Moral Identity and Attitudes towards Doping in Sport: Whether Perception of Fair Play Matters

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Doping Attitudes

2.2.2. Moral Identity

2.2.3. Perception of Fair Play

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Comparison between Athletes and Non-Athletes

3.3. Main Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Athletes’ Moral Identity, Perception of Fair Play and Attitudes towards Doping

4.2. Non-Athletes’ Moral Identity, Perception of Fair Play, and Attitudes towards Doping

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Serrano-Durá, J.; Molina, P.; Martínez-Baena, A. Systematic review of research on fair play and sporting competition. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, P.; Úbeda-Colomer, J.; Valenciano, J. Justicia social y fair play. In Crisis, Cambio Social y Deporte; Llopis, R., Ed.; Nau Llibres: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 617–623. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, S.; Fortier, K. Comprehensive overview of the problem of violence against athletes in sport. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2018, 42, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.; Pope, H.G.; Cleret, L.; Petroczi, A.; Nepusz, T.; Schaffer, J.; Kanayama, G.; Comstock, R.D.; Simon, P. Doping in two elite athletics competitions assessed by randomized-response surveys. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Navarro, M.; Salinero, J.J.; Muñoz-Guerra, J.; Plata, M.D.M.; Del Coso, J. Sport-specific use of doping substances: Analysis of World Anti-Doping Agency Doping Control Tests between 2014 and 2017. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 55, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Navarro, M.; Munoz-Guerra, J.; Plata, M.; Del Coso, J. Analysis of doping control test results in individual and team sports from 2003 to 2015. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, F.; Altavilla, G.; D’elia, F.; Raiola, G. Development of doping in sports: Overview and analysis. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroczi, A.; Aidman, E. Measuring explicit attitude toward doping: Review of the psychometric properties of the performance enhancement attitude scale. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.; Kopp, M.; Niedermeier, M.; Schnitzer, M.; Schobersberger, W. Predictors of doping intentions, susceptibility, and behaviour of elite athletes: A meta-analytic review. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Ng, J.Y.; Barkoukis, V.; Backhouse, S. Personal and psychosocial predictors of doping use in physical activity settings: A meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 1603–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.J. Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.R.; Madigan, D.J.; Duncan, L.; Hallward, L.; Lazuras, L.; Bingham, K.; Fairs, L.R. Cheater, cheater, pumpkin eater: The Dark Triad, attitudes towards doping, and cheating behaviour among athletes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 20, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkoukis, V.; Brooke, L.; Ntoumanis, N.; Smith, B.; Gucciardi, D.F. The role of the athletes’ entourage on attitudes to doping. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2483–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberg, T.; Moston, S. Inside the locker room: A qualitative study of coaches’ anti-doping knowledge, beliefs and attitudes. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, K.; McKenna, J.; Backhouse, S.H. A qualitative analysis of the factors that protect athletes against doping in sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V.; Tsorbatzoudis, H. Toward an integrative model of doping use: An empirical study with adolescent athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchetti, G.; Candela, F.; Villosio, C. Psychological and social correlates of doping attitudes among Italian athletes. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Taylor, J.; Dimeo, P.; Dixon, S.; Robinson, L. Predicting elite Scottish athletes’ attitudes towards doping: Examining the contribution of achievement goals and motivational climate. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudrak, J.; Slepicka, P.; Slepickova, I. Sport motivation and doping in adolescent athletes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, K.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, K. Relationship between perfectionism and attitudes toward doping in young athletes: The mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, S.; Yousefi, B.; Kaviani, E.; Ariapooran, S. The prevalence of energetic drugs use and the role of perfectionism, sensation seeking and physical self-concept in discriminating bodybuilders with positive and negative attitude toward doping. Int. J. Sports Stud. 2014, 4, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, M.; Yoon, J.; Kang, H.; Kim, T. Influences of perfectionism and motivational climate on attitudes towards doping among Korean national athletes: A cross sectional study. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2017, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ommundsen, Y.; Roberts, G.C.; Lemyre, P.N.; Treasure, D. Perceived motivational climate in male youth soccer: Relations to social–moral functioning, sportspersonship and team norm perceptions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loland, S. Fair play. In Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Sport; McNamee, M., Morgan, W.J., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 333–350. [Google Scholar]

- Lucidi, F.; Zelli, A.; Mallia, L.; Nicolais, G.; Lazuras, L.; Hagger, M.S. Moral attitudes predict cheating and gamesmanship behaviors among competitive tennis players. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dovovan, R.J.; Egger, G.; Kapernick, V.; Mendoza, J. A conceptual framework for achieving performance enhancing drug compliance in sport. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucciardi, D.F.; Jalleh, G.; Donovan, R.J. An examination of the Sport Drug Control Model with elite Australian athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalleh, G.; Donovan, R.J.; Jobling, I. Predicting attitude towards performance enhancing substance use: A comprehensive test of the Sport Drug Control Model with elite Australian athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development; Kurtines, W.M., Gewirtz, J.L., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 45–103. [Google Scholar]

- Boardley, I.D.; Smith, A.L.; Mills, J.P.; Grix, J.; Wynne, C. Empathic and self-regulatory processes governing doping behavior. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ring, C.; Kavussanu, M. The role of self-regulatory efficacy, moral disengagement and guilt on doping likelihood: A social cognitive theory perspective. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, K.; Huang, T. Coaching style and attitudes toward doping in Chinese athletes: The mediating role of moral disengagement. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2017, 12, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, K.; Hargreaves, E.A.; Gerrard, D.; Lonsdale, C. Psychological mechanisms underlying doping attitudes in sport: Motivation and moral disengagement. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 35, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.A.; Elbe, A.-M.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A. Integrating moral and achievement variables to predict doping likelihood in football: A cross-cultural investigation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 47, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, C.; Kavussanu, M.; Lucidi, S.; Hurst, P. Effects of personal and situational factors on self-referenced doping likelihood. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 41, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanger, N.; Backhouse, S.H. A multistudy cross-sectional and experimental examination into the interactive effects of moral identity and moral disengagement on doping. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 42, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, K.; Reed, A. The self-importance of moral identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, K.; Freeman, D.; Reed, A.; Lim, V.K.G.; Felps, W. Testing a social cognitive model of moral behavior: The interaction of situational factors and moral identity centrality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavussanu, M.; Stanger, N.; Ring, C. The effects of moral identity on moral emotion and antisocial behavior in sport. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2015, 4, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Ring, C. Moral identity predicts doping likelihood via moral disengagement and anticipated guilt. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 39, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, H.; Lamprecht, M.; Kamber, M.; Marti, B.; Mahler, N. The public perception of doping in sport in Switzerland, 1995–2004. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchades, M.; Molina, P. Attitudes towards doping among sport sciences students. Apunt. Educ. Fís. y Deportes 2020, 140, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrunderbeek, H.; Tolleneer, J. Student attitudes towards doping in sport: Shifting from repression to tolerance? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2010, 46, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, H.A.; Hanstad, D.V.; Thøring, T.A. Doping in elite sport—do the fans care? Public opinion on the consequences of doping scandals. Int. J. Sport Mark. Spons. 2010, 11, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.R.; Madigan, D.J.; Levy, A.R. A confirmatory factor analysis of the performance enhancement attitude scale for adult and adolescent athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 28, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukys, S.; Karanauskiene, D. Adaptation and Validation of the Lithuanian-language version of the Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale (PEAS). J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 1430–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telama, R.; Naul, R.; Nupponen, H.; Rychtecky, A.; Vuolle, P. Physical Fitness, Sporting Lifestyles, and Olympic Ideals: Cross-Cultural Studies on Youth Sport in Europe; Hofmann: Schorndorf, Germany, 2002; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Majauskiene, D. Manifestation of Olympism and its Cohesion with School Culture and Prosocial Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, Lithuanian Sports University, Kaunas, Lithuania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Whitehead, J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A. Relationship among values, achievement orientations, and attitudes in youth sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkoukis, V.; Lazuras, L.; Tsorbatzoudis, H.; Rodafinos, A. Motivational and social cognitive predictors of doping intentions in elite sports: An integrated approach. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, e330–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Hurst, P.; Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M.; Galanis, E.; King, A.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Ring, C.A. Moral intervention reduces doping likelihood in UK and Greek athletes: Evidence from a cluster randomized trial. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 43, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, C.; Kavussanu, M.; Gürpınar, B.; Whitehead, J.; Mortimer, H. Basic values predict unethical behavior in sport: The case of athletes’ doping likelihood. Ethics Behav. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, H.; Lamprecht, M.; Kamber, M. Attitudes towards doping—A comparison of elite athletes, performance oriented leisure athletes and general population. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2014, 11, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bette, K.H.; Schimank, U. Doping in Hochleistungssport; Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- García-Grimau, E.; De la Vega, R.; De Arce, R.; Casado, A. Attitudes toward and susceptibility to doping in Spanish elite and national-standard track and field athletes: An examination of the Sport Drug Control Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, J.; Thrower, S.N.; Petróczi, A. Racing clean in a tainted world: A qualitative exploration of the experiences and views of clean British elite distance runners on doping and anti-doping. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 673087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Moral identity | 6.05 | 0.92 | 0.73 | |||

| 2. Perception of fair play | 3.07 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 0.24 ** | ||

| 3. Attitudes towards doping | 1.47 | 0.55 | 0.81 | −0.23 ** | −0.41 ** |

| Pathways | β | 95% CI | CSIE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects of moral identity on | ||||

| Attitude to doping | −0.14 *** | [−0.21. −0.06] | ||

| Perception of fair play | 0.11 *** | [0.05. 0.16] | ||

| Direct effect of perception of fair play on | ||||

| Attitude to doping | −0.51 *** | [−0.73. −0.32] | ||

| Indirect effect on attitudes to doping via | ||||

| Perception of fair play | −0.10 * | [−0.16. −0.04] | −0.09 * | [−0.17. −0.04] |

| Pathways | β | 95% CI | CSIE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

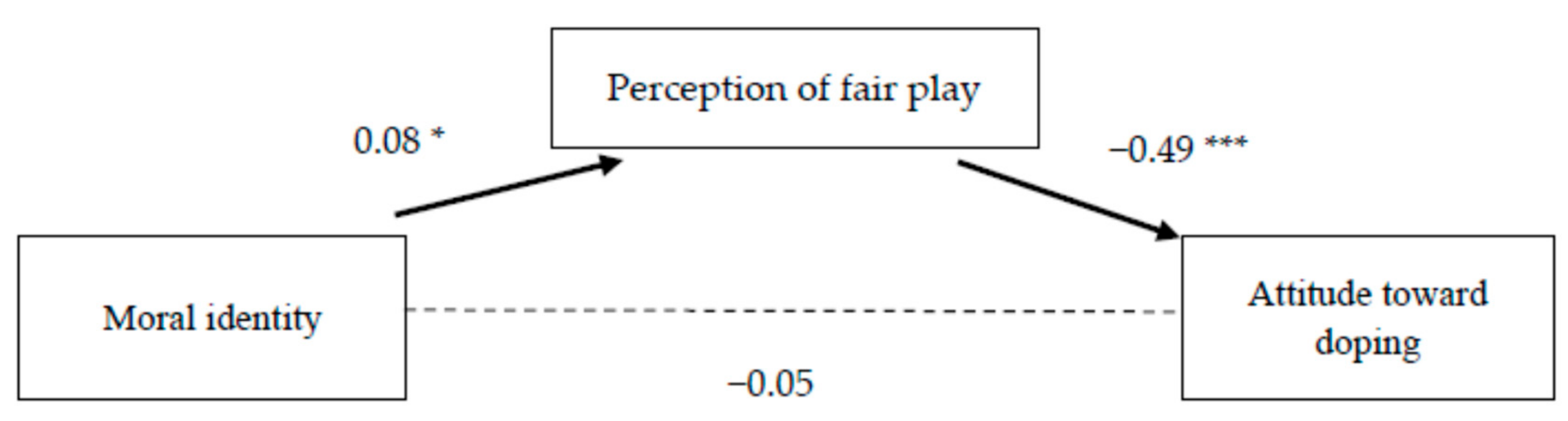

| Direct effects of moral identity on | ||||

| Attitude to doping | −0.05 | [−0.11. 0.06] | ||

| Perception of fair play | 0.08 * | [0.01. 0.16] | ||

| Direct effect of perception of fair play on | ||||

| Attitude to doping | −0.49 *** | [−0.65. −0.33] | ||

| Indirect effect on attitudes to doping via | ||||

| Perception of fair play | −0.08 * | [−0.17. −0.01] | −0.07 * | [−0.15. −0.01] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sukys, S.; Tilindiene, I.; Majauskiene, D.; Karanauskiene, D. Moral Identity and Attitudes towards Doping in Sport: Whether Perception of Fair Play Matters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111531

Sukys S, Tilindiene I, Majauskiene D, Karanauskiene D. Moral Identity and Attitudes towards Doping in Sport: Whether Perception of Fair Play Matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111531

Chicago/Turabian StyleSukys, Saulius, Ilona Tilindiene, Daiva Majauskiene, and Diana Karanauskiene. 2021. "Moral Identity and Attitudes towards Doping in Sport: Whether Perception of Fair Play Matters" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111531

APA StyleSukys, S., Tilindiene, I., Majauskiene, D., & Karanauskiene, D. (2021). Moral Identity and Attitudes towards Doping in Sport: Whether Perception of Fair Play Matters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111531