Organization of Community Mental Health Services for Persons with a Severe Mental Illness and Comorbid Somatic Conditions: A Systematic Review on Somatic Outcomes and Health Related Quality of Life

Abstract

:1. Introduction

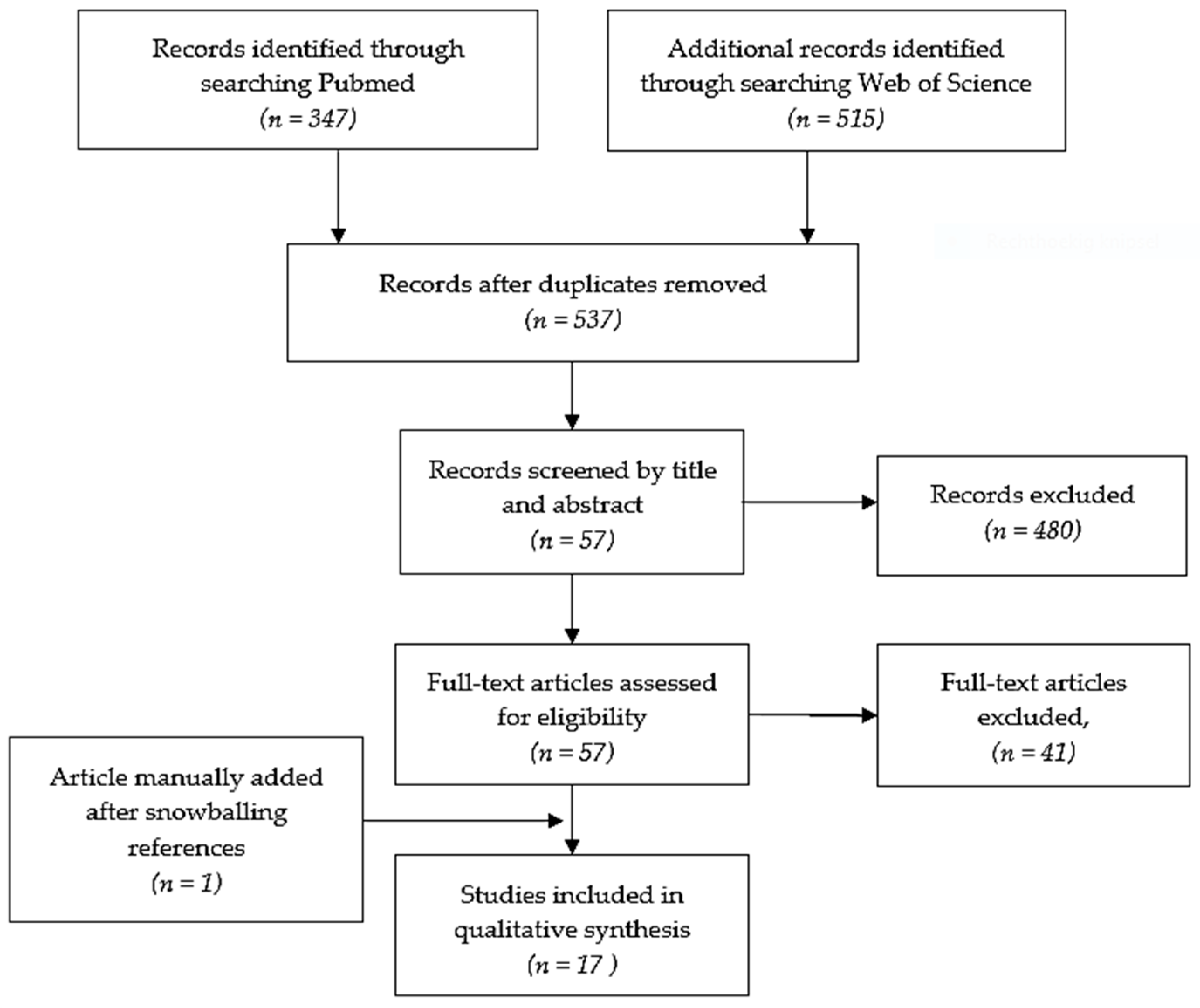

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Study Selection

2.2.1. Limits, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Quality Assessment

2.3. Data-Analysis and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment

3.2. Analysis

3.2.1. Implementation of Organizational Models of Care

3.2.2. Formal Training of Healthcare Workers

3.2.3. Educational or Coaching Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Formal Training

4.2. Implementation of Care Models

4.3. Educational and Coaching Interventions

4.4. Disciplines, Roles and Tasks

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CMHC | Community mental health center |

| CMHS | Community mental health setting |

| CONSORT | CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials |

| EPCP | Enhanced primary care pathway |

| EQ-5D | EuroQol-5 Dimension Quality of life |

| FAST | Functioning assessment short test |

| Framingham CRS | Framingham Coronary Risk Score |

| GAF | Global assessment of functioning |

| GP | General practitioner |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin (A1c) |

| HIP | Health Improvement Profile |

| HR-QOL | Health related quality of life |

| IPAQ-SF | International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form |

| LDL | Low density Lipids |

| MANSA | Manchester Short Assessment of quality of life |

| PANSS | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale |

| QOL | Quality of Life |

| RAS | Recovery assessment scale |

| ROBINS-I | Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies-of Interventions |

| SF-12 | 12-item short form survey |

| SF-36 | 36-item short form survey |

| SMI | Severe Mental Illness |

| TAU | Treatment as usual |

| TTIM | Targeted Training in Illness Management |

| VR-12 | Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey |

| WHOQoLBref | World Health Organisation Quality of Life-short version |

References

- Correll, C.U.; Detraux, J.; De Lepeleire, J.; De Hert, M. Effects of antipsychotics, antidepressants and mood stabilizers on risk for physical diseases in people with schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorder. World Psychiatr. 2015, 14, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Hert, M.; Correll, C.U.; Bobes, J.; Cetkovich-Bakmas, M.; Cohen, D.; Asai, I.; Detraux, J.; Gautam, S.; Möller, H.-J.; Ndetei, D.M.; et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatr. 2011, 10, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vancampfort, D.; Correll, C.U.; Galling, B.; Probst, M.; De Hert, M.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Gaughran, F.P.; Lally, J.A.; Stubbs, B. Diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. World Psychiatr. 2016, 15, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howell, S.; Yarovova, E.; Khwanda, A.; Rosen, S.D. Cardiovascular effects of psychotic illnesses and antipsychotic therapy. Heart 2019, 105, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappin, J.M.; Wijaya, M.; Watkins, A.; Morell, R.; Teasdale, S.B.; Lederman, O.; Rosenbaum, S.; Dick, S.; Ward, P.B.; Curtis, J. Cardio-metabolic risk and its management in a cohort of clozapine-treated outpatients. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 199, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M.; Gerhard, T.; Huang, C.; Crystal, S.; Stroup, T.S. Premature Mortality Among Adults with Schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatr. 2015, 72, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switserland, 2013; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Naslund, J.A.; Whiteman, K.L.; McHugo, G.J.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Marsch, L.A.; Bartels, S.J. Lifestyle interventions for weight loss among overweight and obese adults with serious mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatr. 2017, 47, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blomqvist, M.; Ivarsson, A.; Carlsson, I.-M.; Sandgren, A.; Jormfeldt, H. Health Effects of an Individualized Lifestyle Intervention for People with Psychotic Disorders in Psychiatric Outpatient Services: A Two Year Follow-up. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 40, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caemmerer, J.; Correll, C.U.; Maayan, L. Acute and maintenance effects of non-pharmacologic interventions for antipsychotic associated weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: A meta-analytic comparison of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 140, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Cotter, J.; Elliott, R.; French, P.; Yung, A.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1343–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Speyer, H.; Jakobsen, A.S.; Westergaard, C.; Nørgaard, H.C.B.; Pisinger, C.; Krogh, J.; Hjorthøj, C.; Nordentoft, M.; Gluud, C.; Correll, C.U.; et al. Lifestyle Interventions for Weight Management in People with Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis, Trial Sequential Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis Exploring the Mediators and Moderators of Treatment Effects. Psychother. Psychosom. 2019, 88, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deenik, J.; Czosnek, L.; Teasdale, S.B.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Tenback, D.E.; van Harten, P.N.; Tak, E.C.P.M.; Lederman, O.; et al. From impact factors to real impact: Translating evidence on lifestyle interventions into routine mental health care. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 1070–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, S.; Planner, C.; Gask, L.; Hann, M.; Knowles, S.; Druss, B.; Lester, H. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD009531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thiese, M.S. Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Biochem. Med. 2014, 24, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, E.; Kang, H. Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2018, 71, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, K.S.; Kunz, R.; Kleijnen, J.; Antes, G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Barbaresso, M.M.; Lai, Z.; Nord, K.M.; Bramlet, M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Post, E.P.; Almirall, D.; Bauer, M.S. Improving Physical Health in Patients with Chronic Mental Disorders: Twelve-Month Results from a Randomized Controlled Collaborative Care Trial. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2017, 78, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Lai, Z.; Post, E.P.; Schumacher, K.; Nord, K.M.; Bramlet, M.; Chermack, S.; Bialy, D.; Bauer, M.S. Randomized controlled trial to assess reduction of cardiovascular disease risk in patients with bipolar disorder: The Self-Management Addressing Heart Risk Trial (SMAHRT). J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2013, 74, e655–e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Druss, B.G.; Singh, M.; Von Esenwein, S.A.; Glick, G.; Tapscott, S.; Jenkins-Tucker, S.; Lally, C.; Sterling, E. Peer-Led Self-Management of General Medical Conditions for Patients With Serious Mental Illnesses: A Randomized Trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meepring, S.; Chien, W.T.; Gray, R.; Bressington, D. Effects of the Thai Health Improvement Profile intervention on the physical health and health behaviours of people with schizophrenia: A quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 27, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van der Voort, N.T.Y.G.; van Meijel, B.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; Goossens, P.J.J.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Kupka, R.W. Collaborative care for patients with bipolar disorder: Effects on functioning and quality of life. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 179, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, S.A.; Speyer, H.; Nørgaard, H.C.B.; Hjorthøj, C.; Krogh, J.; Mors, O.; Nordentoft, M. Associations between clinical and psychosocial factors and metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders—Baseline and two-years findings from the change trial. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 199, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, E.L.; Duan, L.; Cohen, H.; Kiger, H.; Pancake, L.; Brekke, J. Integrating behavioral healthcare for individuals with serious mental illness: A randomized controlled trial of a peer health navigator intervention. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 182, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwastiak, L.A.; Luongo, M.; Russo, J.; Johnson, L.; Lowe, J.M.; Hoffman, G.; McDonell, M.G.; Wisse, B. Use of a Mental Health Center Collaborative Care Team to Improve Diabetes Care and Outcomes for Patients with Psychosis. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cameron, C.M.; Nazar, J.C.; Ehrlich, C.; Kendall, E.; Crompton, D.; Liddy, A.M.; Kisely, S. General practitioner management of chronic diseases in adults with severe mental illness: A community intervention trial. Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druss, B.G.; von Esenwein, S.A.; Compton, M.T.; Rask, K.J.; Zhao, L.; Parker, R.M. A Randomized Trial of Medical Care Management for Community Mental Health Settings: The Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) Study. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2010, 167, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Druss, B.G.; Von Esenwein, S.A.; Glick, G.; Deubler, E.; Lally, C.; Ward, M.C.; Rask, K.J. Randomized Trial of an Integrated Behavioral Health Home: The Health Outcomes Management and Evaluation (HOME) Study. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2017, 174, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughran, F.; Impact on behalf of the IMPACT Team; Stahl, D.; Ismail, K.; Greenwood, K.; Atakan, Z.; Gardner-Sood, P.; Stubbs, B.; Hopkins, D.; Patel, A.; et al. Randomised control trial of the effectiveness of an integrated psychosocial health promotion intervention aimed at improving health and reducing substance use in established psychosis (IMPaCT). BMC Psychiatr. 2017, 17, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldberg, R.W.; Dickerson, F.; Lucksted, A.; Brown, C.H.; Weber, E.; Tenhula, W.N.; Kreyenbuhl, J.; Dixon, L.B. Living Well: An Intervention to Improve Self-Management of Medical Illness for Individuals With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Rojas, L.; Pulido, S.; Azanza, J.R.; Bernardo, M.; Rojo, L.; Mesa, F.J.; Martínez-Orteg, J.M. Risk factor assessment and counselling for 12 months reduces metabolic and cardiovascular risk in overweight or obese patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: The CRESSOB study. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2016, 44, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rogers, E.S.; Maru, M.; Kash-MacDonald, M.; Archer-Williams, M.; Hashemi, L.; Boardman, J. A Randomized Clinical Trial Investigating the Effect of a Healthcare Access Model for Individuals with Severe Psychiatric Disabilities. Community Ment. Heal. J. 2016, 52, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajatovic, M.; Gunzler, D.D.; Kanuch, S.W.; Cassidy, K.A.; Tatsuoka, C.; McCormick, R.; Blixen, C.E.; Perzynski, A.T.; Einstadter, U.; Thomas, C.L.; et al. A 60-Week Prospective RCT of a Self-Management Intervention for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness and Diabetes Mellitus. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speyer, H.; Nørgaard, H.C.B.; Birk, M.; Karlsen, M.; Jakobsen, A.S.; Pedersen, K.; Hjorthøj, C.; Pisinger, C.; Gluud, C.; Mors, O.; et al. The CHANGE trial: No superiority of lifestyle coaching plus care coordination plus treatment as usual compared to treatment as usual alone in reducing risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and abdominal obesity. World Psychiatr. 2016, 15, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aschbrenner, K.A.; Naslund, J.A.; Shevenell, M.; Mueser, K.T.; Bartels, S.J. Feasibility of Behavioral Weight Loss Treatment Enhanced with Peer Support and Mobile Health Technology for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Q. 2016, 87, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naslund, J.A.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Scherer, E.A.; McHugo, G.J.; Marsch, L.A.; Bartels, S.J. Wearable devices and mobile technologies for supporting behavioral weight loss among people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 244, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, S.; Ryu, J.-K.; Kim, C.-H.; Chang, J.-G.; Lee, H.-B.; Kim, D.H.; Roh, D. Preliminary Effectiveness and Sustainability of Group Aerobic Exercise Program in Patients with Schizophrenia. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, M.; Patel, A.; Stahl, D.; Gardner-Sood, P.; Mushore, M.; Smith, S.; Greenwood, K.; Onagbesan, O.; O’Brien, C.; Fung, C.; et al. Randomised controlled trial to improve health and reduce substance use in established psychosis (IMPaCT): Cost-effectiveness of integrated psychosocial health promotion. BMC Psychiatr. 2017, 17, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- White, J.; Lucas, J.; Swift, L.; Barton, G.; Johnson, H.; Irvine, L.; Abotsie, G.; Jones, M.; Gray, R.J. Nurse-Facilitated Health Checks for Persons With Severe Mental Illness: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Choi, J.S.; Choi, E.; Nieman, C.L.; Joo, J.H.; Lin, F.R.; Gitlin, L.N.; Han, H.-R. Effects of Community-Based Health Worker Interventions to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Care Among Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public. Health 2016, 106, e3–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, D.; Lin, E.; Peterson, D.; Ludman, E.; Von Korff, M.; Katon, W. Integrated medical care management and behavioral risk factor reduction for multicondition patients: Behavioral outcomes of the TEAMcare trial. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatr. 2013, 36, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scantlebury, A.; Parker, A.; Booth, A.; McDaid, C.; Mitchell, N. Implementing mental health training programmes for non-mental health trained professionals: A qualitative synthesis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrakis, M.; Robinson, R.; Myers, K.; Kroes, S.; O’Connor, S. Dual diagnosis competencies: A systematic review of staff training literature. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2018, 7, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Scantlebury, A.; Hughes-Morley, A.; Mitchell, N.; Wright, K.; Scott, W.; McDaid, C. Mental health training programmes for non-mental health trained professionals coming into contact with people with mental ill health: A systematic review of effectiveness. BMC Psychiatr. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bressington, D.; Badnapurkar, A.; Inoue, S.; Ma, H.Y.; Chien, W.T.; Nelson, D.; Gray, R. Physical Health Care for People with Severe Mental Illness: The Attitudes, Practices, and Training Needs of Nurses in Three Asian Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baxter, S.; Johnson, M.; Chambers, D.; Sutton, A.; Goyder, E.; Booth, A. The effects of integrated care: A systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgermans, L.; Marchal, Y.; Busetto, L.; Kalseth, J.; Kasteng, F.; Suija, K.; Oona, M.; Tigova, O.; Rösenmuller, M.; Devroey, D. How to Improve Integrated Care for People with Chronic Conditions: Key Findings from EU FP-7 Project Integrate and Beyond. Int. J. Integr. Care 2017, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, M.; Ruppelt, F.; Siem, A.-K.; Rohenkohl, A.C.; Kraft, V.; Luedecke, D.; Sengutta, M.; Schröter, R.; Daubmann, A.; Correll, C.U.; et al. Comorbidity of chronic somatic diseases in patients with psychotic disorders and their influence on 4-year outcomes of integrated care treatment (ACCESS II study). Schizophr. Res. 2018, 193, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosomworth, N.J. Practical use of the Framingham risk score in primary prevention: Canadian perspective. Can. Fam. Phys. 2011, 57, 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Hemann, B.A.; Bimson, W.F.; Taylor, A.J. The Framingham Risk Score: An Appraisal of Its Benefits and Limitations. Am. Hear. Hosp. J. 2007, 5, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Kim, H.-S.; Park, W.J.; Cho, G.-Y.; Choi, Y.-J. Clinical significance of framingham risk score, flow-mediated dilation and pulse wave velocity in patients with stable angina. Circ. J. 2011, 75, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mittal, V.A.; Vargas, T.; Osborne, K.J.; Dean, D.; Gupta, T.; Ristanovic, I.; Hooker, C.I.; Shankman, S.A. Exercise Treatments for Psychosis: A Review. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatr. 2017, 4, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Hallgren, M.; Firth, J.; Veronese, N.; Solmi, M.; Brand, S.; Cordes, J.; Malchow, B.; Gerber, M.; et al. EPA guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: A meta-review of the evidence and Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). Eur. Psychiatr. 2018, 54, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodgers, M.; Dalton, J.; Harden, M.; Street, A.; Parker, G.; Eastwood, A. Integrated Care to Address the Physical Health Needs of People with Severe Mental Illness: A Mapping Review of the Recent Evidence on Barriers, Facilitators and Evaluations. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Scott, D.; Platania-Phung, C. Perceptions of Barriers to Physical Health Care for People with Serious Mental Illness: A Review of the International Literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H. Organizing Care for Patients With Chronic Illness Revisited. Milbank Q. 2019, 97, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.; Howard, J.; Shaw, E.K.; Cohen, D.J.; Shahidi, L.; Ferrante, J.M. Facilitators and Barriers to Care Coordination in Patient-centered Medical Homes (PCMHs) from Coordinators’ Perspectives. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, C.; Bleasel, J.; Liu, H.; Tchan, M.; Ponniah, S.; Brown, A. Effectiveness of chronic care models: Opportunities for improving healthcare practice and health outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lean, M.; Fornells-Ambrojo, M.; Milton, A.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Harrison-Stewart, B.; Yesufu-Udechuku, A.; Kendall, T.; Johnson, S. Self-management interventions for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2019, 214, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sledge, W.H.; Lawless, M.; Sells, D.; Wieland, M.; O’Connell, M.J.; Davidson, L. Effectiveness of peer support in reducing readmissions of persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ådnanes, M.; Kalseth, J.; Ose, S.O.; Ruud, T.; Rugkåsa, J.; Puntis, S. Quality of life and service satisfaction in outpatients with severe or non-severe mental illness diagnoses. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reilly, S.; Olier, I.; Planner, C.; Doran, T.; Reeves, D.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Gask, L.; Kontopantelis, E. Inequalities in physical comorbidity: A longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabassa, L.J.; Camacho, D.; Vélez-Grau, C.M.; Stefancic, A. Peer-based health interventions for people with serious mental illness: A systematic literature review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 84, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, B.; Williams, J.; Shannon, J.; Gaughran, F.; Craig, T. Peer support interventions seeking to improve physical health and lifestyle behaviours among people with serious mental illness: A systematic review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2016, 25, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.; Gray, R.; White, J. The Health Improvement Profile: A Manual to Promote Physical Wellbeing in People with Severe Mental Illness; M&K Update: Cumbria, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bressington, D.; Chien, W.T.; Mui, J.; Lam, K.K.C.; Mahfoud, Z.; White, J.; Gray, R. Chinese Health Improvement Profile for people with severe mental illness: A cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 27, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumit, G.L.; Dickerson, F.B.; Wang, N.-Y.; Dalcin, A.; Jerome, G.J.; Anderson, C.A.; Young, D.R.; Frick, K.D.; Yu, A.; Gennusa, J.V.; et al. A Behavioral Weight-Loss Intervention in Persons with Serious Mental Illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1594–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yarborough, B.J.H.; Leo, M.C.; Stumbo, S.P.; Perrin, N.A.; Green, C.A. STRIDE: A randomized trial of a lifestyle intervention to promote weight loss among individuals taking antipsychotic medications. BMC Psychiatr. 2013, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartels, S.J.; Pratt, S.I.; Aschbrenner, K.A.; Barre, L.K.; Naslund, J.A.; Wolfe, R.; Xie, H.; McHugo, G.J.; Jimenez, D.E.; Jue, K.; et al. Pragmatic Replication Trial of Health Promotion Coaching for Obesity in Serious Mental Illness and Maintenance of Outcomes. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2015, 172, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthys, E.; Remmen, R.; Van Bogaert, P. An overview of systematic reviews on the collaboration between physicians and nurses and the impact on patient outcomes: What can we learn in primary care? BMC Fam. Pr. 2017, 18, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.; Abraham, K.M.; Bajor, L.A.; Lai, Z.; Kim, H.M.; Nord, K.M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Bauer, M.S.; Kilbourne, A.M. Quality of life among patients with bipolar disorder in primary care versus community mental health settings. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 146, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Happell, B.; Stanton, R.; Hoey, W.; Scott, D. Cardiometabolic Health Nursing to Improve Health and Primary Care Access in Community Mental Health Consumers: Baseline Physical Health Outcomes from a Randomised Controlled Trial. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 35, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boult, C.; Karm, L.; Groves, C. Improving chronic care: The “guided care” model. Perm. J. 2008, 12, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Meijel, B.; van Hamersveld, S.; van Gool, R.; van der Bijl, J.; van Harten, P. Effects and feasibility of the “traffic light method for somatic screening and lifestyle” in patients with severe mental illness: A pilot study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2015, 51, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auschra, C. Barriers to the Integration of Care in Inter-Organisational Settings: A Literature Review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Firth, J.; Siddiqi, N.; Koyanagi, A.; Siskind, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Galletly, C.; Allan, S.; Caneo, C.; Carney, R.; Carvalho, A.F.; et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: A blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatr. 2019, 6, 675–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Röhricht, F.; Waddon, G.K.; Binfield, P.; England, R.; Fradgley, R.; Hertel, L.; James, P.; Littlejohns, J.; Maher, D.; Oppong, M. Implementation of a novel primary care pathway for patients with severe and enduring mental illness. BJPsych. Bull. 2017, 41, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onwumere, J.; Shiers, D.; Gaughran, F. Physical Health Problems in Psychosis: Is It Time to Consider the Views of Family Carers? Front. Psychiatr. 2018, 9, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onwumere, J.; Howes, S.; Shiers, D.; Gaughran, F. Physical health problems in people with psychosis: The issue for informal carers. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2018, 64, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Umberson, D.; Montez, J.K. Social Relationships and Health: A Flashpoint for Health Policy. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S54–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richardson, A.; Richard, L.; Gunter, K.; Cunningham, R.; Hamer, H.; Lockett, H.; Wyeth, E.; Stokes, T.; Burke, M.; Green, M.; et al. A systematic scoping review of interventions to integrate physical and mental healthcare for people with serious mental illness and substance use disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 128, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deenik, J.; Tenback, D.E.; Tak, E.; Henkemans, O.A.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Hendriksen, I.J.M.; van Harten, P.N. Implementation barriers and facilitators of an integrated multidisciplinary lifestyle enhancing treatment for inpatients with severe mental illness: The MULTI study IV. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Osborn, D.P.J.; Burton, A.; Hunter, R.; Marston, L.; Atkins, L.; Barnes, T.; Blackburn, R.; Craig, T.K.J.; Gilbert, H.; Heinkel, S.; et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of an intervention for reducing cholesterol and cardiovascular risk for people with severe mental illness in English primary care: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatr. 2018, 5, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lokkerbol, J.; Nuijen, J.; Evers, S.; Knegtering, H.; Delespaul, P.; Kroon, H.; Bruggeman, R. A study of cost-effectiveness of treating serious mental illness: Challenges and solutions. Tijdschr. Voor Psychiatr. 2016, 58, 700–705. [Google Scholar]

- Eisman, A.B.; Kilbourne, A.M.; Dopp, A.R.; Saldana, L.; Eisenberg, D. Economic evaluation in implementation science: Making the business case for implementation strategies. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 283, 112433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Risk of Bias Tool | Participants Selection | Intervention Bias | Identification Confounders | Measurement | Total risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameron et al. [29] | ROBINS-I | Serious risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Serious |

| Chwastiak et al. [28] | CONSORT | Serious risk | Serious risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Serious |

| Druss et al. [30] | CONSORT | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low |

| Druss et al. [31] | CONSORT | Low risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Druss et al. [23] | CONSORT | Low risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Gaughran et al. [32] | CONSORT | Low risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Goldberg et al. [33] | CONSORT | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Gutiérrez-Rojas [34] | ROBINS-I | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Kelly et al. [27] | CONSORT | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low |

| Kilbourne et al. [22] | CONSORT | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Kilbourne et al. [21] | CONSORT | Low risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Meepring, S. et al. [24] | ROBINS-I | Serious risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Serious |

| Rogers et al. [35] | CONSORT | Low risk | Moderate risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Sajatovic et al. [36] | CONSORT | Low Risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Speyer et al. [37] Jakobsen et al. [26] | CONSORT | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low |

| van Der Voort et al. [25] | CONSORT | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate risk | Low risk | Moderate |

| Authors & Year | Study Design | Participants | Intervention: | Outcomes | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameron et al. [29] Australia | non-randomized interventional study | (1) Adults with SMI who attended community based public mental health services for regular administration of either depot medication or clozapine. | The ACTIVATE Mind and Body program aims to raise awareness in the public mental health, primary care and non-governmental sectors about the physical and oral health care needs of people with SMI. The intervention included: (a) distribution of care guidelines for managing physical comorbidities to GP clinics and public mental health facilities; (b) the development of a website for both health professionals and community members; (c) development of strategies so that mental health clinicians actively linked people with SMI to general practices; comparison: TAU | Outcomes: (a) synthesis of GP consultations, coded in short visits (consultation <20 min) or long visits (consultation >20 min); (b) total cost to the patient and Federal Government; (c) data on pathology tests (cardiac enzymes or marker, electrolytes, full blood examination & coagulation, liver function tests, and urea, electrolytes, creatinine lipid studies and syphilis serology.) | (1) Outcomes: (a) increased short, long and total GP consultations than the control during the trial period (p < 0.05); (b) higher mean monthly costs to government for benefits paid for all GP claims during the trial period; (c) the intervention area showed a significant increase in the use of Liver Function Tests. |

| Chwastiak et al. [28] USA | RCT (Pilot Study) | (1) Adults aged 18 to 64 years old, diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder with psychosis. (2) Diagnosed with type II diabetes at least six months before enrollment; poor diabetes control (n = 35). | Pilot study of a CMHC-based collaborative care model based TEAMcare model for type II diabetes among CMHC outpatients with psychosis: (a) a team (CMHC nurse care manager, a CMHC psychiatrist, an advanced practice nurse) provided primary care onsite at the CMHC; (b) an endocrinologist consultant); (c) clinical visits and team meetings at the CMHC; (d) team trained in TEAMcare model; (e) health assessment and individualized health plan; (f) 30-min visits for 12 weeks; (f) diabetes education materials modified to target group; (g) nurses used behavioral interventions; and (h) coordinated care with primary and specialty care; comparison: TAU. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) HbA1c after three months of intervention. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) blood Pressure; (b) tobacco use; (c) mental health symptom measures; (d) process measures (nurse care manager visits). | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) at three-month follow-up, mean HbA1c among participants randomized to the intervention decreased from 9.4% to 8.3%, being both clinically and statistically significant (p = 0.049). In the TAU group, mean HbA1c decreased from 8.3% at baseline to 8.0% and was not significant. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) both groups had statistically significant decreases in BMI (2.1 kg/m2 in intervention vs. 2.9 kg/m2 in TAU); (b) there were no significant changes in smoking or psychiatric symptoms. |

| Druss et al. [30] USA | RCT | (1) Adults with a severe mental illness. (2) In care at a Community Mental Health Center (n = 407). | (1) Care Management: (a) two full-time nurses used manualized protocol for care management; (b) provided information (medical conditions, available medical providers in the community, appointments); (c) at each meeting the client received an up-to-date booklet; (d) action plans to improve health behavior; (e) the care manager served as a liaison between medical and mental health providers; (f) coaching to help clients interact more effectively with their providers. (2) Duration: 12 Months; comparison: TAU, received contact information. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) SF-36: Health-related quality of life; (b) quality of primary care (physical examination; screening tests; vaccinations and education; (c) Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Index. | Outcomes: (a) SF-36 improved on the Mental Component Summary score (MCS), (z = −3.15, p = 0.002); (b) quality of primary care showed twice as many indicated physical examination activities(70.5% vs. 35.6%, p < 0.001), more than double the screening tests (50.4% vs. 21.6%, p < 0.001), four times as many educational interventions (80.0% vs. 18.9%, p < 0.001), and six times as many indicated vaccinations (24.7% vs. 3.8%, p < 0.001); (c) the intervention also improved on having a usual source of care (from 49.5% to 71.2%, versus 48.3% to 51.9% for usual care(p = 0.001), and more primary care visits (4.94 vs. 4.11, p = 0.02); (d) a significantly greater number of undiagnosed medical conditions were identified by the intervention (11.9% vs.1.8%, p = 0.0046); (e) the Framingham Index was significantly lower at one year in the intervention group (6.9% vs. 9.8%, p = 0.03). |

| Druss et al. [31] USA | RCT | (1) Adults with a Serious mental illness. (2) Having a cardiometabolic risk factor: hypertension, hyperglycemic; cholesterol level >240 mg/dL and low-density lipo-protein (LDL) level >160 mg/dL (n = 447). | (1) The behavioral health home at a CMHS provided care for cardiometabolic risk factors and comorbid medical problems and included: (a) staff assignment (nurse with prescribing authority, nurse care manager); (b) weekly supervision meetings; (c) health education for lifestyle; (d) support patients to attend their medical appointments; (e) staff attended weekly rounds at the CMHC. (2) Duration: 12 months; comparison: TAU. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) health care utilization and quality of care; (b) quality indicators for management of cardiometabolic risk factors. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) blood samples (fasting blood levels of glucose; fractionated cholesterol, HbA1c); (b) Framingham risk score; (c) 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36); (d) patient activation. | (1) Primary outcomes: intervention showed significant differences compared to TAU on different domains: (a) the proportion of services received (67% to 81% vs. 65% to 63% in TAU; p < 0.001); (b) improvement of diabetes care (38% to 63% vs. 41% to 44% in TAU; p < 0.001); (c) quality of medication treatment (diabetic (81.0% vs. 67%; p = 0.04) and hypertension (92% vs. 75%; p < 0.01)); (d) improvement in prevention services (36% to 56% vs. 36% to 33% in TAU; p < 0.001); and (e) primary care visits increased compared to TAU (p < 0.001). (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) fasting blood levels of glucose; fractionated cholesterol and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c); and (b) the SF-36 showed a significant improvement on both mental (29.9–38; p < 0.001) and physical component (40.5–42.9, p = 0.003) in the intervention group at 12 months follow-up but was not significant in comparison with the control group. |

| Druss et al. [23] USA | Group RCT | (1) Adults with a SMI. (2) Having a chronic general physical illness (n = 400). | (1) The Health and Recovery Peer intervention is a peer-led program for self-management: (a) a six-session program for persons with a SMI; (b) led by two certified peer specialists; (c) one-on-one peer coaching contacts were made; (d) four trained certified peer specialists functioned as interventionists. (2) Duration of the intervention: six months; comparison: TAU | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) Health Related Quality of Life (SF-36). (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) medication self-management; (b) medication self-assessment; (c) Patient Activation Measure; (d) assessment of diet; (e) Morisky Medication Adherence Scale; (f) Primary Care Contacts and (g) Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS). | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) SF-36: participants in the intervention group improved significantly on both the physical component and the mental health component compared to TAU (PCS: 2.7% vs. 1.4%; p = 0.46; d = 0.11); (MCS: 4.6% vs. 2.5%; p = 0.039; d = 0.17). (2) Secondary outcomes: significant differences between control and intervention group were found in: (a) RAS: At six-month (0.15% points in intervention group versus 0.08%, p = 0.02); (b) Patient Activation Measure: significant increase in the intervention group (+3.1 points vs. +1.5 in TAU, p = 0.01). |

| Gaughran et al. [32] UK | RCT | (1) Aged between 18 and 65 years with diagnosis of psychotic disorder. | An Integrated Health Promotion intervention: “IMPaCT therapy”: (a) implemented by patient’s usual caregivers after IMPACT-training and Physical Health awareness. (2) Duration: 9-months; comparison: TAU. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) SF-36. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) physical health measures; (b) substance use; (c) lifestyle measures diet, physical activity; (d) mental health status. | (1) SF-36: (a) no significant treatment effect for Physical or Mental health scores between TAU and IMPACT; (b) effects on physical health (d = −0.17 (12 months) and −0.09 (15 months)); mental health, (d= 0.03 (12 months) and −0.05 (15 months)). (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) significant difference in HDL cholesterol intervention; (b) reduction in waist circumference compared to control (−4.20 cm, p = 0.006). |

| Goldberg et al. [33] USA | RCT | (1) Adults with diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder with psychotic elements. (2) At least one chronic general medical condition (n = 63). | Goal of this study is to implement collaborative care to enhance patients’ self-management by structured collaborative practices: (a) a team that consists minimally of a nurse, patient, and psychiatrist, and possibly a family member; (b) treatment plan. | Primary outcomes: (a) SF-12 was used to assess global functioning and Quality of Life; (b) the 6-item Self-Management Self-Efficacy Scale: (c) the 13- item Patient Activation Scale; (d) the 18-item Multidimensional Health Locus of Control; (e) the 24-item Recovery Assessment Scale–Short Form; (f) 18-item Instrument to Measure Self-Management; and (g) the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale | (1) Primary outcomes: (a)The 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12), (b) Self-Management Self-Efficacy Scale, (c) the 13- item Patient Activation Scale showed statistically significant improvements in favor of the control group at post-intervention. At follow-up, however, none of these differences were significant. |

| Gutiérrez-Rojas et al. [34] Spain | Quasi–experimental | (1) Adults diagnosed with schizophrenia. (2) Being overweight (BMI+25). (3) Enrolled in community mental health center (n = 403). | (1) Determine the effectivity of basic screening for cardiovascular risk and Metabolic Syndrome (MS) combined with counselling: (a) for contacts over a period of 12-months; (b) during contacts participants were informed and information pamphlets were distributed.Comparison: baseline data at 12-month follow-up. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) blood samples (cholesterol, glucose); (b) symptoms (PANSS); (c) waist circumference; (d) weight; (e) Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Score. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) Global functioning: GAF-score; (b) Health related Quality of life: EQ-5D. | (1) Primary outcomes: Significant results were found for: (a) blood samples (blood glucose (mg/dL) (103.1 vs. 99.2, p = 0.0034); total cholesterol (mg/dL) (219.9 vs. 211.5, p < 0.0001); hdL Cholesterol (mg/dl) (47.5 vs. 49.5, p = 0.02); LdL Cholesterol (mg/dL) (139.7 vs. 132.9, p = 0.0023); triglycerides (mg/dL) (174.1 vs. 161.1, p = 0.0005)); (b) symptoms (PANSS score decreased significantly, (80.7 vs. 69.7; p < 0.001; (c) waist circumference (113.0 vs. 110.7, p < 0.0001) and (d) weight (93.4 vs. 91.4, p < 0.0001) decreased significantly; (e) the Framingham CVD risk score (vs. 7.8 p = 0.0353) also decreased. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) GAF score showed significant improvement at the end of the study (52.7 vs. 60.3 p < 0.0001); (b) EQ-5D significantly increased (59.4 and 66.8, p < 0.001). |

| Kelly et al. [27] USA | RCT | (1) Adults diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression. | The “Bridge” intervention is: (a) a manualized intervention that uses motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral strategies and psychoeducation; (b) is personalized to the healthcare experiences and needs of the participant; (c) aims to increase access, experience and self-management regarding healthcare; (d) facilitated by trained peer health navigators; (e) three peer health navigators had caseloads of about 20 each throughout the study. (2) Duration of intervention: 6-months; comparison: TAU. | (1) Outcomes: (a) the Working Alliance Inventory; (b) intervention fidelity and intensity; (c) health service utilization (‘UCLA CHIPTS healthcare’ and ‘health utilization survey’); (d) satisfaction with primary care provider (Engagement with the Healthcare Provider Scale); (e) self-management attitudes and behaviors; (f) checklist of 10 chronic health diagnoses; SF-12. | (1) Outcomes: (a) the intervention group reported higher quality relationships with their primary care providers; (b) intervention fidelity scores were above the “good” range; (c) health service utilization showed a trend for more routine health screenings in the treated group, and they also increased their visits to routine care providers more than the TAU group; (d) in Chi-square comparisons, the intervention group was significantly more likely to stay connected or become connected to primary care (80%) than those in the waitlist group (63%); (e) a checklist of 10 chronic health diagnoses: the intervention led to higher rates of diagnoses for the treatment group compared to the waitlist group; (f) significant reductions in the severity of bodily pain were reported by those in the treated group compared to the waitlisted TAU group. |

| Kilbourne et al. [22] USA | RCT | (1) Adults with diagnosis of bipolar disorder. (2) Presence of cardio-vascular risk factor; dyslipidemia; diabetes mellitus; obesity (BMI > 30); diagnosis of arteriosclerotic CVD (n = 118). | (1) Life Goals Collaborative Goals-program (LGCC): (a) self-management support; (b) care management: monthly follow-up, medical support; (c) guideline support to the caregivers involved. (2) Duration: 24 months; comparison: enhanced TAU. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) physical health measures, (b) quality of life (SF-12). (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) HDL and LDL-levels; (b) BMI; (c) waist circumference; (d) Framingham Risk score; (e) additional outcomes. | (1) Primary outcomes: no significant effects for all primary outcomes (blood pressure; total cholesterol; SF-12). (2) Secondary outcomes: LGCC-arm showed reduced manic symptoms over the 24-month period (p = 0.01). |

| Kilbourne et al. [21] USA | RCT | (1) Adults with diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. (2) Presence of cardiovascular risk factor; dyslipidemia | (1) Life Goals Collaborative Care (LGCC): (a) five Self-management group sessions guided by trained educator; (b) Monthly Care Management calls to increase follow-up; (c) shared care-plans with caregivers. (2) Duration: 12 months; comparison: TAU. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) quality of life (VR-12); (b) cardiovascular risk (blood pressure; BMI; physical activity (IPAQ-SF). (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) mental health symptoms; (b) Framingham Risk Score. | (1) In favor of the intervention there was a: (a) greater improvement on VR-12 physical health component scores (p = 0.01); significant reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (p = 0.04). (2) No significant difference in Framingham Risk Scores. |

| Meepring et al. [24] Thailand | Quasi–experimental | (1) Aged between 18 and 65 years, diagnosis of a SMI Exclusion: actively being treated for primary substance abuse (n = 105). | (1) The Health and Improvement Profile HIP was modified to the context of Thailand (HIP-T): (a) 10 Mental health Nurses were recruited; (b) the MHNs received a three-hour HIP-T training workshop. Comparison: baseline at 12-month follow-up. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) BMI, (b) blood pressure. (2) Secondary outcome: (a) patient self-reported health behavior and potential health risks. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) BMI showed a significant decrease (mean, 0.78/m2; p < 0.001); (b) significant decrease in weight (mean −1.13 kg; p < 0.001). (2) Secondary outcome: (a) results showed significant reductions in the number of participants with a red-flagged BMI at 12-months (p = 0.039) (pulse (p = 0.001), feet check (p = 0.004), sleep (p = 0.008), and self-checking of breasts (p = 0.002)); (b) a decrease of the total red flagged items for physical health pre and post-intervention (335, mean 3,19, (SD = 2.6) vs. 244, mean 2.32 (SD = 2.1), p < 0.001). |

| Rogers et al. [35] USA | RCT | (1) Adults having a serious mental illness. (2) Receiving mental health services as usual (n = 200). | (1) Min. three contacts with nurse practitioner (NP) who was situated at a CMHC: coordinated healthcare; complementary primary healthcare; address issues related to psychiatric condition; lifestyle, nutrition and exercise counseling; facilitate access to specialty care. (2) The NP followed guidelines including health assessment, diagnosis, and planning and was supervised by a physician in the community. Comparison: TAU with monthly educational sessions. | Outcomes: (a) SF-36 Quality of Life; (b) treatment outcome package (functioning, physical and mental health; (c) Multi-dimensional Health Locus of Control Form; (d) health beliefs; (e) The Primary Care Assessment Tool (PCAT) perceived quality of primary healthcare; (f) Nutrition, Prevention and Exercise Questions. | (1) Outcomes: (a) PCAT: Continuity of Care (p = 0.04) and the community orientation of the primary care provider (p = 0.05) showed significant differences favoring the intervention; (b) SF-36: social functioning increased more in the TAU-group compared to the High Exposure group (p = 0.01) |

| Sajatovic et al. [36] USA | RCT | (1) Adults with SMI (schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder). (2) Comorbid type 2 diabetes (n = 200). | (1) Targeted Training in Illness Management (TTIM): (a) group-based psychosocial treatment; (b) educational support by nurses; and (c) social support and communication through peers. (2) Duration: 60 weeks; comparison: TAU | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) mental illness severity; (b) Global functioning (GAF); and (c) Health related Quality of Life (SF-36). (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) parameters linked to diabetes control (serum glycosylated hemoglobin, HbA1c); (b) knowledge of diabetes; | (1) Primary Outcomes: (a) psychiatric symptoms improved significantly at 60-week follow-up among TTIM versus treatment-as-usual participants; (b) improvement on GAF-score was significantly greater in the TTIM group vs. TAU; (c) SF-36 showed no significant group differencesHbA1c. (2) Secondary Outcomes: (a) HbA1c showed no significant differences, (b) diabetes knowledge improved significantly for TTIM versus treatment as usual (p < 0.001). |

| Speyer et al. [37] Jakobsen et al. [26] Denmark | Randomized, parallel-group Trial | (1) Adults with diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or persistent delusional disorder (ICD-10). (2) A waist circumference above 88 cm for women and 102 cm for men (n = 428). | Participants receive TAU alone or combined with lifestyle coaching or care coordination: (1) lifestyle coaching: (a) a manual-based intervention; (b) lifestyle coach offered home visits in daily life; (c) personal and professional networks were included; (d) patients could have contact with the team member for one year; (e) coach to participant ratio was 1:15. (2) Care coordination: (a) manual-based intervention; (b) a trained psychiatric nurse facilitated contact with primary care; (c) the coordinator to participant ratio was 1:40. (3) Duration of the study: 12-month follow-up (Speyer) and 24-month follow-up (Jakobsen). Comparison: TAU. | (1) Primary outcome: (a) Copenhagen Risk Score: the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) cardio-respiratory fitness; (b) physical and lifestyle measures; (c) delf-reported physical activity (Physical Activity Scale); and (d) Quality of Life (MaNSA; EQ-5D). | Speyer (2016), at 12-month follow-up. (1) Primary outcomes: (a) The mean age-standardized 10-year risk of CVD was not significant. (2) Secondary outcomes: (a) no significant differences were found for any of the secondary outcomes. Jakobsen (2019), at 24 month follow-up. (1) Primary outcomes: the mean age-standardized 10-year risk of CVD showed a significant difference in sensitivity analyses of complete cases: the CVD risk was 9.0% (SD 5.9%) in the CHANGE group, 8.1% (SD 6.0%) in the care coordination group, and 7.8% (SD 6.1%) in the treatment as usual group (p = 0.08). (2) Secondary Outcomes: no significant differences were found for any of the secondary or exploratory outcomes. |

| Van Der Voort et al. [25] The Netherlands | Controlled trial | (1) Aged 18–65 years, diagnosis of bipolar disorder. | (1) Goal is to enhance patients’ self-management by structured collaborative practices: (a) a team (nurse, patient, and psychiatrist) (b) formulates a treatment plan and (c) offers psycho-education, (d) problem solving therapy, (e) mood charting, (f) early warning signs and (g) psycho-pharmacological and somatic care. (2) Duration of the intervention: 12-months. Comparison: TAU. | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) Global functioning: FAST-test; (b) Quality of Life (WHO Qol Bref) | (1) Primary outcomes: (a) Global functioning increased more in the intervention group compared to TAU (d = 0.3, p = 0.001); (b) at sox-month follow-up autonomy increased significantly in the intervention group compared to control and increased even more at 12-month follow-up (d = 0.5); (c) No significant differences were found in global Quality of Life; however, in the intervention group there was a significant increase for the physical health component. |

| Author | Weight (kg) | BMI | HbA1c (%) | Blood Glucose (mg/dL) | Cardiovascular Risk | LDL (mg/dL) | Number of Screening Visits | Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | Systolic BP (mmHg) | Diastolic BP (mmHg) | QOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation of Organizational models of care | |||||||||||

| Cameron et al. [21] | / | / | / | / | Screening cardiac enzymes: 1.1 vs. 0.7 per 100 inhabitants | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Druss et al. [23] | / | / | / | / | Framingham CRS7.8 (5.7)–6.9 (5.3) * | / | / | / | / | / | SF-36: Mental component:36.4 (10.1)-39.3 (9.91) * Physical component:36.4 (11.7)-37.1 (11.5) |

| Druss et al. [24] | / | / | 6.4 (2.2)– 6.5 (1.6) * | 113.7 (40.0)–111.9 (41.2) | Framingham CRS 10.4 (8.3)–9.2 (7.8) * | 122.9 (40.7)–112.2 (39.5) * | / | 202.6 (44.2)–193.8 (43.8) * | 137.0 (19.6)–132.1 (17.3) * | 89.5 (13.2)–83.6 (10.9) * | SF-36: Mental component: 29.9 (13.5)–38.0 (14.3) * Physical component: 40.5 (11.9)–42.9 (12.2) * |

| Gutiérrez-Rojas et al. [28] | 93.4 (17.9)–91.4 (18.1) * | 32.8 (5.1)–32.1 (5.3) * | / | 103.1 (26.5)–99.2 (21.0) * | Framingham CRS: 8.4 (95% CI = 7.4–9.41)-7.8 (95%CI = 6.93–8.75) * | 139.7 (42.5)–132.9 (36.5) * | / | 219.9 (47.5)–211.5 (42.1) * | 78.8 (10.8)–79.2 (9.9) | ||

| Rogers et al. [33] | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | SF-36: No significant findings |

| Van Der Voort et al. [37] | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | WHOQoLBref: Physical component: 54.4 (16.2)–56.5 (18.0) * Overall Score: 3.3 (1.0)–3.4 (0.8) |

| Formal training healthcare workers | |||||||||||

| Druss et al. [23] | / | / | / | / | Framingham CRS 7.8 (5.7)–6.9 (5.3) * | / | / | / | / | / | SF-36: Mental component:36.4 (10.1)–39.3 (9.91) * Physical component:36.4 (11.7)–37.1 (11.5) |

| Chwastiak et al. [28] | / | (−1.0 (CI:95%: −1.8; −0.1)) * | (−1.10 (CI:95%: −2.20; −0.01)) * | / | / | (−19.4 (CI:95%:−55.20; −16.5)) | / | / | (−1.10 (CI:95%:−14.3; −12.0)) | / | / |

| Gaughran et al. [26] | / | 30.63 (7.52)–30.04 (7.67) | (−0.32 (CI:95%; −1.49–0.86)) | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | SF-36: Mental component: 42.8 (13.73)–42.3 (13.42) Physical component: 47.44 (11.32)–47.54 (11.14) |

| Kilbourne et al. [30] | / | 32.0 (6.2)–31.3 (5.8) | / | / | Framingham CRS 12.4 (8.9)–11.5 (6.4) | 103.8(30.4)–105.6(39.5) | / | 176.9 (37.2)–178.9 (45.5) | 131.8 (16.4)–127.2 (15.4) * | 80.7 (11.4)–75.9 (10.4) * | SF-12: Mental component: 32.7(7.7)–34.9(7.5) Physical component: 35.9 (7.2)–36.8 (6.6) |

| Kilbourne et al. [31]) | / | 34.01 (6.74)–34.07 (6.98) * | / | / | Framingham CRS 12.6 (7.7)–12.8 (8.7) | 112.24 (35.52)–107.71 (34.18) * | / | 182.65 (42.32)–179.47 (41.70) | 135.39 (14.36)–135.95 (17.23) | 76.44 (8.74)–75.46 (9.05) | VR-12:Mental component: 35.42 (12.23)–38.13 (12.41) Physical component: 32.41 (10.59)–33.61 (11.36) * |

| Meepring et al. [32] | 63.9 (11.9)-62.8 (10.3) * | 22.8 (4.1)–22.0 (2.8) * | / | / | / | / | / | / | 115.1 (13.5)–116.6 (13.1) | 72.8 (8.5)–75.2 (9.0) * | / |

| Speyer et al. [35] | 103.1 (23.8) vs. 102.9 (21.7) | 33.9 (5.9) vs. 34.4 (6.3) | 5.6 (3) vs. 5.4 (2.1) * | / | Copenhagen risk score: 8.4 (6.7) vs. 8.1 (6.5) | / | / | / | 128.7 (13.9) vs. 129.1 (14.1) | / | EuroQOL 1.4 (0.3) vs. 1.3 (0.3) |

| Jakobsen et al. [36] | 105.9 (22.2) vs. 104.9 (22.1) | 35.6 (8.6) vs. 34.4 (8.6) | 5.5 (2.4) vs. 5.4 (2.4) | / | Copenhagen risk score: 8.7 (6.0) vs. 8.0 (6.3) | / | / | / | 129.1 (13.0) vs. 128.3 (13.4) | / | MANSA score: 4.8 (0.1) vs. 4.9 (0.1) |

| Educational or Coaching Interventions | |||||||||||

| Druss et al. [25] | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | SF-36:Mental component: 32.05 (11.8)–36.64 (12.3) * Physical component: 32.73 (10.9)–35.42 (11.0) |

| Goldberg et al. [27] | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | SF-12: No significant changes at follow-up |

| Kelly et al. [27] | / | / | / | / | / | / | 0.92 (0.92)–1.20 (0.99) * | / | / | / | / |

| Sajatovic et al. [34] | / | 35.44 (8.0)–36.46 (8.6) | 8.0 (2.2)–7.69 (1.9) | / | / | / | / | / | 134.99 (20.7)–134.12 (20.7) | / | SF-36:Mental component: 37.17 (10.6)–42.05 (11.1)Physical component: 39.38 (10.1)–39.65 (11.1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martens, N.; Destoop, M.; Dom, G. Organization of Community Mental Health Services for Persons with a Severe Mental Illness and Comorbid Somatic Conditions: A Systematic Review on Somatic Outcomes and Health Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020462

Martens N, Destoop M, Dom G. Organization of Community Mental Health Services for Persons with a Severe Mental Illness and Comorbid Somatic Conditions: A Systematic Review on Somatic Outcomes and Health Related Quality of Life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020462

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartens, Nicolaas, Marianne Destoop, and Geert Dom. 2021. "Organization of Community Mental Health Services for Persons with a Severe Mental Illness and Comorbid Somatic Conditions: A Systematic Review on Somatic Outcomes and Health Related Quality of Life" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020462

APA StyleMartens, N., Destoop, M., & Dom, G. (2021). Organization of Community Mental Health Services for Persons with a Severe Mental Illness and Comorbid Somatic Conditions: A Systematic Review on Somatic Outcomes and Health Related Quality of Life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020462