Development and Testing of a Community-Based Intervention to Address Intimate Partner Violence among Rohingya and Syrian Refugees: A Social Norms-Based Mental Health-Integrated Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Global Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence

1.2. Increased Risk of Intimate Partner Violence during Conflict and Displacement

1.3. Barriers to Help-Seeking

1.4. Intimate Partner Violence, Social Norms and Gender Roles

1.5. Mental Health and Intimate Partner Violence

1.6. Interventions for Intimate Partner Violence: Group-Based Models

1.7. Interventions for Intimate Partner Violence: Messaging Campaigns

1.8. Participatory Interventions Addressing Social Norms and Mental Health

1.9. Current Study

2. Study 1. Workshop Implementation and Assessment

2.1. Study 1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Workshop Curricula Development and Faciltiator Training

2.1.2. Workshop Participants: Sampling, and Recruitment

2.1.3. Workshop Implementation

2.1.4. Interviews

2.1.5. Analysis Approach

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Demographics and Prevalence of IPV

2.2.2. Outcomes

2.2.3. Participant Satisfaction, Perceived Impact, and Reactions to Research Participation

3. Study 2. Poster Campaign Development and Testing

3.1. Study 2. Materials and Methods

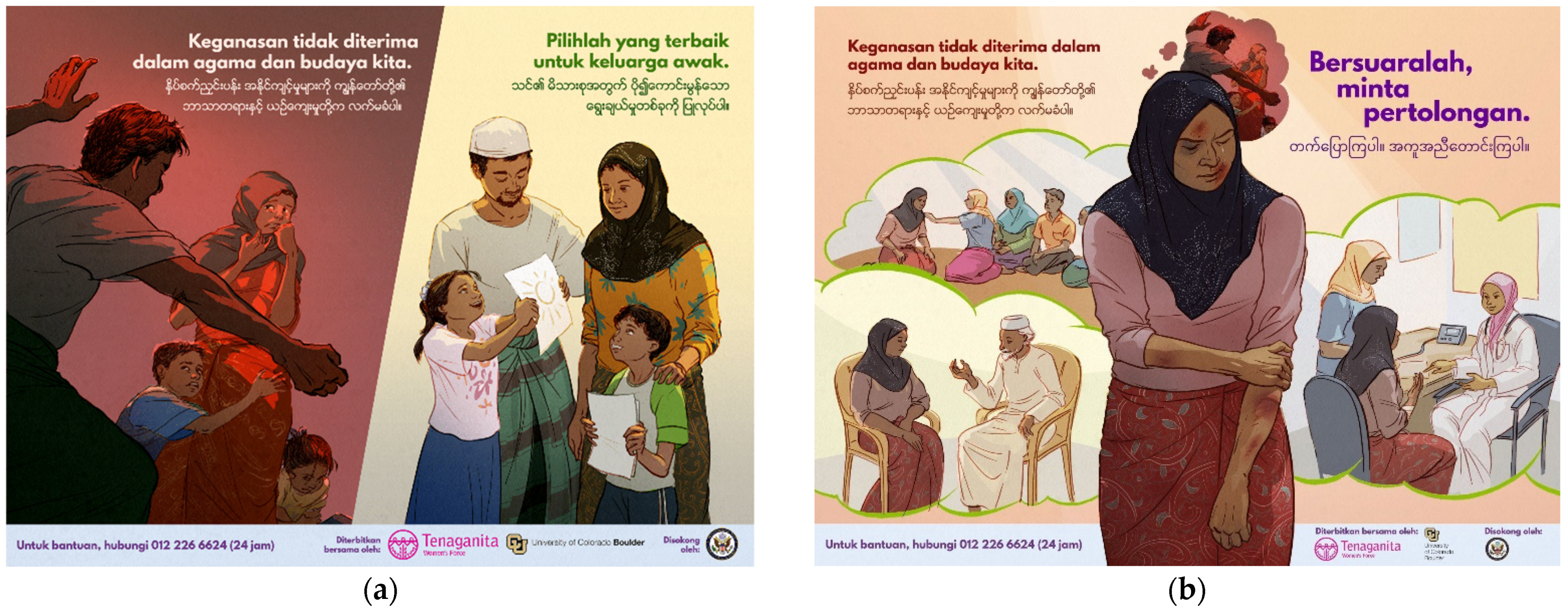

3.1.1. Poster Development

3.1.2. Poster Testing: Research Design

3.1.3. Participants: Sampling and Recruitment

3.1.4. Interviews

3.1.5. Analysis Approach

3.2. Results: Study 2

3.2.1. Demographics, Prevalence of IPV and Help-Seeking

3.2.2. Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Studies 1 and 2

4.2. IPV Prevalence and Willingness to Report

4.3. Acceptability of IPV, Gender Roles/Norms

4.4. Help-Seeking and Help-Giving

4.5. Problem-Solving Efficacy and Social Cohesion

4.6. Mental Health, Functioning, and Coping

5. Limitations, Future Research, and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates. Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Intimate Partner Violence; Center for Disease Control: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- García-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, L.C.; Morris, R.; Hegarty, K.; García-Moreno, C.; Feder, G. Categories and health impacts of intimate partner violence in the World Health Organization multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delkhosh, M.; Ardalan, A.; Rahimiforoushani, A.; Keshtkar, A.; Farahani, L.A.; Khoei, E.M. Interventions for prevention of intimate partner violence against women in humanitarian settings: A protocol for a systematic review. PLoS Curr. 2017, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tol, W.A.; Greene, M.C.; Likindikoki, S.; Misinzo, L.; Ventevogel, P.; Bonz, A.G.; Mbwambo, J.K. An integrated intervention to reduce intimate partner violence and psychological distress with refugees in low-resource settings: Study protocol for the Nguvu cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barada, R.; Potts, A.; Bourassa, A.; Contreras-Urbina, M.; Nasr, K. I go up to the edge of the valley, and I talk to god: Using mixed methods to understand the relationship between gender-based violence and mental health among Lebanese and Syrian refugee women engaged in psychosocial programming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, S.; James, L.E.; Welton-Mitchell, C. Intimate partner abuse among Syrians in Lebanon: Implications for interventions. (in press)

- Welton-Mitchell, C.; Bujang, N.A.; Hussin, H.; Husein, S.; Santoadi, F.; James, L.E. Intimate partner abuse among Rohingya in Malaysia: Assessing stressors, mental health, social norms and help-seeking to inform interventions. Intervention 2019, 17, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.F.; Gupta, J.; Shuman, S.; Cole, H.; Kpebo, D.; Falb, K.L. What factors contribute to intimate partner violence against women in urban, conflict-affected settings? Qualitative findings from abidjan, côte d’ivoire. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2016, 93, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wirtz, A.L.; Pham, K.; Glass, N.; Loochkartt, S.; Kidane, T.; Cuspoca, D.; Rubenstein, L.S.; Singh, S.; Vu, A. Gender-based violence in conflict and displacement: Qualitative findings from displaced women in Colombia. Confl. Health 2014, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, H.; Kwon, I.; Shamrova, D.; Seon, J. Factors for formal help-seeking among female survivors of intimate partner violence. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Mont, J.; Forte, T.; Cohen, M.M.; Hyman, I.; Romans, S. Changing help-seeking rates for intimate partner violence in Canada. Women Health 2005, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gover, A.R.; Welton-Mitchell, C.; Belknap, J.; Deprince, A.P. When abuse happens again: Women’s reasons for not reporting new incidents of intimate partner abuse to law enforcement. Women Crim. Justice 2013, 23, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyen, L.; Rogic, A.C.; Supol, M. Intimate partner violence and help-seeking behaviour: A systematic review of cross-cultural differences. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2019, 21, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyu, N.; Kanai, A. Prevalence, antecedent causes and consequences of domestic violence in Myanmar. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 8, 244–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, A.; Hayes, B.E. Help-seeking behaviors of intimate partner violence victims: A cross-national analysis in developing nations. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP4705–NP4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.; Silverman, J.G. Domestic violence help-seeking behaviors of South Asian battered women residing in the United States. Int. Rev. Vict. 2007, 14, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, A.S.; Lohman, B.J.; Maldonado, M.M. He said they’d deport me: Factors influencing domestic violence helpseeking practices among Latina immigrants. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripoll, S. Social and cultural factors shaping health and nutrition, wellbeing and protection of the Rohingya within a humanitarian context. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Action Platf. 2017, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Critelli, F.; Yalim, A.C. Improving access to domestic violence services for women of immigrant and refugee status: A trauma-informed perspective. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work. 2020, 29, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Silverman, J. Violence against immigrant women: The roles of culture, context, and legal immigrant status on intimate partner violence. Violence Women 2002, 8, 367–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, A.S.; Lohman, B.J. Barriers preventing Latina immigrants from seeking advocacy services for domestic violence victims: A qualitative analysis. J. Fam. Violence 2015, 30, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, T.; Watts, C.H.; Garcia-Moreno, C.; Devries, K.; Kiss, L.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multicountry study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Knoble, N.B.; Shortt, J.W.; Kim, H.K. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partn. Abus. 2012, 3, 231–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, A.; Glass, N.; Remy, M.M.; Perrin, N. A latent class analysis of gender attitudes and their associations with intimate partner violence and mental health in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, L.; Kotsadam, A. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: An analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mulawa, M.I.; Reyes, H.L.M.; Foshee, V.A.; Halpern, C.T.; Martin, S.L.; Kajula, J.J.; Maman, S. Associations between peer network gender norms and the perpetration of intimate partner violence among urban Tanzanian men: A multilevel analysis. Prev. Sci. 2018, 19, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulla, M.M.; Witte, T.H.; Richardson, K.; Hart, W.; Kassing, F.L.; Coffey, C.A.; Hackman, C.L.; Sherwood, I.M. The causal influence of perceived social norms on intimate partner violence perpetration: Converging cross-sectional, longitudinal, and experimental support for a social disinhibition model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 45, 652–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E.L.; Ball, L. Social Norms Marketing Aimed at Gender Based Violence: A Literature Review; International Rescue Committee: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Husnu, S.; Mertan, B.E. The roles of traditional gender myths and beliefs about beating on self-reported partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 3735–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greifinger, R.; Richards, L.M.; Oo, S.; Khaing, E.E.; Thet, M.M. The role of the private health sector in responding to gender-based violence in Myanmar. PSI 2015. Available online: https://www.psi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Richards-Myanmar-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Spencer, C.M.; Morgan, P.; Bridges, J.; Washburn-Busk, M.; Stith, S.M. The relationship between approval of violence and intimate partner violence in college students. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP212–NP231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James-Hawkins, L.; Cheong, Y.F.; Naved, R.T.; Yount, K.M. Gender norms, violence in childhood, and men’s coercive control in marriage: A multilevel analysis of young men in Bangladesh. Psychol. Violence 2018, 8, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sikweyiya, Y.; Addo-Lartey, A.A.; Alangea, D.O.; Dako-Gyeke, P.; Chirwa, E.D.; Coker-Appiah, D.; Adamu, R.M.K.; Jewkes, R. Patriarchy and gender-inequitable attitudes as drivers of intimate partner violence against women in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yount, K.M.; James-Hawkins, L.; Cheong, Y.F.; Naved, R.T. Men’s perpetration of partner violence in Bangladesh: Community gender norms and violence in childhood. Psychol. Men Masc. 2018, 19, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Masri, R.; Harvey, C.; Garwood, R. Shifting Sands: Changing Gender Roles among Refugees in Lebanon; Oxfam International: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Garzón Segura, A.M.; Carcedo González, R.J. Effectiveness of a prevention program for gender-based intimate partner violence at a Colombian primary school. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haylock, L.; Cornelius, R.; Malunga, A.; Mbandazayo, K. Shifting negative social norms rooted in unequal gender and power relationships to prevent violence against women and girls. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R.; Mclean Hilker, L.; Khan, S.; Fulu, E.; Busiello, F.; Fraser, E. What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls; Evidence Reviews Paper 3: Response mechanisms to prevent violence against women and girls; UK Aid, DFID: London, UK, 2015.

- Meinhart, M.; Seff, I.; Troy, K.; McNelly, S.; Vahedi, L.; Poulton, C.; Stark, L. Identifying the impact of intimate partner violence in humanitarian settings: Using an ecological framework to review 15 years of evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grose, R.G.; Roof, K.A.; Semenza, D.C.; Leroux, X.; Yount, K.M. Mental health, empowerment, and violence against young women in lower-income countries: A review of reviews. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 46, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, C.E.; Resick, P.A. Help-seeking behavior in survivors of intimate partner violence: Toward an integrated behavioral model of individual factors. Violence Vict. 2017, 32, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breet, E.; Seedat, S.; Kagee, A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in men and women who perpetrate intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 34, 2181–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James-Hawkins, L.; Naved, R.T.; Cheong, Y.F.; Yount, K.M. Multilevel influences on depressive symptoms among men in Bangladesh. Psychol. Men Masc. 2019, 20, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, R.C.; Febres, J.; Brasfield, H.; Stuart, G.L. The Prevalence of Mental Health Problems in Men Arrested for Domestic Violence. J. Fam. Violence 2012, 27, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, R.; Nevado-Holgado, A.J.; Molero, Y.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Larsson, H.; Howard, L.M.; Fazel, S. Mental disorders and intimate partner violence perpetrated by men towards women: A Swedish population-based longitudinal study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, L.E.; Welton-Mitchell, C.; Noel, J.R.; James, A.S. Integrating mental health and disaster preparedness in intervention: A randomized controlled trial with earthquake and flood-affected communities in Haiti. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welton-Mitchell, C.; James, L.E.; Khanal, S.N.; James, A.S. An integrated approach to mental health and disaster preparedness: A cluster comparison with earthquake affected communities in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogbe, E.; Harmon, S.; Van den Bergh, R.; Degomme, O. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/mental health outcomes of survivors. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, C.N.; Morse, S.M.; Irvin, N.A.; Green-Manning, A.; Nitsch, L.M.; Burke, J.M.; Campbell, J.C.; Decker, M.R. Concept mapping: Engaging urban men to understand community influences on partner violence perpetration. J. Urban Health 2019, 96, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsberg, M.; Arango, D.J.; Morton, M.; Gennari, F.; Kiplesund, S.; Contreras, M.; Watts, C. Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say? Lancet 2015, 385, 1555–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabold, N.; McMahon, J.; Alsobrooks, S.; Whitney, S.; Mittal, M. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions: State of the field and implications for practitioners. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 21, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno Martín, F.; Alvarez, M.J.; Alonso, E.A.; Villanueva, I.F. Campaigns against intimate partner violence toward women in Portugal: Types of prevention and target audiences. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2020, 29, 876–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, K.; Rubenstein, B.; Stark, L. Preventing Household Violence: Promising Strategies for Humanitarian Settings. The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, CPC Learning Network, UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund, USAID, US Agency for International Development, 2017, 1–96. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Khudejha-Asghar/publication/314243291_Preventing_Household_Violence_Promising_Strategies_for_Humanitarian_Settings/links/5b59a1fbaca272a2d66c21bd/Preventing-Household-Violence-Promising-Strategies-for-Humanitarian-Settings.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Welton-Mitchell, C. Responses to Domestic Violence Public Service Ads: Memory, Attitudes, Affect, and Individual Differences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2012; pp. 1–113. Available online: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/951?utm_source=digitalcommons.du.edu%2Fetd%2F951&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Zhao, X. Health communication campaigns: A brief introduction and call for dialogue. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, B.H.; Kia-Keating, M.; Yusuf, S.A.; Lincoln, A.; Nur, A. Ethical research in refugee communities and the use of community participatory methods. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 44, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.B.; Issa, O.M.; Hahn, E.; Agalab, N.Y.; Abdi, S.M. Developing advisory boards within community-based participatory approaches to improve mental health among refugee communities. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2021, 15, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afifi, R.A.; Abdulrahim, S.; Betancourt, T.; Btedinni, D.; Berent, J.; Dellos, L.; Farrar, J.; Nakkash, R.; Osman, R.; Saravanan, M.; et al. Implementing community-based participatory research with communities affected by humanitarian crises: The potential to recalibrate equity and power in vulnerable contexts. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 66, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L. Researching Violence against Women: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Activists; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.W.; Yuan, N.P.; Cook, S.L.; Abbey, A. Ethnic minority women’s experiences with intimate partner violence: Using community-based participatory research to ask the right questions. Sex Roles 2013, 69, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poleshuck, E.; Mazzotta, C.; Resch, K.; Rogachefsky, A.; Bellenger, K.; Raimondi, C.; Stone, J.T.; Cerulli, C. Development of an innovative treatment paradigm for intimate partner violence victims with depression and pain using community-based participatory research. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 2704–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, B.; Kallestrup, P. Benefits and challenges of using a participatory approach with community-based mental health and psychosocial support interventions in displaced populations. Transcult. Psychiatry 2021, 58, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, N.; Ellis, J.; Farrelly, N.; Hollinghurst, S.; Bailey, S.; Downe, S. What matters to someone who matters to me: Using media campaigns with young people to prevent interpersonal violence and abuse. Health Expect. 2017, 20, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonell, C.; Michie, S.; Reicher, S.; West, R.; Bear, L.; Yardley, L.; Curtis, V.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J. Harnessing behavioural science in public health campaigns to maintain ‘social distancing’in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Key principles. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 617–619. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, A.; Akther, Y.; Noor, M.; Ali, R.; Welton-Mitchell, C. Systematic human rights violations, traumatic events, daily stressors and mental health of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Confl. Health 2020, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.; Akther, Y.; Noor, M.; Welton-Mitchell, C. Mental Health and Conditions in Refugee Camps Matter When Rohingya Living in Bangladesh Consider Returning to Myanmar. Humanit. Pract. Netw. 2021. Available online: https://odihpn.org/blog/mental-health-and-conditions-in-refugee-camps-matter-when-rohingya-living-in-bangladesh-consider-returning-to-myanmar/ (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Smajlovic, A.; Murphy, A.L. Invisible no more: Social work, human rights, and the Syrian refugee crisis. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2020, 5, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Worthington, R.P. Barriers to healthcare access and utilization among urban Syrian refugees in Turkey. J. Stud. Res. 2021, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Rescue Committee & ABAAD. Syrian Women & Girls: FLEEING Death, Facing Ongoing Threats and Humiliation; A gender based violence rapid assessment; International Rescue Committee: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Keedi, A.; Yaghi, Z.; Barker, G. We Can Never Go Back to How Things Were before: A Qualitative Study on War, Masculinities, and Gender Relations with Lebanese and Syrian Refugee Men and Women; ABAAD: Beirut, Lebanon; Promundo: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- James, L.; Michael, S.; Welton-Mitchell, C.; ABAAD. Healthy Relationships, Healthy Community Curriculum: Incorporating Mental Health, Social Norms and Advocacy Approaches to Reduce Intimate Partner Abuse; ABAAD: Beirut, Lebanon, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Welton-Mitchell, C.; James, L.; Tenaganita. Healthy Relationships Manual: Incorporating Mental Health, Social Norms and Human Rights Approaches to Empower Communities.Workshop Manual to Raise Awareness about Intimate Partner Abuse. 3-Day English Language Version 2017/2018–for Rohingya Communities in Malaysia; Tenaganita: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.; Douglas, E.M. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004, 19, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewkes, R.; Levin, J.; Penn-Kekana, L. Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: Findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, K.L.; Jewkes, R.K.; Brown, H.C.; Gray, G.E.; McIntryre, J.A.; Harlow, S.D. Gender based violence, relationship power and risk of prevalent HIV infection among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. Lancet 2004, 363, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollifield, M.; Verbillis-Kolp, S.; Farmer, B.; Toolson, E.C.; Woldehaimanot, T.; Yamazaki, J.; Holland, A.; St. Clair, J.; SooHoo, J. The refugee health screener-15 (RHS-15): Development and validation of an instrument for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in refugees. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, E.; Willard, T.; Sinclair, R.; Kaloupek, D. The costs and benefits of research from the participants’ view: The path to empirically informed research practice. Account. Res. 2001, 8, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, T.A. Effects of self-brand congruity and ad duration on online in-stream video advertising. J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, Y.A. Does subliminal advertisement affect consumer behavior? An exploratory comparative analysis between marketing and non-marketing professionals. In Proceedings of the Fourth Scientific Conference on Economics and Managerial Studies Published in MPRA, Ghoshal, Sumantra, 14 April 2018; Volume 3, pp. 1828–1843. [Google Scholar]

- WHO-UNHCR. Assessing Mental Health and Psychosocial Needs and Resources. Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings. Assessment Schedule of Serious Symptoms in Humanitarian Settings (WASSS) (Field Test Version); WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Myrttinen, H.; Khattab, L.; Naujoks, J. Re-thinking hegemonic masculinities in conflict-affected contexts. Crit. Mil. Stud. 2017, 3, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santirso, F.A.; Gilchrist, G.; Lila, M.; Gracia, E. Motivational strategies in interventions for intimate partner violence offenders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosoc. Interv. 2020, 29, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, A.; Shanahan, F.; Hizazi, A.; Osman, Z. Engaging men to promote resilient communities among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Intervention 2019, 18, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fontelo, A.; Cabaña, A.; Joe, H.; Puig, P.; Moriña, D. Untangling serially dependent underreported count data for gender-based violence. Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 4404–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S.N.; Honea, J.C. Navigating the gender minefield: An IPV prevention campaign sheds light on the gender gap. Glob. Public Health 2016, 11, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhoury, T. Governance strategies and refugee response: Lebanon in the face of Syrian displacement. Int. J. Middle East Stud. 2017, 49, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harandi, T.F.; Taghinasab, M.M.; Nayeri, T.D. The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sikweyiya, Y.; Jewkes, R. Perceptions and experiences of research participants on gender-based violence community based survey: Implications for ethical guidelines. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35495. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Putting Women First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence against Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Researching, Documenting and Monitoring Sexual Violence in Emergencies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Measure | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Investigator developed | Pre-interview: gender, age, partner status, age when married, number of children, people in the household, education level, employment. |

| Prevalence of IPV | 10 items adapted from the short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale-2 [78] | Measure of both perpetration and victimization of IPV, including psychological aggression, physical assault, injury and destruction of property. Results represent report of at least one incident of IPV in the past year. |

| Acceptability of IPV | WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence, Women’s Questionnaire, Section 6 [3] | 10-item scale, Does a man have a good reason to hit his wife if…? Followed by a brief scenario (e.g., she does not complete housework to satisfaction). Respondents indicate “disagree” or “agree”. Cronbach’s alpha: Malaysia, pre: 0.86, post: 0.92; Lebanon, pre: 0.85, post: 0.67. |

| Beliefs about gender relations | 20 items adapted from Community Ideas about Gender Relations section of Attitude and Relationship Control Scales for Women’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence [79,80] | Measure of (1) respondents’ perceptions of community beliefs and (2) respondents’ personal beliefs. Includes four investigator-added items: My community thinks/I think…that if a woman is abused by her partner, this is her fate; that people experiencing abuse by their partners should keep it to themselves. Separate Community and Individual belief scales are presented (5-point response scale, 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). |

| Attitudes toward help-seeking | Three investigator-developed items assessing willingness to seek help for mental health and IPV victimization/perpetration | If you were… feeling very sad and overwhelmed by difficulties; being abused by your partner/found that you were using abusive behaviors with your partner …would you tell someone/seek help to try to change this behavior? (5-point scale, 1 = definitely no; 5 = definitely yes). |

| Mental health | 13 items from symptom checklist of Refugee Health Screener (RHS)-15 [81] | Measure of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder over the past two weeks (5-point scale, 0 = not at all; 4 = extremely). Cronbach’s alpha: Malaysia, pre: 0.91, post: 0.90; Lebanon, pre: 0.86, post: 0.91 |

| Functional impairment | Three investigator-developed items | Report of difficulty (1) Performing the tasks you need to do for your daily work; (2) Taking care of your family members; (3) Interacting with others socially over the past two weeks (3-point scale, 1 = not at all difficult; 3 = very difficult). |

| Social cohesion | Five items adapted from Samson, Raudenbush, and Earls [82] | E.g., People in this (Syrian/Rohingya) community are willing to help their neighbors (5-point scale, 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). |

| Self-efficacy | Five items adapted from the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale [83] | E.g., I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough (4-point scale, 1 = not at all true; 4 = exactly true). |

| Community-efficacy | Two investigator-developed items | (1) When confronted with relationship conflicts leading to violence, my community can find solutions; (2) Thanks to the resourcefulness of my community, we know how to handle unforeseen events such as violence arising from relationship conflicts (4-point scale, 1 = not at all true; 4 = exactly true). |

| Coping | Six items adapted from the Brief COPE [84], and four investigator-developed items | Brief COPE items presented as a composite variable. Investigator items assessing coping through violence and self-soothing presented separately (4-point scale). |

| Perceived workshop impact | Five investigator-developed items | Assessment of impact of workshop participation over the past few weeks (see items in Results section) (4-point scale, 1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). |

| Workshop satisfaction | 7-item satisfaction survey in Lebanon and a 6-item survey in Malaysia, both collected immediately after the workshop. | Satisfaction with clarity of information, communication of facilitators, training materials, questions answered, time of workshop, likelihood of advising others to participate in similar sessions or convey knowledge and skills to others (5-point scale, 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). |

| Reactions to research participation | Items from the Reactions to Research Participation Questionnaire (RRPQ) [85] | 12 items collected; for brevity’s sake, three items are presented (see items in Results section) (5-point scale, 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). |

| Malaysia | Lebanon | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | |

| Sample, n | 72 | 35 | 37 | 74 | 41 | 33 |

| Age, Mean (SD) Range | 31 (10.76) 18–59 | 30 (10.55) 18–56 | 32 (10.99) 18–59 | 34 (9.62) 18–61 | 33 (10.44) 18–61 | 35 (8.55) 21–51 |

| Partner status, married and living with partner, % (n/total n) | 65.3 (47/72) | 88.6 (31/35) | 43.2 (16/37) | 82.4 (61/74) | 78.0 (32/41) | 87.9 (29/33) |

| Age when married, Mean (SD) Range | 20 (6.12) 12–42 | 17(4.17) 12–29 | 24 (6.58) 15–42 | 22 (5.21) 14–35 | 19 (4.32) 14–32 | 25 (4.61) 14–35 |

| Number of children, Mean (SD) Range | 2.97 (2.58) 0–11 | 2.31 (1.89) 0–8 | 3.92 (3.15) 0–11 | 2.9 (2.64) 0–12 | 3.06 (2.63) 0–12 | 2.77 (2.67) 0–12 |

| Number of people in household, Mean (SD) Range | 6.07 (2.80) 2–14 | 5.83 (2.24) 2–10 | 2.92 (3.26) 1–5 | 5.47 (2.34) 1–12 | 5.71 (2.32) 2–12 | 5.18 (2.37) 1–10 |

| Employed, % (n/total n) | 59.7 (43/72) | 22.9 (8/35) | 94.6 (35/37) | 62.2 (46/74) | 58.5 (24/41) | 66.7 (22/33) |

| Education, primary or more % (n/total n) | 59.7 (43/72) | 45.7 (16/35) | 73.0 (27/37) | 87.8 (65/74) | 82.9 (34/41) | 93.9 (31/33) |

| Intimate Partner Violence Exposure (1 or More Instances in the Past Year) | ||||||

| Insulted, swore, shouted, or yelled | ||||||

| I did to my partner, % (n/total n) | 40.8 (29/71) | 31.4 (11/35) | 50.0 18/36) | 71.4 (50/70) | 65.8 (25/38) | 78.1 (25/32) |

| My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 43.7 (31/71) | 60.0 (21/35) | 27.8 (10/36) | 57.1 (40/70) | 60.5 (22/38) | 53.1 (17/32) |

| Sprain, bruise, cut, or felt pain the next day | ||||||

| I had because of fight with my partner, % (n/total n) | 22.5 (16/71) | 37.1 (13/35) | 8.3 (3/36) | 8.6 (6/70) | 15.8 (6/38) | 0.0 (0/32) |

| My partner had because of a fight with me, % (n/total n) | 4.2 (3/71) | 0.0 (0/35) | 8.3 (3/36) | 1.4 (1/70) | 2.6 (1/38) | 0.0 (0/32) |

| Pushed, shoved, or slapped | ||||||

| I did to my partner, % (n/total n) | 16.9 (12/71) | 11.4 (4/35) | 22.2 (8/36) | 14.3 (10/70) | 21.1 (8/38) | 6.3 (2/32) |

| My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 25.4 (18/71) | 45.7 (16/35) | 5.6 (2/36) | 10.0 (7/70) | 15.8 (6/38) | 3.1 (1/32) |

| Punched, kicked, or beat up | ||||||

| I did to my partner, % (n/total n) | 11.3 (8/71) | 0.0 (0/35) | 22.2 (8/36) | 1.4 (1/69) | 2.7 (1/37) | 0.0 (0/32) |

| My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 18.3 (13/71) | 37.1 (13/35) | 0.0 (0/36) | 2.9 (2/68) | 5.3 (2/38) | 0.0 (0/30) |

| Destroyed something belonging to my partner or threatened to hit my partner | ||||||

| I did to my partner, % (n/total n) | 7.0 (5/71) | 5.7 (2/35) | 8.3 (3/36) | 31.9 (22/69) | 35.1 (13/37) | 28.1 (9/32) |

| My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 11.3 (8/71) | 14.3 (5/35) | 8.3 (3/36) | 18.6 (13/70) | 26.3 (10/38) | 9.4 (3/32) |

| Variable | Wilcoxon Result, Z | |

|---|---|---|

| Malaysia | Lebanon | |

| Acceptability of violence a | 6.58 *** | 5.97 *** |

| Community ideas about gender relationships b (My perception of what my community believes) | 3.42 *** | −2.00 * |

| Individual ideas about gender relations (What I believe personally) | 7.28 *** | 5.13 *** |

| Help-seeking for mental health needs c | 3.88 *** | 5.25 *** |

| Help-seeking for victims of IPV | 5.84 *** | 3.95 *** |

| Help-seeking for perpetrators of IPV | 5.28 *** | 3.05 ** |

| Mental health (distress symptoms) | −6.08 *** | −6.82 *** |

| Functional impairment | −6.22 *** | −5.45 *** |

| Self-efficacy | 5.70 *** | 4.63 *** |

| Community efficacy d | 5.54 *** | 0.18 |

| Social cohesion d | 2.98 ** | 1.46 |

| Adaptive coping scale e | 6.16 *** | 4.50 *** |

| Coping by arguing/yelling (to deal with tension/stress) | −4.06 *** | −2.67 ** |

| Coping by hitting my partner (to deal with tension/stress) f | −0.42 | −2.17 * |

| Coping by hitting my children (to deal with tension/stress) g | −3.57 *** | −4.46 *** |

| Coping by using calming exercises (to deal with tension/stress) | 6.93 *** | 5.97 *** |

| Indicator | Measure | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Investigator developed | Same as Study 1 (see Table 1). |

| Prevalence of IPV | Adapted from the short form of Revised Conflict Tactics Scale-2 [78] | As in Study 1, 10 items used in Malaysia. In Lebanon, local team elected to use a subset of six items (see Table 5) to reduce interview length and resolve confusion over terminology in Arabic. Results indicate at least one incident of IPV in the past year. |

| Mental health | Symptom checklist from WASSS-6 [88] | 5-item scale assessing frequency of fear, anger, lack of interest, hopelessness, avoidance during the previous two weeks (5-point scale, 1 = none of the time; 5 = all of the time). Cronbach’s alpha: Malaysia, 0.79; Lebanon, 0.80. |

| Acceptability of IPV | WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence, Women’s Questionnaire, Section 6 [3] | Same as Study 1 (see Table 1). Cronbach’s alpha: Malaysia, 0.78; Lebanon, 0.76 |

| Beliefs about gender relations | Adapted from Community Ideas about Gender Relations section of the Attitude and Relationship Control Scales for Women’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence [79,80] | 16 items in Malaysia and 14-items in Lebanon. As in Study 1, four additional investigator-created items were included (see Table 1). Results presented from individual subscale only. |

| Relationship efficacy | Adapted from the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale [83] | Three items in Lebanon and five items in Malaysia adapted to apply to relationships (e.g., I can always manage to solve relationship problems if I try hard enough) (4-point scale, 1 = not at all true; 4 = exactly true). |

| Help-seeking intention, IPV victimization | Investigator developed item | If you were being abused by your partner, would you tell someone/seek help? using a 5-point response scale (1 = definitely no; 5 = definitely yes). |

| Help-seeking source preferences | Investigator developed item | Those indicating “yes” to the above question asked to indicate where they would seek help from a 9-item list. |

| IPV help-seeking and help-giving scenario | Investigator developed item | A vignette was read to participant: Now I will tell you a story… you hear Yusuf yelling at Rahima... Participants were asked to indicate what they would do and responses coded in a dropdown list. In Malaysia, participants also asked: Do you think Rahima will want to seek help? (Yes, Maybe, No). |

| Reactions to research participation | Items from the Reactions to Research Participation Questionnaire (RRPQ) [85] | Three items as in Study 1 (see Table 1). |

| Variable | Malaysia, n = 240 | Lebanon, n = 260 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women, n = 121 | Men, n = 119 | Women, n = 131 | Men, n = 129 | |

| Gender, % (n/grand total n) | 50.4 (121/240) | 49.6 (119/240) | 50.4 (131/260) | 49.6 (129/260) |

| Age, Mean (SD) Range | 31 (9.19) 18–58 | 32 (9.28) 19–61 | 32 (10.05) 18–65 | 37 (12.88) 18–65) |

| Partner status, married and living with partner, % (n/total n) | 88.4 (107/121) | 46.2 (55/119) | 82.4 (108/131) | 86.8 (112/129) |

| Age when married, Mean (SD), Range | 18 (5.15) 12–55 | 24 (5.73) 13–46 | 18 (4.20) 13–37 | 23 (4.64) 13–35 |

| How partner chosen, arranged a,b, % (n/total n) | 69.0(81/121) | 52.0 (43/88) | 55.4 (72/130) | 62.0 (70/113) |

| Number of children at home | 2.42 (1.63) 0–6 | 1.33 (1.43) 0–5 | 3.93 (2.46) 0–11 | 4.19 (2.69) 0–12 |

| Employed, % (n/total n) | 19.8 (24/121) | 88.2 (105/119) | 16.8 (22/131) | 2.3 (3/129) |

| Education, primary or more % (n/total n) | 55.4 (67/121) | 75.6 (90/119) | 19.1 (25/131) | 30.2 (39/129) |

| Time living in host country 1–5 years, % (n/total n) 5–10 years, % (n/total n) | 63.0 (75/120) 23.3 (28/120) | 57.1 (68/119) 41.2 (39/119) | 51.9 (68/131) 39.7 (52/131) | 50.4 (65/129) 42.6 (55/129) |

| Mental health, Mean, (SD) Range | 3.89 (1.01) 1–5 | 3.48 (0.90) 1–5 | 2.96 (1.27) 1–5 | 3.88 (0.76) 1.2–5 |

| Intimate Partner Violence exposure (1 or more instances in the past year), b,c,d % | ||||

| Insulted, swore, shouted, or yelled I did to my partner, % (n/total n) My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 31.4 (38/121) 46.3 (56/121) | 58.8 (70/119) 29.4 (35/119) | 20.0 (26/130) 40.0 (52/130) | 54.9 (62/113) 12.4 (14/113) |

| Sprain, bruise, cut, or felt pain the next day I had because of fight with my partner, % (n/total n) My partner had because of a fight with me, % (n/total n) | 24.0 (29/121) 0.0 (0/121) | 4.2 (5/119) 3.4 (4/119) | -- | -- |

| Pushed, shoved, or slapped I did to my partner, % (n/total n) My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 5.8 (7/120) 28.9 (35/121) | 23.5 (28/119) 2.5 (3/119) | 6.9 (9/130) 26.9 (35/130) | 25.7 (29/113) 0.9 (1/113) |

| Punched, kicked, or beat up I did to my partner, % (n/total n) My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 0.8 (1/120) 14.2 (17/120) | 9.2 (11/119) 1.7 (2/119) | -- | -- |

| Destroyed something belonging to my partner or threatened to hit my partner I did to my partner, % (n/total n) My partner did to me, % (n/total n) | 5.8 (7/121) 14.1 (17/121) | 12.6 (15/119) 6.7 (8/119) | 4.6 (6/130) 16.9 (22/130) | 6.2 (7/113) 2.6 (3/113) |

| Variables | Malaysia, n = 240 | Lebanon, n = 258 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Sample, n Poster condition, n; control condition, n | 121 59, 61 | 119 56, 63 | 130 63, 67 | 128 61, 67 |

| Acceptability of violence (scale) Odds Ratio, 95% CI | 0.60 ***, 0.47–0.76 | ns | Condition x gender interaction 0.57 ***, 0.41 to 0.79 | |

| Individual beliefs about gender relations (scale) Coefficient, 95% CI | ns | −0.12 ^ (p = 0.057), 0.25–0.00 | ns | |

| Relationship problem-solving efficacy (scale) Coefficient, 95% CI | 0.3 3 **, 0.08–0.58 | ns | Condition controlling for gender 0.21 *, 0.01–0.41 | |

| Help-seeking personal (if you were being abused, would you seek help?) Odds Ratio, 95% CI | 1.77 ^ (p = 0.097), 0.89–3.51 | ns | ns | |

| Help-seeking personal, sources (if you were being abused, who would you seek help from?) Odds Ratio, 95% CI | Religious Leaders: 2.14 *, 1.02–4.50 Social Institutions: 2.48 *, 1.20–5.13 | ns | Condition x gender interactions Family: 2.83 *, 1.04–7.69 Partner’s family: 0.17 ***, 0.06–0.49 | |

| Help-seeking beliefs (people experiencing abuse should keep it to themselves) a Odds Ratio, 95% CI | ns | ns | Condition controlling for gender 1.63 *, 1.04–2.56 | |

| Scenario: Help-seeking (Do you think woman will want to seek help?) Odds Ratio, 95% CI | 1.99 ^ (p = 0.051), 0.98–4.04 | ns | Item not used in Lebanon | |

| Scenario: Help-giving (React by not getting involved) Odds Ratio, 95% CI | 0.30 *, 0.11–0.83 | ns | Condition controlling for gender 0.64 ^ (p = 0.097), 0.38–1.09 | |

| Scenario: Help-giving (React by talking to couple) Odds Ratio, 95% CI | ns | ns | Condition x gender interaction Talk to wife: 0.35 *, 0.13–1.00 Condition controlling for gender Talk to husband: 1.80 *, 1.11–2.94 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

James, L.E.; Welton-Mitchell, C.; Michael, S.; Santoadi, F.; Shakirah, S.; Hussin, H.; Anwar, M.; Kilzar, L.; James, A. Development and Testing of a Community-Based Intervention to Address Intimate Partner Violence among Rohingya and Syrian Refugees: A Social Norms-Based Mental Health-Integrated Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111674

James LE, Welton-Mitchell C, Michael S, Santoadi F, Shakirah S, Hussin H, Anwar M, Kilzar L, James A. Development and Testing of a Community-Based Intervention to Address Intimate Partner Violence among Rohingya and Syrian Refugees: A Social Norms-Based Mental Health-Integrated Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111674

Chicago/Turabian StyleJames, Leah Emily, Courtney Welton-Mitchell, Saja Michael, Fajar Santoadi, Sharifah Shakirah, Hasnah Hussin, Mohammed Anwar, Lama Kilzar, and Alexander James. 2021. "Development and Testing of a Community-Based Intervention to Address Intimate Partner Violence among Rohingya and Syrian Refugees: A Social Norms-Based Mental Health-Integrated Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111674