Co-Designing Health Service Evaluation Tools That Foreground First Nation Worldviews for Better Mental Health and Wellbeing Outcomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

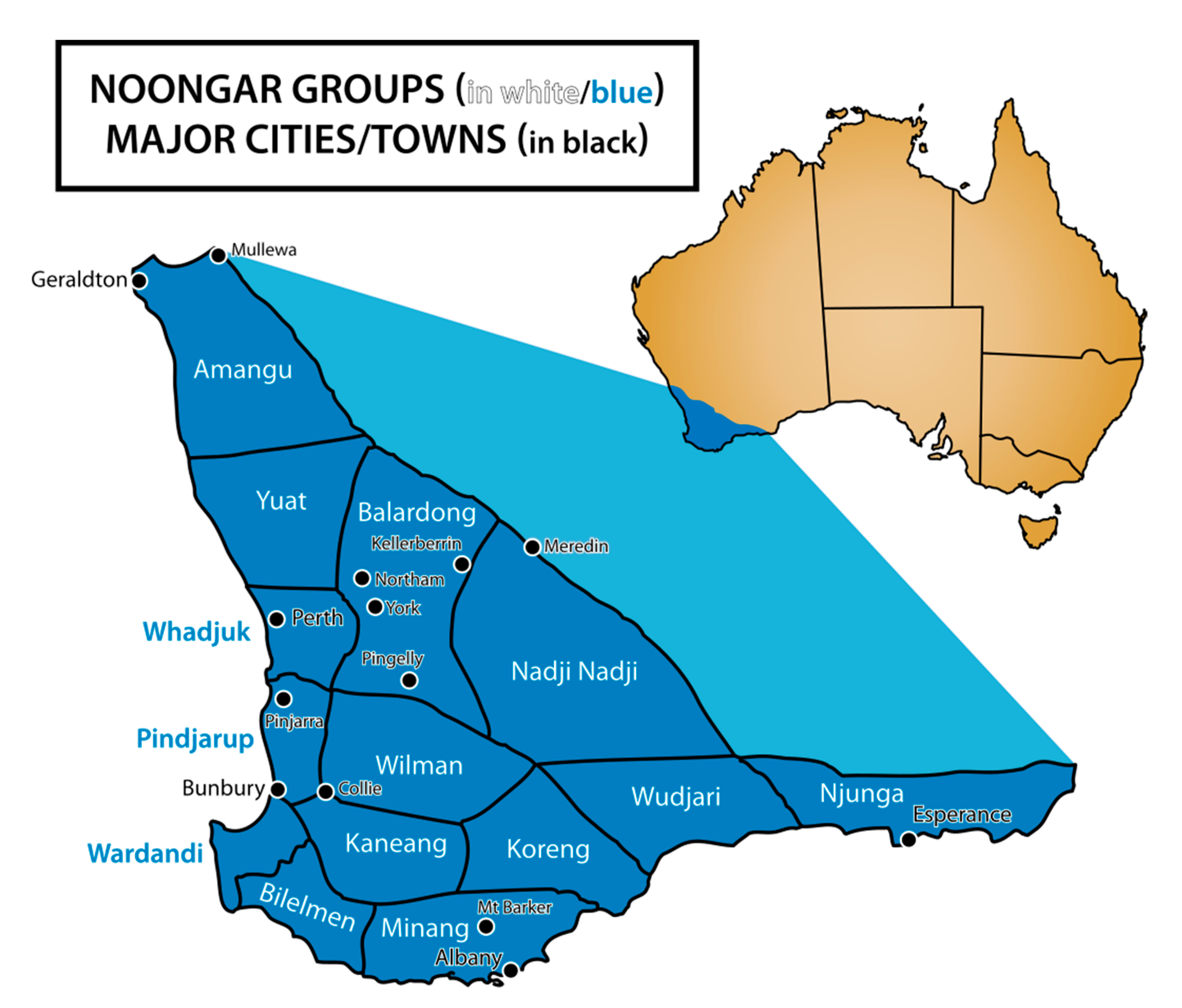

Context

2. Background Literature

Aboriginal Lived Experiences of Mental Health and Wellbeing

3. Decolonising Methodology: Engaging the Wisdom of Aboriginal Elders

3.1. Preparation for Co-Design Workshops

3.2. Makuru: Workshop One

3.3. Djilba: Workshop Two

3.4. Kambarang: Workshop Three

3.5. Analysis and Consensus Building

4. Results

4.1. Workshop Outcomes

“…a lot of people aren’t even having the thinking like you guys are doing here. Because of the Looking Forward I think there’s been this great step forward. Yeah. It’s been a step forward whereas other places in Australia it’s very spasmodic. So you might have a little fire here that’s burning and doing good things”.(Aboriginal researcher, Workshop One)

4.2. Themes and Priorities

“…really recognising the contribution that Aboriginal staff have and are making in terms of maybe it doesn’t quite ‘fit’ into the standard western society [job description form]. But it’s actually much more important in a lot of ways than this other stuff. Especially if we start to talk about people who are holding important relationships and managing the engagement with the families and the communities and stuff that’s actually enabling you know what used to be called ‘hard to reach’ people to actually engage with a service, realising just how critical that is”.(non-Aboriginal workshop participant, 2019)

“…there were a whole lot of specifics that were about how would we pursue different strategies. But I think the point that we really got to at the end of it of course was we need to step back and say ‘Well, what is the intent of this governance in the first place?”.(Non-Aboriginal workshop participant, Workshop One)

5. Discussion

5.1. Engaging Directly and Regularly with Elders as Co-Researchers

5.2. A Shared Understanding about Taking a Strengths-Based Approach

5.3. Service Staff Seek to Be Culturally Responsive but Do Not Know How

5.4. Role of Family and Community in Understanding Collective Experiences of Wellbeing and Recovery

“…We’ve talked about the human qualities or human interactions and relationships or the importance of culture within an organisation embodies through Aboriginal position, it’s probably not something that is measurable right? So I just want us to be cautious so you know? We can come up with all of these 20,000 things to measure and we should be choosing the things that matter most”.(Aboriginal researcher, Workshop One)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gwynne, K.; Jeffries, T., Jr.; Lincoln, M. Improving the efficacy of healthcare services for Aboriginal Australians. Aust. Health Rev. 2019, 43, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspin, C.; Brown, N.; Jowsey, T.; Yen, L.; Leeder, S. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudgeon, P.; Walker, R.; Scrine, C.; Shepherd, C.; Calma, T.; Ring, I. Effective Strategies to Strengthen the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. 2014. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/6d50a4d2-d4da-4c53-8aeb-9ec22b856dc5/ctgc-ip12-4nov2014.pdf.aspx (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Anderson, I.; Robson, B.; Connolly, M.; Al-Yaman, F.; Bjertness, E.; King, A.; Tynan, M.; Madden, R.; Bang, A.; Coimbra, C.E.A.; et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet-Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): A population study. Lancet 2016, 388, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Saggers, S.; Taylor, K.; Pearce, G.; Massey, P.; Bull, J.; Odo, T.; Thomas, J.; Billycan, R.; Judd, J.; et al. “Makes you proud to be black eh?”: Reflections on meaningful indigenous research participation. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S.C.; Gray, H.; Huria, T.; Lacey, C.; Beckert, L.; Pitama, S.G. Reported Māori consumer experiences of health systems and programs in qualitative research: A systematic review with meta-synthesis. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.; Gee, G.; Brown, S.J.; Atkinson, J.; Herrman, H.; Gartland, D.; Glover, K.; Clark, Y.; Campbell, S.; Mensah, F.K.; et al. Healing the Past by Nurturing the Future-co-designing perinatal strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents experiencing complex trauma: Framework and protocol for a community-based participatory action research study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verbiest, M.E.; Corrigan, C.; Dalhousie, S.; Firestone, R.; Funaki, T.; Goodwin, D.; Grey, J.; Henry, A.; Humphrey, G.; Jull, A.; et al. Using codesign to develop a culturally tailored, behavior change mHealth intervention for indigenous and other priority communities: A case study in New Zealand. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mulvale, G.; Moll, S.; Miatello, A.; Robert, G.; Larkin, M.; Palmer, V.J.; Powell, A.; Gable, C.; Girling, M. Codesigning health and other public services with vulnerable and disadvantaged populations: Insights from an international collaboration. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chino, M.; Debruyn, L. Building true capacity: Indigenous models for indigenous communities. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laveaux, D.; Christopher, S. Contextualizing CBPR: Key Principles of CBPR meet the Indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin 2009, 7, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tobias, J.K.; Richmond, C.A.M.; Luginaah, I. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) with indigenous communities: Producing respectful and reciprocal research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Eth. 2013, 8, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council. The South West Native Title Settlement. 2021. Available online: https://www.noongar.org.au/about-settlement-agreement (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Dudgeon, P.; Bray, A.; Smallwood, G.; Walker, R.; Dalton, T. Wellbeing and Healing Through Connection and Culture; Lifeline Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, R.; Quinn, S.; Wilson, B.; Abbott, T.; Cairney, S. Structural modelling of wellbeing for Indigenous Australians: Importance of mental health. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fogarty, W.; Lovell, M.; Langenberg, J.; Heron, M.J. Deficit Discourse and Strengths-based Approaches: Changing the Narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Wellbeing; The Lowitja Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm, A.F.; Bourchier, S.J.; Cvetkovski, S.; Stewart, G. Mental health of Indigenous Australians: A review of findings from community surveys. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 198, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudgeon, P.; Bray, A.; Darlaston-Jones, D.; Walker, R. Aboriginal Participatory Action Research: An Indigenous Research Methodology Strengthening Decolonisation and Social and Emotional Wellbeing; Discussion Paper; The Lowitja Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalkrishnan, N. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health: Considerations for Policy and Practice. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.L.; Anderson, K.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Tong, A.; Whop, L.J.; Cass, A.; Dickson, M.; Howard, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s domains of wellbeing: A comprehensive literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 233, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.P.; Thompson, S.C. Closing the (service) gap: Exploring partnerships between Aboriginal and mainstream health services. Aust. Health Rev. 2011, 35, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, M.; Doery, K.; Dance, P.; Chapman, J.; Gilbert, R.; Williams, R.; Lovett, R. Defining the Indefinable: Descriptors of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Cultures and Their Links to Health and Wellbeing; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Team, Research School of Population Health, The Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sivak, L.; Westhead, S.; Richards, E.; Atkinson, S.; Richards, J.; Dare, H.; Zuckermann, G.A.; Gee, G.; Wright, M.; Rosen, A.; et al. Language Breathes Life”-Barngarla Community Perspectives on the Wellbeing Impacts of Reclaiming a Dormant Australian Aboriginal Language. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calma, T.; Dudgeon, P.; Bray, A. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing and Mental Health. Aust. Psychol. 2017, 52, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nilson, C.; Kearing-Salmon, K.A.; Morrison, P.; Fetherston, C. An ethnographic action research study to investigate the experiences of Bindjareb women participating in the cooking and nutrition component of an Aboriginal health promotion programme in regional Western Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3394–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, M.; O’Connell, M. Negotiating the right path: Working together to effect change in healthcare service provision to Aboriginal peoples. Action Learn. Action Res. 2015, 21, 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.; O’Connell, M.; Jones, T.; Walley, R.; Roarty, L. Looking Forward Aboriginal Mental Health Project Final Report; Telethon Kids Institute: Subiaco, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Farnbach, S.; Gee, G.; Eades, A.M.; Evans, J.R.; Fernando, J.; Hammond, B.; Simms, M.; DeMasi, K.; Hackett, M.L. ‘We’re here to listen and help them as well’: A qualitative study of staff and Indigenous patient perceptions about participating in social and emotional wellbeing research at primary healthcare services. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lwembe, S.; Green, S.A.; Chigwende, J.; Ojwang, T.; Dennis, R. Co-production as an approach to developing stakeholder partnerships to reduce mental health inequalities: An evaluation of a pilot service. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2017, 18, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schultz, R.; Cairney, S. Caring for country and the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 207, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harfield, S.; Pearson, O.; Morey, K.; Kite, E.; Canuto, K.; Glover, K.; Gomersall, J.S.; Carter, D.; Davy, C. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Keefe, V.M.; Cwik, M.F.; Haroz, E.E.; Barlow, A. Increasing culturally responsive care and mental health equity with indigenous community mental health workers. Psychol. Serv. 2021, 18, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnican, C.; O’Toole, G. Exploring the incidence of culturally responsive communication in Australian healthcare: The first rapid review on this concept. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Jarvis, G.E. Culturally Responsive Services as a Path to Equity in Mental Healthcare. HealthcarePapers 2019, 18, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.; Lindsay, N.; King, J.; Loewen, D. Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia health care. AlterNative 2017, 13, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. Ngaa-bi-nya Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander program evaluation framework. Eval. J. Aust. 2018, 18, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thurber, K.A.; Thandrayen, J.; Banks, E.; Doery, K.; Sedgwick, M.; Lovett, R. Strengths-based approaches for quantitative data analysis: A case study using the Australian Longitudinal Study of Indigenous Children. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 12, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togni, S.J. The Uti Kulintjaku Project: The Path to Clear Thinking. An Evaluation of an Innovative, Aboriginal-Led Approach to Developing Bi-Cultural Understanding of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust. Psychol. 2017, 52, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovill, M.; Chamberlain, C.; Bennett, J.; Longbottom, H.; Bacon, S.; Field, B.; Hussein, P.; Berwick, R.; Gould, G.; O’Mara, P. Building an Indigenous-Led Evidence Base for Smoking Cessation Care among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women during Pregnancy and Beyond: Research Protocol for the Which Way? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.; Brown, A.; Dudgeon, P.; McPhee, R.; Coffin, J.; Pearson, G.; Lin, A.; Newnham, E.; Baguley, K.K.; Webb, M.; et al. Our journey, our story: A study protocol for the evaluation of a co-design framework to improve services for Aboriginal youth mental health and well-being. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVallie, C.; Sasakamoose, J. Reflexive Reflection Co-created with Kehte-ayak (Old Ones) as an Indigenous Qualitative Methodological Data Contemplation Tool. Int. J. Indig. Health 2021, 16, 208–224. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.R. Research as Intervention: Engaging silenced voices. Action Learn. Action Res. J. 2011, 17, 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, R. Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in Indigenous research. Res. Eth. 2018, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikelame, M.J.; Swartz, L. Decolonising research methodologies: Lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa. Glob. Health Action 2019, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kendall, E.; Barnett, L. Principles for the development of Aboriginal health interventions: Culturally appropriate methods through systemic empathy. Ethn. Health 2015, 20, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J. Engaging with Indigenous Australia—Exploring the Conditions for Effective Relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, Australia, 2013.

- Slay, J.; Stephens, L. Co-Production in Mental Health: A Literature Review; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Busija, L.; Cinelli, R.; Toombs, M.R.; Easton, C.; Hampton, R.; Holdsworth, K.; Macleod, B.A.; Nicholson, G.C.; Nasir, B.F.; Sanders, K.M.; et al. The Role of Elders in the Wellbeing of a Contemporary Australian Indigenous Community. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, J.; Chambers, B. Older Indigenous Australians: Their integral role in culture and community. Aust. J. Ageing 2007, 26, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Lin, A.; O’Connell, M. Humility, inquisitiveness, and openness: Key attributes for meaningful engagement with Nyoongar people. Adv. Ment. Health 2016, 14, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessarab, D.; Ng’andu, B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 2010, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wain, T.; Sim, M.; Bessarab, D.; Mak, D.; Hayward, C.; Rudd, C. Engaging Australian Aboriginal narratives to challenge attitudes and create empathy in health care: A methodological perspective. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, M.; Culbong, T.; Crisp, N.; Biedermann, B.; Lin, A. “If you don’t speak from the heart, the young mob aren’t going to listen at all”: An invitation for youth mental health services to engage in new ways of working. Early Int. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 1506–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durie, M.H.; Kingi, T.K.R. A Framework for Measuring Maori Mental Health Outcomes. A Report Prepared for the Ministry of Health; Department of Maori Studies, Massey University: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Snowshoe, A.; Crooks, C.V.; Tremblay, P.F.; Craig, W.M.; Hinson, R.E. Development of a Cultural Connectedness Scale for First Nations Youth. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Getting it Right Collaborative Group. Getting it Right: Validating a culturally specific screening tool for depression (aPHQ-9) in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Western Australian Primary Health Alliance. WA Primary Health Alliance Outcomes Framework. 2018. Available online: https://www.wapha.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/WAPHA-Outcomes-Data-Set-User-Guide-27-Jun-2018.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network. Development of the Your Experience of Service Community Managed Organisation (YES CMO) Survey and the Your Experience of Service Community Managed Organisation Short Form (YES CMO SF); Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Sveiby, K.-E. Collective leadership with power symmetry: Lessons from Aboriginal prehistory. Leadership 2011, 7, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbie-Smith, G.; Wynn, M.; Richmond, A.; Rennie, S.; Green, M.; Hoover, S.M.; Watson-Hopper, S.; Nisbeth, K.S. Stakeholder-driven, consensus development methods to design an ethical framework and guidelines for engaged research. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image, Revised ed.; Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.; Cairney, S.; Gunthorpe, W.; Paradies, Y.; Sayers, S. Strong Souls: Development and validation of a culturally appropriate tool for assessment of social and emotional well-being in Indigenous youth. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, M.J.; Lalonde, C.E. Cultural Continuity as a Protective Factor against Suicide in First Nations Youth. Horizons 2008, 10, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, J.P.; Willox, A.C.; Ford, J.D.; Shiwak, I.; Wood, M.; IMHACC Team; Rigolet Inuit Community Government. Protective factors for mental health and well-being in a changing climate: Perspectives from Inuit youth in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 141, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007)—Updated 2018; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Organisational Strategies and Actions, Reviewed as Draft Evidence Statements | Governance | Workforce | Cultural Security |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wright, M.; Getta, A.D.; Green, A.O.; Kickett, U.C.; Kickett, A.H.; McNamara, A.I.; McNamara, U.A.; Newman, A.M.; Pell, A.C.; Penny, A.M.; et al. Co-Designing Health Service Evaluation Tools That Foreground First Nation Worldviews for Better Mental Health and Wellbeing Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168555

Wright M, Getta AD, Green AO, Kickett UC, Kickett AH, McNamara AI, McNamara UA, Newman AM, Pell AC, Penny AM, et al. Co-Designing Health Service Evaluation Tools That Foreground First Nation Worldviews for Better Mental Health and Wellbeing Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168555

Chicago/Turabian StyleWright, Michael, Aunty Doris Getta, Aunty Oriel Green, Uncle Charles Kickett, Aunty Helen Kickett, Aunty Irene McNamara, Uncle Albert McNamara, Aunty Moya Newman, Aunty Charmaine Pell, Aunty Millie Penny, and et al. 2021. "Co-Designing Health Service Evaluation Tools That Foreground First Nation Worldviews for Better Mental Health and Wellbeing Outcomes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168555

APA StyleWright, M., Getta, A. D., Green, A. O., Kickett, U. C., Kickett, A. H., McNamara, A. I., McNamara, U. A., Newman, A. M., Pell, A. C., Penny, A. M., Wilkes, U. P., Wilkes, A. S., Culbong, T., Taylor, K., Brown, A., Dudgeon, P., Pearson, G., Allsop, S., Lin, A., ... O’Connell, M. (2021). Co-Designing Health Service Evaluation Tools That Foreground First Nation Worldviews for Better Mental Health and Wellbeing Outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168555