Health by Words—A Content Analysis of Political Manifestos in the Portuguese Elections of 1975

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Manifestos and Political Manifestos—A Review of the Literature

2.1. Manifestos as an Object of Multidisciplinary Studies

- (1)

- The manifesto as a “product of equilibrium” in the electoral market, composed of the ideological party offer, the main responsibility of the party, and the demand assumed by the electorate;

- (2)

- The manifesto as a social reflection of the surrounding context.

2.1.1. The Manifesto as Output in the Electoral Market

2.1.2. The Manifesto as a Social Reflection

2.2. The Socioeconomic Context of the Manifestos of the Portuguese Election of 1975

- DL (Decree Law) 621/74 (Articles 21 and 27 in particular, which dealt with the way in which citizen/party groups participated in the electoral process). This DL was composed of three depending documents: DL 621-A/74 (focused on general eligibility of citizens), DL 621-B/74 (focused on the restriction of eligibility related to citizens having had political connections with the former dictatorship), and DL 621-C/74 (focused on the number of eligible citizens for the parliamentary seats).

- DL 93-c/75 (which defined the electoral capacity and eligibility of citizens).

2.3. Research Question and Current Hypothesis: Manifestos as Combined Products

- Messages of evident collective needs,

- Messages of potential collective needs,

- And messages of structuring ideals.

2.3.1. Obvious Collective Needs

2.3.2. Potential Collective Needs

2.3.3. Structural Ideals

3. Methodological Section—Empirical Analysis and Discussion

Empirical Analysis

- (1)

- Editing the document to be analyzed in a .txt file. The texts of each party are then separated by theme. The final document, including all manifestos from all parties with all topics covered, was recorded with a .txt extension.

- (2)

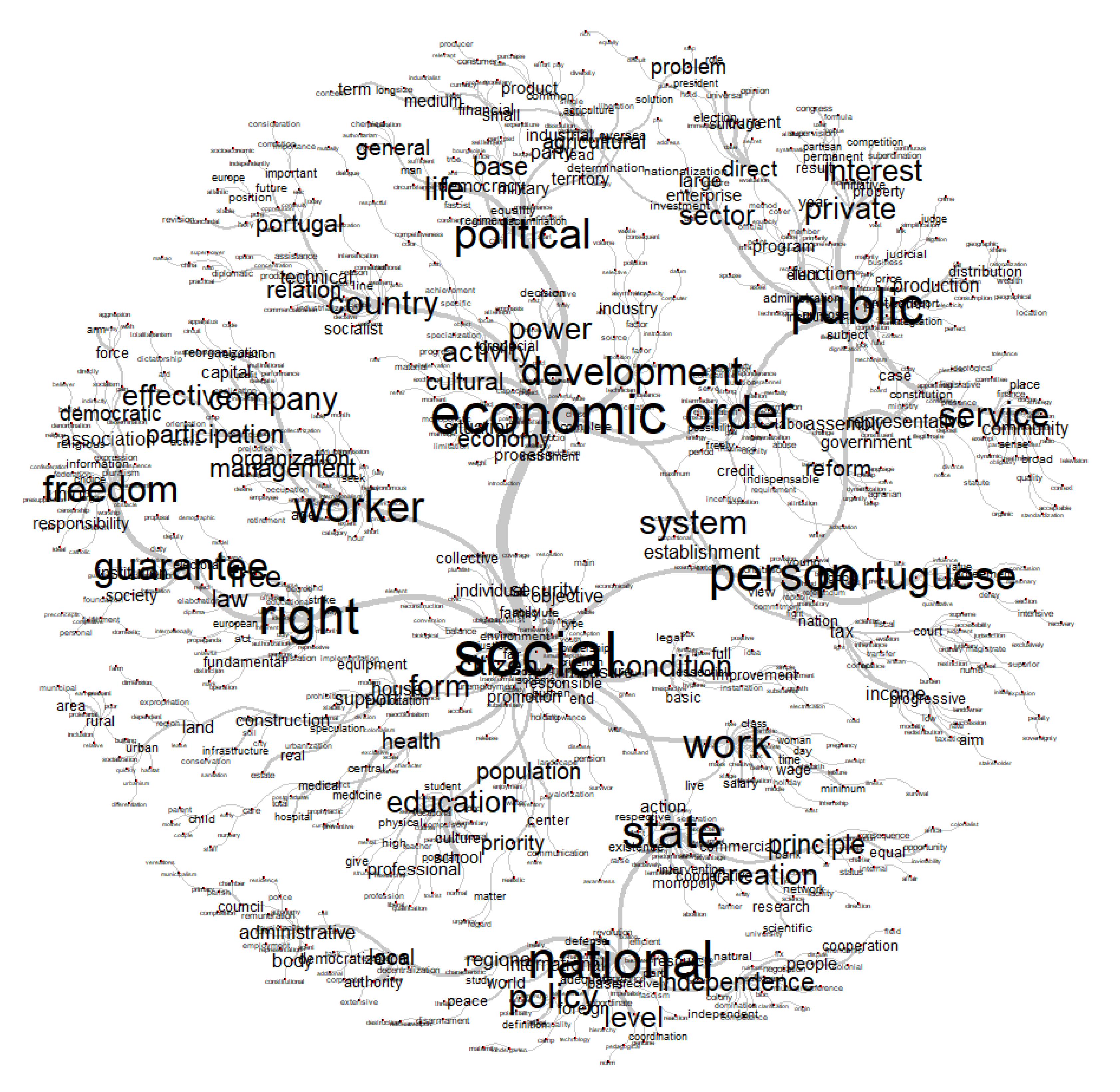

- This .txt file is then loaded into the Iramuteq software. The software then allows the selection of various parameters, namely the identification of the source language dictionary, the analysis of each word, or the reduction of each word to its root form (for example, the reduction of a verb form to its verb in the infinitive). The software also allows the identification of the priority word class (active). In our case, the active words were only three: verbs, nouns, and adjectives. This procedure minimizes, for example, problems arising from translation, while also minimizing the difference in frequency/quotation of the number of words in a sentence translated into different languages.

- (3)

- The software then allows the separate parameterization of several lines of analysis:

- (a)

- Descriptive statistical analysis;

- (b)

- Content/words factor analysis;

- (c)

- Reinert method of distribution of messages by variables;

- (d)

- Analysis of similarity by variables and analysis of text centrality.

“According to this method, the software first establishes a list of the vocabulary in the entire text, reducing words to their roots, on the basis of pre-established dictionaries (e.g., nurse and nursing reduced to a common entity nurs+). It then constructs different patterns of vocabulary distribution in order to identify discourse classes; these patterns are obtained by using automatic iterative descending hierarchical classifications to the analysed text. In other words, on the basis of their co-occurrences, pairs of words and sentences that are statistically frequently associated are gathered into the same class of discourse, and words that are less frequently associated form distinct classes. Chi-square tests provide a statistical indication of the strength of the association between vocabulary and classes: for a given class, words or excerpts that are statistically over-represented are referred to as typical, whereas those that are statistically under-represented (but relevant for other classes) are referred to as anti-typical. It is then up to the researcher to label the classes according to his or her interpretation of typical or anti-typical words or excerpts. By computing the χ2 test, the software estimated the strength of associations between classes of discourse and modalities of the following variables, extracted from the [sources].”

4. Conclusions

Further Developments

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Simone, E.; Reis Mourao, P. Rhetoric on the economy: Have European parties changed their economic messages? Appl. Econ. 2016, 48, 2022–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzhow, M.; Kelly, B.; Taddy, M. Text as data. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 535–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundler, K.; Potrafke, N. Experts and Epidemics; Working Paper n 8556; CESIfo: Munich, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, H.V.; Judkins, B. Partisanship, Trade Policy, and Globalization: Is There a Left-Right Divide on Trade Policy? Int. Stud. Q. 2004, 48, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, A.B. Parties’ Responses to Economic Globalization: What is Left for the Left and Right for the Right? Party Politics 2010, 16, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, N.D.; Martin, C.W. Economic Integration, Party Polarisation and Electoral Turnout. West Eur. Politics 2012, 35, 238–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elff, M. Social Divisions, Party Positions, and Electoral Behaviour. Elect. Stud. 2009, 28, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Lazarsfeld, P. Personal Influence: The Part Played by People in the Flow of Mass Commnunications; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, H. The structure and function of communication in society. In The Communication of Ideas; Bryson, L., Ed.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, J. As funções dos partidos nas sociedades modernas. [The functions of parties in modern societies]. Análise Soc. 1990, 25, 287–331. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, J. Democracia pluralista, partidos políticos e relação de representação. [Pluralist democracy, political parties and representation of relations]. Análise Soc. 1988, 24, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, A.; Blaum, M. Partidos políticos, movimentos de cidadãos e referendos em Portugal: Os casos do aborto e da regionalização. [Political parties, citizen movements and referenda in Portugal: The cases of abortion and regionalization]. Análise Soc. 2001, 36, 158–159. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, M.J. A imagem dos partidos e a consolidação democrática em Portugal—Resultados dum inquérito. [The image of parties and democratic consolidation in Portugal—Results of a survey]. Análise Soc. 1988, 24, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dowey, E.A., Jr. The Black Manifesto: Revolution, Reparation, Separation. Theol. Today 1969, 26, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belchior, A.M. Crise económica e perceções sobre a ideologia dos partidos políticos em Portugal (2008–2012). [Economic crisis and perceptions about the ideology of political parties in Portugal (2008–2012)]. Análise Soc. 2015, 50, 734–760. [Google Scholar]

- Fudge, C. Winning an election and gaining control: The formulation and implementation of a ‘local’ political manifesto. In Policy and Action: Essays on the Implementation of Public Policy; Methuen: London, UK, 1981; pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs, M. Elaborating the Agenda-Setting Influence of Mass Communication; Bulletin of the Institute for Communication Research, Keio University: Tokyo, Japan, 1976; Volume 7, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, P.; Elliott, P. Making the News; Longman: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Luria, A. Lenguaje y Pensamiento; Editorial Fontanella: Barcelona, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, I.; McDonald, M.D. Choices Parties Define Policy Alternatives in Representative Elections, 17 Countries 1945–1998. Party Politics 2006, 12, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisse, P. A Psicologia Experimental. [Experimental Psychology]; Gradiva: Lisbon, Portugal, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, G.; Mitchell, D. Globalization, Government Spending, and Taxation in the OECD. Eur. J. Political Res. 2001, 39, 145–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, H. The Political Economy of International Trade. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 1999, 2, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaumier, J. L’Analyse documentaire ou la valorisation des documents. Rech. Soins Infirm. 1997, 50, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pimlott, B. Parties and Voters in the Portuguese Revolution: The Elections of 1975 and 1976. Parliam. Aff. 1977, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D. Return of the Socialists: The Portuguese Election of 1983. West Eur. Politics 1983, 6, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J. L’abstention electorale au Portugal. 1975–1980. Finisterra 1983, XVIII, 65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pedreirinho, J. Propaganda Política 1976–1980. [Political Propaganda 1976–1980]. História 1981, 30, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, P. Os jornalistas na revolução portuguesa (1974–1975). [The Journalists in the Portuguese Revolution (1974–1975)]. Rev. Bras. História Mídia 2019, 7, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Palacios-Cerezales, D. Confrontación, violencia política y democratización. Portugal 1975. Política Soc. 2003, 40, 189–213. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. Psicologia das Relações Interpessoais. [Psychology of Interpersonal Relationship]; Biblioteca Pioneira de Ciências Sociais: São Paulo, Brazil, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Lisi, M. O PCP e o processo de mobilização entre 1974 e 1976. [The PCP and the process of mobilization between 1974 and 1976]. Análise Soc. 2007, 42, 181–205. [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro, A. Revolution and Utopia. A program of action in education for a society on the road to socialism—Portugal 1975. Rev. Lusófona Educ. 2007, 10, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, S. Portugal—País Macrocéfalo; Publicações Europa-América: Lisbon, Portugal, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Pinho, M. O Calcanhar de Aquiles da Economia Portuguesa. In Produtividade e Crescimento em Portugal; Economia Pura: Lisbon, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Potrafke, N. Did Globalization Restrict Partisan Politics? An Empirical Evaluation of Social Expenditures in a Panel of OECD Countries. Public Choice 2009, 140, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B. Portugal Através de Alguns Números. [Portugal through Numbers]; Prelo Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Moura, F. Relatório Preparatório do Plano Intercalar de Fomento. Economia IV. [Preparatory Report of the Interim Promotion Plan. Economy IV]. In Proceedings of ISCEF, Lisbon, Portugal, 25–26 November 1967; pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lancelot, A. As Atitudes Políticas. [Political Attitudes]; Livraria Bertrand: Lisbon, Portugal, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Domenach, J. A Propaganda Política. [Political Propaganda]; Círculo Leitores: Lisbon, Portugal, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. As Eleições Legislativas no Portugal Democrático (1975–2015). [Legislative Elections in Democratic Portugal (1975–2015)]. Anal. Soc. 2017, 52, 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, J. Portugal em Mapas e Números. [Portugal in Maps and Numbers]; Livros Horizonte: Lisbon, Portugal, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J. A Economia Portuguesa Desde 1960. [The Portuguese Economy Since 1960]; Gradiva: Lisbon, Portugal, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- de Lucca, D. Timor-Leste: Colonialismo, Descolonização, Lusutopia. [Timor-Leste: Colonialism, Decolonization, Lusutopia.]. Anal. Soc. 2017, 52, 932–940. [Google Scholar]

- Rezola, M. O movimento das forças armadas e a assembleia constituinte na revolução portuguesa (1975–1976). [The movement of the armed forces and the constituent assembly in the Portuguese revolution (1975–1976)]. História Const. 2012, 13, 635–659. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, S. Vítimas do fascismo. Os camponeses e a dinamização cultural do Movimento das Forças Armadas (1974–1975). [Victims of fascism. Peasants and the cultural dynamism of the Armed Forces Movement (1974–1975)]. Análise Soc. 2008, 43, 817–840. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, R. Um, dois, três MFA...: O Movimento das Forças Armadas na Revolução dos Cravos—Do prestígio à crise. [One, two, three MFA: The Armed Forces Movement in the Carnation Revolution—From prestige to crisis]. Rev. Bras. Hist. 2012, 32, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carapinha, R.; Vinagre, A.; Couto, J. Partidos Políticos—Ponto por Ponto. [Political Parties—Point by Point]; Editora Jornal do Fundão: Fundão, Portugal, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, A.; Bouillaguet, A. L’analyse de Contenu (Broché); PUF Editeur: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gavioli, L.; Mourao, P. Teaching Teachers for Brazilian Universities: A Content Analysis of Scientific Publications Focused on the Sustainability of Stricto Sensu Programs. High. Educ. Stud. 2019, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guessard, B. Ethique du documentaliste, éthique de l’usage de la documentation. Soins Cadres 2000, 1, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, C.G. The association method. Am. J. Psychoi. 1910, 21, 219–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, T.O. Teste de Associação de Palavras na Psicologia e Psiquiatria: História, Método e Resultados. [The Word Association Test in Psychology and Psychiatry: History, Method and Results]. Análise Psicológica 1992, 4, 531–541. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro de Mello, F. Esclarecer o Eleitor: Inquérito aos Partidos Políticos. [Clarifying the Voter: Political Party Survey]; Edições Afrodite: Lisbon, Portugal, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, D. Eleições em Abril—Diário de Campanha [Elections on April—Diary of Campaign]; Liber: Lisbon, Portugal, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles, I.; Mayer, M.; Courvoisier, N.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I. Joint analyses of open comments and quantitative data: Added value in a job satisfaction survey of hospital professionals. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marpsat, M. La Méthode Alceste. Sociologie [En Ligne], No. 1, Volume 1, 2010, mis en Ligne le 09 mai 2010. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/sociologie/312 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Jenkins, J.J. The 1952 Minnesota word association norms. In Norms of Word Association; Postman, L., Keppel, G., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, C.E. An analysis of meaning. Psychol. Rev. 1952, 59, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A. Debate eleitoral português: Presidencialização e estratégias de atenuação linguística em situação de confronto político. [Portuguese electoral debate: Presidentialization and linguistic attenuation strategies in situations of political confrontation]. Linha D’Água 2017, 30, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reinert, M. Alceste une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurelia De Gerard De Nerval. Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 1990, 26, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, M. Une méthode de classification descendante hiérarchique: Application à l’analyse lexicale par contexte. Cah. Anal. Données 1983, 8, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, S. Collaborative Writing: The English Language Learners’ gaze on art. Fórum Linguist. Florianópolis 2017, 14, 2152–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freire, A. Eleições de segunda ordem e ciclos eleitorais no Portugal democrático, 1975–2004. [Second-order elections and electoral cycles in democratic Portugal, 1975–2004]. Análise Soc. 2005, 40, 815–846. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R. Congressos partidários—O modo como os jornais os tratam. [Party congresses—The way newspapers treat them]. Comun. Cult. 2006, 2, 35–62. [Google Scholar]

- Thumb, A.; Marbe, K. Experimentelle Untersuchungen Uber die Psychologischen Grundiagen der Sprachíichen Analogiebifdung; Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Esper, E.A. A contribution to the experimental study of analogy. Psychol. Rev. 1918, 25, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ervin, S.M. Changes with age in the verbal determinants of word-association. Amer. J. Psychol. 1961, 74, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, H.; Ezrow, L.; Dorussen, H. Globalization, Party positions, and the Median Voter. World Politics 2011, 63, 509–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopes, F.; Farelo, F.; Freire, A. Partidos Políticos e Sistemas Eleitorais. [Political Parties and Electoral Systems]; Celta: Lisbon, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Word | #Cites |

|---|---|

| social | 163 |

| right | 145 |

| economic | 129 |

| national | 126 |

| politics | 125 |

| worker | 115 |

| to owe | 114 |

| public | 113 |

| form | 111 |

| company | 103 |

| medium | 102 |

| job | 99 |

| Portuguese | 97 |

| freedom | 97 |

| life | 85 |

| service | 84 |

| development | 80 |

| system | 79 |

| parents | 72 |

| creation | 72 |

| interest | 70 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mourao, P. Health by Words—A Content Analysis of Political Manifestos in the Portuguese Elections of 1975. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137119

Mourao P. Health by Words—A Content Analysis of Political Manifestos in the Portuguese Elections of 1975. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137119

Chicago/Turabian StyleMourao, Paulo. 2021. "Health by Words—A Content Analysis of Political Manifestos in the Portuguese Elections of 1975" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137119

APA StyleMourao, P. (2021). Health by Words—A Content Analysis of Political Manifestos in the Portuguese Elections of 1975. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 7119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18137119