1. Introduction

Properly maintaining and adjusting to school life is very important during adolescence [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends daily physical activity for more than 60 min for teens aged 15 to 17. This is because teenagers’ participation in physical activities will help them adapt to school life [

5]. However, student-athletes have adjustment difficulties when their activities exceed the WHO-recommended amount [

6,

7]. Among Korean students, the general dropout rate is less than 1%, but when considering only student-athletes, over 40% abandon athletic activities before graduation. When including those who do not enter professional sports post-graduation, the abandonment rate reaches nearly 90% [

8]. These student-athletes also cannot adjust to school life, resulting in >50% transference rate and 11% dropout rate. Furthermore, over half (51.6%) the students stop sports without any external extenuating circumstances [

9]. Student-athletes may have more difficulty in adjusting because of several intrinsic characteristics that should be considered when developing assistance programs [

10]. As the curriculum in Korea consists of 6 years of elementary school, 3 years of junior high school, and 3 years of high school, it is necessary to adapt to the new environment whenever the class changes. Student athletes in particular have less time to socialize with their classmates due to the inclusion of morning training programs before the first class, after-school training programs, and special training during the competition season. Psychological factors affect girls more than boys [

11], while sex-based physical differences also influence adjustment capacity [

12]. Additionally, student-athlete success is highly dependent on sporting achievements, and excellent performance in competitions [

13] and winning awards increases their likelihood of pursuing a sporting career post-graduation [

14]. Taken together, these findings indicate that gender and career awards won should be considered when investigating student-athlete adjustment to school.

Only one study is available on Korean student-athletes [

15], but it has a major limitation because participation guarantees the right to study. Therefore, voluntary compensation factors such as academic achievement are not considered despite being an important psychological factor affecting school adjustment [

16]. Psychological factors are more effective than behavioral factors at inducing school adjustment [

17] and, therefore, should be considered for student-athletes.

High self-concept (positive collection of beliefs about oneself) is linked to better academic and social achievement [

18] because it is a variable that affects mental state, psychological well-being, and behavior in adolescents [

4,

19]. Psychological variables are based on self-assessment. A person with a high self-concept is highly accomplished in academic or social life [

20]. Research has found that self-concepts are important factors in school life that affect mental state, psychological well-being, and human behavior [

21]. However, the measurement factor of the existing self-concept was developed for general students, so it is difficult to apply it to student athletes who have a different culture from general students [

22,

23]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify and apply physical self-concept factors appropriate to the characteristics of student athletes. This is because athletes have a better understanding of the body than others to achieve the best performance [

23]. Another caveat to consider is that due to differences in curriculum and school life culture, self-concept scales developed in other countries may not transfer to Korea, [

24]. Therefore, in this study, we intend to examine the effect of physical self-concept criteria, which has been validated in Korea, on students’ adjustment to school life according to the characteristics of students (gender and award experience).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the results of the factorial analysis to confirm the validity of physical self-concept. Participants responded using a five-point Likert scale (“1 = Not at all” to “5 = Very true”). A high total score indicates high physical self-concept. The questionnaire was both reliable and valid (SCO, α = 0.873; HP, α = 0.846, PA, α = 0.850).

Table 1. In addition, feasibility has been ensured through exploratory factor analysis and verbatim factor analysis, all of which exceed the standard values.

Table 2 shows the results of the factorial analysis to confirm the validity of School Adjustment Scale. Participants responded using a five-point Likert scale (“1 = Not at all” to “5 = very true”). A high score indicates better school life adjustment. The questionnaire was reliable and valid (TRE, α = 0.806; SRE, α = 0.792, SCL, α = 0.839, SRU, α = 0.872).

Table 2. In addition, both exploratory and ascertained factors analysis have met the model adequacy values.

The demographic characteristics of this study are as follows. Male participants (

n = 372; 63.2%) outnumbered the female participants (

n = 217; 36.8%) 155 men participated, 1.3 times more than women. Additionally, 47% (278) were middle school students and 52.8% (311) were high school students (

Table 3). More student-athletes did not win awards in their career (

n = 329; 55.9%) than those who did (

n = 260; 44.1%). For physical self-concept, students scored highest on PA (M = 4.36, SD = 0.618), then HP (M = 4.06, SD = 0.686), and finally SCO (M = 3.84, SD = 0.727). For school adjustment, they scored highest on SRE (M = 4.00, SD = 0.553) and lowest on SRU (M = 3.56).

Table 4 shows the average score of school adaptation according to the concept of physical self, and there found a statistically significant difference. Student athletes who best adapted to school classes were those with high physical activity (M = 3.64, SD = 0.403; F = 9.049,

p = 0.001). Student athletes with the best relationship with teachers were those with a high level of perception on health promotion (M = 6.37, SD = 0.325; F = 19.636,

p = 0.001). Students with good friendship with schoolmates were also the groups with high levels of awareness of health promotion (M = 6.04, SD = 0.353; F = 17.130,

p = 0.001). Finally, the group that adheres well to school rules was found to have a higher awareness of health promotion (M = 3.84, SD = 0.269; F = 14.252,

p = 0.001).

Table 5 shows the correlation between factors. All physical self-concept and school adjustment variables positively correlated, with the strongest relationship being between SCO and PA (r = 0.643,

p < 0.001) and the weakest, between HP and SCL (r = 0.224,

p < 0.001). Multicollinearity was not an issue because no correlation coefficients were over 0.800.

Linear regression revealed that among girls, higher SCL corresponds to SCO (β = 0.296,

p < 0.001), while higher SCL corresponds to HP (β = 0.233,

p < 0.001), and higher TRE corresponds to PA (β = 0.282,

p < 0.001) respectively. Among boys, higher TRE corresponds to SCO (β = 0.366,

p < 0.001), while higher SCL corresponds to PH (β = 0.264,

p < 0.001), and higher SRE corresponds to PA (β = 0.128,

p < 0.001) respectively (

Table 6).

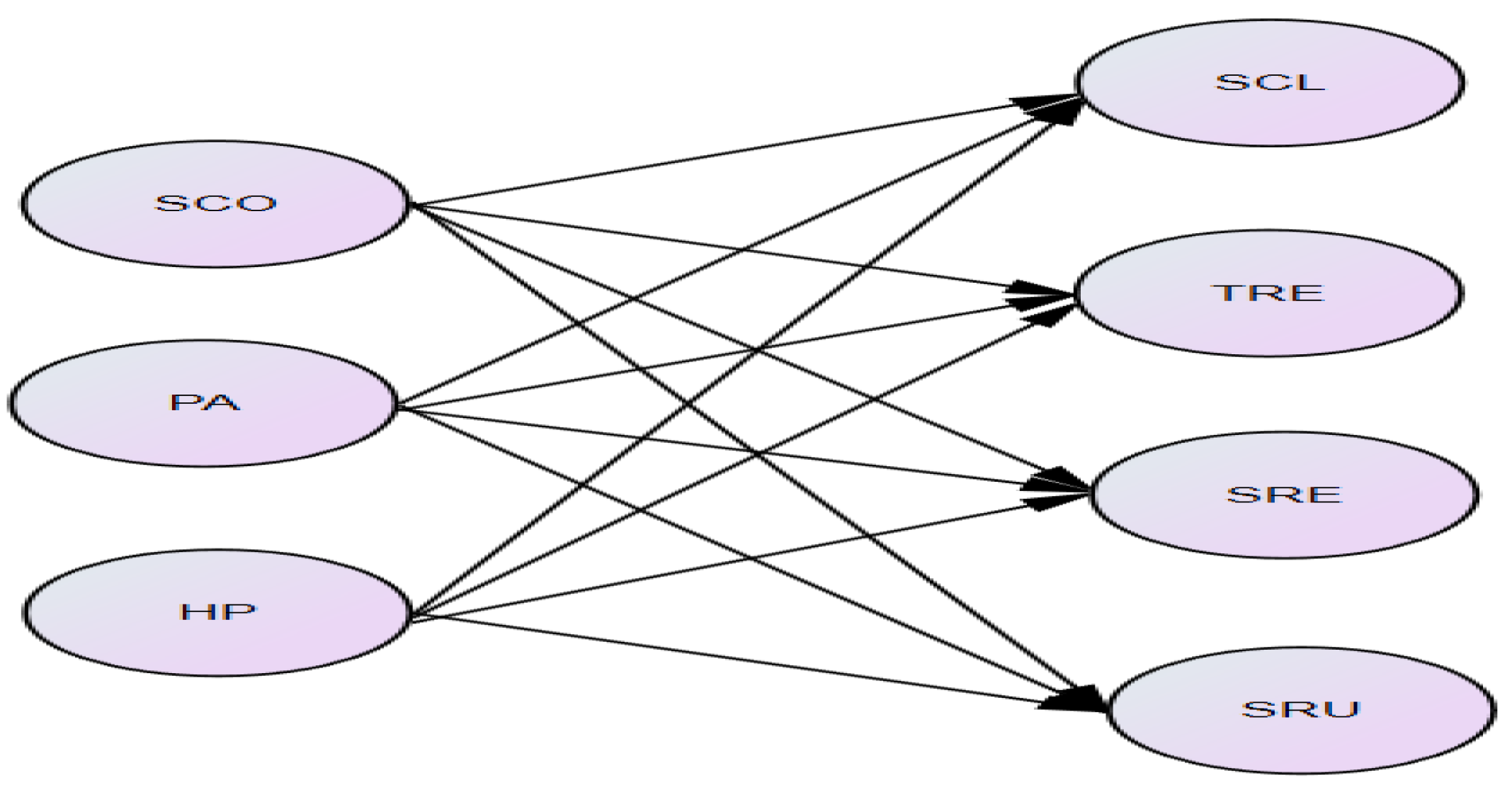

Figure 2 shows the effect of physical self-concepts on school adaptation based on sex.

Among students with an award-winning career, higher TRE corresponds to SCO (β = 0.352,

p < 0.001), while higher SCL corresponds to HP (β = 0.262,

p < 0.001), and higher SRE corresponds to PA (β = 0.243,

p < 0.001) respectively. Among those who did not win awards, higher TRE corresponds to SCO (β = 0.267,

p < 0.001), while higher TRE corresponds to HP (β = 0.299,

p < 0.001), and higher TRE corresponds to PA (β = 0.165,

p < 0.001) respectively (

Table 7).

Figure 3 shows the effect of physical self-concepts on school adaptation based on award-winning career.

4. Discussion

This study verified the effect of physical self-concept on the adaptation of school life in student athletes through gender and award experience. However, this sample was recruited by expedient sampling, so you should be careful about the dissection.

Higher SCO is correlated with higher TRE. High-performing players have a good relationship with coaches and their parents. This is more evident in younger players [

26,

27]. Relationships with others are built on trust. In other words, because the goal of both players and coaches is to achieve good results, high-achieving student players have a lot of experience in winning, which gives them confidence in their coaches, which has the same effect on others who lead them [

20]. Higher SCO was correlated with higher TRE, consistent with previous findings [

28] indicating that life-skill coaching benefits sports participation. Similarly, another study demonstrated that student-athletes perform better when they communicate constantly with and seek direction from their managers [

29]. Thus, we can conclude that a good relationship with coaches could allow student-athletes to form similar bonds with teachers, benefiting school life adjustment.

Analysis of the correlation between physical self-concept and school life adaptation showed that the high physical self-concept of student athletes had a positive effect on their school life adaptation. These results reflect that the higher the physical self-concept of student athletes, the better their adjustment to class and rules and their relationship with teachers and classmates [

29]. In other words, because student athletes understand their body, psychological factors such as self-esteem and sense of achievement are high [

28]. This study’s finding regarding the effects of positive psychological factors is identical to that of a previous study [

21] that such positive psychological factors had positive effects on school life.

Male student-athletes scored higher in TRE and SRU, whereas female athletes performed better in SCL and SRE. This gender difference may be based on endocrinological factors [

30], with hormone secretion increasing under greater physical activity [

31]. Regardless of the mechanism, we can conclude that boys are better at adjusting to rules and the regimented elements of school life, while girls are better at adjusting to classes and social relationships with their peers. This observation in female student-athletes corroborates results indicating that they have higher academic success [

32]. However, this is coupled with lower athletic identity than boys, perhaps explaining why girls abandon sports at a 13.4% higher rate than abandonment rates among boys [

33].

Based on these results, we recommend that parents and other mentors highlight the excellent performance of student-athletes to the students themselves. Understanding their own achievement should lead to the formation of beneficial relationships with authority figures, including teachers. A previous study found that female student-athletes with higher HP scores are likely to have better peer relationships, similar to a study on health concerns of middle school girls [

34]. Notably, female students are more likely to discuss physical health concerns such as menstruation with their friends than their parents or managers [

35,

36,

37]. Therefore, it may be particularly important for female students to have opportunities for peer engagement on health matters, in addition to counseling with their managers. Here, we also demonstrated that PA and HP affected school adjustment among female student-athletes more than SCO, perhaps because parents of girls are more concerned about their children’s well-being than higher performance [

38].

Student-athletes who have not won awards exhibit a positive correlation between higher PA and most school-adjustment variables (excluding SRE). In contrast, among students who have won awards, higher SCO is associated with SCL and TRE. These results are consistent with previous research [

39] showing that people tend to continue participating in activities that produce satisfactory outcomes. Through winning awards, the student-athletes consider themselves competent in sports, and this feeling of achievement appears to benefit their school adjustment. Therefore, we recommend encouraging appreciation of physical activity rather than sporting competence among students without award-winning experience, especially because steady exercise is rewarding even without a physical token of victory [

40]. Our suggestion finds support in data showing that participation rates increase with greater awareness of physical activity’s benefits [

41]. Mentors of student-athletes should aim to increase successful school adjustment through providing emphasizing such benefits, rather than blaming students for lack of awards.

Despite these encouraging findings, our study has several limitations. First, participants did it voluntarily, but a sample of convenience samples was used, and the participants were limited to secondary students. Future studies should therefore investigate the observed differences among elementary, secondary, and university student-athletes. Second, because student-athletes have varied motivations [

42] that differentially influences burnout [

43], we recommend that researchers examine such motivations for engaging in sports. Third, we only examined the potential mediating influence of two variables: sex and award-winning career. Future studies should also examine factors such as sporting-event types and player careers [

44] to obtain a better understanding of factors that affect the academic achievement of student-athletes.