Environmental Aesthetic Value Influences the Intention for Moral Behavior: Changes in Behavioral Moral Judgment

Abstract

1. Introduction

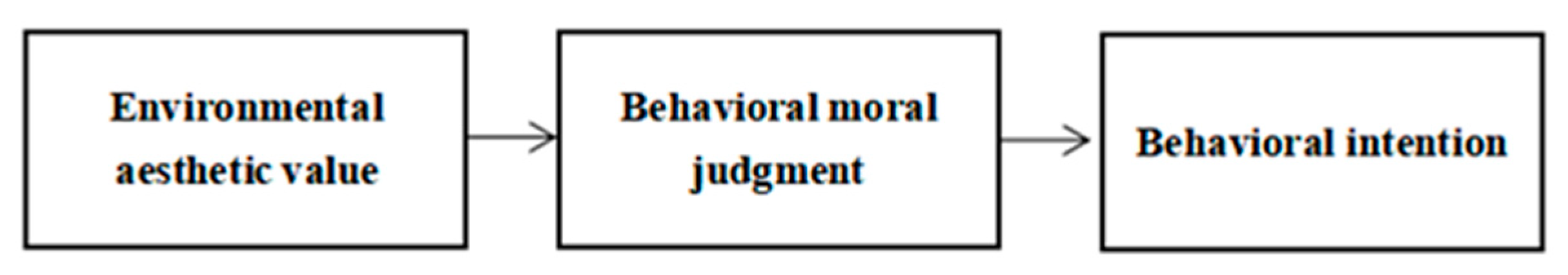

The Present Research

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Experiment 1a

2.1.1. Method

Design

Participants

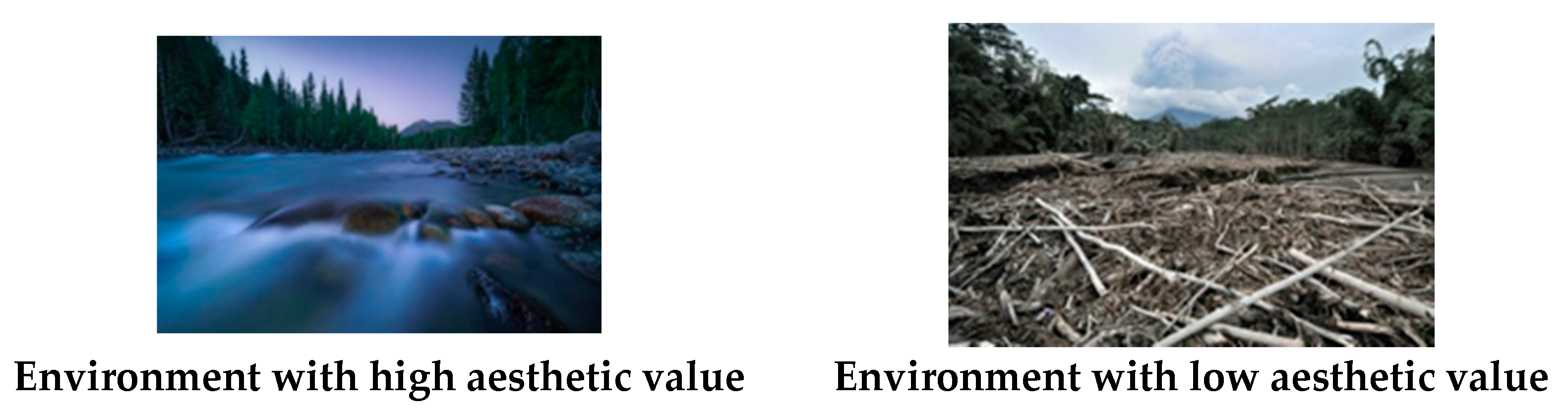

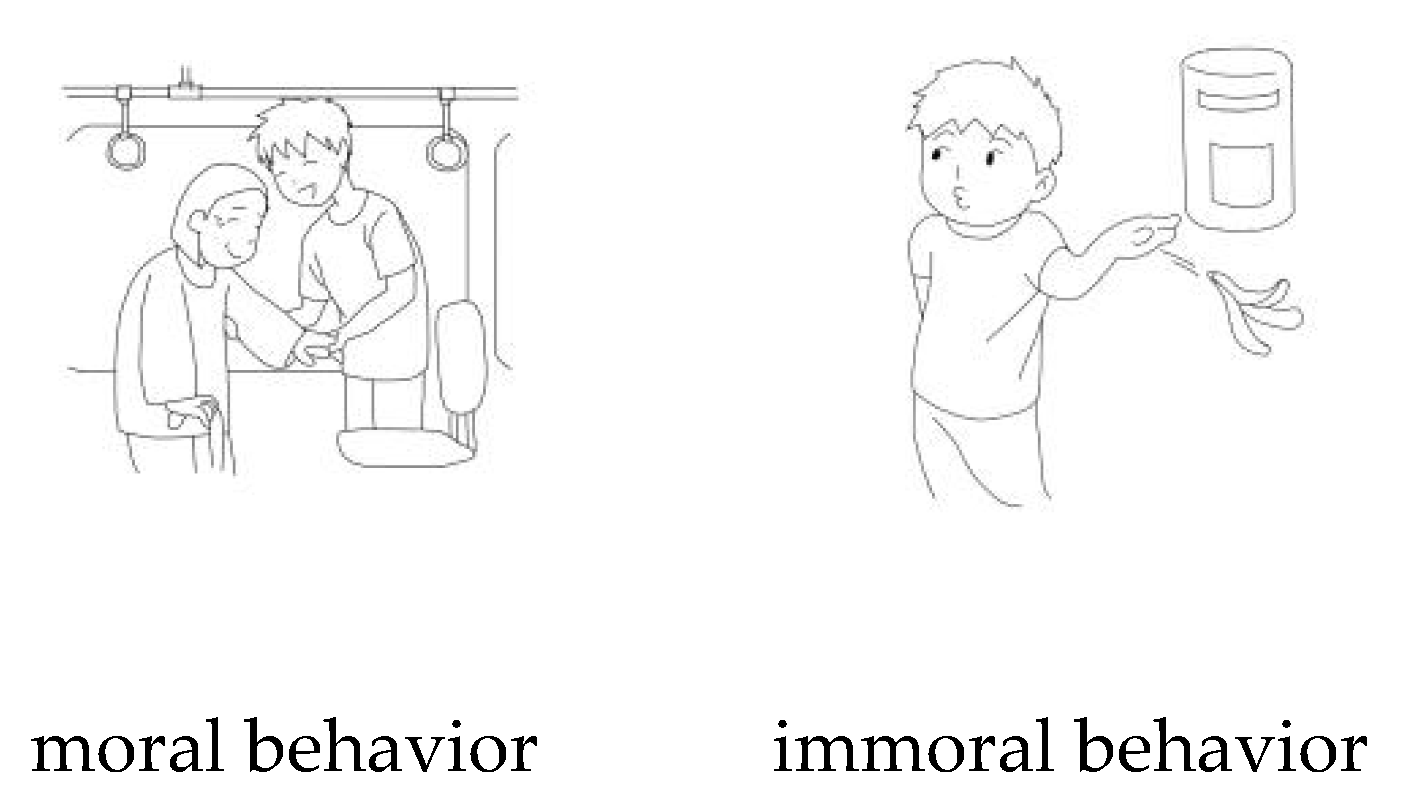

Materials

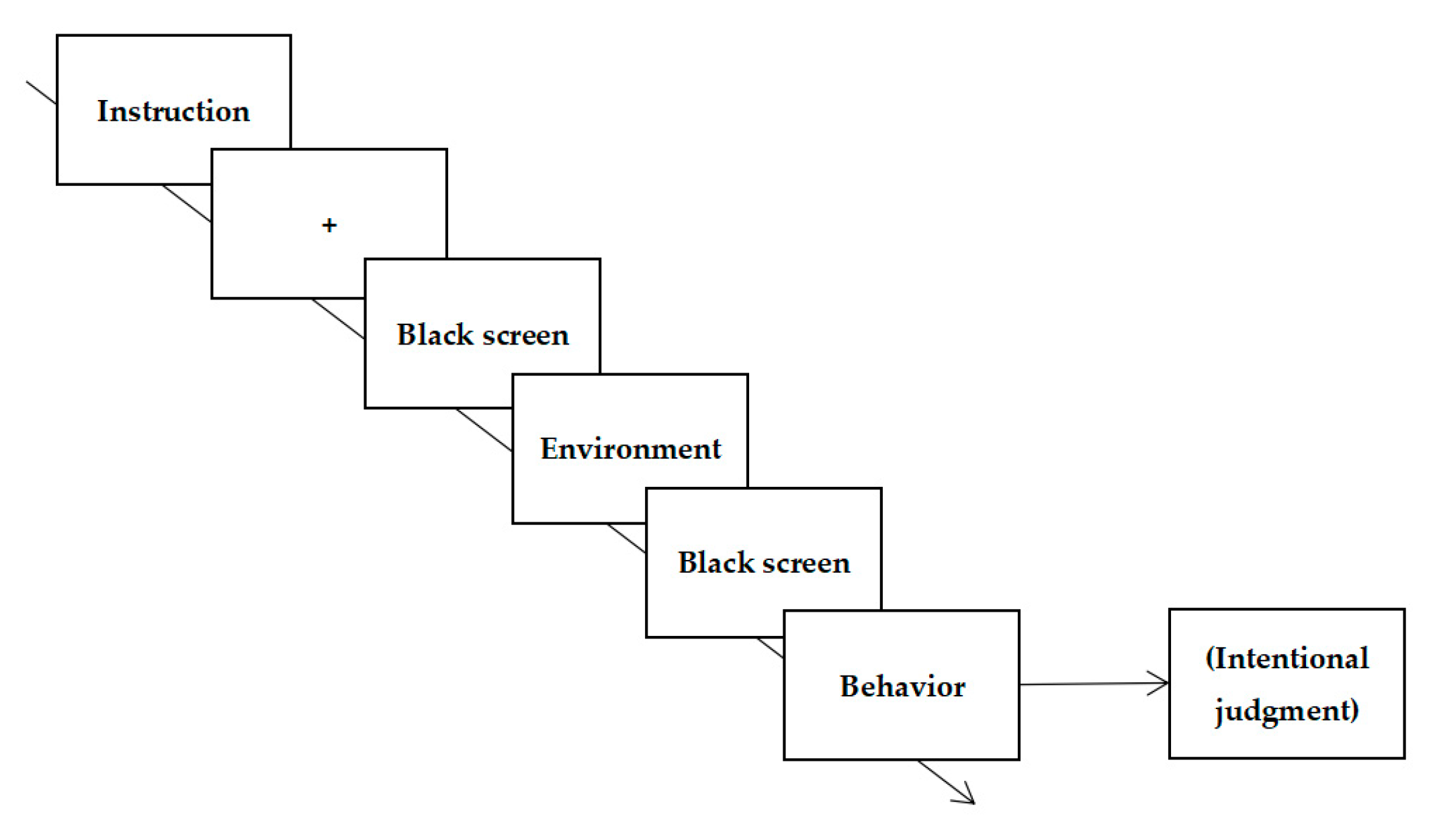

Procedure

2.1.2. Results and Discussion

2.2. Experiment 1b

2.2.1. Method

Participants

Materials

Procedure

2.2.2. Results and Discussion

Data Reduction

IAT Effect

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Experiment 2a

3.1.1. Method

Design

Participants

Materials

Procedure

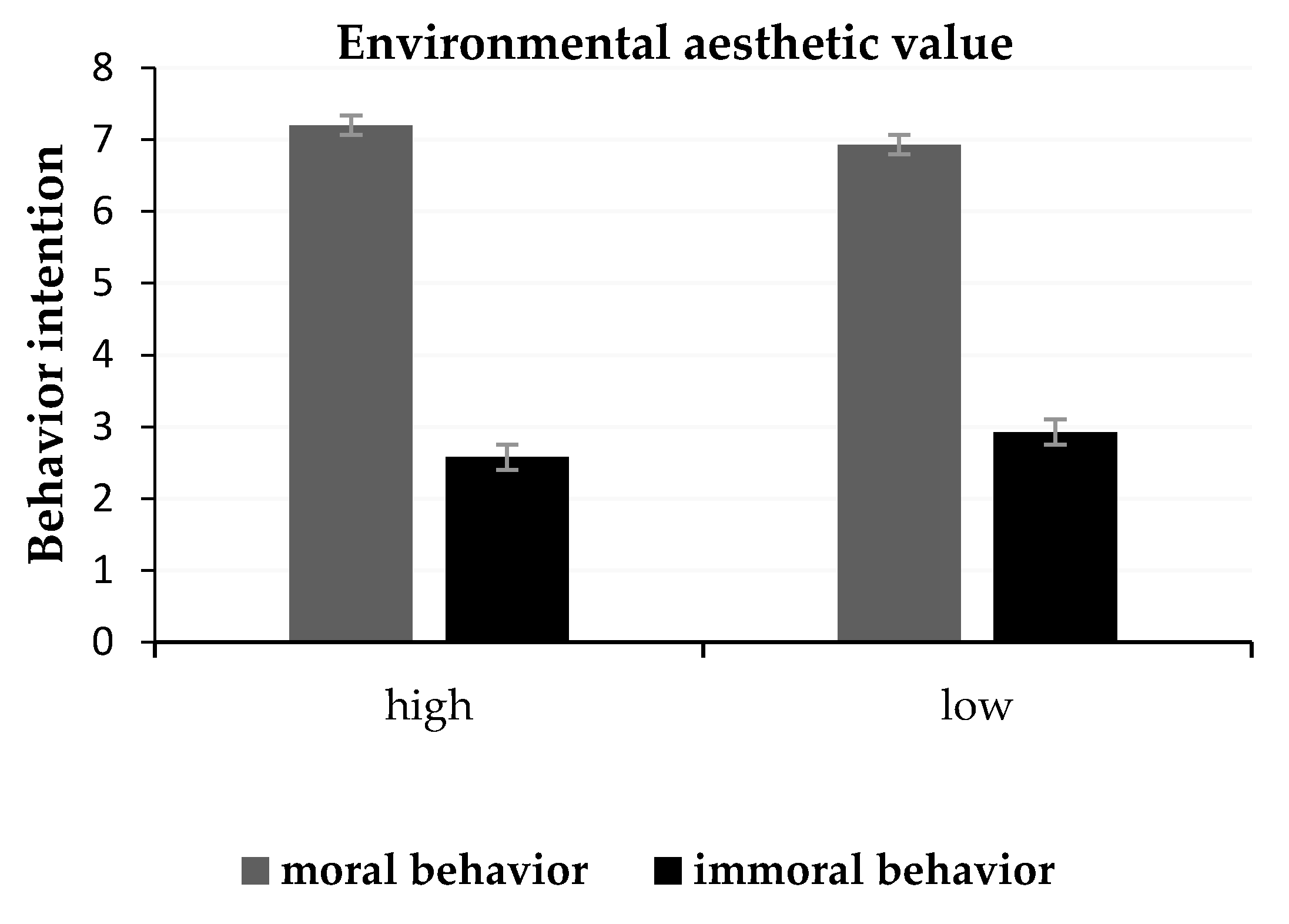

3.1.2. Results and Discussion

Regression Relation Testing

3.2. Experiment 2b

3.2.1. Method

Design

Participants

Materials

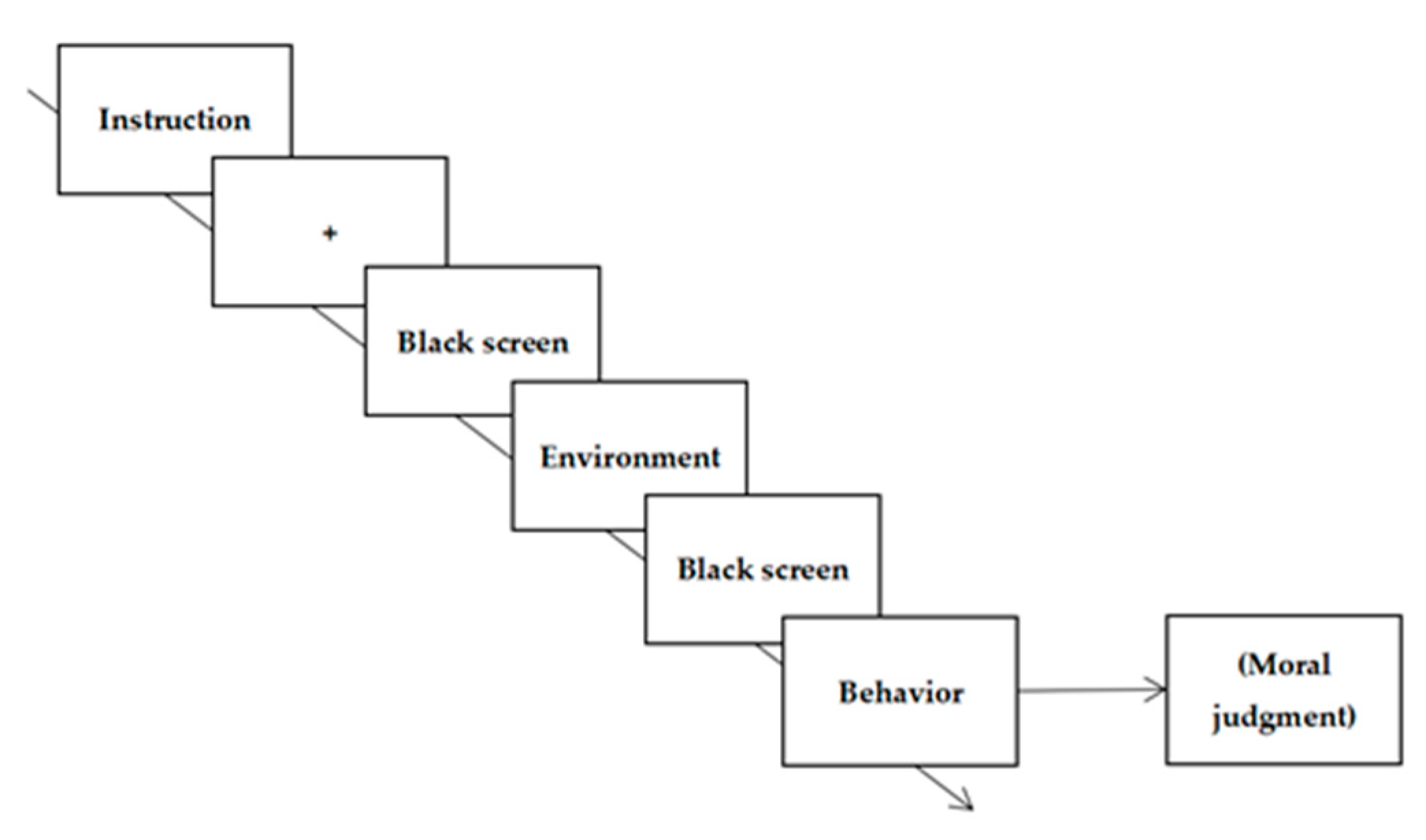

Procedure

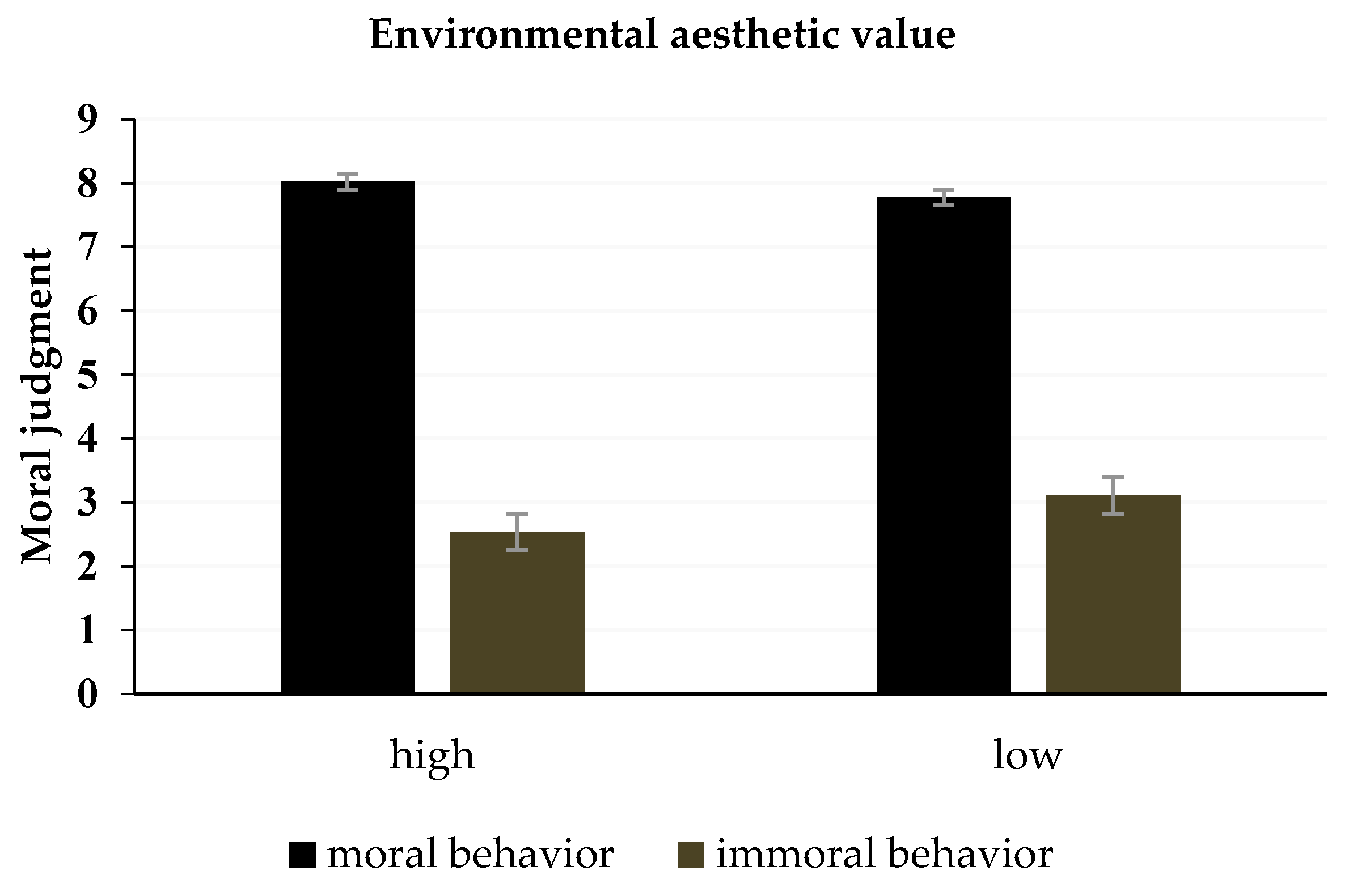

3.2.2. Results and Discussion

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keizer, K.; Lindenberg, S.; Steg, L. The Spreading of Disorder. Science 2008, 322, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime? Acoust. Speech Signal Process. Newsl. 2001, 33, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Teng, F. Air Pollution Predicts Harsh Moral Judgment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. The restorative outcomes of forest school and conventional school in young people with good and poor behaviour. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Przybylski, A.K.; Ryan, R.M. Can Nature Make Us More Caring? Effects of Immersion in Nature on Intrinsic Aspirations and Generosity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljenquist, K.; Zhong, C.-B.; Galinsky, A.D. The Smell of Virtue. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The Nature Relatedness Scale. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelling, G.L.; Coles, C.M. Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities; Touchstone: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C.B.; Bohns, V.K.; Gino, F. Good lamps are the best police: Darkness increases dishonesty and self-interested behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.J.; Zhao, L.L. Integrating aesthetics with cognitive psychology: Review on aesthetic cognition. J. Jiangnan Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2012, 5, 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, N.; Amir, O.; Ariely, D. The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept Maintenance. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Piff, P.K.; Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Keltner, D. An occasion for unselfing: Beautiful nature leads to prosociality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analytic Review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, R.; Street, M.D.; Haines, D. The Influence of Perceived Importance of an Ethical Issue on Moral Judgment, Moral Obligation, and Moral Intent. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 81, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J.R. Research on Moral Development: Implications for Training Counseling Psychologists. Couns. Psychol. 1984, 12, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Fu, X.L.; Wang, X.C. The role of moral intensity in moral decision-making in the business context. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 31, 479–482. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, T. Dimensions of Moral Intensity and Ethical Decision Making: An Empirical Study. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 1038–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Moral decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Sanders, G. Considerations in moral decision making and software piracy. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, C.; Kouchaki, M.; Gino, F. Many others are doing it, so why shouldn’t i?: How being in larger competitions leads to more cheating. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2021, 164, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, G.; Lv, F.; Sheng, C.; Shi, X. Effect of workplace environment cleanliness on judgment of counterproductive work behavior. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2017, 45, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W. Seeing Disorder: Neighborhood Stigma and the Social Construction of “Broken Windows”. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2004, 67, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnall, S.; Haidt, J.; Clore, G.L.; Jordan, A.H. Disgust as Embodied Moral Judgment. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.-B.; Liljenquist, K. Washing Away Your Sins: Threatened Morality and Physical Cleansing. Science 2006, 313, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inbar, Y.; Pizarro, D.A.; Bloom, P. Disgusting smells cause decreased liking of gay men. Emotion 2012, 12, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, Y.; Pizarro, D.A.; Knobe, J.; Bloom, P. Disgust sensitivity predicts intuitive disapproval of gays. Emotion 2009, 9, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, G. Further Consideration of the “What is Good is Beautiful” Finding. Soc. Psychol. 1978, 41, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Halit, H.; De Haan, M.; Johnson, M.H. Modulation of event-related potentials by prototypical and atypical faces. NeuroReport 2000, 11, 1871–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdesolo, P.; Desteno, D. Moral hypocrisy: Social groups and the flexibility of virtue. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 689–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohminger, N.; Lewis, R.L.; Meyer, D.E. Divergent effects of different positive emotions on moral judgment. Cognition 2011, 119, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Who is more utilitarian? Negative affect mediates the relation between control deprivation and moral judgment. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnall, S.; Benton, J.; Harvey, S. With a Clean Conscience. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1219–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, C.D.; Thompson, E.R.; Chen, H. Moral hypocrisy: Addressing some alternatives. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, E.; Ruttan, R.L. Effects of Anger, Guilt, and Envy on Moral Hypocrisy. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 38, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustichini, A.; Villeval, M.C. Moral hypocrisy, power and social preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2014, 107, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Nosek, B.A.; Banaji, M.R. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noval, L.J.; Günter, K.S.; Zhong, C.B. The positive role of negative emotions in ethical decision making. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 5 August 2014; p. 14170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Cameron, E.; Pasternack, J.; Tryon, K. Behavioral and Sociocognitive Correlates of Ratings of Prosocial Behavior and Sociometric Status. J. Genet. Psychol. 1988, 149, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Posada, C.V.; Vargas-Trujillo, E. Moral Reasoning and Personal Behavior: A Meta-Analytical Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2015, 19, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Kross, E.; Krpan, K.M.; Askren, M.K.; Burson, A.; Deldin, P.J.; Kaplan, S.; Sherdell, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, T.; Haidt, J. Hypnotic Disgust Makes Moral Judgments More Severe. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessner, R. Magnificent Moral Beauty: The Trait of Engagement with Moral Beauty. In Understanding the Beauty Appreciation Trait; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Isen, A.M.; Johnson, M.M.S.; Mertz, E.; Robinson, G.F. The influence of positive affect on the unusualness of word associations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Branigan, C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isen, A.M.; Daubman, K.A. The influence of affect on categorization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 1206–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, B.E.; Isen, A.M. The Influence of Positive Affect on Variety Seeking Among Safe, Enjoyable Products. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskine, K.J.; Kacinik, N.A.; Prinz, J.J. A Bad Taste in the Mouth. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Moncayo, L.; Reinoso-Carvalho, F.; Velasco, C. The effects of noise control in coffee tasting experiences. Food Qual. Preference 2020, 86, 104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, M.; Zellner, D.; Cogan, E.; Parker, S. Attractiveness Difference Magnitude Affected by Context, Range, and Categorization. Percept. 2014, 43, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parducci, A. Range-frequency compromise in judgment. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1963, 77, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parducci, A. The Relativism of Absolute Judgments. Sci. Am. 1968, 219, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Parker, M.S. Categorization reduces the effect of context on hedonic preference. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2009, 71, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zellner, D.A.; Kern, B.B.; Parker, S. Protection for the good: Subcategorization reduces hedonic contrast. Appetite 2002, 38, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arielli, E. Contrast and Assimilation in Aesthetic Judgments of Visual Artworks. Empir. Stud. Arts 2012, 30, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussweiler, T. Comparison processes in social judgment: Mechanisms and consequences. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherif, M.; Taub, D.; Hovland, C.I. Assimilation and contrast effects of anchoring stimuli on judgments. J. Exp. Psychol. 1958, 55, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, E.; Parker, S.; Zellner, D.A. Beauty beyond compare: Effects of context extremity and categorization on hedonic contrast. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2013, 39, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolese, M.J.; Zellner, D.A.; Vasserman, M.; Parker, S. Categorization affects hedonic contrast in the visual arts. Bull. Psychol. Arts 2005, 5, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant, C.; Bodner, G.E. Context effects on beauty ratings of photos: Building contrast effects that erode but cannot be knocked down. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapel, D.A.; Koomen, W. I, we, and the effects of others on me: How self-construal level moderates social comparison effects. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Yu, M.; Li, Y.; Mo, L. The neural correlates of integrated aesthetics between moral and facial beauty. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.C. Environmental Psychology: Mind, Behavior, and Environment; Shanghai Educational Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kotabe, H.P.; Kardan, O.; Berman, M.G. The order of disorder: Deconstructing visual disorder and its effect on rule-breaking. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2016, 145, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Moral Style | The Attributes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Morality | Artistry | Complexity | |

| Moral | 6.02 ± 0.74 | 4.43 ± 0.79 | 3.98 ± 0.99 |

| immoral | 2.05 ± 0.53 | 4.18 ± 0.40 | 3.88 ± 0.44 |

| P | <0.001 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| Behavior | Environmental Aesthetic Value | The Score of Behavioral Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | ||

| Moral | High | 7.20 | 0.87 |

| Moral | Low | 6.93 | 0.93 |

| Immoral | High | 2.58 | 0.82 |

| Immoral | Low | 2.93 | 0.64 |

| Task | “E” Key | “I” Key |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | High aesthetic value | Low aesthetic value |

| 2 | Moral | Immoral |

| 3 | High/Moral | Low/Immoral |

| 4 | High/Moral | Low/Immoral |

| 5 | Immoral | Moral |

| 6 | High/Immoral | Low/Moral |

| 7 | High/Immoral | Low/Moral |

| Style | ACC | RT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Compatibility | 0.98 | 0.021 | 857.15 | 234.08 |

| No-compatibility | 0.94 | 0.046 | 1586.81 | 625.90 |

| RT | ||

|---|---|---|

| M(ms) | SD | |

| Third part | 915.33 | 274.13 |

| Fourth part | 798.96 | 206.32 |

| Sixth part | 1724.93 | 685.95 |

| Seventh part | 1413.70 | 504.92 |

| The Moral Judgment of Moral Behavior | The Moral Judgment of Immoral Behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| Moral behavior intention | 0.33 ** | |

| Immoral behavior intention | 0.62 ** |

| Behavior | Environmental Aesthetic Value | The Indirect Moral Judgment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | ||

| Moral | High | 8.02 | 0.89 |

| Moral | Low | 7.78 | 0.89 |

| immoral | High | 2.54 | 0.77 |

| immoral | Low | 3.11 | 0.59 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, C.; He, X. Environmental Aesthetic Value Influences the Intention for Moral Behavior: Changes in Behavioral Moral Judgment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126477

Wu C, He X. Environmental Aesthetic Value Influences the Intention for Moral Behavior: Changes in Behavioral Moral Judgment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126477

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Chenjing, and Xianyou He. 2021. "Environmental Aesthetic Value Influences the Intention for Moral Behavior: Changes in Behavioral Moral Judgment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126477

APA StyleWu, C., & He, X. (2021). Environmental Aesthetic Value Influences the Intention for Moral Behavior: Changes in Behavioral Moral Judgment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126477