Abstract

COVID-19 respiratory failure is a life-threatening condition. Oxygenation targets were evaluated in a non-ICU setting. In this retrospective, observational study, we enrolled all patients admitted to the University Hospital of Genoa, Italy, between 1 February and 31 May 2020 with an RT-PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2. PaO2, PaO2/FiO2 and SatO2% were collected and analyzed at time 0 and in case of admission, patients who required or not C-PAP (groups A and B) were categorized. Each measurement was correlated to adverse outcome. A total of 483 patients were enrolled, and 369 were admitted to hospital. Of these, 153 required C-PAP and 266 had an adverse outcome. Patients with PaO2 <60 and >100 had a higher rate of adverse outcome at time 0, in groups A and B (OR 2.52, 3.45, 2.01, respectively). About the PaO2/FiO2 ratio, the OR for < 300 was 3.10 at time 0, 4.01 in group A and 4.79 in group B. Similar odds were found for < 200 in any groups and < 100 except for group B (OR 11.57). SatO2 < 94% showed OR 1.34, 3.52 and 19.12 at time 0, in groups A and B, respectively. PaO2 < 60 and >100, SatO2 < 94% and PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 300 showed at least two- to three-fold correlation to adverse outcome. This may provide simple but clear targets for clinicians facing COVID-19 respiratory failure in a non ICU-setting.

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 outbreak has challenged health-care systems across the world as it is associated with high mortality and morbidity [1]. Upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are the most common and serious causes of hospitalization and demand for critical care environment [2,3,4]. Clinically, acute hypoxemic respiratory failure is the dominant finding whilst hypercapnia is rare [5]. Facial mask oxygen, high flow nasal cannula (HFNC), helmet C-PAP (continuous positive air pressure) and non-invasive ventilation (NIV) are the alternatives to mechanical ventilation in non-intensive care unit (ICU) settings to maintain adequate level of blood oxygenation [6]. Persistent hypoxia, hyperactivation of inflammatory and immune mechanisms and hypercoagulable state are responsible for increased risk of cerebrovascular events and cardiac dysfunction [7,8]. The brain is especially sensible to oxygen content changes causing cerebral blood flow control derangements and increased anaerobic glycolysis products (lactic acid, oxygen free radicals, lipid peroxides) leading to interstitial brain edema, intracranial hypertension and decreased ATP production [9,10].

Adaptation to hypoxia and oxygen toxicity are well known mechanisms in critical ill patients, and these elements represent a challenge in the understanding and management of ARDS in COVID-19 [11,12,13]. Because of socio-cultural, organizational and personal convictions, many patients come to hospital observation after many days of symptoms onset (often more than one week) [14,15,16]. In those developing COVID-19-related respiratory failure, prolonged hypoxia causes adaptative systems activation [17]. Alveolar ventilation, cardiac output and red cell mass increase are early mechanisms to maintain tissue oxygen delivery (DO2) whilst reduction in ATP production and cellular metabolic processes downregulation represent chronic adaptative responses to cellular oxygen consumption (VO2) [18,19].

Supplemental oxygen, irrespective of the interface used, may cause a derangement of these adaptation mechanisms and direct harm to many organs through reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [20]. Moreover, supranormal arterial oxygenation has been related to adverse events like reduced myocardial function and coronary blood flow, increased mortality in stroke and septic shock and neutrophil-induced oxidative stress [21,22,23].

Peripheral oxygen saturation (SatO2) and arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis are commonly used to assess oxygenation in non-ICU settings. PaO2/FiO2 ratio is the index used to classify the severity of ARDS according to the Berlin definition even though most of the evidence derives from intensive care settings [24]. HACOR score and COX index has been proposed to predict adverse outcomes in patients on C-PAP and HFNC, respectively, but they were not considered for this study due to a lack of data and device availability [25,26]. Whilst several consensus statements were in place that recommended maintaining the lower thresholds of SatO2 ≥ 94% and PaO2 > 60 mmHg, few data were available about the “higher” threshold especially for PaO2 level in COVID-19 [27].

The primary objective of this study was to analyze SatO2, PaO2/FiO2 ratio and PaO2 values in patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure and correlate these parameters with adverse outcomes.

Secondarily, we aimed to identify SatO2, PaO2/FiO2 ratio and PaO2 relevant thresholds outcomes related to provide simple but clear targets for clinical management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

This is a retrospective observational study considering all patients found having a reverse transcription of polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) positive for SARS-CoV-2 to a nasopharyngeal swab.

We collected data from 1 February to 31 May 2020 about all the patients admitted to the Emergency Department at the University Hospital of Genoa, Italy. This is a tertiary care hospital with full facilities and a total of 700 beds, and at the time of the study, almost 200 beds were dedicated to COVID-19 patients (of these, 25 were ICU beds, and the others were reorganized from internal medicine, infective disease, rheumatology and endocrinology wards to face the outbreak). Of each patient, informatic charts were reviewed using our unified healthcare information system (TrackCare© 1996–2021 InterSystems Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA) from hospital admission to discharge or death. Furthermore, we looked at hospital readmission within 30 days from discharge.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Institutional Ethics Committee (CER Liguria: 460/2020—DB id 10865).

2.2. Particitants and Data Collection

All patients who were >18 years old with a RT-PCR positive for SARS-CoV-2 admitted to the Emergency Department were eligible for the study.

The exclusion criteria were the following: lack of data about PaO2, SatO2 and PaO2/FiO2 ratio at hospital admission; those with positive swab for SARS-CoV-2 after hospital admission; presentation not related to COVID-19 clinical feature (for example, trauma or surgical patients); direct ICU admission; expectance of survival <6 h.

For admitted patients in this peculiar pandemic situation, ICU admission criteria were: PaO2 < 60 and/or PaO2/FiO2 < 100 despite optimization of C-PAP set-up, uncontrolled respiratory distress, GCS < 9, age below life expectancy (82 years), no end-of-stage chronic disease.

C-PAP indications were: PaO2 < 60 and/or PaO2/FiO2 < 100 despite optimization of oxygen mask set-up; signs of respiratory distress.

Nobody received HFNC as this device was not available at our hospital at the time of the study.

For each patient we collected:

- -

- Age;

- -

- Gender;

- -

- Coexisting disorder (hypertension, smoke, hypercholesterolemia, heart failure, COPD, pulmonary restrictive diseases, coagulopathies, immunodepression, diabetes, vascular-artery disease, chronic kidney disease, active solid cancer, active hematological disorder);

- -

- Medications (ACE inhibitors, steroids, oral anticoagulant);

- -

- Vital parameters at admission (systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, SatO2%, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature);

- -

- Laboratory test at admission (white cell count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, aPTT, INR, d-dimer, fibrinogen, CRP, procalcitonin, lactate deydrogenase, IL-6, creatine-kinase, ferritin, troponin, creatinine, NT-probnp);

- -

- Arterial blood gas analysis: pH, pCO2, PaO2, PaO2/FiO2 ratio;

- -

- Number of patients requiring supplemental oxygen via face mask and those requiring non-invasive ventilation/C-PAP helmet.

2.3. Outcomes Measures

ABG values were reviewed from admission to hospital discharge or until the finding of one of the adverse outcomes. We analyzed these data considering three different phases: first ABGs made at hospital admission in the Emergency Department (Time 0), ABGs made during hospital admission in those not on C-PAP (group A), ABGs made during hospital admission in those on C-PAP helmet (group B). Patients admitted to hospital not requiring C-PAP could have switched to C-PAP helmet or remained on face mask on the basis of clinical judgement. ABGs were made at least daily in those on face mask and more frequently for those on C-PAP helmet.

At time 0, pH, PaO2, PaO2/FiO2 and SatO2 were collected. For group A and group B, we collected the best and worst PaO2, the worst PaO2/FiO2 and SatO2 values found at any time from admission.

ABGs values were categorized as follows and matched with the presence of at least one adverse outcome:

- SatO2 < 94% versus SatO2 ≥ 94% (value chosen on the basis of WHO indication).

- PaO2/FiO2 ratio subdivided using the threshold of 100–200–300 according to the Berlin criteria of ARDS.

- PaO2 < 60 and >100 mmHG (out of normal range) versus PaO2 60–100 (in range).

As adverse outcomes we considered: invasive ventilation, ICU admission, intrahospital mortality, C-PAP-failure, hospital readmission within 30 days from discharge, length of hospital stay. We defined “C-PAP failure” the need to restart C-PAP after a weaning deemed effective.

2.4. Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Patients’ characteristics were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and expressed as absolute values along with percentages for categorical variables.

Of the arterial blood gas parameters, PaO2 levels were compared and categorized in <60 mmHg, 60–100 mmHg, >100 mmHg; SatO2 in < 94 and ≥94%, PaO2/FiO2 < 100, 100–200, 200–300 and ≥300.

The population was subdivided according to the presence of at least one adverse outcome (in-hospital mortality, IOT, C-PAP failure, hospital readmission within 30 days from discharge). PaO2, SatO2 and PaO2/FiO2 categories as identified above were compared between the two sub-populations with and without adverse outcome. For the comparison we used the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to identify arterial blood gas analysis parameter independently associated with adverse outcomes. To establish the OR of PaO2 values, we assigned 0 to a PaO2 range between 60 and 100 mmHg (representing the ideal target of normoxia) and 1 to PaO2 < 60 mmHg and >100 mmHg considered values out of the favorable range. Having recalculated PaO2 continuous values into binomial variable (favorable: PaO2 60–100; non-favorable: PaO2 < 60 and >100), we calculated for each category the odds for adverse outcomes. Similarly, we calculated the OR for adverse outcomes of SatO2 <94% and of PaO2/FiO2 < 100, 100–200, 200–300 according to the international definition for the stratification of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

All tests were two-sided, and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We included all participants for whom the variables of interest were available in the final analysis, without imputing missing data. All statistical analyses were done with Stata/SE 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

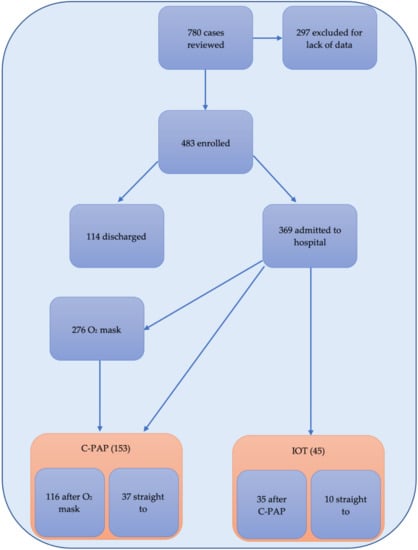

Between 1 March and 31 May 2020, 780 individuals were eligible for the study. Of these, 483 were enrolled for full analysis whilst 269 excluded for lack of data or the presence of exclusion criteria. A total of 369 (76.40%) were admitted to hospital: initially 276 were managed with oxygen mask, 68 with C-PAP helmet, and 10 were intubated. Of the 346 in oxygen mask, 116 needed C-PAP during admission having an overall of 153 treated with C-PAP. Of these, 35 needed IOT and ICU admission having an overall of 45 patients who needed mechanical ventilation. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients and oxygen strategies observed reporting enrolled patients; those discharged vs those admitted to hospital and the number of those admitted requiring oxygen mask, C-PAP and mechanical ventilation (IOT).

3.1. Characteristic of Patients

Median population age was 74 (IQR 61–83), and 278 (57.56%) were male. Coexisting disorders, home medications, vital parameters, laboratory test and arterial blood gas analysis at admission are reported in Table 1. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity (n = 205, 42.44%) followed by vascular artery disease (n = 86, 17.81%), hyper-cholesterolemia (n = 58, 12.01%), diabetes (n = 49, 10.14%) and solid cancer with active treatment (n = 50, 10.35%). Most of the patients were hemodynamically stable with median SatO2 95% (IQR 91–97) and median respiratory rate of 20, (IQR 18–25). Laboratory tests showed lymphopenia (0.9 10⁹ cells/L IQR 0.6–1.2), increased D-dimer and C-reactive protein.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients enrolled for the study.

Overall, 266/483 experienced an adverse outcome: intra-hospital mortality was 38.07% (185/483), n = 45 (9.26%) patients were admitted to ICU for mechanical ventilation, n = 70 (14.40%) met the criteria for C-PAP failure, and n = 40 (8.23%) had a hospital readmission within 30 days from discharge.

3.2. Outcome and Blood Gas Analysis

Blood gas analysis values showed at time 0 in the population with and without adverse outcome, respectively: a median of PaO2 70 mmHg (IQR 61–83) versus 64 mmHg (IQR 54–77) (p < 0.001); a median of PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 314 (IQR 266–371) versus 251 (IQR 165–310) (p < 0.001); a median of SatO2 95% (IQR 93–97) versus 95% (IQR 90–97) (p < 0.001).

For those who required hospital admission, we identified 217 patients as group A (those who were not on C-PAP) and 140 patients as group B (those on C-PAP).

In any group, patients with SatO2 < 94% experienced a significantly higher rate of adverse outcome at time 0, group A and group B on C-PAP (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of patients based on SatO2 values at time 0, in Group A and Group B, divided into those with and without at least one adverse outcome.

About PaO2/FiO2 ratio, categorized into the chosen threshold of <100, 100–200, 200–300, >300, we found significant differences in these groups in terms of adverse outcome mainly between those with 0–300 versus > 300 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of patients based on PaO2/FiO2 values at time 0, in Group A and Group B, divided into those with and without at least one adverse outcome.

Regarding PaO2 values, we found, at time 0 in group A and group B, that not only those with PaO2 < 60 but also those with PaO2 > 100 had a higher rate of adverse outcomes with respect to those with PaO2 60–100 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of patients based on PaO2 values at time 0, in Group A and Group B, divided into those with and without at least one adverse outcome.

Logistic Analysis Results

The ORs derived from logistic regression models for at least one adverse outcome, in-hospital mortality and IOT of SatO2 < 94% versus SatO2 ≥ 94%, PaO2/FiO2 with thresholds of 100–200–300 and PaO2 < 60 and > 100 versus PaO2 60–100 are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

OR values (95% CI) related to the comparison of SatO2 < 94% versus SatO2 ≥ 94%, of PaO2/FiO2 category with a threshold of 100, 200 and 300 and of PaO2 < 60 and > 100 versus PaO2 60–100 for the presence of at least one adverse outcome and in-hospital mortality.

4. Discussion

This study describes SatO2, PaO2/FiO2 ratio and PaO2 in a cohort of patients affected by COVID-19 regardless of oxygenation strategies chosen out of an ICU setting. We found that SatO2 < 94%, PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 300 and PaO2 < 60 and > 100 were strongly associated with adverse outcomes.

SatO2 levels have been correlated to in-hospital mortality in many studies and are considered a relevant index in the management of acute respiratory failure from COVID-19 [6,28,29]. In this study, at time 0 SatO2 < 94% had 1.98 OR not only for in-hospital mortality but for the overall outcomes, more significantly the risk is doubled for those already on facial mask supplemental oxygen (Group A) and tenfold for those on C-PAP (Group B). Even if this is consistent with the pathophysiology of the disease [30], evidences are controversial: in a multicenter cohort study, Aliberti et al. found no significant difference in SatO2 levels between those who succeeded and failed helmet C-PAP [31] whilst other studies found worst outcomes for lower SatO2 levels [19,32].

PaO2/FiO2 ratio results are very much in line with those from previous studies about acute respiratory failure COVID-19 or non-COVID-19 related [33,34]. For those with values < 300, we found a three- to fourfold correlation with adverse outcomes at time 0, on facial oxygen mask and on C-PAP. Interestingly, the odds ratio did not vary much between the categories <100, <200, <300 except for <100 on C-PAP that showed much higher odds. This could be explained by the gravity of respiratory failure in patients without a chance of mechanical ventilation. In the work of Villar et al. [35], since then confirmed in many other studies mainly from ICU settings, PaO2/FiO2 is considered a predictor of adverse outcomes [36,37]. However, experimental studies reported a nonlinear relationship between PaO2 and FiO2 due to the degree of ventilation-perfusion ratio and pulmonary shunts [38,39]. Furthermore, even considering a fixed degree of shunts, PaO2/FiO2 fluctuates unpredictably for PaO2 values > 100 mmHg and varies with the mathematical-experimental model considered [40,41]. Thus, it seems plausible that in our study PaO2/FiO2 values < 300 identified patients at higher risk of adverse outcome, but it was not clinically relevant for values between 0 and 300.

About PaO2 values, we found a significant correlation with adverse outcome both for PaO2 < 60 mmHg and >100 mmHg at time 0, for those on facial mask oxygen and those on helmet C-PAP (see Table 4), having grouped this cohort together with “out of range” PaO2 values (<60 mmHg plus >100 mmHg versus 60–100 mmHg) for logistic regression analysis. Looking at the worst PaO2 detected, OR analysis showed a two- to threefold higher risk for overall adverse outcome and IOT, but about the best PaO2, results did not reach a statistical significance (see Table 5).

As reported in Table 1, we did not find significant differences of hemodynamic parameters and ABG values between time 0, groups A and B. Furthermore, mortality and hospital readmission rate were similar in groups A and B. This is consistent with the pathophysiology of COVID-19 disease that rarely causes severe respiratory failure and shock [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Moreover, it suggests that a proper oxygen and ventilation management prevent adverse outcomes [43].

Among physicians, whilst hypoxia is a well-established index of poor outcomes in ARDS, both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 related [44,45], hyperoxia is less considered as being potentially harmful in clinical practice in acutely ill adults other than those with COPD or chronic pulmonary diseases [22,46,47]. Even in an ICU setting, de Graff et al. found poor clinical response in term of FiO2 adjustment in ventilated hyperoxic patients [48]. High arterial oxygen level, especially after a period of sustained hypoxia as happens in case of late hospital presentation, can have detrimental effects on multiple organs functioning due to a reperfusion injury and adaptation system derangement [49,50].

Summing up, we observed that altered SatO2 and PaO2 values are accurate predictors of adverse outcome irrespective of the oxygen strategies used. This mirrors physiological oxygen tissues delivery as both SatO2 and PaO2 represent arterial oxygen content [51,52]. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether Hb and cardiac output may have a significant role in ARDS COVID-19 related.

5. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, we were not able to obtain all the data needed, so many patients had to be excluded from the analysis. Second, we analyzed arterial blood gas variables present on the patients’ electronic chart reporting the lowest values for PaO2/FiO2 and SatO2% and the lowest and highest values for PaO2. This is a simplification of the real pathophysiology whilst a continuous monitoring and analysis could have led to a more precise and consistent result. However, it is hard but necessary to find a way to summarize parameters variations, and it is difficult to obtain data in a non-ICU setting where continuous monitoring is not possible. A future prospective standardized study may address this with less bias.

Finally, we have to consider that at the time of the first wave, no specific recommendations were in place in our hospital to manage COVID-19 respiratory failure in terms of oxygen, PEEP and FiO2 administration, and furthermore, many non-intensivist physicians were involved so that clinical variability and experience could have led to a different outcome.

6. Conclusions

In this retrospective analysis, we found that SatO2 < 94%, PaO2/FiO2 < 300 and PaO2 < 60 and PaO2 > 100 correlate with a worst outcome. Hyperoxia should be avoided as it was found to be detrimental. Improving the PaO2/FiO2 ratio if already below 300 did not seem to predict a better outcome. Thus, it seems wiser to keep SatO2 and PaO2 in normal range values rather than improve the PaO2/FiO2 ratio. Even if these results are pretty much in line with general indications and clinical practice, these thresholds could give few but precise indications for physicians facing respiratory failure in COVID-19 patient in a non-ICU setting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and L.M.; methodology, S.S. and L.M.; formal analysis, M.S. (Marina Sartini) and M.L.C.; data curation, P.B., O.C., P.C., L.C. (Luca Castellani), L.C. (Ludovica Ceschi) and M.S. (Marzia Spadaro); writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, S.S., L.M., C.B. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We obtained the consensus from our regional Ethical Committee (CER Liguria: 460/2020—DB id 10865).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. However, each patient seen in our hospital has to sign a consent form for data collection and management, and all subjects signed that form.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in our database (repository: Stefano Sartini, UOC MECAU, Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the trainees in Emergency Medicine of the University of Genoa who supported us in accomplishing this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ARDS | acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| HFNC | high flow nasal cannula |

| C-PAP | continuous positive air pressure |

| NIV | non-invasive ventilation |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| DO2 | tissue oxygen delivery |

| VO2 | cellular oxygen consumption |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SatO2 | Peripheral oxygen saturation |

| ABG | arterial blood gas |

| PaO2 | partial pressure of arterial oxygen |

| PaO2/FiO2 | partial pressure of arterial oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen rate |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcription of polymerase chain reaction |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| ACE | angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| aPTT | activated partial thromboplastin time |

| INR | International Normalized Ratio |

| NT-proBNP | N-Terminal Fragment of the Prohormone Brain-Type Natriuretic Peptide |

| IOT | mechanical ventilation |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CIs | confidence intervals |

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moghadas, S.M.; Shoukat, A.; Fitzpatrick, M.; Wells, C.R.; Sah, P.; Pandey, A.; Sachs, J.D.; Wang, Z.; Meyers, L.A.; Singer, B.H.; et al. Projecting hospital utilization during the COVID-19 outbreaks in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9122–9126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Fang, X.; Cai, Z.; Wu, X.; Gao, X.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Comorbid Chronic Diseases and Acute Organ Injuries Are Strongly Correlated with Disease Severity and Mortality among COVID-19 Patients: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Research 2020, 2020, 2402961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grasselli, G.; Pesenti, A.; Cecconi, M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early experience and forecast during an emergency response. Jama 2020, 323, 1545–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Management COVID-19: Interim Guidance, 27 May 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332196 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Qureshi, A.I.; Baskett, W.I.; Huang, W.; Shyu, D.; Myers, D.; Raju, M.; Shyu, C.R. Acute ischemic stroke and COVID-19: An analysis of 27 676 patients. Stroke 2021, 52, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, B.; Brady, W.J.; Koyfman, A.; Gottlieb, M. Cardiovascular complications in COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1504–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellawan, J.M.; Harrell, J.W.; Roldan-Alzate, A.; Wieben, O.; Schrage, W.G. Regional hypoxic cerebral vasodilation facilitated by diameter changes primarily in anterior versus posterior circulation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Casas, A.I.; Geuss, E.; Kleikers, P.W.M.; Mencl, S.; Herrmann, A.M.; Buendia, I.; Egea, J.; Meuth, S.G.; Lopez, M.G.; Kleinschnitz, C.; et al. NOX4-dependent neuronal autotoxicity and BBB breakdown explain the superior sensitivity of the brain to ischemic damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 12315–12320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Girardis, M.; Busani, S.; Damiani, E.; Donati, A.; Rinaldi, L.; Marudi, A.; Morelli, A.; Antonelli, M.; Singer, M. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit: The oxygen-ICU randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016, 316, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, L.; Locatelli, F. Hypoxia response and acute lung and kidney injury: Possible implications for therapy of COVID-19. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 13, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Ma, X. Acute respiratory failure in COVID-19: Is it “typical” ARDS? Crit. Care 2020, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, G.M.; Mitchell, R.D.; Wu, J.; Rajiv, P.; Bannon-Murphy, H.; Amos, T.; Brichko, L.; Brennecke, H.; Noonan, M.P.; Mitra, B.; et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of emergency department patients with suspected COVID-19: Initial results from the COVID-19 Emergency Department Quality Improvement Project (COVED-1). Emerg. Med. Australas. 2020, 32, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzerini, M.; Barbi, E.; Apicella, A.; Marchetti, F.; Cardinale, F.; Trobia, G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapey, E.; Gallier, S.; Mainey, C.; Nightingale, P.; McNulty, D.; Crothers, H.; Evison, F.; Reeves, K.; Pagano, D.; Denniston, A.K. Ethnicity and risk of death in patients hospitalised for COVID-19 infection in the UK: An observational cohort study in an urban catchment area. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaja, M.; Milano, G. Adaptation to Hypoxia: A Chimera? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKenna, H.T.; Murray, A.J.; Martin, D.S. Human adaptation to hypoxia in critical illness. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 129, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connett, R.J.; Honig, C.R.; Gayeski, T.E.; Brooks, G.A. Defining hypoxia: A systems view of VO2, glycolysis, energetics, and intracellular PO2. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990, 68, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.M. Pulmonary oxygen toxicity. Chest 1985, 88, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, H.S. Paradigms of oxygen therapy in critically Ill patients. J. Intensive Crit. Care 2017, 3, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zaytoun, T.M.; Elsayed, H.E.; Elsayed, S.E. The relation between arterial hyperoxia and mortality among intensive care unit patients with septic shock. Res. Opin. Anesth. Intensive Care 2020, 7, 41. [Google Scholar]

- LaForge, M.; Elbim, C.; Frère, C.; Hémadi, M.; Massaad, C.; Nuss, P.; Benoliel, J.-J.; Becker, C. Tissue damage from neutrophil-induced oxidative stress in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Force, A.D.T.; Ranieri, V.M.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Thompson, B.T.; Ferguson, N.; Caldwell, E.; Fan, E.; Camporota, L.; Slutsky, A.S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA 2012, 307, 2526–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Han, X.; Bai, L.; Zhou, L.; Huang, S. Assessment of heart rate, acidosis, consciousness, oxygenation, and respiratory rate to predict noninvasive ventilation failure in hypoxemic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, L.A.; Abdelgawad, T.T.; Farrag, N.S.; Abdelwahab, H.W. Validity of ROX index in prediction of risk of intubation in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Adv. Respir. Med. 2021, 89, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Clinical Care for Severe Acute Respiratory Infection: Toolkit. WHO/2019-nCoV/SARI_toolkit/2020.1. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/clinical-care-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infections-tool-kit (accessed on 11 April 2020).

- Becerra-Muñoz, V.M.; Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Eid, C.M.; García Aguado, M.; Romero, R.; Huang, J.; Mulet, A.; Ugo, F.; Rametta, F.; Liebetrau, C.; et al. Clinical profile and predictors of in-hospital mortality among older patients hospitalised for COVID-19. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikami, T.; Miyashita, H.; Yamada, T.; Harrington, M.; Steinberg, D.; Dunn, A.; Siau, E. Risk Factors for Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in New York City. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 36, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasselli, G.; Tonetti, T.; Protti, A.; Langer, T.; Girardis, M.; Bellani, G.; Laffey, J.; Carrafiello, G.; Carsana, L.; Rizzuto, C.; et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: A multicentre prospective observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, S.; Radovanovic, D.; Billi, F.; Sotgiu, G.; Costanzo, M.; Pilocane, T.; Saderi, L.; Gramegna, A.; Rovellini, A.; Perotto, L.; et al. Helmet CPAP treatment in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: A multicentre cohort study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2001935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vita, N.; Scotti, L.; Cammarota, G.; Racca, F.; Pissaia, C.; Maestrone, C.; Colombo, D.; Olivieri, C.; Della Corte, F.; Barone-Adesi, F.; et al. Predictors of intubation in COVID-19 patients treated with out-of-ICU continuous positive airway pressure. Pulmonology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, C.; Suarez-Sipmann, F.; Mellado-Artigas, R.; Hernández, M.; Gea, A.; Arruti, E.; Aldecoa, C.; Martínez-Pallí, G.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Slutsky, A.S.; et al. Clinical features, ventilatory management, and outcome of ARDS caused by COVID-19 are similar to other causes of ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 2200–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellani, G.; Laffey, J.G.; Pham, T.; Madotto, F.; Fan, E.; Brochard, L.; Esteban, A.; Gattinoni, L.; Bumbasirevic, V.; Piquilloud, L.; et al. Noninvasive Ventilation of Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Insights from the LUNG SAFE Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villar, J.; Blanco, J.; Del Campo, R.; Andaluz-Ojeda, D.; Díaz-Domínguez, F.J.; Muriel, A.; Córcoles, V.; Suarez-Sipmann, F.; Tarancón, C.; González-Higueras, E.; et al. Assessment of PaO2/FiO2 for stratification of patients with moderate and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiner, J.R.; Weiskopf, R.B. Evaluating pulmonary function: An assessment of PaO2/FIO2. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, e40–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santus, P.; Radovanovic, D.; Saderi, L.; Marino, P.; Cogliati, C.; De Filippis, G.; Rizzi, M.; Franceschi, E.; Pini, S.; Giuliani, F.; et al. Severity of respiratory failure at admission and in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19: A prospective observational multicentre study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e043651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.B. State of the art: Ventilation-perfusion relationships. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1977, 116, 919–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzker, D.R. Gas Exchange in the Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Clin. Chest Med. 1982, 3, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, M.S.; Klocke, R.A. Variability of indices of hypoxemia in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 25, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbing, D.S.; Kjærgaard, S.; Smith, B.W.; Espersen, K.; Allerød, C.; Andreassen, S.; Rees, S.E. Variation in the PaO 2/FiO 2 ratio with FiO 2: Mathematical and experimental description, and clinical relevance. Crit. Care 2007, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Rhodes, A.; Cheng, A.C.; Peacock, S.J.; Prescott, H.C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. JAMA 2020, 324, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoğlu, U.; Chatburn, R.; Duggal, A. Optimal Respiratory Assistance Strategy for Patients with COVID-19. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 916–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, D.; Hraiech, S.; Boutin, E.; Lacherade, J.C.; Boissier, F.; Pham, T.; Richard, J.C.; Thille, A.W.; Ehrmann, S.; Lascarrou, J.B.; et al. Hypoxemia in the ICU: Prevalence, treatment, and outcome. Ann. Intensive Care 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kashani, K.B. Hypoxia in COVID-19: Sign of Severity or Cause for Poor Outcomes. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, F.; Kang, J.; Maltenfort, M.; Vibbert, M.; Urtecho, J.; Athar, M.K.; Jallo, J.; Pineda, C.; Tzeng, D.; McBride, W.; et al. Association between hyperoxia and mortality after stroke: A multicenter cohort study. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Kim, L.H.-Y.; Young, P.; Zamiri, N.; Almenawer, S.A.; Jaeschke, R.; Szczeklik, W.; Schünemann, H.J.; Neary, J.D.; Alhazzani, W. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1693–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, A.E.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Binnekade, J.M.; de Jonge, E. Clinicians’ response to hyperoxia in ventilated patients in a Dutch ICU depends on the level of FiO 2. Intensive Care Med. 2011, 37, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, D.S.; Grocott, M.P.W. Oxygen therapy in critical illness: Precise control of arterial oxygenation and permissive hypoxemia. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.; Chandel, N.S.; Simon, M.C. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia through hypoxia inducible factors and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliynyk, O.V.; Rorat, M.; Barg, W. Oxygen metabolism markers as predictors of mortality in severe COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 103, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.M. Pathophysiology of Oxygen Delivery in Respiratory Failure. Chest 2005, 128, 547S–553S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).