Identity (Re)Construction of Female Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Foundation

1.2. Identity Formation in Adolescence

1.3. Identity Construction and Substance Use in Adolescence

1.4. Intersectional Identity and the Stigmatization of Substance Use

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

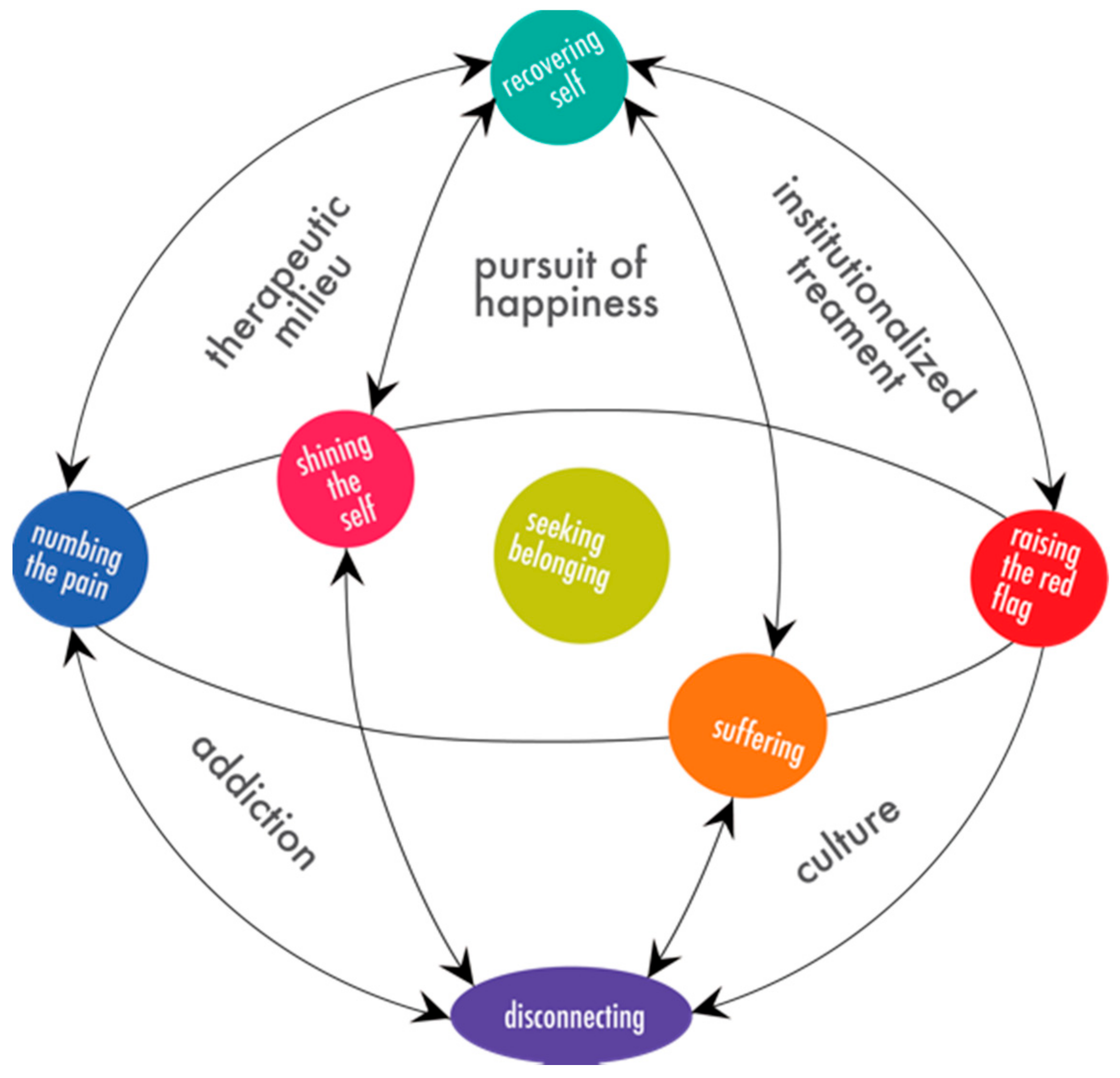

3.1. Findings of Dimensional Analysis

3.2. Findings of Situational Analysis

So, I felt like I didn’t have a right to have those emotions. I felt like because I have all these things, I’m so privileged, I have all this stuff that I didn’t have the right to feel the way I did. (Gabby, 16)

It was kind of more like the pattern from, not just my family, but the school that I was in, it was like nobody cared what you were doing or how you were doing it, so long as it looked good. (Charlotte, 16)

My other experiences with adults who—I guess I have two other experiences. Adults who work in schools, it’s their job to say that doing drugs is bad and all this stuff is bad so I don’t even know really their personal opinion. It is bad, but whether it’s something that they know it’s going to happen or I don’t know. I think that’s a problem because then who do kids go to when they need help. At least I didn’t know who I could go to about that. (Trinity, 17)

I see it in the news too like with the opioid epidemic. Just adults saying this number of people does drugs. It’s very dehumanizing. (Trinity, 17)

The government actually, they called CPS because they were like, “Her parents are neglecting her. She is going to die if she keeps doing this.” So, they were like, “Okay, we’re going to put her in this prison ward.” So, they put me there for a long time. (Lina, 15)

So, kind of just figuring out the world for myself. It was very hard working just not in the right directions. Now, it’s going to be in the right direction. (Toby, 18)

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Proposition 1: Development of the Pseudo-Identity through Substance Use Is an Adaptation to the Internal and External Environment of the Adolescent

4.2. Minor Theoretical Proposition 1: Behaviors Associated with the Pseudo-Identity Reflect the Adolescent’s View of Self

4.3. Theoretical Proposition 2: Core Cultural and Societal Positions around Treatment of Substance Use Have Direct and Indirect Effects on Well-Being and Identity Development of Adolescents

4.4. Theoretical Proposition 3: Current Modalities of Treatment and Therapy, Specifically the Prescription of 12-Step Programs, Allows Reinforcement and Attachment to False Identities

4.5. Theoretical Proposition 4: Integrative Practices Support Development of Relational Well-Being, Non-Attachment to Pseudo-Identity, and Reconnection to the Lost Pieces of the Self in Context

I think they’re the working version of my values from before. Because honestly, I think arrogance, for example, is just an extreme version of confidence. It’s just the nonworking version like before, the nonworking versions of my current values. (Cassie, 15)

When I started caring what other people thought about me was when I kind of lost a lot of things that I had when I was little. (Shannon, 16)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Treiber, D.N. Is It Who Am I or Who Do You Think I Am? Identity Development of Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders. 2019. Available online: https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/494 (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Charmaz, K.; Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Strategies of qualitative inquiry. In Grounded Theory: Objectivist and Constructivist Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 249–291. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia, J.E. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 3, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crocetti, E.; Meeus, W.H.J.; Ritchie, R.A.; Meca, A.; Schwartz, S.J. Adolescent Identity: Is This the Key to Unraveling Associations between Family Relationships and Problem Behaviors? In Parenting and Teen Drug Use; Scheier, L.M., Hansen, W.B., Scheier, L.M., Hansen, W.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, J.; Marcia, J.E. The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susman, E.J.; Dorn, L.D. Puberty. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lehalle, H. Cognitive development in adolescence: Thinking freed from concrete constraints. In Handbook of Adolescent Development; Jackson, S., Goossens, L., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B.B.; Larson, J. Peer relationships in adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Vol. 2 Contextual Influences on Adolescent Development, 3rd ed.; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroger, J. Identity Development: Adolescence through Adulthood, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.J. The evolution of Eriksonian and, neo-Eriksonian identity theory and research: A review and integration. Identity Int. J. Theory Res. 2001, 1, 7–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J. A new identity for identity research: Recommendations for expanding and refocusing the identity literature. J. Adolesc. Res. 2005, 20, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Morrow, J.D. Neurobiology of adolescent substance use disorders. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Jones, R.M.; Somerville, L.H. Braking and accelerating of the adolescent brain. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Booysen, L.A.E. Workplace identity construction: An intersectional-identity-cultural lens. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management; Ramon, J.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: http://business.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.001.0001/acrefore-9780190224851-e-47 (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. ‘An integrative theory of intergroup conflict’. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Spears, R. Group identities: The social identity perspective. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.M.; Creary, S.J. Navigating the self in diverse work contexts. Oxf. Handb. Divers. Work 2013, 1, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvesson, M.; Ashcraft, K.L.; Thomas, R. Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAdams, D.P. Narrative identity. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, S. Symbolic Interactionism: A Social Structural Version; Benjamin Cummings: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, D.A.; Anderson, L. Identity work among the homeless: The verbal construction and avowal of personal identities. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 1336–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Willmott, H. Identity regulation as organizational control: Producing the appropriate individual. Lund Univ. Sch. Econ. Manag. Inst. Econ. Res. Work. Pap. Ser. 2002, 15, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, M.; De Fina, A.; Schiffrin, D. Discourse and identity construction. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; James, L. Possible identities. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Philadelphia, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, G.A.P.; Pereira, C.P.; de Sousa Pinto, M.S. “Drugs are a taboo”: A qualitative and retrospective study on the role of education and harm reduction strategies associated with the use of psychoactive substances under the age of 18. Harm Reduct. J. 2021, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessor, R. New Perspectives on Adolescent Risk Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Midford, R. Drug prevention programmes for young people: Where have we been and where should we be going? Addiction 2010, 105, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, G.; Carvalhosa, M.B.; Sznitman, G.A.; Van Petegem, S.; Baudat, S.; Darwiche, J.; Antonietti, J.P.; Clémence, A. Risk-taking behaviors in adolescence: Components of identity building? Enfance 2017, 2, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, K.C.; Botzet, A.M.; Fahnhorst, T.; Stinchfield, R.; Koskey, R. Adolescent substance abuse treatment: A review of evidence-based research. In Adolescent Substance Abuse; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.A. Recovery supports for young people: What do existing supports reveal about the recovery environment? Peabody J. Educ. 2014, 89, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godley, M.D.; Godley, S.H.; Dennis, M.L.; Funk, R.; Passetti, L.L. Preliminary outcomes from the assertive continuing care experiment for adolescents discharged from residential treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2002, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, J.D.; Boyd, J.E. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2150–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet 2006, 367, 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, M.C.; Scott, R.R. Stigma, deviance, and social control. In The Dilemma of Difference; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J.; Stuber, J.; Galea, S. Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007, 88, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Commission on Drug Policy. Classification of Psychoactive Substances: When Science was left behind. 2019. Available online: https://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/reports/classification-psychoactive-substances (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Chandra, A.; Minkovitz, C.S. Factors that influence mental health stigma among 8th grade adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2007, 36, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, C.; Rodriguez, K.L. Learning from the experiences of self-identified women of color activists. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2012, 53, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg, L. When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, E.; Schwartz, H.L. Drawing from the margins: Grounded theory research design and EDI studies. In Handbook of Research Methods on Diversity Management, Equality, and Inclusion at Work; Booysen, L., Bendl, R., Pringle, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 660–708. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.E. Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kools, S.; McCarthy, M.; Durham, R.; Robrecht, L. Dimensional analysis: Broadening the conception of grounded theory. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekhus, W. Peacocks, Chameleons, Centaurs: Gay Suburbia and the Grammar of Social Identity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Augelli, A.R.; Grossman, A.H. Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. J. Interpers. Violence 2001, 16, 1008–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decena, C.U. Tacit Subjects: Belonging and Same-Sex Desire among Dominican Immigrant Men; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harper, M.S.; Dickson, J.W.; Welsh, D.P. Self-silencing and rejection sensitivity in adolescent romantic relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locker, T.K.; Heesacker, M.; Baker, J.O. Gender similarities in the relationship between psychological aspects of disordered eating and self-silencing. Psychol. Men Masc. 2012, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Markus, R.H. Possible selves and delinquency. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Cumsille, P.; Caldwell, L.L.; Dowdy, B. Predictors of adolescents’ disclosure to parents and perceived parental knowledge: Between-and within-person differences. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilton-Weaver, L.; Kerr, M.; Pakalniskeine, V.; Tokic, A.; Salihovic, S.; Stattin, H. Open up or close down: How do parental reactions affect youth information management? J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Packer, M.J. Social cognition and self-concept: A socially contextualized model of identity. In What’s Social about Social Cognition? Research on Socially Shared Cognition in Small Groups; Nye, J.L., Brower, A.M., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, L.; Wegner, D.M. Covering up what can’t be seen: Concealable stigma and mental control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, J.B.; Twohig, M.P.; Waltz, T.; Hayes, S.C.; Roget, N.; Padilla, M.; Fisher, G. An investigation of stigma in individuals receiving treatment for substance abuse. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 1331–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrop, E.; Catalano, R.F. Evidence-based prevention for adolescent substance use. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.F.; Fagan, A.A.; Gavin, L.E.; Greenberg, M.T.; Irwin, C.E., Jr.; Ross, D.A.; Shek, D.T. Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morral, A.R.; McCaffrey, D.F.; Ridgeway, G. Effectiveness of community-based treatment for substance-abusing adolescents: 12-month outcomes of youths entering phoenix academy or alternative probation dispositions. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2004, 18, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, R.E. A Model of Self-Transformative Identity Development in Troubled Adolescent Youth. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2007. Unpublished. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waterman, A.S. Personal expressiveness: Philosophical and psychological foundations. J. Mind Behav. 1990, 11, 47–73. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.antioch.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=1990-25314-001&site=ehost-live&scope=site (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- White, W.L. Recovery/remission from substance use disorders: An analysis of reported outcomes in 415 scientific reports, 1868–2011. In Drug & Alcohol Findings Review Analysis; Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disability Services and the Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://archive.org/details/2012RecoveryRemissionFromSubstanceUseDisordersFinal (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Waterman, A.S. Identity formation: Discovery or creation? J. Early Adolesc. 1984, 4, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.J. The Mindful Brain in Psychotherapy: How Neural Plasticity and Mirror Neurons Contribute to Emotional Well-Being; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, D.J. Mindsight; Bantam/Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, D. Student voice in secondary schools: the possibility for deeper change. J. Educ. Adm. 2018, 56, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bases of Comparison | Social Identity Theory | Critical Identity Theory | Narrative Identity | Identity Work | Possible Identities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Concept of Self/Identity | Both a person’s knowledge that he or she belongs to a social group or category, as well as how one feels about that belonging | Identities are multiple, shifting, competing, temporary, context-sensitive, and evolving manifestations of subjective meanings and experiences in the social worldSocioeconomic, institutional, cultural, and historical boundaries play a significant role in the categories within which an individual or group exist | Allows the individual to present a story that is a reflection of the person in social context and all the messiness that comes along with a constant reconstruction of identity based on that interaction with social context | Range of activities individuals engage in to create, present, and sustain personal identities that are congruent with and supportive of the self-concept | Future-oriented components of self-concept are the possible selves that we could become, would like to become, and are afraid we might become |

| Meaning-Making | Derive value or meaning of our own group, social comparison between groups occurs to categorize in-group and out-group and to identify with one’s own group | Context, social meaning, power disparities, and historical intergroup conflict affect the meaning making process of identity formation | Internalized and evolving story of the self that a person constructs to make sense and meaning out of his or her life | Tactic used by people to get a greater understanding of who they are | Selves validated by others will become part of one’s identity Partners in identity negotiation provide feedback on the self; affect sense of self being developed and congruency with the future self |

| Tactic to Achieve and Sustain Positive Sense of Self | Group memberships fulfill the need for self-enhancement, belongingness, and differentiation | Challenge the status and power relations that are a part of identity | No single narrative frame can possibly organize everyday social life, and thus selves are constantly revised through repeated narrative encounters | Work done is to ensure that the world around them sees the self that is consistent with how the individual sees him/herself | Future self provides a sense of potential and an interpretive lens for the individual’s life |

| Response to Threatened Identity | Social mobility, social creativity, and social competition | Critical identity theorists do not examine social threats and responses the way that social identity theorists do, but understand difference as always contextualized in power relations | People perform their narrative identities in accordance with particular social situations and in respect to specific discourse | Distancing, dispelling, living up to idealized images, and feigning indifference | People are motivated toward futures they believe they can attain and avoid futures out-group members might attain |

| Agency | Uses tactics to make self-enhancing comparisons between groups | Looks to determine root causes of marginalization, stigmatization, and discrimination | Ability to reflect gender and class divisions, as well as, the patterns of economic, political, and cultural hegemony | Refers to what the individual does in order to navigate the self in social context and allows individual to claim desired identities | Possible selves are essential for putting the self into action |

| In Relation to Adolescents with SUDs | Role of social comparison, integration, and differentiation is central to identity formation and determining the saliences of particular identities in specific contexts | Construct information that is useful in the struggle against, marginalization, suffering, and oppression; agency and liberation tactics are at play | Cognitive development sets the stage for narrative identity; adolescents with SUDs range in cognitive abilities and thus narrative reflects the ability to begin thinking about who one really is and who one wants to become | Allows adolescent to construct socially validated identity that reflects aspects central to one’s sense of self; identity claiming and re-negotiation is important | Adolescents will act either congruently with the future self or refrain from becoming congruent with a future self that is not wanted; peer groups and attachment essential in future self-definition |

| Dimension | Conditions | Processes | Consequences | Sample Narrative Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Dimension | ||||

| Seeking Belonging: The need to find belonging comes from the youth’s needs not being met, by being othered in institutions, and not meeting expectations set by social contexts; the process leads to a state of dis-ease with the self, followed by the state of the shattered self | Unrealistic expectations Being othered Developmental needs unmet | Shining the Self Suffering Raising the Red Flag Numbing the Pain Disconnecting | Dis-ease Shattered Self Recovering Self | I thought that if I surround myself with those people, then I would become one of the top people again. But then I kind of got tired of trying so hard and not actually getting it that I stopped. That’s when I first started hanging out with the popular party people. It felt good for me because it wasn’t as much pressure. (Lulu, 17) |

| Primary Dimensions | ||||

| Shining the Self: How the participants create the image externally that they do meet the expectations set before them | Popularity and perfection Family culture Feeling less than | Molding self Keeping secrets | Exhaustion Depression False perception of Self Best of the worst | It’s like you see flowers and pretty, just happy contentment, but then there’s just so much behind that isn’t a part of the story or isn’t meant to be seen in the story. The person, the main character, is really strong and they put off this really tough kind of badass front and they’re likable and stuff, but there’s just so much that they’re not saying and there’s so much more. (Cassie, 15) |

| Suffering: Occurs in reaction to the pain that has incurred in the participants’ lives and continues to incur through the many attempts to find belonging and achieve acceptance; this is a lonely process | Pain and loss Parenting styles Being different Bullying | Rebellion Experimenting Being the parent | Vulnerability to “bad” influences Anger and resentment Relapsing | And so there was a lot of pain that I didn’t know about. I couldn’t identify it. It was just like I had pain so I had to cover it up. I didn’t know what it was about. I was very, very lonely without knowing and I needed help. But I didn’t want to admit that because that would make me weak. (Cassie, 15) |

| Raising the Red Flag: Represents the attempts the participants make to ask for help; the attempts begin very explicitly with questions and disclosure moments and due to the reactions and treatment in those moments, the attempts to find help become more extreme and destructive | No one talks about it Intergenerational disconnect | Asking for help Externalizing problems Being institutionalized | Losing trust Feeling dehumanized Something wrong with me Exposure to other options | Over the summer, I had told my parents that I needed to go to the mental hospital because I wanted to die. And my mom was like, “Okay, just sleep on it and we’ll take you in the morning.” And then I lied through the admission because I realized I didn’t really want to go to the mental hospital. I just wanted my parents to acknowledge me. Even then they didn’t. (Lily, 15) |

| Numbing the Pain: The participants feel alone and have found new groups that accept them for simply participating in recreational use; this process allows the participants to continue being the false version of self that is accepted and avoid the true feelings that arise in the sober moments | Bad body image Self-hate | Promiscuity Using substances as a solution Escaping the current moment | Sexual assault Shame and guilt Older kid attention Downward spiral | I just, at all cost, didn’t want to feel pain and sadness. (Toby, 17) |

| Disconnecting: The participants let go of the pieces of themselves that are not good enough to the point where they become a void; their only identifiers are external to them, are the behaviors they participate in, or the people they are enmeshed with | Existential crisis Being unlovable Appeal of drug life Movement from family | Maintaining reputations Extreme relationships Not caring Disassociating | Becoming the void No concept of self Drugs controlling my life | But pretty quickly after that, I was very suicidal all the time and I could not be relying on drugs. I also wasn’t eating, not taking care of myself. Then when I would go home for holidays and things, I was completely covered up and I just didn’t talk to my mom and I stayed in my room. As a result, I let people use me and I got myself into some pretty bad situations. I don’t know, I wanted to be like other people so badly, but I couldn’t because I already had a taste of this other life. I couldn’t stop. I just didn’t know what to do. (Trinity, 17) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Treiber, D.; Booysen, L.A.E. Identity (Re)Construction of Female Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137022

Treiber D, Booysen LAE. Identity (Re)Construction of Female Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):7022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137022

Chicago/Turabian StyleTreiber, Danielle, and Lize A. E. Booysen. 2021. "Identity (Re)Construction of Female Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 7022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137022