Music Is Life—Follow-Up Qualitative Study on Parental Experiences of Creative Music Therapy in the Neonatal Period

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample and Interview Characteristics

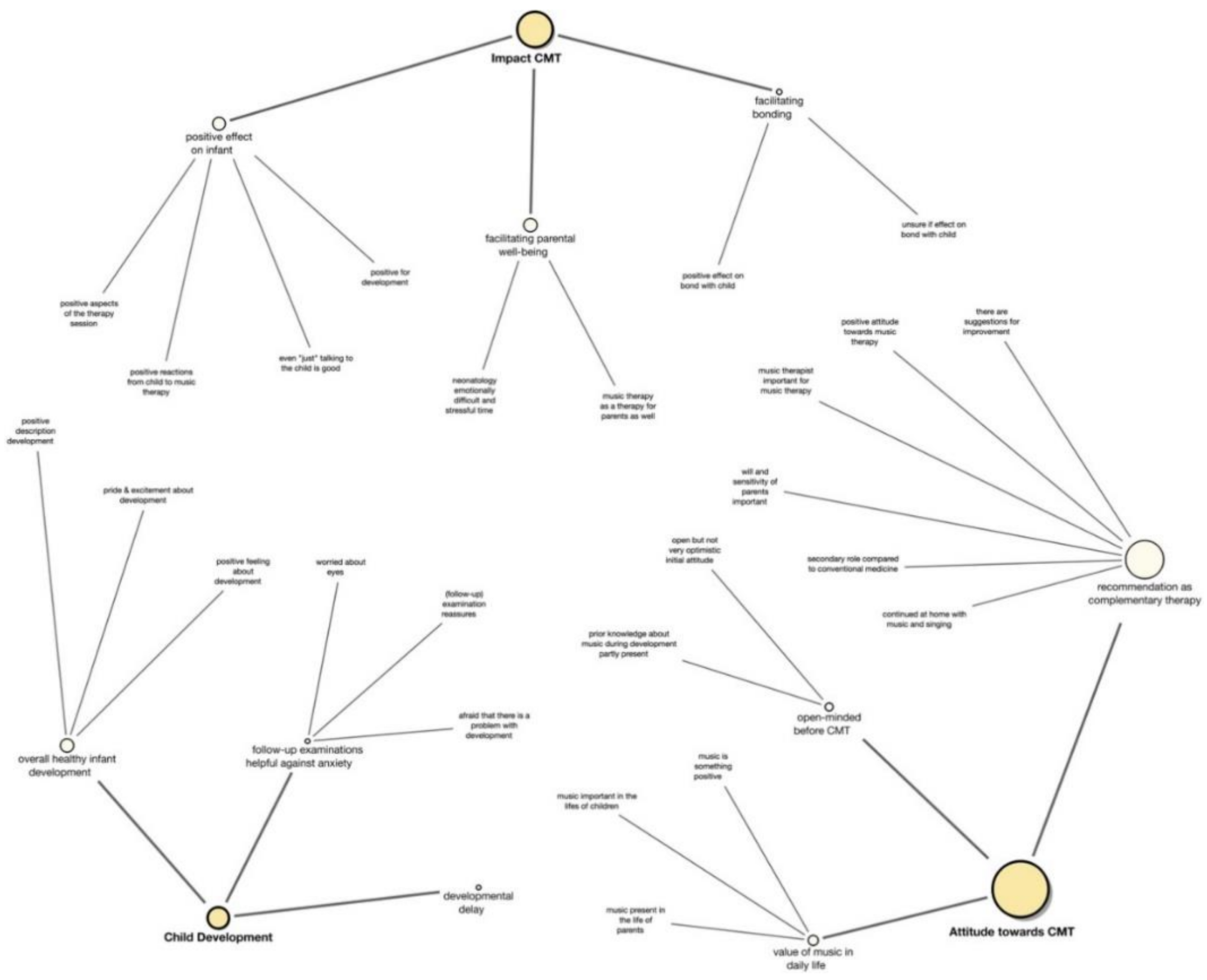

3.2. Findings

- Impact CMT: (a) positive effect on infant (b) facilitating parental wellbeing (c) facilitating bonding

- Attitude toward CMT: (a) open-minded before CMT (b) value of music in daily life (c) recommendation as a complementary therapy

- Child development: (a) developmental delay (b) follow-up examinations helpful against anxiety (c) overall healthy infant development

3.2.1. Impact of Creative Music Therapy: (a) Positive Effect on Infant (b) Facilitating Parental Relaxation and Well-Being (c) Facilitating Bonding

That the children were much calmer every time during music therapy. (I: Yes) They were much calmer during music therapy, afterward, and also when you had them outside or talked to them.(5M, 7)

… and also every reaction from L. [name of infant]. The smallest grin, I would say, or eye movements or whatever.(3F (M), 10)

Maybe the child knew that it wasn’t alone and someone was there for it.(5M, 43)

And that was nice for me too—to know that even when I’m not there, he also has music therapy and he gets, uh, something.(1M, 17)

And with the music therapy, I think he has learned that people who engage positively with him, that he can also trust them. So, I think his basic trust is greater than that of a child who was born at term and only trusts his own mother.(1M, 17)

I think she enjoyed it, she still really likes music. Thus, I think whenever there’s music she likes it.(4M, 46)

Just as I said, that was a (really medical?) but also the soul somehow, the whole thing and also the reactions of L. [name of infant] and also our own, we were surprised.(3F (M), 54)

… And in that sense, it [CMT] is also something that takes the stress away from you. (I: Ok) So you are often in fear and stressed and worried and so on and this music therapy, I think, is not just one for the child, but also one for the parents, who commit to it.(1M, 29)

For me, it was also very emotional yes. … I cried a lot, of course, also during this music therapy … you are calmed down with this music and when the tears start to fall. So, I often cried a lot. And I found it great, of course, that I was not, always asked: “Hey, are you okay?”(6M, 69)

It always made me happy. And also satisfied, because I knew I could do something.(1M, 29)

… maybe I relaxed a bit more … I don’t know I think you’re in, you’re in such a traumatic situation so I’m not sure you can … I mean, for me it was super nice but I observed even more if she had eaten that day or if she had, if they had to intubate her again … So there were more medical impacts which had a bigger impact on if I was relaxed or not …(4M, 61–64)

And this moment of bonding, through this sharing, well, humming and breathing, attuning to the breath was a very important connection for me, which perhaps also replaces this breastfeeding a bit, which a mother normally has.(1M, 15)

It doesn’t really matter because really with the singing and humming, the parents’ voice and maybe also the oscillation, the vibrations and if the child lies on the skin, then additionally a bond will be established.(2F, 23)

3.2.2. Attitude toward CMT: (a) Open-Minded before CMT (b) Value of Music in Daily Life (c) Recommendation as a Complementary Therapy

The attitude was a bit reserved, I guess. We had our concerns, especially because of the time. And because there isn’t very much experience with this music therapy. We knew that it was something new but we didn’t expect too much, honestly. (I: Yes) In the beginning.(3F (M), 16)

I don’t see any risk with it so I think you should definitely do it.(4M, 24)

And uhm, for us that was the best decision.(6M, 111)

… that has also shown me a lot that you can actually always incorporate music into life. So we sing a lot … it’s unbelievable how much my son also sings and whenever he is stressed somehow ( ) Monday morning he has to go to school, then we start singing.(1M, 43)

And of course, she explained it to me in detail, what she did with the baby, how it affects the child, how I can also contribute myself. And that was an insanely great support that we got there…And there were just insanely great conversations with her.(1M, 13–19)

I mean I was asked, probably like all mothers, who have had a child so early [sighing] to go to the psychologist. I personally don’t think much of it. I also had a conversation with the psychologist, which for me (rather?), yes…If a lady who is quite a bit younger than me and doesn’t have a child, such a person can’t tell me or can’t [sighs] know how I feel. Nobody can.(6 M, 85)

And all these alarms through this intensive care unit …it’s incredibly stressful to hear such an alarm all the time.(1M, 13)

For me, it was all very positive (I: Ok) and you could say I, I thought it was a pity that not all children had access to the music therapy.(4M, 16)

3.2.3. Child Development: (a) Developmental Delay (b) Follow-Up Examinations Helpful against Anxiety (c) Overall Healthy Infant Development

So, has *maybe a slight concentration weakness but that’s actually only (…), not necessarily due to the premature birth I find.(3F (M), 4)

Yes, it’s like concerns. And so, it was, confirmation after this examination. Then you had like a confirmation that it works, everything is good.(3F (M), 66)

And health-wise I can say, for the fact that she was born so early. She is very rarely, very rarely ill.(6M, 19)

However, this has another level, a deeper level. Also, a thankfulness, that V. [name of infant] is healthy.(2F, 67)

So I think both must complement each other. So the purely medical measures are of course enormously important, because, the child would not be able to survive by itself. So it needs 24-h care and also that, the right devices, so that it works at all. And that is very clear. And music therapy is just more on the emotional level. So the medical that is necessary can be complemented …(1M, 25)

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of CMT

4.2. Child Development from the Parents’ Perspective

4.3. CMT Recommendation as a Complementary Therapy

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Appendix A.1. Introductory Questions

Appendix A.2. Main Questions

- What do you remember from the music therapy?

- What did you find positive and what negative about the music therapy?

- What was your attitude toward music therapy when you were first informed about it and how did that attitude develop during the therapy process?

- How would you rate music therapy in terms of benefits and risks? And in your opinion, how can this be compared with purely medical procedures?

- How did you experience your time in neonatology in general and how did you feel during and after the therapy sessions?

- How did you see your role during music therapy and did you take an active part?

- If actively involved: Did you observe anything in your child during or after music therapy?

- How would you describe the bond with your child throughout the therapy process?

- Has the bond with your child changed due to a change in its emotional state and the role taken in therapy?

- How was the interaction with the music therapist?

- What place does music have in your life?

- Had the monochord already been used for therapy at the time? If yes: How did you feel the vibrations from the monochord during kangarooing?

- What were your thoughts before the neurological follow up exams after two and five years?

- Has your child already started school? If so, how did you feel about it?

- Music therapy is offered to families with a prematurely born baby and they would like to hear your opinion about it. What would you tell them?

Appendix A.3. Final Question

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Chawanpaiboon, S.; Vogel, J.P.; Moller, A.-B.; Lumbiganon, P.; Petzold, M.; Hogan, D.; Landoulsi, S.; Jampathong, N.; Kongwattanakul, K.; Laopaiboon, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e37–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glass, H.C.; Costarino, A.T.; Stayer, S.A.; Brett, C.M.; Cladis, F.; Davis, P.J. Outcomes for Extremely Premature Infants. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 120, 1337–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaucher, Y.E.; Peralta-Carcelen, M.; Finer, N.N.; Carlo, W.A.; Gantz, M.; Walsh, M.C.; Laptook, A.R.; Yoder, B.A.; Faix, R.G.; Das, A.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in the Early CPAP and Pulse Oximetry Trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2495–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vohr, B.R.; Stephens, B.E.; Higgins, R.D.; Bann, C.; Hintz, S.R.; Das, A.; Newman, J.E.; Peralta-Carcelen, M.; Yolton, K.; Dusick, A.M.; et al. Are Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infants Improving? Impact of Bayley Assessment on Outcomes. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 222–228.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerr-Wilson, C.O.; Mackay, D.F.; Smith, G.C.S.; Pell, J. Meta-analysis of the association between preterm delivery and intelligence. J. Public Health 2012, 34, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Marlow, N. Growing up after extremely preterm birth: Lifespan mental health outcomes. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014, 19, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.; Hennessy, E.; Smith, R.; Trikic, R.; Wolke, D.; Marlow, N. Academic attainment and special educational needs in extremely preterm children at 11 years of age: The EPICure study. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009, 94, F283–F289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellier, E.; Platt, M.J.; Andersen, G.L.; Krägeloh-Mann, I.; De La Cruz, J.; Cans, C.; Network, S.O.C.P. Decreasing prevalence in cerebral palsy: A multi-site European population-based study, 1980 to 2003. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schappin, R.; Wijnroks, L.; Venema, M.M.U.; Jongmans, M.J. Rethinking Stress in Parents of Preterm Infants: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, A.T.F.; Lasiuk, G.C.; Radünz, V.; Hegadoren, K. Scoping Review of the Mental Health of Parents of Infants in the NICU. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 46, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gangi, S.; Dente, D.; Bacchio, E.; Giampietro, S.; Terrin, G.; De Curtis, M. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Parents of Premature Birth Neonates. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 82, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albersheim, S. The Extremely Preterm Infant: Ethical Considerations in Life-and-Death Decision-Making. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garel, M.; Dardennes, M.; Blondel, B. Mothers’ psychological distress 1 year after very preterm childbirth. Results of the epipage qualitative study. Child Care Health Dev. 2006, 33, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud, K.; Lee, K.J.; Doyle, L.; Anderson, P.J. Very Preterm Birth Influences Parental Mental Health and Family Outcomes Seven Years after Birth. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puthussery, S.; Chutiyami, M.; Tseng, P.-C.; Kilby, L.; Kapadia, J. Effectiveness of early intervention programs for parents of preterm infants: A meta-review of systematic reviews. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ettenberger, M. Music therapy in the neonatal intensive care unit: Putting the families at the centre of care. Br. J. Music Ther. 2017, 31, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F.; Hugoson, P. Sounding Together: Family-Centered Music Therapy as Facilitator for Parental Singing During Skin-to-Skin Contact. In Early Vocal Contact and Preterm Infant Brain Development, 1st ed.; Filippa, M., Kuhn, P., Westrup, B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ullsten, A. Family-centred music intervention—An emotional factor that modulates, modifies and alleviates infants’ pain experiences. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haslbeck, F.B.; Bassler, D. Clinical Practice Protocol of Creative Music Therapy for Preterm Infants and Their Parents in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 2020, e60412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F.B. Creative music therapy with premature infants: An analysis of video footage. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2013, 23, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F. Three little wonders. Music therapy with families in neonatal care. In Models of Music Therapy with Families; Lindahl, J.S., Thompson, G.A., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2016; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nordoff, P.; Robbins, C. Creative Music Therapy: Individualized Treatment for the Handicapped Child; John Day Company: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck, F.B.; Jakab, A.; Held, U.; Bassler, D.; Bucher, H.-U.; Hagmann, C. Creative music therapy to promote brain function and brain structure in preterm infants: A randomized controlled pilot study. NeuroImage Clin. 2020, 25, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fachner, J.; Gold, C.; Erkkilä, J. Music Therapy Modulates Fronto-Temporal Activity in Rest-EEG in Depressed Clients. Brain Topogr. 2012, 26, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelsch, S. A Neuroscientific Perspective on Music Therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1169, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehl, S.M.; La Marca-Ghaemmaghami, P.; Haller, M.; Pichler-Stachl, E.; Bucher, H.U.; Bassler, D.; Haslbeck, F.B. Creative Music Therapy with Premature Infants and Their Parents: A Mixed-Method Pilot Study on Parents’ Anxiety, Stress and Depressive Symptoms and Parent–Infant Attachment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieleninik, Ł.; Ghetti, C.; Gold, C. Music Therapy for Preterm Infants and Their Parents: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ettenberger, M.; Odell-Miller, H.; Cárdenas, C.R.; Serrano, S.T.; Parker, M.; Llanos, S.M.C. Music Therapy with Premature Infants and Their Caregivers in Colombia—A Mixed Methods Pilot Study Including a Randomized Trial. Voices World Forum Music Ther. 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, E.; Ettenberger, M. Music Therapy Self-Care Group for Parents of Preterm Infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Clinical Pilot Intervention. Medicines 2018, 5, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shoemark, H.; Grocke, D. The Markers of Interplay Between the Music Therapist and the High Risk Full Term Infant. J. Music Ther. 2010, 47, 306–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F.B.; Bucher, H.-U.; Bassler, D.; Hagmann, C. Creative music therapy to promote brain structure, function, and neurobehavioral outcomes in preterm infants: A randomized controlled pilot trial protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volpe, J.J. Neurology of the Newborn, 5th ed.; Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed-Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, LA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4129-7212-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, E.H.; Curry, L.A.; Devers, K.J. Qualitative Data Analysis for Health Services Research: Developing Taxonomy, Themes, and Theory. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joffe, H. Thematic Analysis. In Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Papoušek, M.; Papoušek, H.; Symmes, D. The meanings of melodies in motherese in tone and stress languages. Infant Behav. Dev. 1991, 14, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haslbeck, F.B. Music therapy for premature infants and their parents: An integrative review. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2012, 21, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, S.; Shoemark, H.; Črnčec, R.; Newnham, C.; Paul, C.; Prior, M.; Coward, S.; Burnham, D. Music therapy with hospitalized infants-the art and science of communicative musicality. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2012, 33, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F.B. The interactive potential of creative music therapy with premature infants and their parents: A qualitative analysis. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2013, 23, 36–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzi, A.; Meschini, R.; Medeiros, M.D.M.; Piccinini, C.A. NICU music therapy and mother-preterm infant synchrony: A longitudinal case study in the South of Brazil. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2020, 29, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemark, H. Translating “Infant-Directed Singing” into a Strategy for the Hospitalized Family. In Music Therapy and Parent-Infant Bonding; Edwards, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ghetti, C.; Bieleninik, Ł.; Hysing, M.; Kvestad, I.; Assmus, J.; Romeo, R.; Ettenberger, M.; Arnon, S.; Vederhus, B.J.; Gaden, T.S.; et al. Longitudinal Study of music Therapy’s Effectiveness for Premature infants and their caregivers (LongSTEP): Protocol for an international randomised trial. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ettenberger, M.; Odell-Miller, H.; Cárdenas, C.R.; Parker, M. Family-centred music therapy with preterm infants and their parents in the Neonatal-Intensive-Care-Unit (NICU) in Colombia: A mixed-methods study. Nord. J. Music Ther. 2016, 25, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shoemark, H.; Dahlstrøm, M.; Bedford, O.; Stewart, L. The effect of a voice-centered psycho-educational program on maternal self-efficacy: A feasibility study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Juffer, F. Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treyvaud, K.; Spittle, A.; Anderson, P.J.; O’Brien, K. A multilayered approach is needed in the NICU to support parents after the preterm birth of their infant. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 139, 104838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D. The health change trajectory model: An integrated model of health change. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 38, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, M.; Janvier, A.; Lefebvre, F.; Luu, T.M. Parental Perspectives Regarding Outcomes of Very Preterm Infants: Toward a Balanced Approach. J. Pediatr. 2018, 200, 58–63.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janvier, A.; Lantos, J.; Aschner, J.; Barrington, K.; Batton, B.; Batton, D.; Berg, S.F.; Carter, B.; Campbell, D.; Cohn, F.; et al. Stronger and More Vulnerable: A Balanced View of the Impacts of the NICU Experience on Parents. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linley, P.A.; Joseph, S. Positive Change Following Trauma and Adversity: A Review. J. Trauma. Stress 2004, 17, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.S.; Kirchner, J. Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2020, 283, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.B. Involvement of patients in Clinical Governance. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2006, 44, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.; Montori, V.M.; Godlee, F. Patients can improve healthcare: It’s time to take partnership seriously. BMJ 2013, 346, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemark, H. Time Together: A Feasible Program to Promote parent-infant Interaction in the NICU. Music Ther. Perspect. 2017, 36, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F. Wiegenlieder für die Kleinsten. In Ausgewählte Lieder von Eltern für Eltern frühgeborener Kinder; Amiamusica: Uster, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Funnel, M.M. Patient empowerment. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2004, 27, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baraldi, E.; Allodi, M.W.; Smedler, A.-C.; Westrup, B.; Löwing, K.; Ådén, U. Parents’ Experiences of the First Year at Home with an Infant Born Extremely Preterm with and without Post-Discharge Intervention: Ambivalence, Loneliness, and Relationship Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, V.C.; Steelfisher, G.K.; Salhi, C.; Shen, L.Y. Coping with the neonatal intensive care unit experience: Parents’ strategies and views of staff support. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 26, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, J.; Jones, L. Discharge and beyond. A longitudinal study comparing stress and coping in parents of preterm infants. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2010, 16, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, A.; Orton, J.; Anderson, P.J.; Boyd, R.; Doyle, L. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 11, CD005495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, N.; Gunten, G.V. Interprofessional Collaboration in a New Model of Transitional Care for Families with Preterm Infants—The Health Care Professional’ s Perspective. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslbeck, F. Responsiveness—Die zentrale musiktherapeutische Kompetenz in der Neonatologie. Musikther. Umsch. 2014, 35, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sandelowski, M. Focus on Qualitative Methods Sample Size in Qualitative Research. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondanaro, J.F.; Ettenberger, M.; Park, L. Mars Rising: Music Therapy and the Increasing Presence of Fathers in the NICU. Music Med. 2016, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants (n) | Parents (6: 4 Mothers & 2 Fathers) | Infants (7) |

|---|---|---|

| Interview partner nationality (n) | ||

| Swiss | 2 | |

| German | 1 | |

| Danish | 1 | |

| Slovenia | 1 | |

| Kosovo | 1 | |

| Interview partner educational qualification | ||

| (% (n)) | ||

| Compulsory education | 17 (1) | |

| Apprenticeship | 33 (2) | |

| University degree | 50 (3) | |

| Primigravida (% (n)) | 33 (2) | |

| Primiparous (% (n)) | 66 (4) | |

| Twins (% (n)) | 29 (2) | |

| Male infants (% (n)) | 29 (2) | |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) (median (range)) | 25.57 (24–27) | |

| Birth weight (g) (median (range)) | 854.29 (610–1070) | |

| Birth size (cm) (median (range)) | 33.43 (30–38) | |

| Apgar score (10 min) (median (range)) | 6.2857 (4–8) | |

| Chorioamnionitis (% (n)) | 42.86% (3) | |

| ROP (% (n)) | 28.57% (2) | |

| BPD (% (n)) | 14.29% (1) | |

| Intubation days (median (range)) | 5 (0–13) | |

| Cerebral haemorrhage (% (n)) | 0 (0) | |

| Ventricular dilatation (% (n)) | 0 (0) | |

| Sepsis (% (n)) | 0 (0) | |

| NEC (% (n)) | 0 (0) | |

| Day of discharge (median (range)) | 88.57 (58–117) | |

| Weight at discharge (median (range)) | 3211.43 (2540–4480) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haslbeck, F.B.; Schmidli, L.; Bucher, H.U.; Bassler, D. Music Is Life—Follow-Up Qualitative Study on Parental Experiences of Creative Music Therapy in the Neonatal Period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126678

Haslbeck FB, Schmidli L, Bucher HU, Bassler D. Music Is Life—Follow-Up Qualitative Study on Parental Experiences of Creative Music Therapy in the Neonatal Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126678

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaslbeck, Friederike Barbara, Lars Schmidli, Hans Ulrich Bucher, and Dirk Bassler. 2021. "Music Is Life—Follow-Up Qualitative Study on Parental Experiences of Creative Music Therapy in the Neonatal Period" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126678

APA StyleHaslbeck, F. B., Schmidli, L., Bucher, H. U., & Bassler, D. (2021). Music Is Life—Follow-Up Qualitative Study on Parental Experiences of Creative Music Therapy in the Neonatal Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126678