Communicating Electronic Adherence Data to Physicians—Consensus-Based Development of a Compact Reporting Form

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pharmacist Panel

2.2. Physician Panel

2.3. First Draft of the Reporting Form

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethic Statement

2.6. Patient and Public Involvement

3. Results

3.1. Pharmacist Panel

3.2. Physician Panel

“(…) we have the anamnesis. The patient statements, which I trust.”(P2)

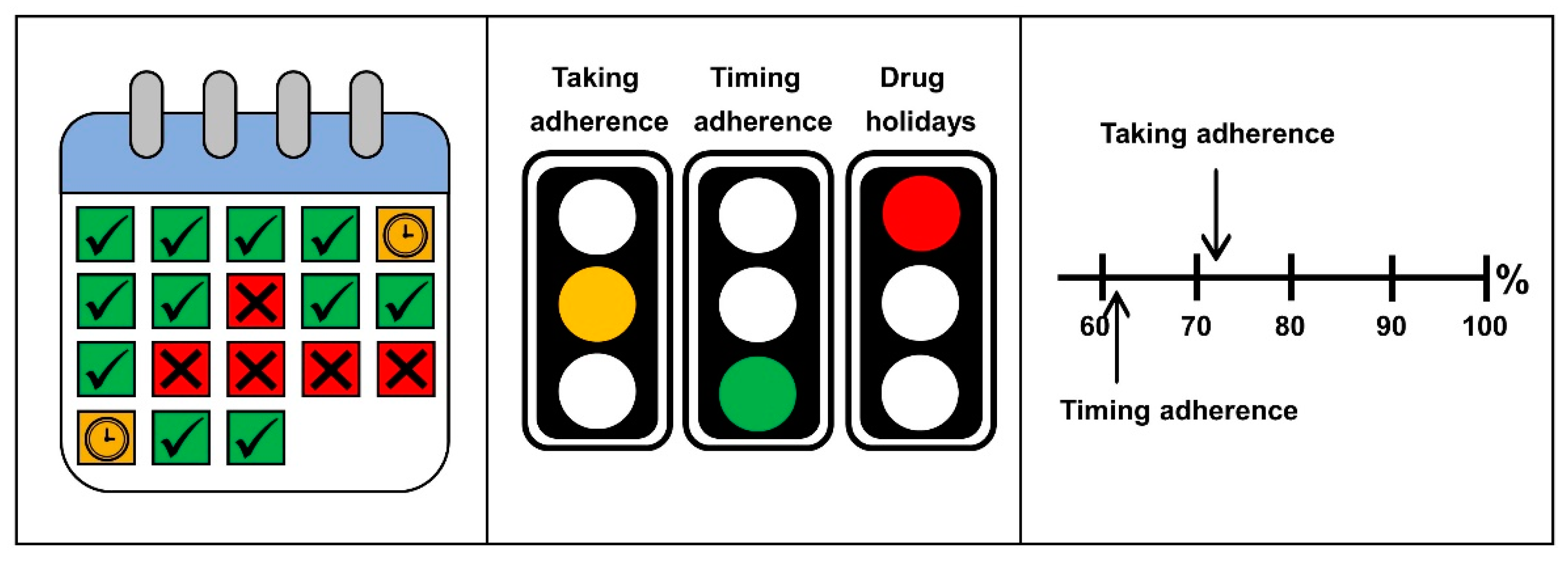

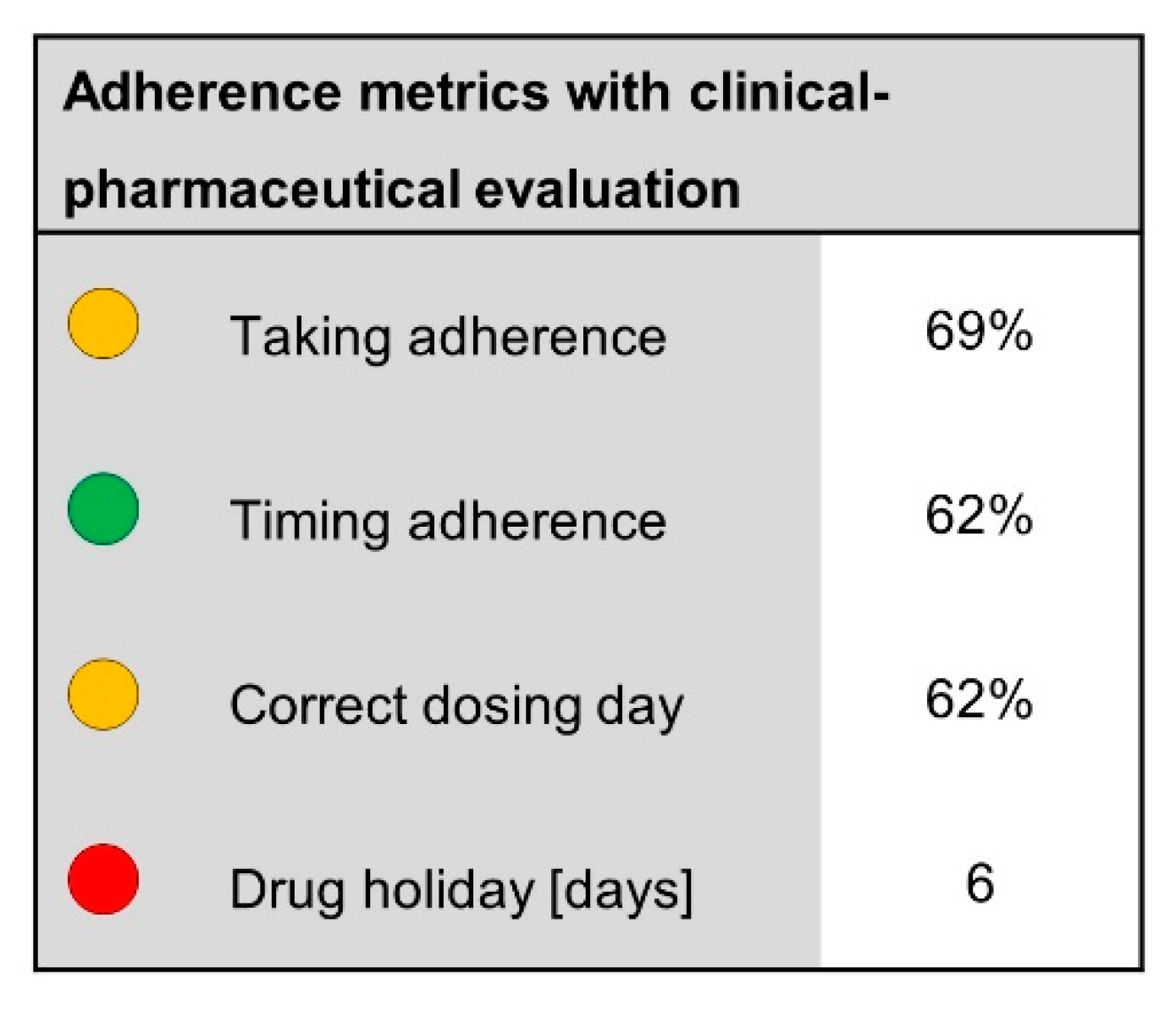

3.2.1. Adherence Calculations

“(…) after all, there are only a few drugs that you have to take at an exact time, and then it is important to me that he takes it.”(P3)

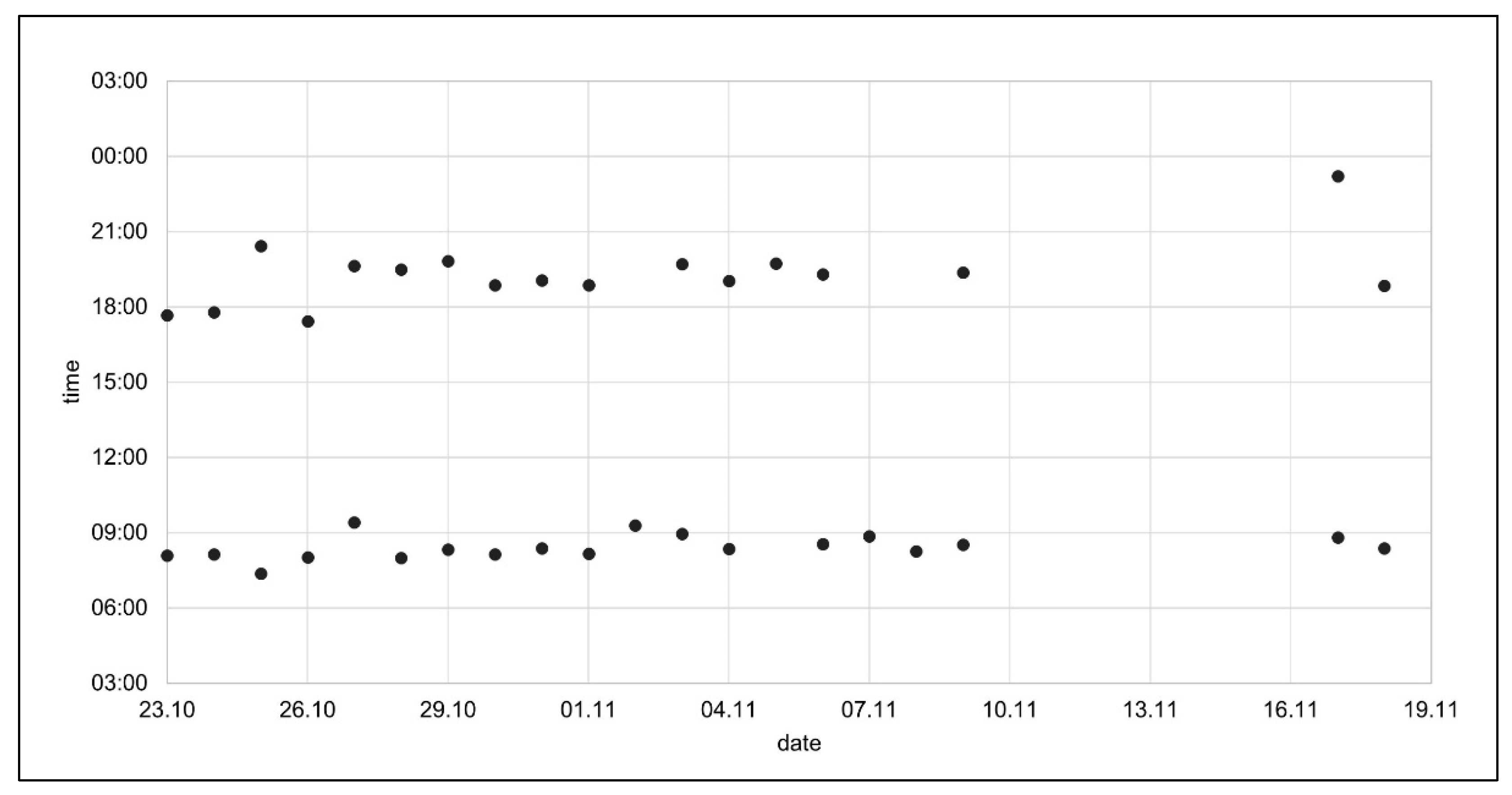

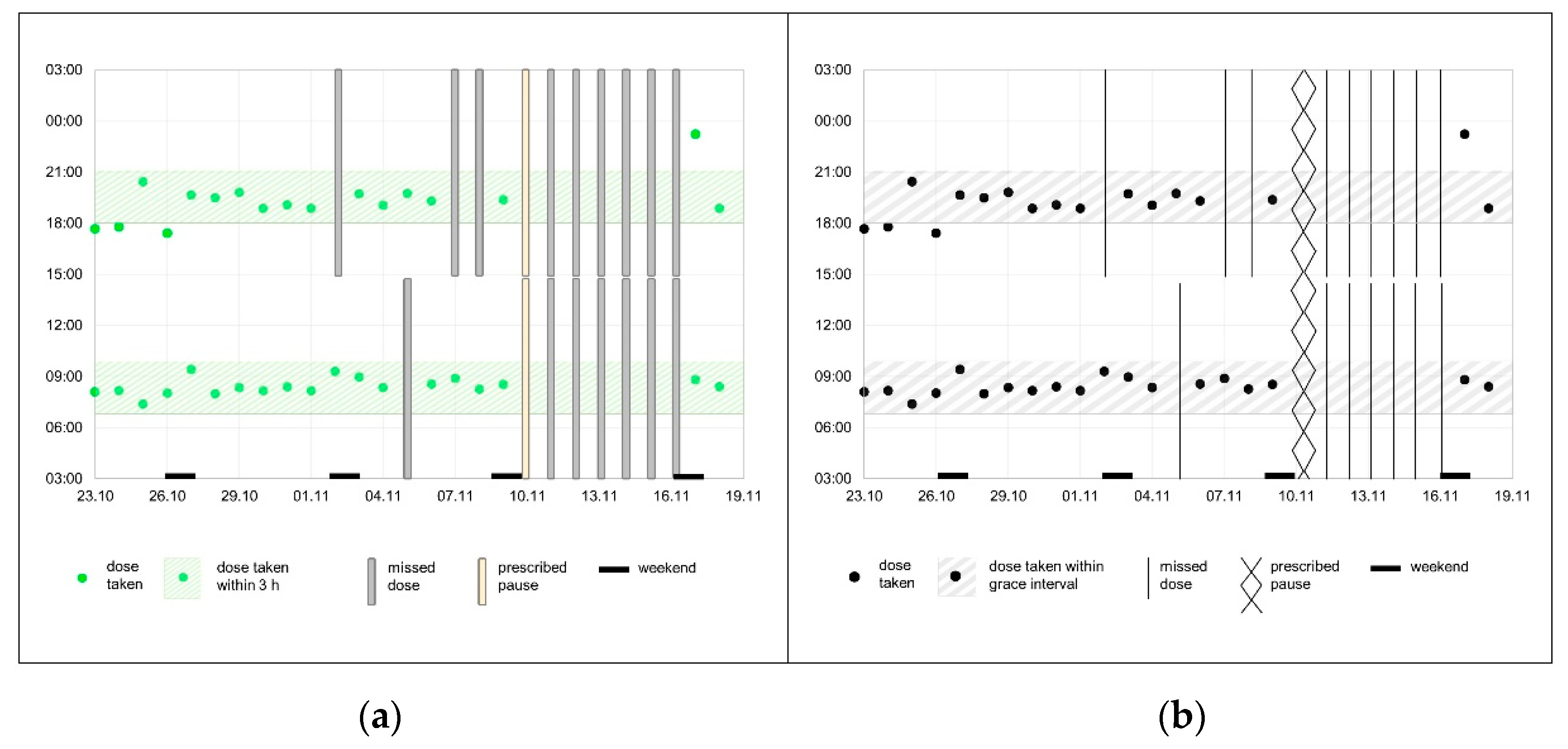

3.2.2. Graphical Representations

3.2.3. Reporting Form Structure

“I have to interpret this myself anyway, if this (forgotten tablets) is serious or not.”(P5)

3.3. First Draft of the Reporting Form

“What bothers me are the bars (…) they are a bit too massive for me (…).”(P3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Outlook

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vrijens, B.; De Geest, S.; Hughes, D.A.; Przemyslaw, K.; Demonceau, J.; Ruppar, T.; Dobbels, F.; Fargher, E.; Morrison, V.; Lewek, P.; et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharm. 2012, 73, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, R.L.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Frommer, M.; Benrimoj, C.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. Economic impact of medication nonadherence by disease groups: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, T.R.; De Geest, S.; Weber, R.; Vernazza, P.L.; Rickenbach, M.; Furrer, H.; Bernasconi, E.; Cavassini, M.; Hirschel, B.; Battegay, M.; et al. Correlates of Self-Reported Nonadherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV-Infected Patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006, 41, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrijens, B.; Antoniou, S.; Burnier, M.; de la Sierra, A.; Volpe, M. Current Situation of Medication Adherence in Hypertension. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterberg, L.; Blaschke, T. Adherence to medication. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnet, I.; Rothen, J.P.; Hersberger, K.E. Validation of a Novel Electronic Device for Medication Adherence Monitoring of Ambulatory Patients. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, H.; Kirino, S.; Remington, G.; Misawa, F.; Takeuchi, H. Adherence to Oral Antipsychotics Measured by Electronic Adherence Monitoring in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V.; Simon, G. Mining Electronic Health Records (EHRs). ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 50, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, H.B.; Zullig, L.L.; Mendys, P.; Ho, M.; Trygstad, T.; Granger, C.; Oakes, M.M.; Granger, B.B. Health information technology: Meaningful use and next steps to improving electronic facilitation of medication adherence. JMIR Med. Inform. 2016, 4, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodreads Inc. Available online: https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/5605433.William_Thomson_1st_Baron_Kelvin (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Chung, A.E.; Basch, E.M. Potential and Challenges of Patient-Generated Health Data for High-Quality Cancer Care. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lelubre, M.; Kamal, S.; Genre, N.; Celio, J.; Gorgerat, S.; Hugentobler Hampai, D.; Bourdin, A.; Berger, J.; Bugnon, O.; Schneider, M. Interdisciplinary Medication Adherence Program: The Example of a University Community Pharmacy in Switzerland. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wongvibulsin, S.; Henry, K.; Fujita, S. Quantifying and visualizing medication adherence in patients following acute myocardial infarction. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2017, 2299–2303. [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner, J.; Carline, J.D.; Durning, S.J. Is There a Consensus on Consensus Methodology? Descriptions and Recommendations for Future Consensus Research. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- openmedical AG. Available online: https://openmedical.swiss/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Lehmann, A.; Aslani, P.; Ahmed, R.; Celio, J.; Gauchet, A.; Bedouch, P.; Bugnon, O.; Allenet, B.; Schneider, M.P. Assessing medication adherence: Options to consider. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 36, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, P.C.; Haynes, R.B.; Hersberger, K.E.; Arnet, I. A Systematic Review of Medication Adherence Thresholds Dependent of Clinical Outcomes. Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, J.; de Klerk, E. Contending paradigms for the interpretation of data on patient compliance with therapeutic drug regimens. Statist. Med. 1998, 17, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterberg, L.G.; Urquhart, J.; Blaschke, T.F. Understanding forgiveness: Minding and mining the gaps between pharmacokinetics and therapeutics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 88, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenen, F.; Fourney, A.; Notman, G.; Tanner, J. Persistence of anti-hypertensive effect after ‘missed doses’ of calcium antagonist with long (amlodipine) vs short (diltiazem) elimination half-life. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996, 41, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.; Arnet, I.; Romanens, M.; Tsakiris, D.A.; Hersberger, K.E. Pattern of timing adherence could guide recommendations for personalized intake schedules. J. Pers. Med. 2012, 2, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, M. Adherence to HAART regimens. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2003, 17, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenfeld, Y.; Hunt, J.S.; Plauschinat, C.; Wong, K.S. Oral antidiabetic medication adherence and glycemic control in managed care. Am. J. Manag. Care 2008, 14, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burnier, M.; Egan, B.M. Adherence in Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1124–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pharmacists (N = 7) | Working Environment |

|---|---|

| A1 | Academic Research, Teaching |

| A2 | Community Pharmacy, Academic Research |

| A3 | Medical Laboratory Academic Research, |

| A4 | Pharmacy Associations, Academic Research |

| A5 | Community Pharmacy, Academic Research |

| A6 | Hospital Pharmacy, Academic Research |

| A7 | Community Pharmacy, Academic Research |

| Physicians (N = 5) | Working Environment |

| P1 | General Practice, Academic Research |

| P2 | Hospital |

| P3 | General Practice, Academic Research |

| P4 | Hospital, Academic Research |

| P5 | Hospital, Academic Research, Addiction Clinic |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dietrich, F.; Zeller, A.; Haag, M.; Hersberger, K.E.; Arnet, I. Communicating Electronic Adherence Data to Physicians—Consensus-Based Development of a Compact Reporting Form. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910264

Dietrich F, Zeller A, Haag M, Hersberger KE, Arnet I. Communicating Electronic Adherence Data to Physicians—Consensus-Based Development of a Compact Reporting Form. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910264

Chicago/Turabian StyleDietrich, Fine, Andreas Zeller, Melanie Haag, Kurt E. Hersberger, and Isabelle Arnet. 2021. "Communicating Electronic Adherence Data to Physicians—Consensus-Based Development of a Compact Reporting Form" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910264

APA StyleDietrich, F., Zeller, A., Haag, M., Hersberger, K. E., & Arnet, I. (2021). Communicating Electronic Adherence Data to Physicians—Consensus-Based Development of a Compact Reporting Form. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910264