“And Then He Got into the Wrong Group”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Effects of Randomization in Recruitment to a Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

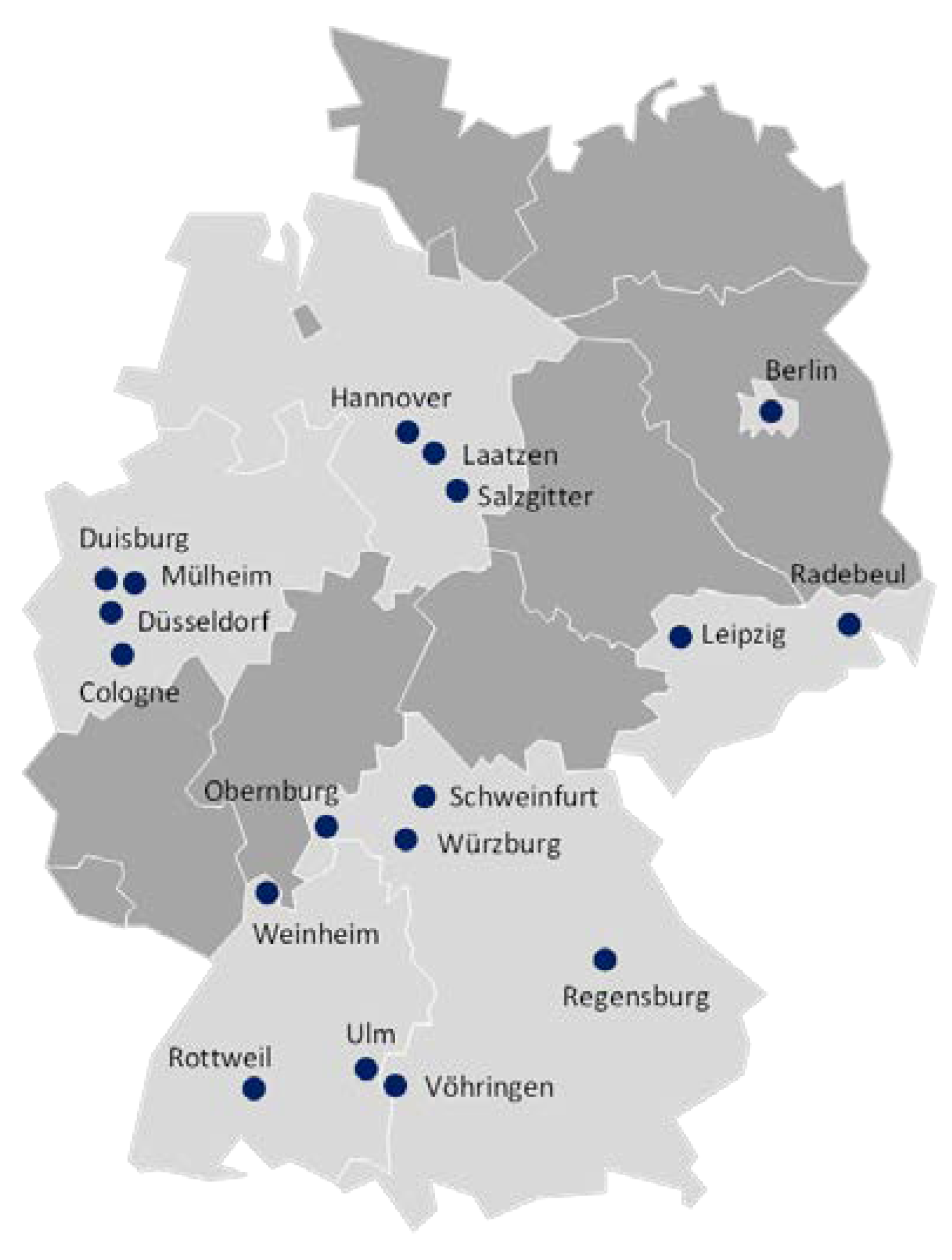

2.1. Setting

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect on Case Managers

3.1.1. How Do They Deal with the Randomization Design?

Communication with Participants

[…] On the basis of the meetings, I contact the insured person, inform them, and tell them from the beginning, it will go like this and that and that, and there are two comparison groups. And so far, I personally haven’t had any negative experiences. […](CM11, FG2)

Precisely. It is harder to convey this to them (participants who expect to be allocated to the treatment group) in this study and that I don’t really have any influence on it. That’s the very problem.(CM16, FG3)

It takes a long time, the whole conversation is more difficult, effortful and considerably longer, because you totally have to fight for this self-management and in the end, the client doesn’t lose anything, when they participate. On the contrary. In any case, it is very, very difficult to start, when you do not start at zero, but somewhere completely different, where someone wants to get this case management at all costs. […](CM12, FG2)

You also have, if I may say something about this briefly, different expectations. Whether the insured person has read a poster or whether they come to us directly and only get into the self-supporting group. Then the disappointment will be greater than when I approach them at the counter and explain the project. […](CM16, FG3)

Strategies to Cope with Randomization

The other one is to give advice much more neutrally and they will be satisfied with their solution, because it’s about them. They then know, okay, the employee from the health insurance fund cares about me and found a solution for me, or at least has a point of departure to do something about their problem. If and how it helps, that’s another story. […](CM16, FG3)

When the HR advisors send us people, they tell them they have something, go to the health insurance. And when they then come back, ‘they didn’t have anything’. Difficult. We now try to compensate for that. What does compensate mean? We offer different interventions, so that there is something to it and slowly people are coming.(CM15, FG3)

In our case it’s like that, we actually got that from you (CM7), with this folder and we primarily have it for the self-management group, a folder with the logo on the front and we put in it all the ideas from health insurance fund X, price reductions in the gym, what we can offer, all the prevention courses, rehabilitation sport. And then we give them the folder, the Thera-band, the information leaflet and the questionnaire and then they don’t just leave the room with a Thera-band.(CM13, FG3)

But then the group comparison is not worth anything anymore. When you take the control group, which has the self-management and give them something else anyway, then you cannot compare them anymore.(CM13, FG3)

Because we had the problem, if they got into the self-management group we said: Don’t randomize.(CM5, FG1)

3.1.2. How Do Case Managers Perceive Randomization?

Comprehension Study Design

In our case, or in my case, when I conduct the conversations, I couldn’t say that they are really disappointed, because I try beforehand to point out that we need both groups to get a result in the end. […](CM18, FG3)

And then the fact that I don’t have an influence over the randomization and that the result is always a surprise. However, I realized that there is a pattern. That means, when I know the last person got into the case management group, then I know that the next person will get into the self-management group. This is the pattern that I have seen in my case.(CM4, FG1)

Group Perception

In general, everyone at Company X thinks the project is great and we would be really happy if it would really start soon (inclusion of participants), so that we can also do some good for the insured people, of course. And we’ll see what the future brings.(CM11, FG2)

Many of those who I had in this project are employees who have problems but hadn’t done anything about them yet. For them, it was a good starting point and they are partly done with the program and want to continue to do something for their health. The initial test also already had some positive feedback, especially in pain reduction and then the indication to do something about one’s health.(CM15, FG3)

I don’t know, it might also be a bit dependent on the clientele. In our case, they are almost all men. It’s a factory, where it’s hands-on, a lot of physical work. Accordingly, they are (blue collar) workers, who are comparably robust, some may be already a bit overweight. Basically, it’s the working class. They are around 40, 50 years of age, and some have back problems. […] When you have someone like this standing in front of you, comparably robust and so on, a Thera-band isn’t really hip/fancy. Then they are already looking at me funny. And it’s simply, a man will also be less likely do a yoga course or something and it’s the same with the Thera-band. It somehow doesn’t fit with the clientele. It’s the same with rehab. When I have a young person, they would rather train on fitness equipment than lie on the mat and do exercises. That’s how it is. There are exceptions, but usually, it’s like that.(CM10, FG2)

There was a wish expressed to get into the self-management group. Exactly, because in my case mechanics say ‘Then I’d rather do my exercises at home and then I don’t need to … because I’m away. I couldn’t do it.’ That also exists. It’s rare, but it exists.(CM6, FG1)

I think that it’s simply because they need help now, and they want help now, and I promised something, we will do something, and this Thera-band is simply too little. It is really incredible. Well, there is something—they want something, that’s why they came and then they basically get nothing.(CM20, FG3)

When they’re getting into the wrong group … unfortunately it happened. Stupid.(CM5, FG1)

You try to have the conversation end well. […] I’ll try to sell it more neutrally now.(CM20, FG3)

Well, it is a 50/50 chance.(CM5, FG1)

3.1.3. How Does It Make Them Feel?

Emotional Reaction

Yes, there needs to be a sense of achievement at some point, when you bend over backwards like that.(CM5, FG1)

With the first two, three, I was pretty disappointed, because they all got into the self-management group. So, everyone immediately got into the wrong group.(CM5, FG1)

Gosh, it doesn’t really bother me to be honest. It’s not my fault.(CM16, FG3)

3.1.4. What Is the Perceived Impact for the (Insurance) Company?

Impact Reputation

We now also have three that are training, but luckily everything is very positive, and that news spreads, and they really had good experiences. Two are already finished, have completed it, and really say that their pain decreased in the shoulder and knee and they are really satisfied. Luckily, this news also spreads […](CM20, FG3)

It was a bit tough to start with, because my first three got into the self-management group and the rumors spread: ‘You don’t need to go there, you’ll only get into the self-management group.’(CM15, FG3)

Because we asked ourselves not long ago, whether we would do such a project again and at the moment, we are actually really thinking that the risk of damaging the image is higher than I can say is a positive thing, at this moment. But that’s a very subjective estimation at the moment. We have to wait and see if it turns out to be effective. But it’s simply, definitely associated with quite a risk, which can be destroyed in such a factory.(CM14, FG3)

3.2. Effect on Participants

3.2.1. How Do They Perceive the Randomization and Allocation into Groups?

Comprehension (Necessity Study)

Well, I also have this problem that I often really have the feeling, they simply don’t understand this study design. […] I regularly get people from the self-management group, who regularly call me and ask me, ‘What else can I do, when can I start the training?’ I’ve got a schedule, where it’s actually written out pretty clear that it starts after one year, but understanding the system a little bit, is really, really hard for a lot of them.(CM7, FG3)

Group Perception/Expectations

In my case, everybody wants to get into the case management group. I didn’t have a single person who said: ‘Gosh, a little bit of exercising at home.’ … No.(CM5, FG1)

And I, by the way, heard from a worker that told me ‘Case management twelve times or two times a week over twelve weeks, I can’t do it. I could do a bit at home.’ So, this type also exists, who says: ‘No, I wouldn’t go anywhere. I would do something at home.’(CM4, FG1)

I already heard: ‘I mean, if I’m unlucky, I’ll get nothing from you.’(CM12, FG2)

What got better, I’m going back in time a bit, is that ever since the letters were out and it didn’t go through the occupational physicians anymore, they (participants) call us directly and we can give them the first/initial information. That means that they don’t come to the appointment with the wrong expectations. I find that helpful.(CM8, FG2)

[…] I think that the more who are going to participate, the higher the expectations: ‘I want to go there (training center), so why do I get the Thera-band?’ I think it will get worse. I don’t think it will get better.(CM20, FG3)

3.2.2. How Do They React?

(Emotional) Reactions

In our case, or in my case, when I lead the conversations, I couldn’t say that they are that disappointed. Because I try to point out from the start that we need both groups to get the results in the end. So that’s why I couldn’t really say that there’s a lot of disappointment. Of course, with Module A, it isn’t the nicest option that you can only start the training after one year, but generally, they receive the news positively, in my experience.(CM18, FG3)

[…] Giant disappointment. That someone dropped out immediately. Immediately said, you can throw away that piece of paper, he’s dropping out. Such a stupid Thera-band, he’s got that at home himself and he also has an exercise machine at home that he never sits on. […] They are utterly disappointed. I’ve now got three in the self-management group, as I said, one of them dropped out, the second one I couldn’t get a hold of, I haven’t heard anything. He also went out with the Thera-band and was utterly disappointed.(CM20, FG3)

[…] He slammed the door in the end and said: ‘This is bullshit that I get into the self-management group, I need the work-related rehab. Everything else is bullshit for me.’ And he really got louder, and I was really, really glad when he was gone. He also didn’t fill in the questionnaire. But I knew at the beginning that he wouldn’t do that. But he really got angry and … yes.(CM7, FG3)

Yes, I guess, those are the ones you don’t get anything back from. Or also the administration I guess, if I’m not in the project (group) that I want, I think that partly they don’t send anything back. Some are just sitting it out, and also in the case management group. (Person Y, project leader) also said we should ask them about it. But I can write to them, I can call them, they won’t pick up the phone anymore. […](CM2, FG1)

Impact on the Study

In my case, he really got into the wrong group. He really wanted to get into the case management group, Module A and got into the self-management group. I did get angry. Okay. Then he says: ‘Yes, okay, well.’ Then I said: ‘You can, as my colleague told you, get into the case management training after twelve months, that’s no problem.’ ‘Yeah, okay.’ Two days later, three days later, I got a call: ‘Ah, (name case manager). Ah, somehow, no, I’d rather …’ so I said: ‘I can’t force you to do it. If you don’t want to do it …’(CM3, FG1)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muche, R.; Rohlmann, F.; Büchele, G.; Gaus, W. The use of randomisation in clinical studies in rehabilitation medicine: Basics and practical aspects. Rehabilitation 2002, 41, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Peters, T.J.; Brindle, L.; Salter, E.; Gillatt, D.; Powell, P.; Bollina, P.; Neal, D.E.; Hamdy, F.C.; et al. Development of a complex intervention improved randomization and informed consent in a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, J.L.; Paramasivan, S.; de Salis, I.; Toerien, M. Clear obstacles and hidden challenges: Understanding recruiter perspectives in six pragmatic randomized controlled trials. Trials 2004, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ioannidis, J.P. Why most clinical research is not useful. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halpern, S.D. Prospective preference assessment: A method to enhance the ethics and efficiency of randomized controlled trials. Control. Clin. Trials 2002, 23, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, A.M.; Knight, R.C.; Campbell, M.K.; Entwistle, V.A.; Grant, A.M.; Cook, J.A.; Elbourne, D.R.; Francis, D.; Garcia, J.; Roberts, I.; et al. What influences recruitment to randomized controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials 2006, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliott, D.; Husbands, S.; Hamdy, F.C.; Holmberg, L.; Donovan, J.L. Understanding and improving recruitment to randomised controlled trials: Qualitative research approaches. Eur. Urol. 2017, 72, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, M.; Nazareth, I.; Lampe, F.; Bower, P.; Chandler, M.; Morou, M.; Sibbald, B.; Lai, R. Impact of participant and physician intervention preferences on randomized trials. A systematic review. JAMA 2005, 293, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, B.; Gheorghe, A.; Moore, D.; Wilson, S.; Damery, S. Improving the recruitment activity of clinicians in randomized controlled trials: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pohontsch, N.J.; Müller, V.; Brandner, S.; Karlheim, C.; Jünger, S.; Klindtworth, K.; Stamer, M.; Höfling-Engels, N.; Kleineke, V.; Brandt, B.; et al. Group discussions in Health Services Research—Part 1: Introduction and deliberations on selection of method and planning. Gesundheitswesen 2018, 80, 864–870. (In German) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health C 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bill-Axelson, A.; Christensson, A.; Carlsson, M.; Norlén, B.J.; Holmberg, L. Experiences of randomization: Interviews with patients and clinicians. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 42, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, C.; Stavropoulou, C. Specialist nurses’ perception of inviting patients to participate in clinical research studies: A qualitative descriptive study of barriers and facilitators. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lamb, K.A.; Backhouse, M.R.; Adderley, U.J. A qualitative study of factors impacting upon the recruitment of participants to research studies in wound care—The community nurses’ perspective. J. Tissue Viability 2016, 25, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, C.; Gray, S.; Selley, S.; Bowie, C.; Price, C. Clinicians’ attitudes to recruitment to randomized trials in cancer care: A qualitative study. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 2000, 5, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.; Kramo, K.; Soteriou, T.; Crawford, M.J. The great divide: A qualitative investigation of factors influencing researcher access to potential randomised controlled trial participants in mental health settings. J. Ment. Health 2010, 19, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebland, S.; Featherstone, K.; Sowdon, C.; Barker, K.; Frost, H.; Fairbank, J. Does it matter if clinicians don’t understand what the trial is really about? Qualitative study of surgeons’ experiences of participation in a pragmatic multi-centre RCT. Trials 2007, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donovan, J.L.; de Salis, I.; Toerien, M.; Paramasivan, S.; Hamdy, F.C.; Blazeby, J.M. The intellectual challenges and emotional consequences of equipoise contributed to fragility of recruitment in six randomised controlled trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paramasivan, S.; Huddart, R.; Hall, E.; Lewis, R.; Birtle, A.; Donovan, J.L. Key issues in recruitment to randomised controlled trials with very different interventions. A qualitative investigation of recruitment to the SPARE trial (CRUK/07/011). Trials 2011, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rooshenas, L.; Elliott, D.; Wade, J.; Jepson, M.; Paramasivan, S.; Strong, S.; Wilson, D.; Beard, D.; Blazeby, J.M.; Birtle, A.; et al. Conveying equipoise during recruitment for clinical trials: Qualitative synthesis of clinicians’ practices across six randomised controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cook, C.; Sheets, C. Clinical equipoise and personal equipoise: Two necessary ingredients for reducing bias in manual therapy trials. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2011, 19, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanson-Fisher, R.W.; Bonevski, B.; Green, L.W.; D’Este, C. Limitations of the randomized controlled trial in evaluating population-based health interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn-Thomas, H.A.; McGreal, M.J.; Thiel, E.C.; Fine, S.; Erlichman, C. Patients’ willingness to enter clinical trials: Measuring the association with perceived benefit and preference for decision participation. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, L.Y.; Seligman, M.E.; Teasdale, J.D. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. J. Abnorm. 1978, 87, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keedy, N.H.; Keffala, V.J.; Altmaier, E.M.; Chen, J.J. Health locus of control and self-efficacy predict back pain rehabilitation outcomes. Iowa Orthop. J. 2014, 34, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janevic, M.R.; Janz, N.K.; Dodge, J.A.; Lin, X.; Pan, W.; Sinco, B.R.; Clark, N.M. The role of choice in health education intervention trials: A review and case study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 1581–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, L.N.; Flynn, T.W. Placebo, nocebo, and expectations: Leveraging positive outcomes. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 43, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lehmann, B.A.; Lindert, L.; Ohlmeier, S.; Schlomann, L.; Pfaff, H.; Choi, K.-E. “And Then He Got into the Wrong Group”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Effects of Randomization in Recruitment to a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061886

Lehmann BA, Lindert L, Ohlmeier S, Schlomann L, Pfaff H, Choi K-E. “And Then He Got into the Wrong Group”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Effects of Randomization in Recruitment to a Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061886

Chicago/Turabian StyleLehmann, Birthe Andrea, Lara Lindert, Silke Ohlmeier, Lara Schlomann, Holger Pfaff, and Kyung-Eun Choi. 2020. "“And Then He Got into the Wrong Group”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Effects of Randomization in Recruitment to a Randomized Controlled Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061886

APA StyleLehmann, B. A., Lindert, L., Ohlmeier, S., Schlomann, L., Pfaff, H., & Choi, K.-E. (2020). “And Then He Got into the Wrong Group”: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Effects of Randomization in Recruitment to a Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 1886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061886

_Choi.png)