Measuring Residents’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility at Small- and Medium-Sized Sports Events

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Stakeholders Theory in Sporting Events

2.2. CSR in Sporting Events

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Sample

3.2. Measures

4. Results

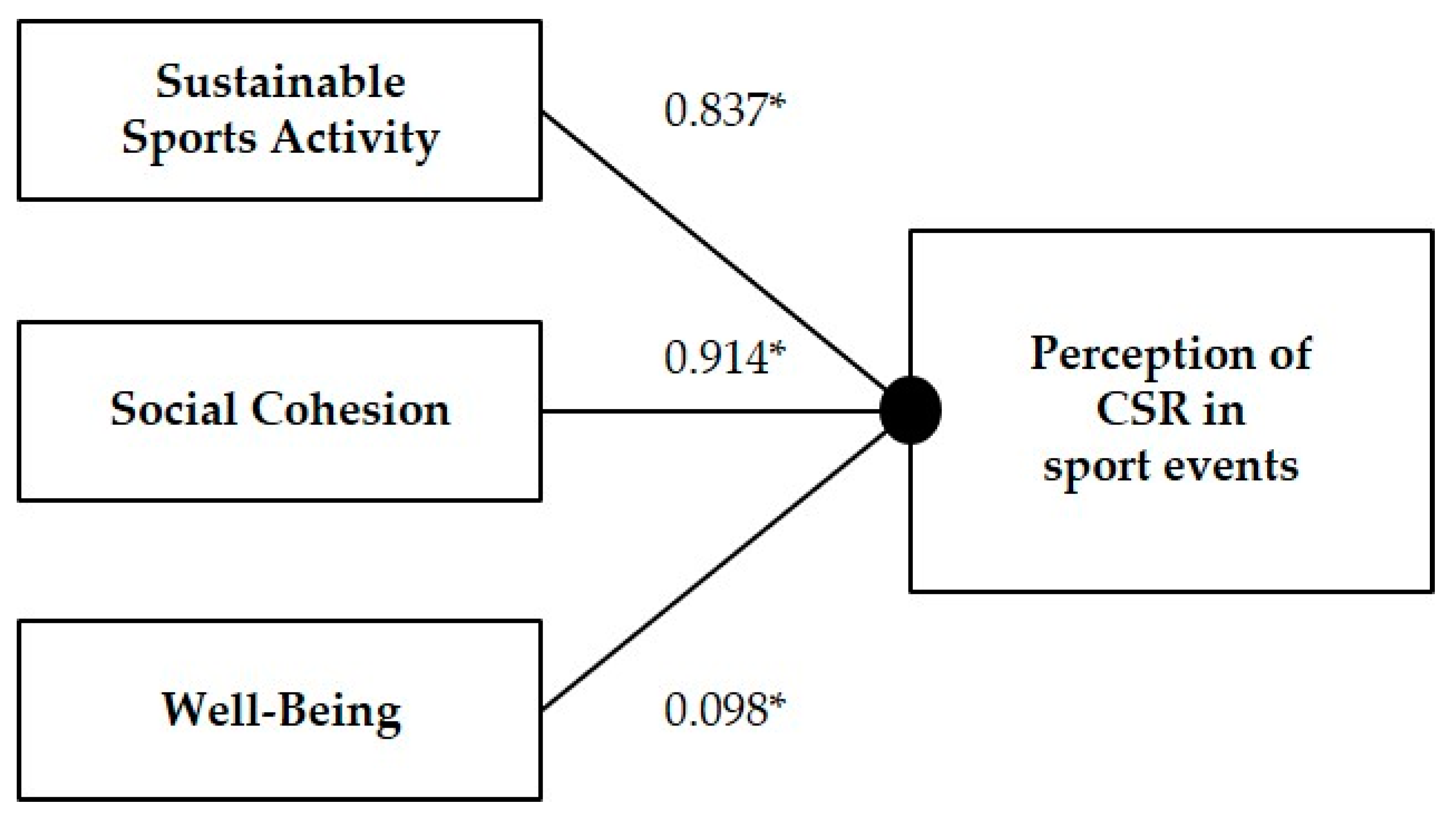

Measurement Quality and Relationship between Variables

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The present research contributes methodologically by offering a valid and reliable multidimensional scale of measurement for the perception of CSR in sports events from the perspectives of residents on 33 items composed of three dimensions: “Sustainable Sports Activity” (16 items), “Social Cohesion” (11 items), and “Well-being” (6 items).

- These dimensions resulting from the CFA combine the indicators necessary to determine the residents’ perceptions of CSR implemented in a sports event. Actions linked to “Sustainable Sports Activity”, such as sports for all, the encouragement of physical activity, the promotion of good sports practices in the natural environment, cultural exchange, tourist development, etc.; “Social Cohesion”, such as promoting the value and conservation of historical and cultural heritage, the encouragement and development of local trade, investments in sports, the promotion of cultural activities, etc.; and “Well-being”, such as minimizing negative impacts, such as pollution, traffic congestion or roadblocks, entertainment, environmental conservation, etc., could, if integrated into the planning and organization of the event, make the event socially responsible.

- The final objective of this scale is to determine the perception of local residents on the CSR actions implemented in a small–medium scale sports event. It is important to highlight the difficulty of not having reference studies, so these results are the foundation for continuing this line of research.

6.1. Managerial Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | |

|---|---|

| 1 | “La Ruta de las Fortalezas” promotes sports among youth. |

| 2 | It promotes the participation of women in sports. |

| 3 | It promotes sports participation in adulthood (30–40 years of age). |

| 4 | It promotes and increases knowledge about local sports clubs. |

| 5 | Interest in mountain running/athletics/physical activity is increasing among residents. |

| 6 | It increases my knowledge about the organization of this type of race. |

| 7 | It helps one positively consider the environmental protection of the territory. |

| 8 | “La Ruta de las Fortalezas” respects the conservation of natural resources. |

| 9 | It serves as a stimulus for the recovery and maintenance of historic roads and trails. |

| 10 | It contributes to improving the hospitality and solidarity of the city with the assistants and participants of the event. |

| 11 | I feel like I own the event. |

| 12 | It provides an opportunity to meet new people. |

| 13 | Celebrating this event in my city helps me feel good about myself and society as a whole. |

| 14 | This event improves my quality of life. |

| 15 | It attracts tourists to Cartagena. |

| 16 | “La Ruta de las Fortalezas” increases my pride as an inhabitant of Cartagena. |

| 17 | Through the event, the cultural heritage of the town is valued. |

| 18 | “La Ruta de las Fortalezas” serves as a stimulus for the preservation of local culture. |

| 19 | It provides an incentive for the restoration and maintenance of historic buildings. |

| 20 | It increases the knowledge of the cultural and historical heritage of the town. |

| 21 | The celebration of “La Ruta de las Fortalezas” encourages the promotion of local traditions. |

| 22 | It provides an opportunity for local business. |

| 23 | It helps generate opportunities for employment. |

| 24 | The celebration of “La Ruta de las Fortalezas” contributes to increasing the investments of the City Council in sports. |

| 25 | The educational activities (Congresses, etc.) of “La Ruta de las Fortalezas” culturally enrich the population of Cartagena. |

| 26 | It promotes the inclusion of groups under risk of social exclusion. |

| 27 | It promotes volunteering for the celebration of other events in Cartagena. |

| 28 | It makes it difficult for residents to access public spaces, streets, or roads. |

| 29 | It causes an increase in the prices of some products, such as food and/or services, in the locality. |

| 30 | It causes alterations in the population’s daily life (e.g., noises, traffic jams). |

| 31 | It causes the agglomeration and/or disorderly accumulation of people in the city. |

| 32 | This event causes noise pollution. |

| 33 | During its course, the event causes the deterioration of the environment (e.g., pollution, rubbish, erosion, etc.). |

References

- Zhou, J.; Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions towards the impacts of the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L. The evolution of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Kaplanidou, K. Legacy perceptions among host Tour de Taiwan residents: The mediating effect of quality of life. Leis. Stud. 2016, 36, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; González, R.J.; Añó, V.; Ayora, D. Percepción de los visitantes sobre el impacto social y sus intenciones con respecto a la celebración de un evento deportivo de pequeña escala. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2016, 25, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Mercado, H. Environmentally responsible value orientations: Perspectives from public assembly facility managers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Mason, D.S. The changing stakeholder map of Formula One Grand Prix in Shanghai. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, M.M. Evolution and issue patterns for major-sport-event organizing committees and their stakeholders. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 135–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.M.; Séguin, B. Factors that led to the drowning of a World Championship Organizing Committee: A stakeholder approach. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2007, 7, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S. Event stakeholder management: Developing sustainable rural event practices. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2011, 2, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentini, A.; Pianese, T. The relationships among stakeholders in the organization of men’s professional tennis events. Glob. Bus. Manag. R. Int. J. 2011, 3, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.A.; Forster, W.R. CSR and stakeholder theory: A tale of Adam Smith. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.J.; Tewari, M. Firm characteristics, industry context, and investor reactions to environmental CSR: A stakeholder theory approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzel, S.; Robertson, J.; Anagnostopoulos, C. Corporate social responsibility in professional team sports organizations: An integrative review. J. Sport Manag. 2018, 32, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Wolfe, R. More than just a game? Corporate social responsibility and Super Bowl XL. Sport Mark. Q. 2006, 15, 214–222. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Wilson, R.; Plumley, D.; Chen, X. Perceived corporate social responsibility performance in professional football and its impact on fan-based patronage intentions: An example from Chinese football. Int. J. Sport Mark. Spons. 2019, 20, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Branco, M.C.; Ribeiro, J.A. The corporatisation of football and CSR reporting by professional football clubs in Europe. Int. J. Sport Mark. Spons. 2019, 20, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K. The role and relevance of corporate social responsibility in sport: A view from the top. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, M.; Mason, D.S.; Misener, L. Social responsibility and the competitive bid process for major sporting events. J. Sport. Soc. Issues 2011, 35, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, H.; Babiak, K. Beyond the game: Perceptions and practices of corporate social responsibility in the professional sport industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Heere, B.; Parent, M.M.; Drane, D. Social responsibility and the Olympic Games: The mediating role of consumer attributions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Parent, M.M. Toward an integrated framework of corporate social responsibility, responsiveness, and citizenship in sport. Sport Manag. Rev. 2009, 13, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, N.; Taks, M. A theoretical comparison of the economic impact of large and small events. Int. J. Sport Financ. 2015, 10, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Estimating the economic impacts of a small-scale sport tourism event: The case of the Italo-Swiss mountain trail CollonTrek. Sustainability 2017, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredline, E. Host and guest relations and sport tourism. Sport Soc. 2005, 8, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J.; Kaplanidou, K.; Kang, S.J. Small-scale event sport tourism: A case study sustainable tourism. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J.; Willming, C.; Holdnak, A. Small-scale event sport tourism: Fans as tourists. Tour. Manag 2003, 24, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautbois, C.; Djaballah, M.; Desbordes, M. The social impact of participative sporting events: A cluster analysis of marathon participants based on perceived benefits. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Heffernan, C.; Yamaguchi, T.; Filo, K. Social and charitable impacts of a charity-affiliated sport event: A mixed methods study. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ko, J.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, H.J. The role of involvement and identification on event quality perceptions and satisfaction: A case of US Taekwondo Open. Asia Pac. J. Market. Logist. 2010, 22, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D. Points of leverage: Maximizing host community benefit from a regional surfing festival. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2007, 7, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S. Identifying social consequences of rural events. Event Manag. 2007, 11, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Sáez, J.A.; Segado-Segado, F.; Vidal, A. Sports events socially responsible as the engine for local development. J. Sports Econ. Manag. 2018, 8, 172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Taks, M.; Green, B.; Misener, L.; Chalip, L. Evaluating sport development outcomes: The case of a medium-sized international sport event. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taks, M.; Kesenne, S.; Chalip, L.; Green, B.C.; Martyn, S. Economic impact analysis versus cost benefit analysis: The case of a medium-sized sport event. Int. J. Sport Financ. 2011, 6, 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Gratton, C.; Dobson, N.; Shibli, S. The economic importance of major sports events: A case-study of six events. Manag. Leis. 2000, 5, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Wagner, M. The effect of family ownership on different dimensions of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from large US firms. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2014, 23, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Murphy, P.E.; Gruber, V. Consumers perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Bus. Ethics Q. 2003, 13, 503–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, L.; Musso, D.; Barreau, G.; Collas, L.B.; Addadl, A. Organising a Major Sport Event, Managing Olympic Sport Organisations; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 279–344. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R. The economic impact of local sport events: Significant, limited or otherwise? A case study or four swimming events. Manag. Leis. 2006, 11, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Kaplanidou, K.; Gibson, H.; Thapa, B.; Geldenhuys, S.; Coetzee, W. “Win in Africa, With Africa”: Social responsibility, event image, and destination benefits. The case of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Sáez, J.A. Los eventos deportivos como instrumento de desarrollo local. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2019, 14, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.; de Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Babiak, K.; Wolfe, R. Determinants of corporate social responsibility in professional sport: Internal and external factors. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 717–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, D.A.; Coughlan, R. Stakeholder relationship bonds. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.M.; Barbanti, V.J.; Chelladurai, P. Support of local residents for the 2016 Olympic Games. Event Manag. 2017, 21, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misener, L.; Mason, D.S. Fostering community development through sporting events strategies: An examination of urban regime perceptions. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 770–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Nyanjom, J. Local stakeholders, role and tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P. Corporate social responsibility in sport: An overview and keys issues. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradish, C.; Cronin, J.J. Corporate social responsibility in sport. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Cebador, M.; Rubio-Romero, J.C.; Pinto-Contreiras, J.; Gemar, G. A model to measure sustainable development in the hotel industry: A comparative study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quazi, A.M. Identifying the determinants of corporate managers’ perceived social obligations. Manag. Decis. 2003, 41, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.L.; Huang, H. Social impact of Formula One Chinese Grand Prix: A comparison of local residents’ perceptions based on the intrinsic dimension. Sport Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, M.; Đurkin, J.; Wise, N. Leveraging small-scale sport events: Challenges of organising, delivering and managing sustainable outcomes in rural communities, the case of Gorski Kotar, Croatia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poczta, J.; Dąbrowska, A.; Kazimierczak, M.; Gravelle, F.; Malchrowicz-Mośko, E. Overtourism and Medium Scale Sporting Events Organisations—The Perception of Negative Externalities by Host Residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preuss, H.; Solberg, H. Attracting major sporting events: The role of local residents. Eur. Sports Manag. Q. 2006, 6, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bek, D.; Merendino, A.; Swart, K.; Timms, J. Creating an enduring developmental legacy from FIFA2010: The Football Foundation of South Africa (FFSA). Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2018, 19, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, A. CSR in sport sponsorship consumers’ perceptions of a sponsoring brand’s CSR. Int. J. Sport Mark. Spons. 2020, 21, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currás-Pérez, R.; Dolz-Dolz, C.; Miquel-Romero, M.; Sánchez-García, I. How social, environmental, and economic CSR affects consumer-perceived value: Does perceived consumer effectiveness make a difference? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaballah, M.; Hautbois, C.; Desbordes, M. Sponsors’ CSR strategies in sport: A sensemaking approach of corporations established in France. Sport Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levermore, R. CSR for development through sport: Examining its potential and limitations. Third World Q. 2010, 31, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taek, S.; Sil, J. Host population perceptions of the impact of megaevents. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 11, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, I.; Aldaz, M. The social reputation of European companies: Does anti-corruption disclosure affect stakeholders’ perceptions? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Poczta, J. A small-scale event and a big impact—Is this relationship possible in the world of sport? The meaning of heritage sporting events for sustainable development of tourism—experiences from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aaker, D.A.; Day, G.S. Investigación de Mercados; McGraw-Hill: México City, Mexico, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. Fundamentos de la Investigación Social; International Thomson Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A. Investigación de Mercados; International Thomson Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.R.; Nelson, J.K. Métodos de Investigación en Actividad Física; Editorial Paidotribo: Badalona, Spaña, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calabuig, F.; Mundina, J.; Crespo, J. Eventqual: Una medida de la calidad percibida por los espectadores de eventos deportivos. Retos 2010, 18, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero-Dios, H.; Pérez, C. Normas para el desarrollo y revisión de estudios instrumentales. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2005, 5, 521–551. [Google Scholar]

- Wiersma, L. Conceptualization and development of the sources of enjoyment in youth sport questionnaire. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2001, 5, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Wu, E.J. EQS 6.1 for Windows; Multivariate Software Inc.: Encino, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abenza, L.; Olmedilla, A.; Ortega, E.; Esparza, F. Construcción de un registro de conductas de adherencia a la rehabilitación de lesiones deportivas. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2011, 20, 455–476. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger, S.M.; Housner, L.D. Modified Delphi investigation of exercise science in physical education teacher education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2007, 26, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, S.N.; Richard, D.C.S.; Kubany, E.S. Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal, E.; Gómez, M.J. La gestión de la calidad en las entidades deportivas. In Actes del 4º Congrés de les Ciències de l’Esport, l’Educació Física i la Recreació; Institut Nacional d′Educació Física de Catalunya, Departament de la Presidència: Lleida, Spain, 1999; pp. 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Kendall, K.W. Hosting mega events. Modelling locals’ support. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Gursoy, D.; Lee, S.-B. The impact of the 2002 World Cup on South Korea: Comparisons of pre- and post-games. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Social impact of major sports events perceived by host community. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2016, 17, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorde, T.; Greenidge, D.; Devonish, D. Local residents’ perceptions of the impacts of the ICC Cricket World Cup 2007 on Barbados: Comparisons of pre- and post-games. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudman, S. Applied Sampling; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Blumrodt, J.; Bryson, D.; Flanagan, J. European football teams’ CSR engagement impacts on customer-based brand equity. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumrodt, J.; Desbordes, M.; Bodin, D. Professional football clubs and corporate social responsibility. Sports. Bus. Manag. 2013, 3, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calabuig, F.; Parra, D.; Añó, V.; Ayora, D. Análisis de la percepción de los residentes sobre el impacto cultural y deportivo de un Gran Premio de Fórmula 1. Movimento 2014, 20, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ma, S.; Wu, J.; Rotherham, I.D. Host residents’ perception changes on major sport events. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2013, 13, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Rotherham, I.D. Residents’ changed perceptions of sport event impacts: The case of the 2012 Tour de Taiwan. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 616–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taks, M. Social sustainability of non-mega sport events in a global world. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2013, 10, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vetitnev, A.M.; Bobina, N. Residents’ perceptions of the 2014 Sochi Olympic Games. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Walker, M. Measuring the social impacts associated with Super Bowl XLIII: Preliminary development of a psychic income scale. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-W.; Lu, H.-F. Valuing residents’ perceptions of sport tourism development in Taiwan’s North Coast and Guanyinshan National Scenic Area. Asian Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 398–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Multitrait-muitimethod matrices in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Bigné, E.; Aldas-Manzano, J.; Curras-Pérez, R. A Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility Following the Sustainable Development Paradigm. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jun, H.M.; Walker, M.; Drane, D. Evaluating the perceived social impacts of hosting large-scale sport tourism events: Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kim, S. The influence of cultural aspects on public perception of the importance of CSR activity and purchase intention in Korea. Asian J. Commun. 2013, 23, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Measuring CSR image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 11, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Juslin, H. Values and corporate social responsibility perceptions of Chinese university students. J. Acad. Ethics 2012, 10, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balduck, A.-L.; Maes, M.; Buelens, M. The social impact of the Tour de France: Comparisons of residents’ pre- and post-event perceptions. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaballah, M.; Hautbois, C.; Desbordes, M. Non-mega sporting events’ social impacts: A sense making approach of local governments’ perceptions and strategies. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, M.E.; Lorenzo-Seva, U. Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychol. Methods 2011, 6, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Alders, T. London residents support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Y. Resident perceptions toward the impacts of the Macao Grand Prix. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2010, 11, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misener, L.; Mason, D.S. Towards a community centered approach to corporate community involvement in the sporting events agenda. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.B.; Kent, A. Do fans care? Assessing the influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer attitudes in the sport industry. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 743–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Athanasopoulou, P.; Douvis, J.; Kyriakis, V. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in sports: Antecedents and consequences. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2011, 1, 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Sonmez, M. Intangible balls. Bus. Strat. Rev. 2005, 16, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Westerbeek, H. Sport as a vehicle for deploying corporate social responsibility. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2007, 25, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanWynsberghe, R.; Derom, I.; Maurer, E. Social leveraging of the 2010 Olympic Games: ‘Sustainability’ in a City of Vancouver initiative. J. Pol. Res. Tour. Leis. Event 2012, 4, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misener, L. Mega-Events and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Stakeholder Perspective of Compatibility. In Proceedings of the North American Society for Sport Management Conference (NASSM), Toronto, ON, Canada, 31 May 2008; Available online: https://www.nassm.com/files/conf_abstracts/2008-325.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Dowling, M.; Robinson, L.; Washington, M. Taking advantage of the London 2012 Olympic Games: Corporate social responsibility through sport partnerships. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2013, 13, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I. Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 30, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzanella, F.; Peters, M.; Schnitzer, M. The perceptions of stakeholders in small-scale sporting events. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2019, 20, 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Sáez, J.A.; Segado Segado, F.; Calabuig-Moreno, F.; Gallardo Guerrero, A.M. Measuring Residents’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility at Small- and Medium-Sized Sports Events. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8798. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238798

Sánchez-Sáez JA, Segado Segado F, Calabuig-Moreno F, Gallardo Guerrero AM. Measuring Residents’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility at Small- and Medium-Sized Sports Events. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(23):8798. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238798

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Sáez, Juan Antonio, Francisco Segado Segado, Ferran Calabuig-Moreno, and Ana Mª Gallardo Guerrero. 2020. "Measuring Residents’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility at Small- and Medium-Sized Sports Events" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 23: 8798. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238798