Impact of an Online Sleep and Circadian Education Program on University Students’ Sleep Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- To increase knowledge: practical advice including the impact of light/darkness on delaying or advancing circadian rhythms, napping, and caffeine, sleep environment recommendations, and other sleep hygiene tips to enhance sleep quality were embedded within course materials;

- To encourage self-reflection: self-monitoring of sleep using a sleep diary, use of an app-based lux meter to measure light levels outdoors under sunlight compared to indoor artificial lighting compared to darkness, student completion of a novel Stages of Change item to identify existing attitudes towards changing sleep behaviours, participation in surveys about sleep behaviours and sleep quality, with results of surveys fed back to students to allow comparison with cohort behavioural norms;

- To increase motivation for behavioural change: students were asked to share motivations for enrolling in the course via the online discussion board, and students selected outcome goals upon commencing the course;

- To encourage application of course content: structured discussion activities in which students were encouraged to share and analyse their own sleep habits and environments; and the final assessment comprised an advocacy-based task where students were required to write a letter to a leader in the community (e.g., high school principal) outlining how the sleep and circadian health of that community (e.g., high school students) can be improved.

2.1. Baseline Data Collection

- Demographic information: Student ID, gender, age, hours of previous sleep education, shift work completed in the previous month, and chronotype was collected. Chronotype was determined via completion of the Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire [10]. The standard scores were used to classify students into evening-types (16–41), intermediate (42–58), and morning-types (59–86);

- Sleep knowledge: Prior to starting the course, students were asked five multiple-choice questions regarding key sleep concepts. The questions tested key concepts taught in the course. Of the five questions, three questions tested practical concepts relevant to the young adult age group, and two questions tested theoretical concepts in the two-process model of sleep regulation;

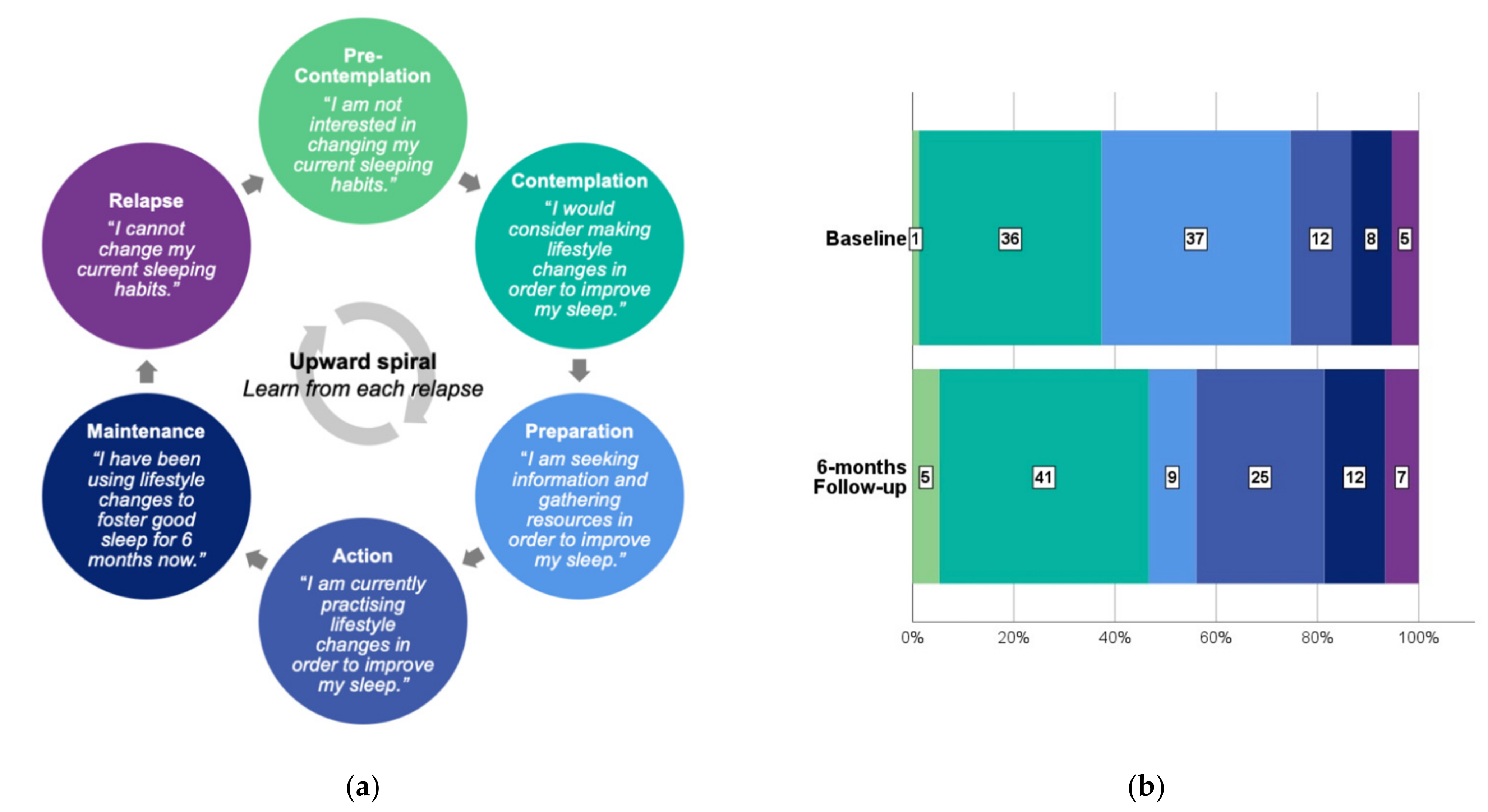

- Sleep attitudes: This question was modelled on the Stages of Change model of behavioural change [25], with each option representing one of the stages of change. Students were asked “Which statement best describes your current attitudes towards your sleep?”, with possible answers being “I am not interested in changing my current sleeping habits” (precontemplation), “I would consider making lifestyle changes to improve my sleep” (contemplation), “I am seeking information and gathering resources in order to improve my sleep” (preparation), “I am currently practicing lifestyle changes in order to improve my sleep” (action), “I have been using lifestyle changes to foster good sleep for at least 6 months now” (maintenance) and “I cannot change my current sleeping habits” (relapse). Although no standardised stages of change questions have been developed for use in sleep health promotion, various single-question items have been trialled for physical activity promotion [26];

- Student goals: Students were asked “What do you hope to achieve upon completing this course? (Select all that apply)”, with possible answers being “Complete 2 credit points of study”, “Increase my knowledge of sleep”, “Improve or change my sleep habits” and “Other (please specify)”;

- Sleep behaviours: Sleep behaviours were assessed using two scales: the Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI) [27] and the Pre-Bed Behaviour Questionnaire (PBBQ) [28]. Items on both scales were modified to remove duplication and to reflect contemporary uses of technology (Supplementary Figure S1). The SHI comprises 13 items, of which 8 were used in the current study to assess the frequency of unhealthy sleep behaviours. The original was developed in a university student sample and has been shown to have good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.66) and good test–retest reliability (r = 0.71) [27]. The original PBBQ comprised 25 items and was designed to capture common behaviours that occur in the hour prior to sleeping and was developed in high school students [28]. In the current study, the PBBQ items were simplified to 15 items by removing items that were already captured by the SHI and combining others (e.g., watching TV and watching DVDs). For both scales, the more frequent the behaviours, the poorer the sleep hygiene, and the higher the global score;

- Caffeine intake: Students were asked “On an average day, how many of the following caffeinated beverages do you usually drink?” Caffeinated beverages listed were a 250 mL energy drink, 375 mL can of cola drink, 250 mL cup of tea, 250 mL cup of coffee, short black/espresso coffee, and other. Possible answers were “0/1/2/3/4/5+.” The quantity (mg) of caffeine consumed daily was calculated from their responses [29];

- Light exposure: Light exposure was queried using three questions. These were, “On an average day, how many hours do you usually spend outdoors?”, “How long are you awake in the morning until you see sunlight? For example, opening your window or going outside.” and “Do you use any software or apps to adjust the colour display on your smartphone, laptop, or other computing devices? These might include Night Shift (Mac), Night Light (Windows), or f.lux (application)” with responses being “No/On some of my devices/On all of my devices”;

- Sleep quality: Students completed the 19-item Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The PSQI is a widely used measure of sleep quality which provides a total score (with a possible total of 21) derived from the evaluation of seven components of sleep (quality, latency, duration, efficiency, disturbance, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction) over the previous month [30]. The PSQI has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.76), moderate test–retest reliability (r = 0.64) and is modestly correlated with objective measures of sleep (r = 0.2 to 0.5) [31]. The total scores were used to categorise students into good sleepers (≤5) and poor sleepers (>5).

2.2. Follow-Up Data Collection

- Student reflection: Students were asked “Upon completing the course, did you achieve the goals you set at the beginning of the course? (Select all that apply)” with possible answers being “I completed 2 credit points of study,” “I am more knowledgeable about sleep,” “I have changed my sleep habits as a result,” “My sleep has changed as a result,” and “Other.”

2.3. Ethics Approval

2.4. Quantitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Representativeness of Follow-Up

3.2. Sleep Knowledge

3.3. Sleep Attitudes

3.4. Sleep Behaviours

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Young Adult Health and Well-Being: A Position Statement of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 758–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, S.P.; Weaver, C.C. Sleep Quality and Academic Performance in University Students: A Wake-Up Call for College Psychologists. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2010, 24, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.A.; Tavares, J.; de Azevedo, M.H. Sleep and academic performance in undergraduates: A multi-measure, multi-predictor approach. Chronobiol. Int. 2011, 28, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcio, G.; Ferrara, M.; De Gennaro, L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med. Rev. 2006, 10, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.J.; Bramoweth, A.D.; Grieser, E.A.; Tatum, J.I.; Roane, B.M. Epidemiology of insomnia in college students: Relationship with mental health, quality of life, and substance use difficulties. Behav. Ther. 2013, 44, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaultney, J.F. The prevalence of sleep disorders in college students: Impact on academic performance. J. Am. Coll. Health 2010, 59, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.L.; Zheng, X.Y.; Yang, J.; Ye, C.P.; Chen, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Xiao, Z.J. A systematic review of studies on the prevalence of insomnia in university students. Public Health 2015, 129, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.G.; Reider, B.D.; Whiting, A.B.; Prichard, J.R. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershner, S.D.; Chervin, R.D. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2014, 6, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, J.A.; Östberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, T.; Refinetti, R. Chronotype, class times, and academic achievement of university students. Chronobiol. Int. 2017, 34, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbury, R. Diurnal preference and depressive symptomatology: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, A.; Schlarb, A.A. Let’s talk about sleep: A systematic review of psychological interventions to improve sleep in college students. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 27, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, S.K.; Francis-Jimenez, C.M.; Knibbs, M.D.; Umali, I.L.; Truglio-Londrigan, M. Effectiveness of sleep education programs to improve sleep hygiene and/or sleep quality in college students: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubas, M.M.; Szklo-Coxe, M. A Critical Review of Education-Based Sleep Interventions for Undergraduate Students: Informing Future Directions in Intervention Development. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2019, 4, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, G. The Effects of an Online Sleep Hygiene Intervention on Students’ Sleep Quality; Old Dominion University: Norfolk, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kloss, J.D.; Nash, C.O.; Walsh, C.M.; Culnan, E.; Horsey, S.; Sexton-Radek, K. A ‘Sleep 101’ Program for College Students Improves Sleep Hygiene Knowledge and Reduces Maladaptive Beliefs about Sleep. Behav. Med. 2016, 42, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, S.F.; Anderson, J.L.; Hodge, G.K. Use of a supplementary internet based education program improves sleep literacy in college psychology students. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, F.C.; Buboltz, W.C., Jr.; Soper, B. Development and evaluation of the Sleep Treatment and Education Program for Students (STEPS). J. Am. Coll. Health 2006, 54, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachariae, R.; Lyby, M.S.; Ritterband, L.M.; O’Toole, M.S. Efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia—A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, L.; Reindl, R.; Zauter, S.; Hillemacher, T.; Richter, K. Effectiveness of an Online CBT-I Intervention and a Face-to-Face Treatment for Shift Work Sleep Disorder: A Comparison of Sleep Diary Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunden, S.; Rigney, G. Lessons Learned from Sleep Education in Schools: A Review of Dos and Don’ts. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, C.; Thomas, S. Behavioural Change: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Social and Public Health; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- University of Sydney. OLET1510: Health Challenges: Sleep. Available online: https://www.sydney.edu.au/units/OLET1510/2020-S2C-OL-CC (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marttila, J.; Nupponen, R. Assessing Stage of Change for physical activity: How congruent are parallel methods? Health Educ. Res. 2003, 18, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mastin, D.F.; Bryson, J.; Corwyn, R. Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. J. Behav. Med. 2006, 29, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbard, E.; Allen, N.B.; Trinder, J.; Bei, B. What’s Keeping Teenagers Up? Prebedtime Behaviors and Actigraphy-Assessed Sleep Over School and Vacation. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NSW Ministry of Health. Energy Drinks & Caffeine: The Facts. Available online: https://yourroom.health.nsw.gov.au/publicationdocuments/EnergyDrinks-facts.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2021).

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, M.; Beracci, A.; Martoni, M.; Meneo, D.; Tonetti, L.; Natale, V. Measuring Subjective Sleep Quality: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beek, A.; Weier, M.; Williams, K.; Abraham, S.; Gillum, D. College Students’ Caffeine Intake Habits and Their Perception of Its Effects. J. Educ. Dev. 2019, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lamberti, M.P.K. Improving Sleep in College Students: An Educational Intervention; University of Conneticut: Storrs, CT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin, K.L.; Sherwood, N.E.; Wolfson, J.; Pereira, M.A.; Linde, J.A. Characterizing Self-Monitoring Behavior and Its Association With Physical Activity and Weight Loss Maintenance. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2021, 15, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.; Punjabi, A.; Justesen, K.; Boyle, L.; Sherman, M.D. Encouraging Health Behavior Change: Eight Evidence-Based Strategies. Fam. Pract. Manag. 2018, 25, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bovend’Eerdt, T.J.; Botell, R.E.; Wade, D.T. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: A practical guide. Clin. Rehabil. 2009, 23, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. IS 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scullin, M.K. The Eight Hour Sleep Challenge During Final Exams Week. Teach. Psychol. 2019, 46, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallasch, J.; Gradisar, M. Relationships between sleep knowledge, sleep practice and sleep quality. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2007, 5, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Vallières, A.; Ivers, H. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): Validation of a brief version (DBAS-16). Sleep 2007, 30, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Non-Responders n = 137 n (%) | Responders n = 75 n (%) | Test Statistic, p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age median(IQR) | 20.0 (19.0–20.0) | 19.0 (18.0–20.0) | Fisher’s exact, p = 0.271 |

| 17–19 years | 68 (50) | 46 (61) | |

| 20–24 years | 65 (47) | 27 (36) | |

| 25+ years | 4 (3) | 2 (3) | |

| Gender * | χ21 = 0.087, p = 0.768 | ||

| Male | 37 (27) | 19 (25) | |

| Female | 99 (72) | 56 (75) | |

| Mark out of 100 mean(SD) | 83.1 (10.3) | 87.1 (8.4) | t210 = −2.891, p = 0.004 |

| Amount of prior sleep education | χ22 = 4.395, p = 0.111 | ||

| 0 h | 92 (67) | 59 (79) | |

| 1–5 h | 23 (17) | 11 (15) | |

| ≥6 h | 22 (16) | 5 (6) | |

| Baseline sleep knowledge score mean out of 5(SD) | 2.6 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.0) | t210 = −2.810, p = 0.005 |

| Baseline PSQI total score (mean out of 21, SD) | 6.2 (2.6) | 5.9 (3.3) | t210 = 0.823, p = 0.412 |

| Baseline PSQI categories | χ21 = 4.370, p = 0.037 | ||

| Good sleeper (PSQI ≤ 5) | 58 (42) | 43 (57) | |

| Poor sleeper (PSQI > 5) | 79 (58) | 32 (43) | |

| MEQ | χ22 = 2.028, p = 0.363 | ||

| Evening type (16–41) | 44 (32) | 21 (28) | |

| Intermediate (42–58) | 71 (52) | 36 (48) | |

| Morning type (59–86) | 22 (16) | 18 (24) | |

| Shift work in the last month | 35 (26) | 15 (20) | χ21 = 0.828, p = 0.363 |

| Sleep Concept Assessed | % Correct | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6-Month Follow-Up | |

| Two-process model of sleep regulation | 88 | 96 |

| Influence of morning light on phase advancement | 64 | 93 |

| Recommended sleep duration for young adults (18–25 years old) | 63 | 75 |

| Circadian delay in teenagers | 56 | 77 |

| Influence of napping on drive to sleep | 27 | 79 |

| Characteristic | Baseline | 6-Month Follow-Up | Test Statistic, p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Sleep Hygiene Index mean out of 32(SD) | 12.4 (4.3) | 11.4 (4.9) | t74 = 2.090, p = 0.040 |

| Modified Pre-Bed Behaviour Questionnaire mean out of 45(SD) | 15.5 (4.6) | 15.4 (5.4) | t74 = 0.135, p = 0.893 |

| Daily caffeine intake (mg) mean (SD) | 69.7 (71.9) | 83.8 (78.0) | t74 = −2.276, p = 0.026 |

| Hours awake before seeing sunlight mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.7) | t74 = 2.073, p = 0.042 |

| Hours spent outdoors mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.9) | t74 = −0.291, p = 0.772 |

| Use of blue light filters on devicesn (%) | z = −2.466, p = 0.014 | ||

| No | 12 (16) | 26 (35) | |

| On some of my devices | 29 (39) | 18 (24) | |

| On all of my devices | 34 (45) | 31 (41) |

| Characteristic | Baseline n (%) | 6-Month Follow-Up n (%) | Test Statistic, p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSQI total score mean out of 21(SD) | 5.9 (3.3) | 6.0 (3.2) | t74 = −0.194, p = 0.847 |

| Good sleep (≤5) | 43 (57) | 41 (55) | z = −0.471, p = 0.637 |

| Poor sleep (>5) | 32 (43) | 34 (45) | |

| Sleep duration | z = −1.237, p = 0.216 | ||

| ≤6 h | 8 (11) | 13 (17) | |

| 7 h | 19 (25) | 15 (20) | |

| 8 h | 24 (32) | 29 (39) | |

| ≥9 h | 24 (32) | 18 (24) | |

| Sleep quality | z = −0.554, p = 0.580 | ||

| Very good | 13 (17) | 9 (12) | |

| Fairly good | 45 (61) | 51 (68) | |

| Fairly bad | 16 (21) | 13 (17) | |

| Very bad | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | |

| Sleep latency | z = −2.118, p = 0.034 | ||

| 0–15 min | 33 (44) | 37 (49) | |

| 16–30 min | 24 (32) | 27 (36) | |

| 31–60 min | 11 (15) | 6 (8) | |

| >60 min | 7 (9) | 5 (7) | |

| Sleep efficiency | z = −0.191, p = 0.849 | ||

| ≥85% | 51 (68) | 50 (67) | |

| 75%–84% | 13 (17) | 13 (17) | |

| 65%–74% | 6 (8) | 7 (9) | |

| <65% | 5 (7) | 5 (7) | |

| Bedpartners | z = −0.975, p = 0.330 | ||

| No bedpartner | 55 (73) | 55 (73) | |

| Partner/roommate in other room | 2 (3) | 8 (11) | |

| Partner in same room but not same bed | 6 (8) | 3 (4) | |

| Partner in same bed | 12 (16) | 9 (12) | |

| Sleep medication use | z = −1.382, p = 0.167 | ||

| Not during the past month | 70 (94) | 71 (95) | |

| Less than once a week | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | |

| Once or twice a week | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Three or more times a week | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Bedtime median(IQR) | 23:59 (22:40–02:00) | 24:00 (23:00–02:00) | z = −0.828, p = 0.408 |

| Waketime median(IQR) | 9:00 (7:45–10:30) | 9:00 (7:30–10:00) | z = −2.494, p = 0.013 |

| Midpoint of sleep median(IQR) | 04:15 (03:06–06:00) | 04:19 (03:14–05:30) | z = −1.340, p = 0.180 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Semsarian, C.R.; Rigney, G.; Cistulli, P.A.; Bin, Y.S. Impact of an Online Sleep and Circadian Education Program on University Students’ Sleep Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910180

Semsarian CR, Rigney G, Cistulli PA, Bin YS. Impact of an Online Sleep and Circadian Education Program on University Students’ Sleep Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910180

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemsarian, Caitlin R., Gabrielle Rigney, Peter A. Cistulli, and Yu Sun Bin. 2021. "Impact of an Online Sleep and Circadian Education Program on University Students’ Sleep Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910180

APA StyleSemsarian, C. R., Rigney, G., Cistulli, P. A., & Bin, Y. S. (2021). Impact of an Online Sleep and Circadian Education Program on University Students’ Sleep Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910180