Association between Improvement of Oral Health, Swallowing Function, and Nutritional Intake Method in Acute Stroke Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

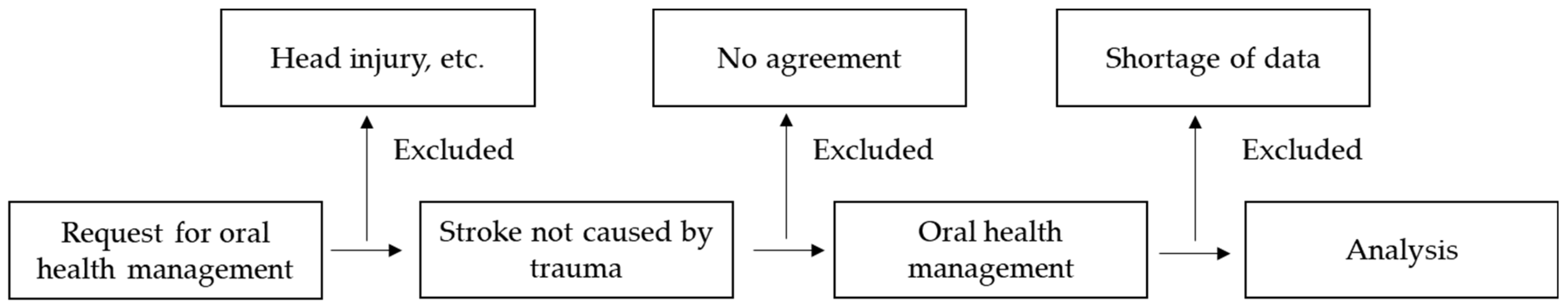

2.1. Research Participants

2.2. Basic Patient Information

2.3. Evaluation Elements in the First Assessment and at Discharge

2.4. Classification According to Nutritional Intake at the Time of Hospital Discharge

2.5. Factors That Influence the Improvement of Nutritional Intake Methods

2.6. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Basic Participants Characteristics

3.2. Comparison of the Tube Feeding Group and the Oral Feeding Group at Discharge

3.3. Factors Associated with the Improvement of Nutritional Intake Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of the Characteristics of the Participants According to Different Methods of Nutritional Intake at Discharge

4.2. Comparison of Systemic and Oral Items Using Different Nutritional Intake Methods

4.3. Factors Influencing the Improvement of Nutritional Intake Methods

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, R.; Lam, O.L.; Lo, E.C.; Li, L.S.; Wen, Y.; McGrath, C. Orofacial functional impairments among patients following stroke: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.K.; Jang, S.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.K. Effect of an oral hygiene care program for stroke patients in an intensive care unit. Yonsei Med. J. 2014, 55, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Takahata, H.; Tsutsumi, K.; Baba, H.; Nagata, I.; Yonekura, M. Early intervention to promote oral feeding in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2011, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aoki, S.; Hosomi, N.; Hirayama, J.; Nakamori, M.; Yoshikawa, M.; Nezu, T.; Kubo, S.; Nagano, Y.; Nagao, A.; Yamane, N.; et al. The multidisciplinary swallowing team approach decreases pneumonia onset in patients with acute stroke. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yellowitz, J.A.; Schneiderman, M.T. Elder’s oral health crisis. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2014, 14, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhorne, P.; Stott, D.J.; Robertson, L.; MacDonald, J.; Jones, L.; McAlpine, C.; Dick, F.; Taylor, G.S.; Murray, G. Medical complications after stroke: A multicenter study. Stroke 2000, 31, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, K.C.; Li, J.Y.; Lyden, P.D.; Hanson, S.K.; Feasby, T.E.; Adams, R.J.; Faught, R.E., Jr.; Haley, E.C., Jr. Medical and neurological complications of ischemic stroke: Experience from the RANTTAS trial. RANTTAS Investigators. Stroke 1998, 29, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kikuchi, R.; Watabe, N.; Konno, T.; Mishina, N.; Sekizawa, K.; Sasaki, H. High incidence of silent aspiration in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994, 150, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithard, D.G.; O’Neill, P.A.; Parks, C.; Morris, J. Complications and outcome after acute stroke: Does dysphagia matter? Stroke 1996, 27, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, G.; Hankey, G.J.; Cameron, D. Swallowing function after stroke: Prognosis and prognostic factors at 6 months. Stroke 1999, 30, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finestone, H.M.; Greene-Finestone, L.S.; Wilson, E.S.; Teasell, R.W. Malnutrition in stroke patients on the rehabilitation service and at follow-up: Prevalence and predictors. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995, 76, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávalos, A.; Ricart, W.; Gonzalez-Huix, F.; Soler, S.; Marrugat, J.; Molins, A.; Suñer, R.; Genís, D. Effect of malnutrition after acute stroke on clinical outcome. Stroke 1996, 27, 1028–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, P.; Laffond, T.; Campos, S.; Dupuis, V.; Bourdel-Marchasson, I. Relationships between oral health, dysphagia and undernutrition in hospitalised elderly patients. Gerodontology 2016, 33, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuya, J.; Suzuki, H.; Hidaka, R.; Akatsuka, A.; Nakagawa, K.; Yoshimi, K.; Nakane, A.; Shimizu, Y.; Saito, K.; Itsui, Y.; et al. Oral health status and its association with nutritional support in malnourished patients hospitalised in acute care. Gerodontology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnaby, G.; Hankey, G.J.; Pizzi, J. Behavioural intervention for dysphagia in acute stroke: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenaga, Y.; Nakayama, S.; Taniguchi, H.; Ohori, I.; Komatsu, N.; Nishimura, H.; Katsuki, Y. Factors predicting recovery of oral intake in stroke survivors with dysphagia in a convalescent rehabilitation ward. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 26, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, S.; Inamoto, Y.; Oguchi, K.; Kondo, T.; Otaka, E.; Mukaino, M.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, M.; Saitoh, E. Outcomes of dysphagia following stroke: Factors influencing oral intake at 6 months after onset. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 16, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuya, J.; Suzuki, H.; Tamada, Y.; Onodera, S.; Nomura, T.; Hidaka, R.; Minakuchi, S.; Kondo, H. Food intake and oral health status of inpatients with dysphagia in acute care settings. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obana, M.; Furuya, J.; Matsubara, C.; Tohara, H.; Inaji, M.; Miki, K.; Numasawa, Y.; Minakuchi, S.; Maehara, T. Effect of a collaborative transdisciplinary team approach on oral health status in acute stroke patients. J. Oral Rehabil. 2019, 46, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Respiratory Society. The JRS Guidelines for the Management of Pneumonia in Adults; The Japanese Respiratory Society: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, G.; Jennett, B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: A practical scale. Lancet 1974, 2, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.; Godwin, J.; Richards, S.; Warlow, C. The United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TIA) aspirin trial: Final results. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1991, 54, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crary, M.A.; Mann, G.D.; Groher, M.E. Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005, 86, 1516–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.; Saitoh, E.; Okada, S. Dysphagia rehabilitation in Japan. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 19, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, K.; Kagaya, H.; Shibata, S.; Onogi, K.; Inamoto, Y.; Ota, K.; Miki, T.; Tamura, S.; Saitoh, E. Accuracy of Dysphagia Severity Scale rating without using videoendoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Jpn. J. Compr. Rehabil. Sci. 2015, 6, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, J.M.; King, P.L.; Spencer, A.J.; Wright, F.A.; Carter, K.D. The oral health assessment tool--validity and reliability. Aust. Dent. J. 2005, 50, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miyazaki, H.; Shirahama, R.; Ohtani, I.; Shimada, N.; Takehara, T. Oral health conditions and denture treatment needs in institutionalized elderly people in Japan. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1992, 20, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finegold, S.M. Aspiration pneumonia. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1991, 13, S737–S742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, P.C.; Lee, A.H.; Binns, C.W. High incidence of respiratory infections in ‘nil by mouth’ tube-fed acute ischemic stroke patients. Neuroepidemiology 2009, 32, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, S.J.; Huang, K.Y.; Wang, T.G.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, C.H.; Tang, S.C.; Tsai, L.K.; Yip, P.K.; Jeng, J.S. Dysphagia screening decreases pneumonia in acute stroke patients admitted to the stroke intensive care unit. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 15, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, K.; Koga, T.; Akagi, J. Tentative nil per os leads to poor outcomes in older adults with aspiration pneumonia. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Chróinín, D.; Montalto, A.; Jahromi, S.; Ingham, N.; Beveridge, A.; Foltyn, P. Oral health status is associated with common medical comorbidities in older hospital inpatients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 1696–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jönsson, A.C.; Lindgren, I.; Norrving, B.; Lindgren, A. Weight loss after stroke: A population-based study from the Lund Stroke Register. Stroke 2008, 39, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Romeo, J.; Wärnberg, J.; Pozo, T.; Marcos, A. Physical activity, immunity and infection. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marshall, S.; Young, A.; Bauer, J.; Isenring, E. Malnutrition in geriatric rehabilitation: Prevalence, patient outcomes, and criterion validity of the scored patient-generated subjective global assessment and the mini nutritional assessment. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abd Aziz, N.; Mohd Fahmi Teng, N.I.; Kamarul Zaman, M. Geriatric Nutrition Risk Index is comparable to a mini nutritional assessment for assessing nutritional status in elderly hospitalized patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 29, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, W.J.; Whiting, S.J.; Tyler, R.T. Protein content of puréed diets: Implications for planning. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2007, 68, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, L.; Cotter, D.; Hickson, M.; Frost, G. Comparison of energy and protein intakes of older people consuming a texture modified diet with a normal hospital. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2005, 18, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.M.; Hansen, K.S. Meals served in Danish nursing homes and to Meals-on-Wheels clients may not offer nutritionally adequate choices. J. Nutr. Elder 2010, 29, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, M.; Yamashita, Y. Oral health and swallowing problems. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2013, 15, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamamoto, H.; Furuya, J.; Tamada, Y.; Kondo, H. Impacts of wearing complete dentures on bolus transport during feeding in elderly edentulous. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013, 40, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onodera, S.; Furuya, J.; Yamamoto, H.; Tamada, Y.; Kondo, H. Effects of wearing and removing dentures on oropharyngeal motility during swallowing. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, A.; Watanabe, R.; Nishimuta, M.; Hanada, N.; Miyazaki, H. The relationship between dietary intake and the number of teeth in elderly Japanese subjects. Gerodontology 2005, 22, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, M.; Suzuki, R.; Kikutani, T. Nutrition and oral status in elderly people. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2014, 50, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shiraishi, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Wakabayashi, H.; Tsuji, Y.; Shimazu, S.; Jeong, S. Impaired oral health status on admission is associated with poor clinical outcomes in post-acute inpatients: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2677–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kwon, S.U.; Yun, S.C.; Koh, J.Y.; Kang, D.W. Undernutrition as a predictor of poor clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakajoh, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Sekizawa, K.; Matsui, T.; Arai, H.; Sasaki, H. Relation between incidence of pneumonia and protective reflexes in post-stroke patients. J. Intern. Med. 2000, 247, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziewas, R.; Ritter, M.; Schilling, M.; Konrad, C.; Oelenberg, S.; Nabavi, D.G.; Stögbauer, F.; Ringelstein, E.B.; Lüdemann, P. Pneumonia in acute stroke patients fed by nasogastric tube. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2004, 75, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teasell, R.W.; Bach, D.; McRae, M. Prevalence and recovery of aspiration poststroke: A retrospective analysis. Dysphagia 1994, 9, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoefer, C.D.; Pepper, J.V.; Manski, R.J.; Moeller, J.F. Dental Care Use, Edentulism, and Systemic Health among Older Adults. J. Dent. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level 1 | Tube-dependent (including intravenous feeding) and nothing by mouth. |

| Level 2 | Tube-dependent with minimal attempts of food or liquid intake. |

| Level 3 | Tube-dependent with consistent oral intake of food or liquid. |

| Level 4 | Total oral diet of a single consistency. |

| Level 5 | Total oral diet with multiple consistencies, but requiring special preparation or compensation. |

| Level 6 | Total oral diet with multiple consistencies without special preparation, but with specific food limitations. |

| Level 7 | Total oral diet with no restrictions. |

| Tube-Feeding Group (N = 68) | Oral Nutrition Group (N = 148) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 25% | 50% | 75% | N | % | Mean ± SD | 25% | 50% | 75% | N | % | p | Test | ||

| Age, | years | 67.7 ± 13.4 | 60.0 | 70.0 | 78.8 | 68 | 61.9 ± 15.5 | 49.0 | 63.0 | 74.0 | 148 | 0.008 ** | a | ||

| Sex, | |||||||||||||||

| Male, | n | 43 | 63.2 | 88 | 59.5 | 0.598 | b | ||||||||

| Female, | n | 25 | 36.8 | 60 | 40.5 | ||||||||||

| Primary disease, | |||||||||||||||

| Brain infarct, | n | 20 | 29.4 | 50 | 33.8 | 0.524 | b | ||||||||

| Brain hemorrhage, | n | 28 | 41.2 | 50 | 33.8 | 0.293 | b | ||||||||

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage, | n | 21 | 30.9 | 50 | 33.8 | 0.673 | b | ||||||||

| Coexisting disease, | % | 56 | 82.4 | 115 | 77.7 | 0.434 | b | ||||||||

| Stroke-related surgical procedures, | % | 51 | 75.0 | 99 | 66.9 | 0.230 | b | ||||||||

| Aspiration pneumonia, | % | 34 | 50.0 | 22 | 14.9 | <0.001 ** | b | ||||||||

| Duration of hospitalization, | days | 56.0 ± 33.0 | 30.5 | 54.0 | 72.5 | 68 | 35.6 ± 19.1 | 22.0 | 32.0 | 46.8 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| Number of oral health management, | count | 10.8 ± 7.9 | 4.0 | 9.5 | 16.8 | 68 | 5.3 ± 3.6 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| Number of present teeth, | teeth | 20.6 ± 8.7 | 14.0 | 24.0 | 28.0 | 68 | 21.2 ± 9.5 | 16.3 | 26 | 28 | 148 | 0.268 | a | ||

| Number of functional teeth, | teeth | 20.9 ± 8.9 | 14.0 | 24.5 | 28.0 | 68 | 25.2 ± 5.8 | 25.0 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| GCS, | level | 5.9 ± 4.2 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 68 | 11.57 ± 4.06 | 9.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| mRS, | score | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 68 | 4.24 ± 1.25 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| OHAT total score, | score | 4.9 ± 3.1 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 6.8 | 68 | 4.5 ± 2.7 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 148 | 0.532 | a | ||

| DSS, | level | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 68 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| Alb, | g/dL | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 68 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| CRP, | mg/L | 5.9 ± 5.2 | 1.3 | 4.1 | 10.0 | 68 | 3.1 ± 4.4 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 4.1 | 148 | <0.001 ** | a | ||

| Tube-Feeding Group (N = 68) | Oral Nutrition Group (N = 148) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | 25% | 50% | 75% | Mean ± SD | 25% | 50% | 75% | p | ||

| GCS, | level | 8.8 ± 4.1 | 5.0 | 9.0 | 12.0 | 14.4 ± 1.3 | 14.3 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 0.003 ** |

| mRS, | score | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | <0.001 ** |

| OHAT total score, | score | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.4 ± 1.9 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | <0.001 ** |

| DSS, | level | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 7.0 | <0.001 ** |

| Alb, | g/dL | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.8 | <0.001 ** |

| CRP, | mg/L | 3.3 ± 5.6 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 4.5 | 1.5 ± 2.6 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.001 ** |

| p | Odds Ratio | (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, | Years | 0.866 | 1.003 | 0.97–1.04 |

| Sex | 0:male, 1:female | 0.627 | 0.788 | 0.30–2.06 |

| Duration of hospitalization | Days | 0.924 | 0.999 | 0.97–1.02 |

| Number of teeth present | Teeth | 0.076 | 0.949 | 0.90–1.01 |

| Number of functional teeth | teeth | 0.040 * | 1.087 | 1.00–1.18 |

| Number of oral health management interventions | count | 0.783 | 0.984 | 0.88–1.11 |

| Improvement level of GCS | score | 0.620 | 0.962 | 0.82–1.12 |

| Improvement level of DSS | score | <0.001 ** | 7.441 | 3.95–14.00 |

| Stroke-related surgical procedures | 0:not available, 1:available | 0.788 | 1.146 | 0.42–3.10 |

| Improvement level of the total OHAT score | score | 0.048 * | 1.226 | 1.00–1.50 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 0:not available, 1:available | 0.871 | 0.923 | 0.35–2.43 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aoyagi, M.; Furuya, J.; Matsubara, C.; Yoshimi, K.; Nakane, A.; Nakagawa, K.; Inaji, M.; Sato, Y.; Tohara, H.; Minakuchi, S.; et al. Association between Improvement of Oral Health, Swallowing Function, and Nutritional Intake Method in Acute Stroke Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111379

Aoyagi M, Furuya J, Matsubara C, Yoshimi K, Nakane A, Nakagawa K, Inaji M, Sato Y, Tohara H, Minakuchi S, et al. Association between Improvement of Oral Health, Swallowing Function, and Nutritional Intake Method in Acute Stroke Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111379

Chicago/Turabian StyleAoyagi, Michiyo, Junichi Furuya, Chiaki Matsubara, Kanako Yoshimi, Ayako Nakane, Kazuharu Nakagawa, Motoki Inaji, Yuji Sato, Haruka Tohara, Shunsuke Minakuchi, and et al. 2021. "Association between Improvement of Oral Health, Swallowing Function, and Nutritional Intake Method in Acute Stroke Patients" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111379

APA StyleAoyagi, M., Furuya, J., Matsubara, C., Yoshimi, K., Nakane, A., Nakagawa, K., Inaji, M., Sato, Y., Tohara, H., Minakuchi, S., & Maehara, T. (2021). Association between Improvement of Oral Health, Swallowing Function, and Nutritional Intake Method in Acute Stroke Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111379