Perceived Competence, Achievement Goals, and Return-To-Sport Outcomes: A Mediation Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Achievement Goal Theory—Return to Sport Following Injury

1.2. Achievement Goals in Sport—Consequences and Antecedents

1.3. The 3 × 2 Conceptual Model of Achievement Goals

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Competence

2.2.2. Achievement Goals

2.2.3. Return to Sport Outcomes

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Processing and Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

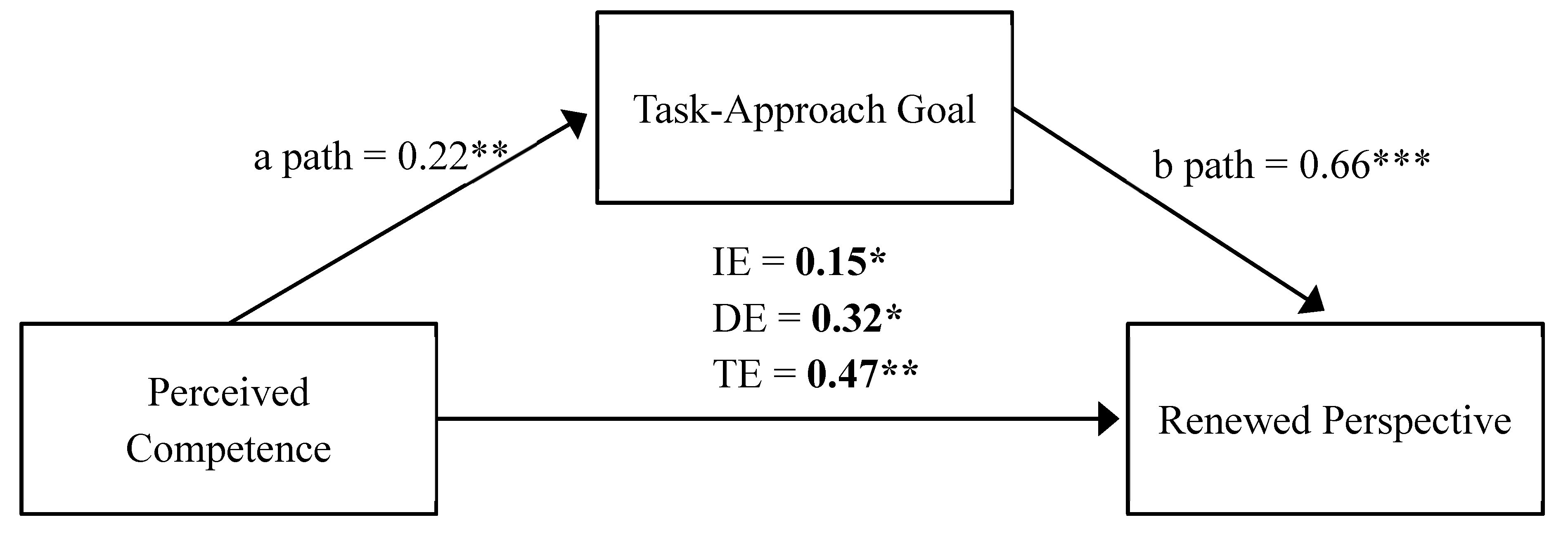

3.2. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bianco, T. Social support and recovery from sport injury: Elite skiers share their experiences. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2001, 72, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.H.; Carroll, D. The Context of Emotional Responses to Athletic Injury: A Qualitative analysispdf. J. Sport Rehabil. 1998, 7, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Dimmock, J.; Miller, J. A review of return to sport concerns following injury rehabilitation: Practitioner strategies for enhancing recovery outcomes. Phys. Ther. Sport 2011, 12, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadey, R.; Evans, L.; Hanton, S.; Neil, R. An examination of hardiness throughout the sport-injury process: A qualitative follow-up study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 872–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardern, C.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A.; Webster, K.E. A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Eklund, R.C. A longitudinal investigation of competitive athletes’ return to sport following serious injury. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2006, 18, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.; Thatcher, J.; Lavallee, D. A preliminary development of the Re-Injury Anxiety Inventory (RIAI). Phys. Ther. Sport 2010, 11, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddock-Hudson, M.; O’Halloran, P.; Murphy, G. Exploring Psychological Reactions to Injury in the Australian Football League (AFL). J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2012, 24, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Eklund, R.C.; Johnson, U.; Ivarsson, A. Psychosocial considerations of return to sport following Injury. In Psychological Bases of Sport Injuries, 4th ed.; Johnson, U., Ivarsson, A., Eds.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Podlog, L.; Eklund, R.C. Return to Sport after Serious Injury: A Retrospective Examination of Motivation and Psychological Outcomes. J. Sport Rehabil. 2005, 14, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wadey, R.; Podlog, L.; Hall, M.; Hamson-Utley, J.; Hicks-Little, C.; Hammer, C. Reinjury anxiety, coping, and return-to-sport outcomes: A multiple mediation analysis. Rehabil. Psychol. 2014, 59, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Lochbaum, M.; Stevens, T. Need satisfaction, well-being, and perceived return-to-sport outcomes among injured athletes. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2010, 22, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, C. The Relationship between Social Support and Fear of Reinjury in Recovering Female Collegiate Athletes. Ph.D. Thesis, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA, 2019. Available online: http://ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/docview/2305851155?accountid=14677 (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Ardern, C.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A.; Webster, K.E. Fear of re-injury in people who have returned to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardern, C.L.; Kvist, J.; Webster, K.E. Psychological Aspects of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. Oper. Tech. Sports Med. 2016, 24, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conti, C.; di Fronso, S.; Robazza, C.; Bertollo, M. The Injury-Psychological Readiness to return to sport (I-PRRS) scale and the Sport Confidence Inventory (SCI): A cross-cultural validation. Phys. Ther. Sport 2019, 40, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-J.; Meierbachtol, A.; George, S.Z.; Chmielewski, T.L. Fear of Reinjury in Athletes. Sports Health 2017, 9, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papadopoulos, S.; Tishukov, M. Fear of re-injury following ACL reconstruction: An overview. J. Res. Pract. Musculoskelet. Syst. 2018, 2, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Eklund, R.C. The psychosocial aspects of a return to sport following serious injury: A review of the literature from a self-determination perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 535–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Church, M.A. A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Conroy, D.E. Beyond the dichotomous model of achievement goals in sport and exercise psychology. Sport Exerc. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 1, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, A.J.; Covington, M.V. Approach and avoidance motivation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Gottardy, J. A meta-analytic review of the approach-avoidance achievement goals and performance relationships in the sport psychology literature. J. Sport Heal. Sci. 2015, 4, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lochbaum, M.; Zanatta, T.; Kazak, Z. The 2 × 2 Achievement Goals in Sport and Physical Activity Contexts: A Meta-Analytic Test of Context, Gender, Culture, and Socioeconomic Status Differences and Analysis of Motivations, Regulations, Affect, Effort, and Physical Activity Correlates. Eur. J. Investig. Heal. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 10, 173–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliot, A.J.; Murayama, K.; Pekrun, R. A 3 × 2 achievement goal model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 103, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaakkola, T.; Ntoumanis, N.; Liukkonen, J. Motivational climate, goal orientation, perceived sport ability, and enjoyment within Finnish junior ice hockey players. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nicholls, A.R.; Perry, J.L.; Calmeiro, L. Precompetitive achievement goals, stress appraisals, emotions, and coping among athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 36, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.H.; Chi, L.; Yeh, S.R.; Guo, K.B.; Ou, C.T.; Kao, C.C. Prediction of intrinsic motivation and sports performance using the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Psychol. Rep. 2011, 108, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Smith, C. Making the cut and winning a golf putting championship: The role of approach-avoidance achievement goals. Int. J. Golf Sci. 2015, 4, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; McGregor, H.A. A 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D.E.; Kaye, M.P.; Coatsworth, J.D. Coaching climates and the destructive effects of mastery-avoidance achievement goals on situational motivation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoard-Gautheur, S.; Guillet-Descas, E.; Duda, J.L. How to achieve in elite training centers without burning out? An achievement goal theory perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stenling, A.; Hassmén, P.; Holmström, S. Implicit beliefs of ability, approach-avoidance goals and cognitive anxiety among team sport athletes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schantz, L.H.; Conroy, D.E. Achievement motivation and intraindividual affective variability during competence pursuits: A round of golf as a multilevel data structure. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkalp, Z.K. Achievement goals and physical self-perceptions of adolescent athletes. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2012, 40, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, J.W.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Achievement goals, competition appraisals, and the psychological and emotional welfare of sport participants. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 302–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Morris, R.L.; Ring, C. The effects of achievement goals on performance, enjoyment, and practice of a novel motor task. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Stoll, O.; Pescheck, E.; Otto, K. Perfectionism and achievement goals in athletes: Relations with approach and avoidance orientations in mastery and performance goals. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Smith, A.L. Achievement goals, self-handicapping, and performance: A 2 × 2 achievement goal perspective. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 1471–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nien, C.L.; Duda, J.L. Antecedents and consequences of approach and avoidance achievement goals: A test of gender invariance. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 352–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cury, F.; Da Fonséca, D.; Rufo, M. Perceptions of competence, implicit theory of ability, perception of motivational climate, and achievement goals: A test of the trichotomous conceptualization of endorsement of achievement motivation in the physical education setting. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2002, 95, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J. Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 34, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.L.; Kavussanu, M. Antecedents of approach-avoidance goals in sport. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenz, R.C.; Zusho, A. Competitive swimmers’ perception of motivational climate and their personal achievement goals. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2011, 6, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D.E.; Elliot, A.J. Fear of failure and achievement goals in sport: Addressing the issue of the chicken and the egg. Anxiety. Stress. Coping 2004, 17, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascret, N.; Elliot, A.J.; Cury, F. Extending the 3 × 2 achievement goal model to the sport domain: The 3 × 2 achievement goal questionnaire for sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 17, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Taylor, J.; Cao, L. The 3 × 2 Achievement Goal Model in Predicting Online Student Test Anxiety and Help-Seeking. Int. J. E Learn. Distance Educ. 2016, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brondino, M.; Raccanello, D.; Pasini, M. Achievement goals as antecedents of achievement emotions: The 3 × 2 achievement goal model as a framework for learning environments design. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2014, 292, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.L.; Kestler, J.L. Achievement goals of traditional and nontraditional aged college students: Using the 3 × 2 achievement goal framework. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 61, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, E.; Blake, C.; Lonsdale, C. Systematic review of the effectiveness of interpersonal coach education interventions on athlete outcomes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lower, L.M.; Newman, T.J.; Pollard, W.S. International Journal of Sport Management, Recreation & Tourism Examination of the 3 × 2 Achievement Goal Model in Recreational Sport: Associations with Perceived Benefits of Sport Participation. Int. J. Sport Manag. Recreat. Tour. 2016, 26, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driediger, M.; Hall, C.; Callow, N. Imagery use by injured athletes: A qualitative analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Eklund, R.C. High-level athletes’ perceptions of success in returning to sport following injury. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.D.; Duncan, T.; Tammen, V.V. Psychometric properties of the intrinsic motivation inventoiy in a competitive sport setting: A confirmatory factor analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1989, 60, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, M.; Gauvreau, K. Principles of Biostatistics, 2nd ed.; Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fritz, M.S.; Mackinnon, D.P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kenny, D.A. MedPower: An Interactive Tool for the Estimation of Power in Tests of Mediation. 2017. Available online: https://davidakenny.shinyapps.io/MedPower/ (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Hayes, A.F. An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weissensteiner, J.R.; Abernethy, B.; Farrow, D.; Gross, J. Distinguishing psychological characteristics of expert cricket batsmen. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucciardi, D.F. Mental toughness profiles and their relations with achievement goals and sport motivation in adolescent Australian footballers. J. Sports Sci. 2010, 28, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadey, R.; Podlog, L.; Galli, N.; Mellalieu, S.D. Stress-related growth following sport injury: Examining the applicability of the organismic valuing theory. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adie, J.W.; Jowett, S. Meta-perceptions of the coach-athlete relationship, achievement goals, and intrinsic motivation among sport participants. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2750–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, J.; Sarrazin, P.; Southon, J.; Boiché, J. Psychological Characteristics and their Relation to Performance in Professional Golfers. Sport Psychol. 2009, 23, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoeber, J.; Crombie, R. Achievement goals and championship performance: Predicting absolute performance and qualification success. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Yperen, N.W.; Blaga, M.; Postmes, T. A meta-analysis of self-reported achievement goals and nonself-report performance across three achievement domains (work, sports, and education). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fawver, B.; Beatty, G.F.; Mann, D.T.Y.; Janelle, C.M.; Hodges, N.J.; Williams, A.M. Staying cool under pressure: Developing and maintaining emotional expertise in sport. In Skill Acquisition in Sport: Research, Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Hodges, N.J., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L.; Hardy, L. Injury rehabilitation: A goal-setting intervention study. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2002, 73, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, M.; Hall, C.; Forwell, L. Self-Efficacy, Imagery Use, and Adherence to Rehabilitation by Injured Athletes. J. Sport Rehabil. 2005, 14, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadey, R.; Evans, L.; Evans, K.; Mitchell, I. Perceived benefits following sport injury: A qualitative examination of their antecedents and underlying mechanisms. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2011, 23, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feise, R.J. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2002, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | M | SD | Observed Range | Cronbach’s α | r | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||

| 1. Perceived competence | 3.38 | 0.77 | 1.80–5.00 | 0.78 | --- | |||||||

| 2. Task-approach goals | 6.22 | 0.55 | 5.00–7.00 | 0.76 | 0.30 ** | --- | ||||||

| 3. Task-avoidance goals | 5.71 | 1.37 | 1.33–7.00 | 0.92 | 0.14 | 0.31 ** | --- | |||||

| 4. Self-approach goals | 5.28 | 1.18 | 2.00–7.00 | 0.77 | 0.14 | 0.45 ** | 0.19 | --- | ||||

| 5. Self-avoidance goals | 5.42 | 1.27 | 1.00–7.00 | 0.75 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.67 ** | 0.36 ** | --- | |||

| 6. Other-approach goals | 5.31 | 1.27 | 1.00–7.00 | 0.86 | 0.13 | 0.39 ** | 0.24 * | 0.45 ** | 0.43 ** | --- | ||

| 7. Other-avoidance goals | 5.08 | 1.43 | 1.00–7.00 | 0.84 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.72 ** | 0.18 | 0.74 ** | 0.44 ** | --- | |

| 8. Return concerns | 4.13 | 1.52 | 1.00–6.50 | 0.92 | −0.54 ** | −0.22 * | 0.11 | −0.08 | −0.09 | −0.24 * | 0.04 | --- |

| 9. Renewed perspective | 5.20 | 1.01 | 2.40–7.00 | 0.71 | 0.36 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.28 * | −0.02 | −0.39 ** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Astous, E.; Podlog, L.; Burns, R.; Newton, M.; Fawver, B. Perceived Competence, Achievement Goals, and Return-To-Sport Outcomes: A Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17092980

D’Astous E, Podlog L, Burns R, Newton M, Fawver B. Perceived Competence, Achievement Goals, and Return-To-Sport Outcomes: A Mediation Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(9):2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17092980

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Astous, Elyse, Leslie Podlog, Ryan Burns, Maria Newton, and Bradley Fawver. 2020. "Perceived Competence, Achievement Goals, and Return-To-Sport Outcomes: A Mediation Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 9: 2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17092980

APA StyleD’Astous, E., Podlog, L., Burns, R., Newton, M., & Fawver, B. (2020). Perceived Competence, Achievement Goals, and Return-To-Sport Outcomes: A Mediation Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 2980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17092980