vision-01.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2008).

- Reitzes, D.C.; Mutran, E.J.; Verrill, L.A. Activities and self-esteem. Res. Aging 1995, 17, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo Higuera, J.C. La soledad en los mayores. ARS MED. Rev. Cienc. Méd. 2016, 13, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, O. Pierre Bourdieu, ¿Agente o Actor? Tóp. Humanismo 2003, 90, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Jiménez, D.; Colás-Taugís, M.I.; Padín-Minaya, C.; Ruiz-Jiménez, D.; Padín-Minaya, C.; Morell-Macaya, R. Envejecer: Aspectos positivos, capacidad funcional, percepción de salud y síndromes geriátricos en una población mayor de 70 años. Enferm. Clín. 2006, 16, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, E.; Comín, M.; Montón, G.; Martínez, T.; Magallón, R.; Garcúa-Campayo, J. Determinantes de la capacidad funcional en personas mayores según el género. Gerokomos 2013, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ducharme, F.; Corin, E.Y. A t-il restructurations des sistema es adaptatives suite au veuvage? Une étude longitudinales. Can. J. Aging 2000, 19, 160–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelantado, F.; Graíño, C.S.; de Andrés Pizarro, J.; Feliu, T.; de Vaca, P.M.N.-C. Los mayores de 85 años en Sabadell. Rev. Multidiscip. Gerontol. 2004, 14, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Ancizu, I.; Bazo, M.T. The care-giving dimension. In Ageing Intergenerational Relations, Care Systems and Quality of Life: An Introduction to the OASIS Project; Daatland, S.O., Herlofson, K., Eds.; Norwegian Social Research: Oslo, Norway, 2001; pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Compán Vázquez, D.; Sánchez González, D. Los ancianos al desván. El proceso de degradación biológica y social de la población mayor en el municipio de Granada. Cuad. Geogr. 2005, 36, 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- López Doblas, J.; Díaz Conde, M.P. El sentimiento de soledad en la vejez. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2018, 76, e085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Villarreal, D.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, A.M.; Ramírez-Llarás, A.; García-Uso, A.; Fabregat Casamitiana, M.A.; Fusté Vendrell, A. Necesidades percibidas por mujeres mayores que viven solas y reciben atención domiciliaria: Investigación cualitativa. Enferm. Clín. 2007, 17, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Calvo, E. El Poder Gris. Una Nueva Forma de Entender la Vejez; Random House Mondadori: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Ortiz, L. Envejecer en Femenino. Las Mujeres Mayores en España a Comienzos del Siglo XXI; IMSERSO Instituto de la Mujer: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro Ruiz, V.; Gil López, A. La calidad de las viviendas de los ancianos y sus preferencias ante la institucionalización. Intervención Psicosocial 2005, 14, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo-Rubio, A.; Martínez-Silva, P. Agentes y campos sociales en la seguridad del paciente de tres hospitales de Bogotá, Colombia. Rev. Gerenc. Políticas Salud 2010, 9, 150–178. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, M.; Miller, D.A. La Práctica Clínica del Trabajo Social con las Personas Mayors; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bazo, M.T.; Ancizu, I. El papel de la familia y los servicios en el mantenimiento de la autonomía de las personas mayores: Una perspectiva internacional comparada. Rev. Esp. Investig. Sociol. 2004, 105, 43–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Category “A Desire to Stay at Home” | ||

|---|---|---|

| CODE | DEFINITION | VERBATIM |

| The home as a place of freedom and power | The home is important because it is the place where they have lived, where they conserve the most freedom to do what they want. At home, they do not have to give explanations or be forced to take orders. | E 13: I like being alone a lot and doing whatever I want. E 16: When you close the door (…), everything is shut out. You’re inside and you’re the boss, the one who rules the roost there. |

| The home as a form of identity | The presence of two attitudes to the home: one traditional view, where it is seen as a person’s own inherited home to be passed on to subsequent generations, with an affective significance for the family alone. Tasks are not delegated when it comes to caring for the home. With the other more up-to-date approach to the home, older people see it as a comfortable physical space with social connotations, where they can enjoy their memories. It is an open place for coming and going, with lots of modern touches. When it comes to domestic tasks, hired help is preferred. | E 16: The day I get a place in an old people’s home, I’ll use it, but purely as a residential base (…). Yes, to live and, logically for food too, but the rest… E 7: The home is very important. It is a great refuge, filled with memories, brimming with things evocative of the past. |

| Concern about the future in terms of the type of homelife | They tend to live for today, particularly those who are older, rather than contemplating their future non-existence. They are aware that, to a greater or lesser extent, tomorrow will bring disabilities and they tend to live in the present. Their perception of the future changes the value that is placed on time. | E 7: Living alone will become increasingly complicated (…). I don’t even want to contemplate it. Needless to say, one day, if I get worse, I’ll have to think about doing what many older people do, finding somewhere. E 14: Everyone my age is dead (…) I saw one in a wheelchair the other day (…). You have to live for today. You don’t think about tomorrow because it’ll make life a misery. |

| Living alone as a way of life | They avoid thinking about the possible drawbacks of living alone (even though it is a worry for all of them). Living alone is seen as an imposed situation which happened unexpectedly and which they accept with an effort. In such cases, there is a greater concern about the availability of social and family support networks. Being alone is also perceived as a way of life, with positive connotations in terms of freedom, to the extent that they prefer not to live with a companion or even with the family. Possible problems that might emerge when living alone worry them, rather than actually being on their own. | E 14: When I ended up on my own, I wanted to kill myself, I wanted to kill myself, kill myself (…) I aged, I didn’t go out (…) and, when it’s 6 o’clock in the morning and the sun rises, this bird is already singing and calling me (…) animals keep you company. E 11: I’d feel very uncomfortable if I was accompanied all day (…) a person’s presence, now my daughter’s coming and I’m very pleased (…) but, understand me, it’d complicate my life a lot if she came to live here. |

| Differences according to gender | The recognition by the generation in question that gender makes a big difference in the activities carried out in the home when one lives alone. Men and women adopt different stances and strategies (women as gatherers and men as hunters). For men, living alone is harder when it comes to everyday tasks in the home. | E 13: A huge number of widowers have never even touched a dish in their lives (…) a man is not trained to do domestic tasks like a woman. E 14: If the woman is missing, it all goes to pot, but if the man is missing, the home is like this (…) she instinctively cares for the home. I do it because I have to. |

| The relationship between perceived perceptions of independence and over-estimating abilities | Being independent and—for them, what is synonymous with this—being able to live alone are seen by more traditional Older people as not needing assistance with hygiene or meals. They tend to show off their abilities and to over-estimate them, while also hiding their losses. They consider them to be inherent in a person and associated with survival and keeping up the fight. If they can get by, they prefer not to ask for help or to hire help. They tend to accept situations and are dilatory when it comes to making changes. For other older people, their abilities are associated with intellectual skills, built up as a result of their training, work, life experiences and discipline. Adapting to change is part of being successful at aging. If they have aid or assistance at their disposal, they use it. | E 13: I’ve always been like this, very independent and self-reliant. I don’t like to rely on anyone. I never carry even a parcel, I can’t carry any weight, my bag’s too much for me (…) everyone gets old, but you have to get there in an intelligent way; that is, without demands. E 16: Moral strength helps you to tackle any situation, together with discipline (…) I have conserved some not over-strict religious principles (…). It’s a base, a platform, an aid; that is, something to grab on to. |

| Category “Changes and Everyday Aspects of Domestic Life” | ||

| CODE | DEFINITION | VERBATIM |

| Strategies to stay in the home | Older people, especially the oldest, have an attitude of living today in the face of the non-existence of a future. Attitude, which is necessary in order not to anticipate losses and avoid planning for the future. Older people, aware that to a greater or lesser extent tomorrow will bring disability and illness, tend to live in the present. Their perception of the future modifies the value of time, there is no rush, the rhythm in old age is slower than that of an adult. After this stage there is no other. In known spaces, risks are minimized and points that require special attention are identified; In the house in which they have lived, the older person has a sense of security and control, regardless of architectural barriers. Older people show a tendency to reduce the demands on home maintenance and activities of daily living, as a way of compensating for changes in old age. The adaptation of the home is decisive in the way in which the older person seems to resolve the difficulties in daily life to satisfy basic needs. | E 13: Student furniture, the cheapest I could find, and I set up a student-type flat that’s easy to clean (…). I looked for all the comforts, a lift, parquet, hot water and no dangers. E 3: Now I have a gadget for opening cans, like tins of tomatoes (…) often I don’t look at the expiry date (…) that box for the meter was put in, and my son-in-law took charge of doing it, and now they’ve brought me some papers that I had to sign that I told my granddaughter about… |

| Self-care as a way of continuing to live on one’s own | Caring for oneself in necessary matters related to eating properly, taking prescribed medicine and doing physical activity. More traditional older people prefer to eat what they cook. They identify the beneficial properties of different produce and account for their reason for eating this type of food. They prefer not to have to cook. Physical activity/healthy leisure activities for more traditional older people mean taking a walk. More up-to-date older people do different types of physical activity (swimming, gym, cycling) as well as travelling. They also attend musical activities. They are interested in languages, discussion activities, or classes. | E 16: I try and eat a good diet, with lots of vegetables (…) I try to be fairly prudent, it’s a bit like being an epicurean (…). Recipes, yes. Well, it’s here, written down on the page or if not, if it’s more complicated, I type it on the computer. E 2: I go to activities for the third age and to gym and memory training (…) that way, you’ve got a reason to say I’VE GOT to get up. |

| Category “Reliance on Social and Family Assistance” | ||

| CODE | DEFINITION | VERBATIM |

| Traditional family: care is a moral duty | More traditional older people who live alone consider the family to be by far the main support. Physical proximity is important. If this support is absent or not available, certain neighbors rank next in the support network. Older people with a traditional notion of the family believe that relatives have a moral obligation to care for them. They do not contemplate the possibility of hiring external carers or help in domestic tasks. | E 2: Having family, so that you can live alone, is better, but not essential. E 8: Because nowadays children or daughters-in-law all work, you see, and they can’t look after you (…) because my daughters-in-law, one works until 7 p.m. since she’s seen the lie of the land and she’ll not get involved, and the other has what you might call a servant, so no way will she get involved helping out here! (...). If I go to the café—I’ve got friends there—if anything happens, they know they’ve got to help me. |

| Alternatives to traditional care | Those with a more up-to-date approach to the family take a broader view to their support network, including friends, neighbors, unmarried partners and others. They believe that they can count on the support of a social and family network and hired services to meet their care needs. These older people do not believe that care is a family obligation. | E 13: The neighbors keep an eye out. If they see the curtains are closed, they might come up and see if I’m ill (…) if my friends from the bars don’t see me—I spend half my life down there -, they ask about me. E 17: I’m very lucky. A lot of mothers or fathers haven’t much luck with their children (...). But my daughter says “You’ll NEVER, never go to another house. When you can’t think for yourself, you’ll come with me”. |

| Category “The Use of Social Services and Resources” | ||

| CODE | DEFINITION | VERBATIM |

| Perceptions of healthcare professionals | They regard attention by healthcare professionals as occasional and basically see them as the suppliers of medicines. They cannot identify the managing body that provides the relevant care and do not make a request for assistance. Relatives tend to act as a middleman in relations with healthcare professionals so that the older person does not have to travel to the health center so much. | E 13: He writes the prescriptions but he never asks about me (…) No one’s come here, no one’s lent me a hand (…) I had to go twice to get the medicine. E 11: They just sign the prescriptions and, from time to time, the knee sometimes. I take my blood pressure and the nurse too, we usually coincide (…) but no, they haven’t taken records of my medical history or anything remotely like that. |

| Technology and tools to provide support for people | Older people often act in a dependent way to show that they are dependent. Although they are aware of support systems that could improve their everyday lives, they do not feel capable of carrying out the complex formalities needed to request this assistance. When relatives are younger and available, they tend to take charge of most of the formalities needed to apply for help. The older people are unaware of the existence or availability of some support tools or systems and they are misled in knowing how suitable or not they would be. Call alert telecare is the best-known, most widely used tool, but the older people have different attitudes to it. Some consider it to be a convenient, easy-to-use device that guarantees greater security and others believe that it is not so convenient and that it mainly sets the family’s mind at ease. | [Call alert telecare] I haven’t asked for anything because I don’t want to pay. What they offer isn’t worth it. I’ll use my mobile to ring if I’m ill or feeling bad. E 1: I asked for...I don’t know…whatever they would give me in May two years ago (…) “he can cope, he’s okay, he’s okay” (...). [Home help] The same home help that comes here goes to nine houses and finishes at 3 a.m. |

| Alternatives to their own home | When the older person cannot go on living in their own home alone, they consider two possible alternatives: to live in an old people’s home, overcoming any negative connotations that these homes may have for people in general and for them, or going to live with a relative, generally their children. In this last case, whether there is enough room there or not can determine whether they have to take turns at living in two different carers’ houses. Whether the family has enough time or not to accompany the older person can determine the need for outside help. | E 13: An attempt at living at a son’s house that ended in disaster, that simply wasn’t possible (…) of course, you have to remember that the home isn’t yours and so it’s very difficult. E 9: Sometimes you’ve got to go to an old people’s home because there are things you need (…) for my age, my illness, my sugar level (…) but while it’s still not urgent or necessary, I’m not going! |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina-Mula, J.; Gallo-Estrada, J.; González-Trujillo, A. Self-Perceptions and Behavior of Older People Living Alone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238739

Molina-Mula J, Gallo-Estrada J, González-Trujillo A. Self-Perceptions and Behavior of Older People Living Alone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238739

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina-Mula, Jesús, Julia Gallo-Estrada, and Antonio González-Trujillo. 2020. "Self-Perceptions and Behavior of Older People Living Alone" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238739