Abstract

Attachment security priming has been extensively used in relationship research to explore the contents of mental models of attachment and examine the benefits derived from enhancing security. This systematic review explores the effectiveness of attachment security priming in improving positive affect and reducing negative affect in adults and children. The review searched four electronic databases for peer-reviewed journal articles. Thirty empirical studies met our inclusion criteria, including 28 adult and 2 child and adolescent samples. The findings show that attachment security priming improved positive affect and reduced negative affect relative to control primes. Supraliminal and subliminal primes were equally effective in enhancing security in one-shot prime studies (we only reviewed repeated priming studies using supraliminal primes so could not compare prime types in these). Global attachment style moderated the primed style in approximately half of the studies. Importantly, repeated priming studies showed a cumulative positive effect of security priming over time. We conclude that repeated priming study designs may be the most effective. More research is needed that explores the use of attachment security priming as a possible intervention to improve emotional wellbeing, in particular for adolescents and children.

Keywords:

attachment; security; security priming; depression; anxiety; positive affect; negative affect 1. Introduction

This systematic review evaluates the results and quality of studies using attachment security priming to reduce negative affect and/or improve positive affect in adults and children. Attachment styles represent individuals’ internalised histories of received care [1]. Experiences of care or rejection are abstracted to form trait-like mental models that drive style-congruent thinking, feeling, and behaviour [2,3]. Attachment styles are conceptualised along two dimensions: anxiety regarding abandonment and avoidance of intimacy [4]. Individuals can be low or high on either. Being high on either dimension is referred to in shorthand as being attachment ‘insecure’. Attachment styles are important predictors of the way individuals regulate affect. Individuals learn through relationships how and when to attend to their own stress and distress [5]. Each attachment dimension is associated with distinct affect regulation strategies [6,7], with insecure individuals experiencing lower positive affect and greater levels of negative affect relative to secures [8,9].

Individuals who are high in attachment anxiety find it hard to regulate their emotions. They use hyperactivation emotion regulation strategies, that is, they are hypervigilant for signs of rejection and have relationships characterised by emotional turbulence. Individuals high in attachment avoidance use deactivating emotion regulation strategies, that is, they ignore or deny emotional threats and tend toward compulsive self-reliance. By contrast, secure individuals (low on both dimensions) show optimal emotional regulation. While security of attachment has a number of positive wellbeing-related correlates and can be thought of as a protective factor against ill mental health, insecurity acts as a vulnerability factor for the onset of a wide variety of psychopathologies such as depression and anxiety [5].

In addition to a ‘global’ (or trait) attachment style, adults have relationship-specific styles based on their different long-term relationships; attachment styles are hierarchically organised [10]. A person’s global style is the most cognitively available and accessible style at the top of the hierarchy, while relationship-specific attachment styles (to parents, siblings, etc.) are lower down the hierarchy [11]. Relationship-specific attachment styles can be reliably primed supraliminally or subliminally. Once primed, they drive information processing, feeling, and behaviour, similarly to global attachment style. Supraliminal priming techniques include visualisation, while subliminal techniques expose participants to security-related stimuli below conscious threshold [12].

Attachment Security Priming and Affect

Security priming has many positive personal and interpersonal effects, including the increase of self-esteem [13], prosocial values [14] and compassion and altruism [15]. It also reduces negative affect and increases positive affect [16,17,18].

We systematically reviewed the effectiveness of security priming compared to experimental and passive controls (no prime) in improving affect and considered the priming techniques and methods shown to be successful. We conceptualise affect as two separate constructs (positive vs. negative), reflecting the dominant approach in the literature and the one taken by the studies reviewed (defining our criteria for affect ensures the current systematic review is consistent, reliable and valid. Use of multiple models of affect [19] would compromise critical evaluation and comparisons between studies). Positive affect depicts feelings of pleasurable engagement with the environment such as happiness, excitement, and contentment [20]. Negative affect is defined as feelings of distress and unpleasurable engagement [21].

2. Method

2.1. Literature Search

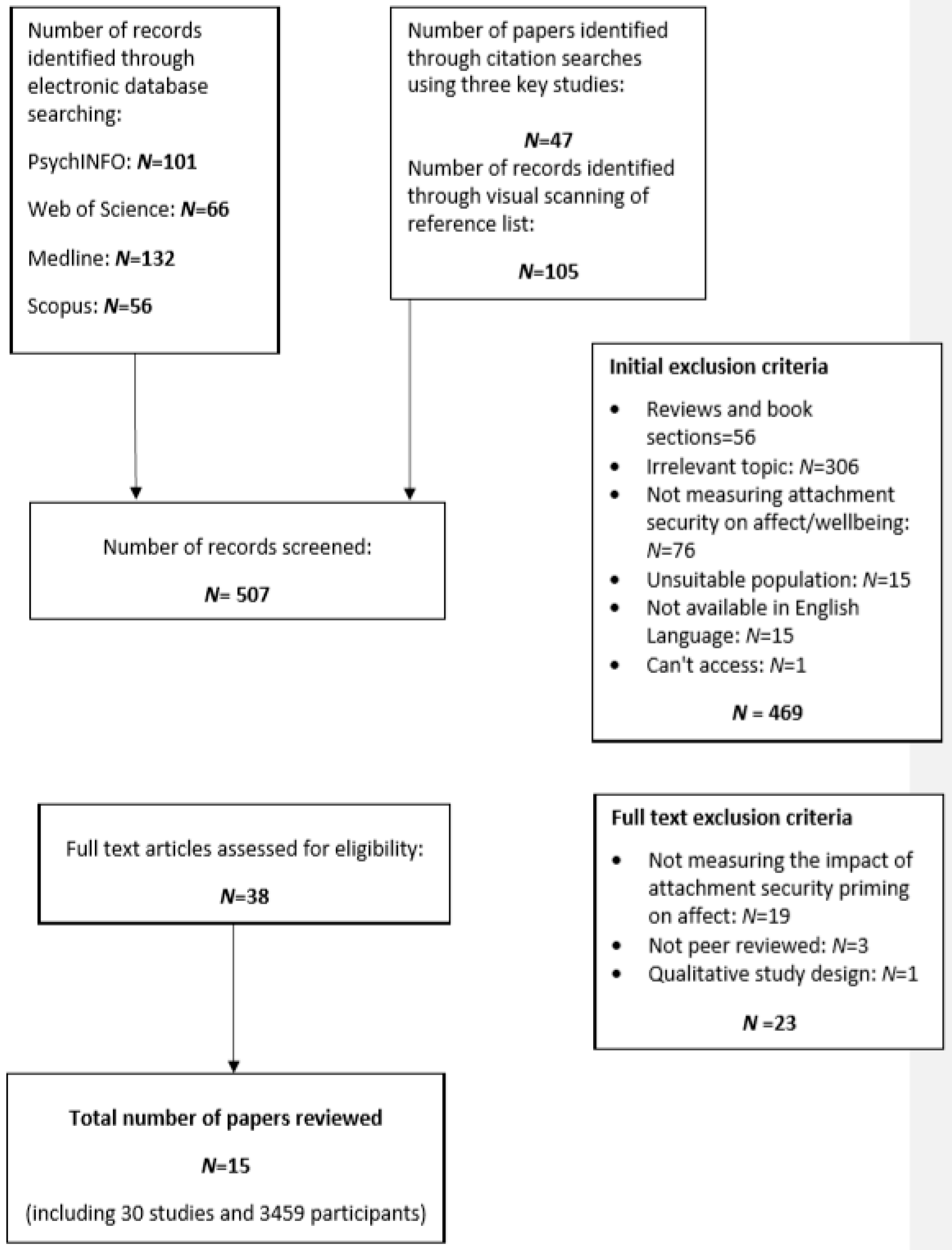

Four electronic databases were used: PsychINFO, Web of Science, MEDLINE and Scopus (see Figure 1). An initial search between July 2018 to August 2018 yielded 355 results (it should be noted that some of the results were duplicates so the number of unique papers was smaller.) (101 PsychINFO, 66 Web of Science, 132 MEDLINE, 56 Scopus). Backward and forward chaining techniques, including examining reference lists and citations in the three key studies most closely related to our systematic review question [22,23,24] yielded 196 papers, resulting in 507 results in total. Searches were conducted using the following terms (a) attachment security priming, (b) affect, and (c) children and adults. The search terms for attachment security priming included prime*, priming and attach* or secur*. They also included affect* or effect* (using the word ‘effect’ for affect was to allow for spelling mistakes that may have occurred.) or anxi* or depress* or positive mood or negative mood, child*, young person, adolescen*, teen*, young adult*, adult*.

Figure 1.

Chart of Search and Retrieval.

2.2. Screening Process

We used a two-step screening process to select the final papers. Step 1: Abstract and Method sections were screened for relevance. Step 2: Full texts were screened to determine whether the studies included attachment security priming to influence affect in the defined populations.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria specified that the articles be published in English and in peer-reviewed journals. Articles were excluded if they used animals, were unpublished or were reviewed. Further papers were excluded if they did not use priming to influence affect, were duplications from other databases, were unsuitable populations, or if a full text was not available. This resulted in 469 papers being removed. Of the remaining 38 papers, qualitative studies were excluded (23) leaving a final set of 15 papers and 30 studies (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Included in the Systematic Review.

2.4. Structure and Framework of Review

Eligible studies were quality assessed for strengths and weaknesses using an established checklist [34]. The framework consists of 27 questions, sub-divided into five categories: reporting, external validity, internal validity bias, internal validity (selection bias), and power.

3. Results

3.1. Research Methodology

Participants. Across studies 3459 participants received priming. The samples largely consisted of university students, but two tested child and adolescent participants [24], [26] (b), one a clinical sample [27], and one heterosexual romantic couples [29] (c). Most studies reported age ranges between 6 to 76 year, mean—21.9 years but not all [25], [29] (a–c), [30]. Studies were conducted in five countries: twelve in Israel [17] (a–e), [33] (a–g), ten in the US [24], [26] (a,b), [29] (a–c), [30,31], [32] (b), six in the UK [13,18], [22] (a,b), [25,27], one in China [16] and one in Canada [32] (a). The average percentage of females across studies was 64.3%. Studies inconsistently reported socio-demographic status and ethnicity.

Research design. Seventeen studies utilised a between-subject experimental design [13], [17] (a–e), [18], [22] (a,b), [24,25], [26] (b), [27,28,30], [32] (a,b) and five used a within-subject experimental design [29] (c), [31], [33] (b-d). Seven studies used mixed method designs [26] (a), [29] (a,b), [33] (a,e–g), and one adopted a quasi-experimental design [6].

Measures. A range of measures were used. All the studies utilised at least one self-report measure; the most popular was the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) [4], used in nineteen studies [13], [17] (a–e), [18], [22] (a,b), [25], [26] (a,b), [28], [29] (a–c), [30], [31]. Global attachment dimensions were used as either independent variables (IVs), dependent variables (DVs) or covariates. Alternative attachment measures were used, including the attachment story completion task [35,36] and a 10-item measure of attachment anxiety and avoidance [37,38] based on established measures [4]. The most common measures of affect were Profile of Mood States [39] in some studies [22] (a,b), [27] and the Implicit Positive and Negative Affect Test [40] in others [25], [29] (b,c). Additional measures included interpersonal experience or expectation [13], [17] (a–e), [18], [25], [28], felt security [41] in a few studies [13], [22] (a,b), [27] and attachment figure information in others [18,27], [33] (d). Two studies used heart rate monitoring, facial expression coding [24], and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans [31].

Effect sizes. Effect sizes for group differences were reported in 23 studies. The type of effect sizes used included partial eta squared (ηp2), eta-squared (η2), Cohen’s f2 and Cohen’s d [42]. Table 1 shows reported effects sizes, which have been classified as small, medium or large (following guidelines by [43,44].

3.2. Results by Type of Prime: Subliminal Primes

Sixteen studies employed a subliminal priming technique [17] (b–d), [24], [26] (a), [28,31], [32] (a,b), [33] (a–g). Of these, eleven used picture primes [17] (b,d), [24], [32] (a,b), [33] (a–c, e–g) and six used word primes [17] (c), [26] (a), [28,31], [33] (d,e).

Picture primes. Attachment security primes were pictures of a mother comforting her baby [24], [32] (a,b), [33] (a–c, e–g), a young heterosexual couple embracing [17] (b–d), [32] (a,b) and an elderly couple sitting close together [33] (c). Control primes (used in all 11 studies) varied, all used neutral (non-attachment relevant) pictures as a control, eight also used positive affect picture primes unrelated to attachment as controls, such as a beautiful natural scene [17] (b,d), [32] (b), [33] b,c, e–g), and four included a no picture (passive) condition [33] (a, e–g). Across studies, attachment security priming significantly reduced negative affect or increased positive affect in comparison to neutral or no picture controls. The effectiveness of positive affect priming relative to security priming varied; three studies found that positive affect primes [17] (b,d), [24] were less effective than attachment security primes, while three reported comparable results for the two primes [33] (a–c). Four studies manipulated participant stress and in these attachment security priming was more effective than positive affect priming [32] (b), [33] (e–g). Effect sizes ranged from medium [33] (a) to large [24], [33] (b,c, e–g).

Word primes. Six studies employed word priming tasks, including rating the similarity or liking of stimuli [26] (a), [28,31], [33] (d,e) and a lexical decision task [17] (c). Word primes included: common words related to attachment security versus neutral words [17] (c), [26] (a), [28,31], and names of the participants’ self-reported attachment figures versus names of close persons (but not attachment figures), associates and unknown individuals [33] (d). Three studies found attachment security word priming to be effective in reducing negative affect or increasing positive affect [17] (c), [28], [33] (d). Participants primed with attachment secure words reported significantly higher liking ratings for neutral stimuli [33] (d) and showed reduced maladaptive pain responses [28] compared to control words. They also showed reduced personal distress compared to a positive affect prime [17] (c). One study reported no differences between subliminally presented security word primes versus insecurity and neutral word primes in terms of participant responses to a prime manipulation check involving liking ratings of images [31] and another found that security word priming led to lower depressive symptoms when re-assessed one week later [26] (a). It should be noted however that the authors provided data on their combined subliminal and supraliminal findings, thus it was not possible to determine the distinct contribution of the subliminal prime alone.

Interaction with global attachment style. Eleven subliminal prime studies reported that global attachment style did not moderate the effects of prime [24], [26] (a), [28,31], [33] (a–g). Three studies, all designed to elicit empathy in the participant, reported that attachment anxiety moderated the effects of primed style [17] (b–d) but did not report effect sizes. Thus, for individuals high in global attachment anxiety, feelings of empathy rendered the secure prime less effective, maybe because empathy activated their global style which over-rode the prime.

3.3. Results by Type of Prime: Supraliminal Primes

Eighteen studies used a supraliminal priming technique [13,16], [17] (a,b,e), [18], [22] (a,b), [25], [26] (a,b), [27], [29] (a–c), [30,31], [33] (a).

Mental imagery task. Fourteen studies used mental imagery tasks [13,16], [17] (a,b,e), [18], [22] (a,b), [25], [26] (a,b), [27], [29] (a), [30]. Of these, 11 provided participants with a description of a secure attachment figure and asked them to think and/or write about the relationship/individual [13,16,18], [22] (a,b), [25], [26] (a,b), [27], [29] (a), [30] and 3 described a problematic interpersonal experience and asked participants to imagine they were in this situation and helped by an attachment figure [13], [17] (a,b). Eleven of the 14 studies found that security priming reduced negative affect or increased positive affect, relative to control [13], [17] (a,b), [18], [22] (a,b), [25], [26] (a,b), [27], [29] (a) and 3 studies reported no differences between the secure and neutral prime conditions in terms of anxious and depressed mood [22] (a), depressed mood [22] (b) and emotional wellbeing [30]. It should be noted that of the 11 studies in which the prime was effective, one did not reveal a statistical difference between the prime conditions [26] (b), one reported significant differences between prime conditions at one time point only [27] and two reported significant differences between prime conditions for one outcome variable only [29] (a), [30]. Based on seven studies, effect sizes ranged from medium [22] (a), [25,27] to large [13,16], [22] (b), [29] (a).

Picture or word task. Five studies used supraliminal pictures or word primes [26] (b), [29] (b,c), [31], [33] (a). All bar one [33] (a) reported reduced negative affect or increased positive affect in the secure prime condition relative to the control condition. Two studies used photographs of attachment figures, such as participants’ mothers [29] (b) or romantic partners [29] (c), two used picture or word primes related to attachment security [31], [33] (a). One study used a variety of security priming tasks: a picture writing task that required participants to describe a picture of a mother and baby, a study and recall of secure-themed sentences task, a secure word search task, and two visualisation/writing tasks in which participants wrote for 2 and 5 min about their secure experiences [26] (b). Interestingly, this study found that participants’ post-prime self-reported security differed as a function of prime type [26] (b), with the two visualisation tasks evoking higher security than the picture writing task. This suggests that mental imagery tasks in which participants are required to process information about their own attachment figures and/or attachment experiences, may be more effective than tasks that require the processing of information about an unknown other’s attachment secure interactions or experiences. Though it also should be noted that the participants in this study were teenagers (aged between 13–19 years) who may have found it challenging to relate to the experiences of mothers with babies. We cannot, therefore, rule out the possibility that the picture writing task may be more effective in older samples. Based on three studies that reported effect sizes, group differences between secure and control conditions were large [29] (b,c), [31].

Insecurity priming. Five supraliminal priming studies also primed attachment insecurity [17] (e), [18], [22] (a), [30,31]. Three found that primed insecurity led to greater negative affect than primed security [17] (e), [18], [22] (a), although primed avoidance did not result in greater depressed mood [22] (a) or higher personal distress [17] (e), compared to primed security. Furthermore, one study reported that priming anxious attachment led to small improvements in the participants’ positive affect over time, comparable to security priming [30]. None of the studies reported effect sizes.

Repeated priming. Five studies used repeated priming methodologies [13], [22] (b), [26] (b), [27,30]. One shot priming techniques have produced relatively short-lived effects [18,35]. In all five studies, the first subsequent prime was delivered 24 h after the initial prime. Two studies carried out an initial prime in the laboratory and then subsequent primes were delivered to participants via text message [22] (b), [27]. The remaining studies administered their initial and subsequent primes in the laboratory [13], in the participants’ naturalistic setting [26] (b), and/or via a study website [30]. Primes varied in length ranging from 3-min [22] (b), [27] to 10-min visualisations [13], [26] (b). Three of the studies kept their repeated primes constant and two used different primes [13], [26] (b). Studies generally reported that repeated security priming was effective in maintaining attachment security elevated over time [13,30]. One study showed a non-linear pattern to the effects of repeated security priming (e.g., lower state attachment security after the day 3 prime compared to the day 2 prime), possibly due to the differing efficacy of the different priming tasks used [26] (b).

Five studies measured the longer-term effects of security priming by administering post-prime dependent measures days, weeks or a month after the last prime [22], [26] (a), [27], [29] (c), [30]. Two studies collected dependent measures after each prime and at 24 h after the last security prime [22] (b), [27] and report that the secure prime resulted in higher felt security [22] (b), [27] and reduced anxiety and depression [22] (b), [27] compared to the neutral prime, at each time point. In both studies, however, reported security in the security prime group was lower at the final measurement relative to the previous time points. In other words, the positive effects of the secure prime appeared to decrease once participants were no longer exposed to it. Two studies collected post-prime dependent measures one week or more after the last prime was delivered [26] (a), [29] (c). One of these collected data one week after the last prime and found that self-reported depressed mood was significantly lower than at baseline for both secure and neutral priming conditions, although the decrease in the secure group was twice as large [26] (a). Another study measured post-prime emotional and physical health one month after the last prime and found that individuals primed with romantic partner (assumed to represent a secure attachment figure) experienced greater recovery in negative affect and continued to improve one month later [29] (c) (e.g., less physical pain and anxiety). Finally, a longitudinal study, involving priming attachment anxiety, security or a control every week for four months [30], showed reduced attachment anxiety over time in both the secure and anxious prime groups compared to the control group, while wellbeing and attachment avoidance were unaffected over time by prime. The security priming group also reported higher positive affect throughout the study than other control groups from the first measurement onwards.

Interaction with global attachment style. Fifteen supraliminal priming studies measured the interaction between primed and global attachment styles [13], [17] (a,b,e), [18,25], [26] (a,b), [27], [29] (a–c), [30,31], [33] (a). Eight reported no moderating effects of global style [13,18], [26] (a,b), [27,30,31,32], [33] (a) and two thirds of these used repeated priming designs. Three studies reported that global anxious style moderated the effects of primed style [17] (a,b,e). Congruent with the moderating effects of attachment anxiety in the subliminally presented security prime studies reviewed above, all three had dependent variables related to empathetic reactions to another persons’ plight. Furthermore, four studies reported that global avoidant style moderated the effects of primed style, diluting (weakening) the effect of the security prime weaker [25], [29] (a–c). Notably, none of these four studies used a repeated prime methodology.

3.4. Combining Subliminal and Supraliminal Priming Methods

Four studies used a combination of supraliminal and subliminal priming techniques. One reported that supraliminal and subliminal priming tasks similarly enhanced empathy and inhibited personal distress [17] (b) and another that they had comparable positive effects on depressive symptoms [26] (a). Conversely, one study found subliminal priming to be more effective than supraliminal priming [33] (a), while another found supraliminal priming to be more effective [31].

3.5. Quality Assessment

External validity. Samples were largely drawn from local universities and rewarded participation with course credits. Some studies used purpose sampling, based on characteristics of the population and research objectives [16,24], [26] (b), [27,31]. None reported the source population from which the sample was derived. Thus, it is not possible to determine the representativeness of samples. Furthermore, none provided information about whether the primes, staff or study materials were familiar to the participants, all of which could impact on the validity and reliability of the findings.

Internal validity. Most studies used reliable outcome measures (e.g., ECR, Profile of Mood States) and appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Analysis of Variance, t-Tests), and reported that the time between pre-measure, primes and follow-up were approximately consistent between participants. Nearly all studies using a repeated measure design controlled for order effects by counterbalancing their measures [29] (c), [33] (b–d)), apart from one study which omitted this information [31]. Most studies were carried out entirely under laboratory conditions which helped to standardise procedures, whilst other studies permitted participants to complete the procedure outside the laboratory [22] (b), [25], [26] (a,b), [27], [29] (a–c), [30]. Independent observer reports or task training were not reported in any of the studies, and only half included self-reports of prime task engagement or difficulty (e.g., the extent to which a participant felt engaged with the task or the ease with which a visualisation was achieved), or probed participants on the true purpose of the experiment afterwards [18], [29] (a–c), [33] (a–g). One study that did probe prime engagement [18] asked participants whether they were able to engage with the prime manipulation (e.g., rate on a scale of 1–7, the clarity of the visualisation during priming). Most studies stated that the participants were blind to their experimental condition, and a smaller number of studies used a double-blinded procedure [13,16], [33] (a–g). Filler questions or distraction tasks were used in approximately half of the studies to prevent the participant guessing the purpose of the research [13], [17] (a–e), [18], [22] (a,b), [24], [29] (a–c), [32] (a,b). Finally, only six studies conducted a manipulation check on felt security to determine whether the prime manipulation had successfully induced attachment security [13,18], [22] (a,b), [26] (b), [27].

Bias. Most studies suffered from a sampling bias as they recruited participants from local universities. Additionally, in most studies participants directly chose whether to be involved in the study, thus a self-selection bias occurred. Nearly all studies recruited participants from a single population, apart from two studies that used two different institutions or settings [13], [26] (b). Approximately half of the studies analysed group differences before administering the intervention in order to determine that the two groups were approximately equal in their baseline characteristics such as personality traits, socio-economic background, gender [13], [17] (a–e), [22] (a,b), [24], [26] (a,b), [27,31]. Data loss or exclusion was reported by half the studies [18], [22] (a,b), [24,25], [26] (a,b), [29] (a–c), [30], [32] (a,b), for reasons including missing responses, research errors, attrition, and exclusion due to failure to follow study instructions.

Power. Twenty studies reported power calculations to determine target sample size [17] (a–e), [22] (a,b), [25,27], [29] (a–c), [30], [33] (a–g). Sixteen studies were significantly powered to detect a large effect [17] (a–e), [22] (b), [25,27,30], [33] (a–g), whilst four studies were low on statistical power due to small samples sizes [22] (a), [29] (a–c).

3.6. Highest Rated Studies

The highest rated studies based on the quality checklist [34] were three [22] (b), [24,30]. The checklist produces a score from 0 to 27. The first [24] scored 23; notable strengths were their preliminary analyses to test for potential confounds, the use of multimodal assessment (e.g., physiological measurement instruments and self-report ratings) and the statistical procedures used to deal with missing data. The second [30] scored 22; strengths were the longitudinal design, high statistical power, and reporting of attrition analysis. The final study [22] (b) scored 22; strengths included their repeated prime methodology, attempts to blind participants to the outcomes of the experiment, and detailed reporting of statistical analyses, such as actual probability values and an explanation of how they dealt with outliers.

4. Discussion

The results of this systematic review suggest that attachment security priming effectively reduces negative affect and increases positive affect. Most studies report significant group differences (i.e., secure prime group compared to control groups) or within-participant differences post-intervention, with medium to large effect sizes. Studies used a range of methodologies and designs (e.g., within and between-participant experimental designs, subliminal and supraliminal priming techniques, one-time prime or repeated primes) and dependent and follow-up measures. Typically, questionnaires were used to measure attachment style, positive and negative affect, depression and anxiety, and felt security. Experimental designs generally compared an attachment security prime to a neutral, anxious or avoidant prime, although there was variability in priming procedures in terms of the frequency and time-lag. Overall, security priming in all its forms appeared effective in improving positive and reducing negative affect relative to control primes. This was the case across methods, designs, and dependent variables.

Comparable results were reported for both supraliminal and subliminal priming methods in reducing negative affect and increasing positive affect. That said, findings suggest that within each priming method some techniques may be better than others. The more effective supraliminal primes required participants to focus on (visualise and/or write about) their own attachment figures or experiences rather than attachment stimuli representing people or experiences outside their personal histories. Additionally, subliminal picture primes were more effective than word primes in increasing positive affect and decreasing negative affect. It should be noted, however, that only 6 studies used word primes and the only paper that used both subliminal words and pictures found them to be equally effective [33].

Notably, repeated priming studies suggest a cumulative positive effect of security priming over time. These designs, although more laborious, seem highly effective in keeping security elevated over time and can have long-lasting effects, up to a month after the last prime. Repeated priming may be particularly effective for insecure individuals, breaking down the defenses associated with insecurity over time to confer the benefits of security. Of the fifteen studies that examined whether the effects of the prime were moderated by global attachment style, approximately half reported this to be the case. Prime effects were moderated by both global avoidance and anxiety and mainly in one-shot prime studies. Moderation by global attachment anxiety was observed in one-shot prime studies involving empathy-evoking tasks. Such tasks may activate individuals’ global anxious attachment style because they induce feelings of distress [5]. Moderation by attachment avoidance was observed in one-shot prime studies involving diverse measures and dependent variables. These moderation effects further underline the value of repeated priming versus one-shot prime study designs. Repeated priming designs may be more effective than one-shot study designs in overcoming feelings of distress for individuals high in attachment anxiety and at penetrating the defensive mechanisms associated with global attachment avoidance.

4.1. Strengths of the Literature

It is a particular strength that most studies compared the experimental condition to an active control condition (where participants receive a similar intervention to the experimental group) as opposed to a passive control condition (in which no intervention is received). Passive controls can result in confounding variables and affect the validity of the study (e.g., amount of experimenter contact, expectancy effects and motivation [45], while active controls allow the possibility that participants may benefit from the alternative intervention [46].

Additional methodological strengths of studies reviewed were procedure randomisation, use of published self-report measures, blind condition assignment and matched group designs. One study applied a particularly strong methodology in a double-blind procedure [33] and another [22] reduced internal bias by blinding participants to the true study purpose. Within-subject design studies counterbalanced their trials to prevent order effects (although one did not report this information). Approximately two thirds of the studies examined the potential moderating effects of the prime by global attachment dimensions.

4.2. Limitations of the Literature

Methodological limitations included an over-reliance on university samples and female participants, effect sizes not being reported, limited recruitment of children or older adults, and studies measuring negative but not positive affect (and vice versa). In addition, most studies used self-report measures that are subject to recall, response bias (e.g., social desirability) and objectivity issues [47]. None of the studies distinguished between different types of avoidant attachment in priming avoidant style, potentially confounding fearful and dismissing attachment styles and their potential distinct effects on affect [48].

4.3. Future Research

Future research directions are suggested by the review. Firstly, future research might include post-intervention follow-up data collection over a longer term than has been done to date. This would allow researchers to determine whether security primes have long-term effects on outcomes and precisely how long these effects last. A general criticism of priming studies is that they produce short-term effects [49,50]. Repeated priming, however, seems to result in relatively longer lasting effects [51]. Indeed, the repeated priming studies reviewed here support this notion, showing that the positive priming effects can be maintained for several days post-prime. A next step for research is to use a repeated priming methodology with affect as the principle dependent variable and to include post-prime follow-ups in excess of 1-week post-last prime, (perhaps 1 month and 6 months post-last prime).

Secondly, attempts should be made to triangulate self-report questionnaires with assessment of the individuals’ behavioural and physiological measures in security priming studies. This would strengthen research findings [52] and point to physiological and behavioural benefits of attachment security priming. It would also allow the examination of potential physiological mediators or moderators of the effects of security of attachment on affect. It may be the case, for example, that the benefits of security priming for psychological wellbeing and affect are mediated by physiological effects.

Thirdly, given the mixed findings regarding the moderation of security priming by global attachment dimensions, well-powered longitudinal research is needed. If global attachment dimensions reliably moderate the effect of security priming this will have implications for study methods. For example, a longitudinal priming study could examine whether repeated security priming designs are more effective at overcoming the defensive emotion regulation strategies of individuals that are high in global avoidance than one-shot priming studies.

Fourthly, given the medium to large effect sizes that were generally reported, a meta-analysis of this literature, focusing on particular types of primes, for example, may be a fruitful future direction. Unfortunately, given the range of priming techniques and measures used across our reviewed studies, the aggregation of effect sizes would be minimally informative.

Finally, our results have clinical implications for people generally, but specifically too for young people and children. Only two studies in the current review were conducted with children and young people below 18 years old and this is an important direction for research. In 2017, the UK Office of National Statistics reporting that that one in eight children and young people (aged between 5 to 19 years old.) had a mental disorder (mental disorders were identified according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) to standardise diagnostic criteria. Mental Disorders were defined by symptoms that caused significant distress to children and young people or impaired their functioning.), and one in twelve had an emotional disorder such as anxiety or depression [53]. Future research should explore the impact of security priming with samples of children and young people with the aims of examining how to improve emotional wellbeing and of designing therapeutic and clinical interventions.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review represents the first thorough quality assessment of the literature on attachment security priming and affect. The findings reported herein will be useful to attachment researchers in designing future studies. Notably, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria helped to minimise the possibility of study selection bias.

While a small number of studies failed to observe priming influences on affect, overall, our findings show that security priming effectively reduces negative affect, increases positive affect and has beneficial effects across a diverse set of outcomes. The review points to the value of repeated security priming study designs, which may be more effective at breaking down the defenses associated with attachment insecurity, and the use of both subliminal and supraliminal security primes.

Author Contributions

Each author made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data and has approved the submitted version (and version substantially edited by journal staff that involves the author’s contribution to the study). A.C.R. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, analytic strategy, writing and editing of the current review. She was the lead on the writing of the manuscript also. E.R.G. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, analytic strategy, writing and editing of the current review. She conducted the main analysis for the study. K.B.C. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, analytic strategy, writing and editing of the current review. She also supervised the second author in conducting the review. All authors have been involved with the original draft preparation and subsequent reviews. Each author agrees to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and documented in the literature. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: Assessed in the Strange Situation and at Home; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, M.W.; Keelan, J.P.R.; Fehr, B.; Enns, V.; Koh-Rangarajoo, E. Social-cognitive conceptualization of attachment working models: Availability and accessibility effects. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Voleme 1: Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, K.A.; Clark, C.L.; Shaver, P.R. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships; Simpson, J.A., Rholes, W.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Volume 2: Separation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak, R.R.; Sceery, A. Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation, and representations of self and others. Child Dev. 1988, 59, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.A. Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquati, J.C.; Raffaelli, M. Daily experiences of emotions and social contexts of securely and insecurely attached young adults. J. Adolesc. Res. 2004, 19, 740–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.L.; Read, S.J. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.L.; Read, S.J. Cognitive representations of attachment: The structure and function of working models. In Advances in Personal Relationships: Attachment Processes in Adulthood; Bartholomew, K., Perlman, D., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1994; pp. 53–92. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Draine, S.C.; Abrams, R.L. Three cognitive markers of unconscious semantic activation. Science 1996, 273, 1699–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnelley, K.B.; Rowe, A.C. Repeated priming of attachment security influences later views of self and relationships. Pers. Relatish. 2007, 14, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Boosting attachment security to promote mental health, prosocial values, and inter-group tolerance. Psychol. Inq. 2007, 18, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillath, O.; Shaver, P.R.; Mikulincer, M. An attachment-theoretical approach to compassion and altruism. In Compassion: Conceptualisations, Research and Use in Psychotherapy; Gilbert, P., Ed.; Brunner-Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X. Effect of priming with attachment security on positive affect among individuals with depression. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Gillath, O.; Halevy, V.; Avihou, N.; Avidan, S.; Eshkoli, N. Attachment theory and reactions to others’ needs: Evidence that activation of the sense of attachment security promotes empathic responses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 1205–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, A.; Carnelley, K.B. Attachment style differences in the processing of attachment relevant-information: Primed-style effects on recall, interpersonal expectations, and affect. Pers. Relatish. 2003, 10, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, J.; Russell, J.A.; Peterson, B.S. The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressman, S.D.; Cohen, S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, J.R.; Henry, J.D. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 43, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnelley, K.B.; Otway, L.J.; Rowe, A.C. The effects of attachment priming on depressed and anxious mood. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 4, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otway, L.J.; Carnelley, K.B.; Rowe, A.C. Texting “boosts” felt security. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2014, 16, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupica, B.; Brett, B.E.; Woodhouse, S.S.; Cassidy, J. Attachment security priming decreases children’s physiological response to threat. Child Dev. 2017, 90, 1254–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Chan, I. Activating attachment representations during memory retrieval modulates intrusive traumatic memories. Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 55, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, A.B.; Gillath, O.; Jackson, Y.; Ingram, R. Attachment security priming as a potential intervention for depressive symptoms. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 37, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnelley, K.B.; Bejinaru, M.M.; Otway, L.; Baldwin, D.S.; Rowe, A.C. Effects of repeated attachment security priming in outpatients with primary depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 234, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J.; Shaver, P.R.; Mikulincer, M.; Lavy, S. Experimentally induced security influences responses to psychological pain. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 28, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selcuk, E.; Zayas, V.; Günaydin, G.; Hazan, C.; Kross, E. Mental representations of attachment figures facilitate recovery following upsetting autobiographical memory recall. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, N.W.; Fraley, R.C. Moving toward greater security: The effects of repeatedly priming attachment security and anxiety. J. Res. Personal. 2018, 74, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canterberry, M.; Gillath, O. Neural evidence for a multifaceted model of attachment security. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2012, 88, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, D.G.; Lane, R.A.; Koren, T.; Bartholomew, K. Secure base priming diminishes conflict-based anger and anxiety. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Hirschberger, G.; Nachmias, O.; Gillath, O. The affective component of the secure base schema: Affective priming with representations of attachment security. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.H.; Black, N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 1998, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartz, J.A.; Lydon, J.E. Close relationships and the working self-concept: Implicit and explicit effects of priming attachment on agency and communion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, I.; Ridgeway, D.; Cassidy, J. Assessing internal working models of the attachment relationship. Attach. Presch. Years Theory Res. Interv. 1990, 273, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Florian, V.; Tolmacz, R. Attachment styles and fear of personal death: A case study of affect regulation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnelley, K.B.; Pietromonaco, P.R.; Jaffe, K. Depression, working models of others, and relationship functioning. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, D.M.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L.F. Profile of Mood States; Educational and Industrial Testing Service: San Diego, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Quirin, M.; Kazén, M.; Kuhl, J. When nonsense sounds happy or helpless: The implicit positive and negative affect test (IPANAT). J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, M.A.; Sedikides, C.; Carnelley, K. Your love lifts me higher! The energizing quality of secure relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrlik, J.W.; Williams, H.A. The incorporation of effect size in information technology, learning, information technology, learning, and performance research and performance research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2003, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, J.; Shevlin, M. Applying Regression and Correlation: A Guide for Students and Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Redick, T.S.; Shipstead, Z.; Wiemers, E.A.; Melby-Lervåg, M.; Hulme, C. What’s working in working memory training? An educational perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, R.; Ellenberg, S.S. Medicine and public issues. Ann. Int. Med. 2000, 133, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenman, R.; Tennekoon, V.; Hill, L.G. Measuring bias in self-reported data. Int. J. Behav. Healthc. Res. 2011, 2, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joordens, S.; Becker, S. The long and short of semantic priming effects in lexical decision. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1997, 23, 1083–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wheeldon, L.R.; Smith, M.C. Phrase structure priming: A short-lived effect. Lang. Cognit. Proc. 2003, 18, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.S. Single and multiple test repetition priming in implicit memory. Memory 1996, 4, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeil, B.M.; Lopes, V.A.; Minnes, P.M. Anxiety in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K.; Vizard, T.; Ford, T.; Marcheselli, F.; Pearce, N.; Mandalia, J.D.; McManus, S. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England. 2017. Available online: https://gss.civilservice.gov.uk/wp- (accessed on 13 February 2019).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).