The Sustained Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers One Year after the Outbreak—A Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey in a Tertiary Hospital of North-East Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Assessment Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Personal and Job Characteristics

3.2. Mental Health Outcomes 1 Year after the Pandemic Onset

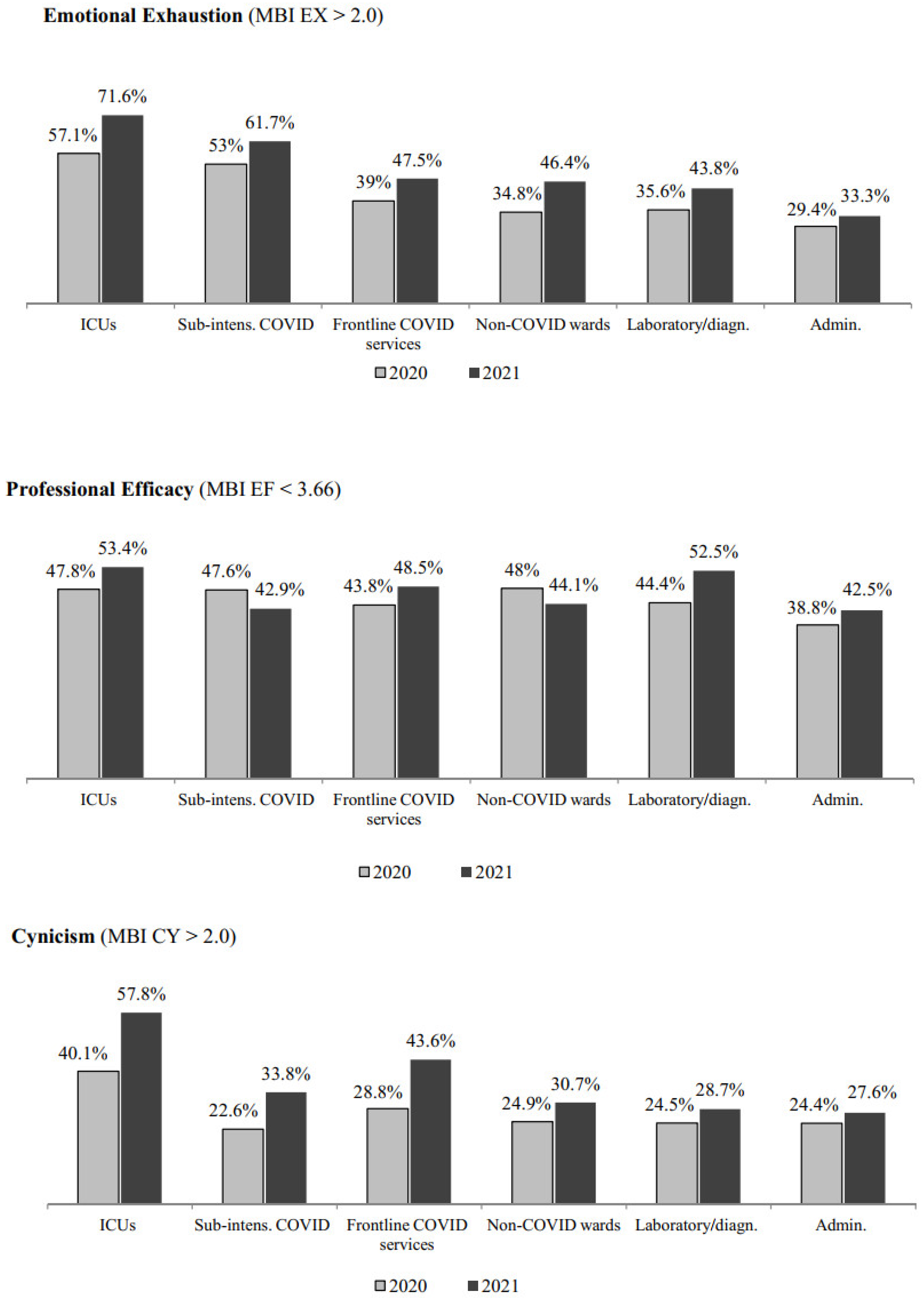

3.3. Differences in Adverse Mental Health Outcomes between 2020 and 2021

3.4. Risk Factors for Adverse Mental Health Outcomes 1 Year after the Pandemic Onset

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carmassi, C.; Foghi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Cordone, A.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Bui, E.; Dell’Osso, L. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.A.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C.M. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santabárbara, J.; Bueno-Notivol, J.; Lipnicki, D.M.; Olaya, B.; Pérez-Moreno, M.; Gracia-García, P.; Idoiaga-Mondragon, N.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N. Prevalence of anxiety in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review (on published articles in Medline) with meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 107, 110244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanghera, J.; Pattani, N.; Hashmi, Y.; Varley, K.F.; Cheruvu, M.S.; Bradley, A.; Burke, J.R. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting-A Systematic Review. J. Occup. Health 2020, 62, e12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Worker Wellness: A Scoping Review. West J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabarkapa, S.; Nadjidai, S.E.; Murgier, J.; Ng, C.H. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: A rapid systematic review. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 8, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, F.; Liu, H.L.; Yang, M.; Lu, C.L.; Dai, N.; Zhang, Y.; Robinson, N.; Liu, J.P. Immediate Psychosocial Impact on Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 645460. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, Q.H.; Chia, F.L.; Ng, W.K.; Lee, W.C.I.; Tan, P.L.L.; Wong, C.S.; Puah, S.H.; Shelat, V.G.; Seah, E.D.; Ceuey, C.W.T.; et al. Perceived Stress, Stigma, Traumatic Stress Levels and Coping Responses amongst Residents in Training across Multiple Specialties during COVID-19 Pandemic-A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Steenkiste, E.; Schoofs, J.; Gilis, S.; Messiaen, P. Mental health impact of COVID-19 in frontline healthcare workers in a Belgian Tertiary care hospital: A prospective longitudinal study. Acta Clin. Belg. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Steinmetz, L.C.; Herrera, C.R.; Fong, S.B.; Godoy, J.C. A Longitudinal Study on the Changes in Mental Health of Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ding, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Guo, Y.; Cheung, T.; Hall, B.J.; Shi, T.; Xiang, Y.T.; Tang, Y. Prevalence of poor psychiatric status and sleep quality among frontline healthcare workers during and after the COVID-19 outbreak: A longitudinal study. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Cui, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Gong, X.; Liu, J.; Wan, Z.; Yuan, X.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; et al. Nurses endured high risks of psychological problems under the epidemic of COVID-19 in a longitudinal study in Wuhan China. J. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 131, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Th’ng, F.; Rao, K.A.; Ge, L.; Mao, D.; Neo, H.N.; Molina, J.A.D.; Seow, E. A One-Year Longitudinal Study: Changes in Depression and Anxiety in Frontline Emergency Department Healthcare Workers in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N.; Soave, P.M.; Antonelli, M. A One-Year Prospective Study of Work-Related Mental Health in the Intensivists of a COVID-19 Hub Hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasalvia, A.; Bonetto, C.; Porru, S.; Carta, A.; Tardivo, S.; Bovo, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Amaddeo, F. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. Epidemiol. Psychiatry Sci. 2020, 30, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasalvia, A.; Amaddeo, F.; Porru, S.; Carta, A.; Tardivo, S.; Bovo, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Bonetto, C. Levels of burn-out among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital of a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Keane, T.M., Eds.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer, M.; Bell, R.; Failla, S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale-revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zung, W.W.K. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 1971, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.A.; Scott, N. Norms for Zung’s Self-rating Anxiety Scale. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatry Ann. 2002, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. In The Maslach Burnout Inventory, 3rd ed.; Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lasalvia, A.; Bonetto, C.; Bertani, M.; Bissoli, S.; Cristofalo, D.; Marrella, G.; Ceccato, E.; Cremonese, C.; De Rossi, M.; Lazzarotto, L.; et al. Influence of perceived organisational factors on job burnout: Survey of community mental health staff. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N.; Soave, P.M.; Antonelli, M. Prolonged Stress Causes Depression in Frontline Workers Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study in a COVID-19 Hub-Hospital in Central Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Nucera, G.; Szarpak, L. COVID-19 mortality in Italy: The first wave was more severe and deadly, but only in Lombardy region. J. Infect. 2021, 83, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, M. Disputes in the management of COVID-19 infected subjects. Health Prim. Care 2021, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletti, M.; Pancrazi, R. Geographic Negative Correlation of Estimated Incidence between First and Second Waves of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. Mathematics 2021, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, M.; Arienti, R.; Bini, F.; Bodini, B.D.; Corbetta, E.; Gianturco, L. Differences between the waves in Northern Italy: How the characteristics and the outcome of COVID-19 infected patients admitted to the emergency room have changed. J. Infect. 2021, 83, e32–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Al-Lenjawi, B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 141, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Sinigaglia, T.; Lo Moro, G.; Rousset, S.; Cremona, A.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. The Burden of Burnout among Healthcare Professionals of Intensive Care Units and Emergency Departments during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, K.J. Professional Stigma of Mental Health Issues: Physicians Are Both the Cause and Solution. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijeratne, C.; Johnco, C.; Draper, B.; Earl, J. Doctors’ reporting of mental health stigma and barriers to help-seeking. Occup. Med. 2021, 71, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.K.; Quinn, S.M.; Danley, A.L.; Wiens, K.J.; Mehta, J.J. Burnout and Perceptions of Stigma and Help-Seeking Behavior Among Pediatric Fellows. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021050393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Leep Hunderfund, A.N.; Winters, R.C.; Moeschler, S.M.; Vaa Stelling, B.E.; Dozois, E.J.; Satele, D.V.; West, C.P. The Relationship Between Burnout and Help-Seeking Behaviors, Concerns, and Attitudes of Residents. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Health, F.; Thompson, R. A Meta-Analysis of Response Rates in Web- or Internet-Based Survey. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.T.; Quan, H.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Noseworthy, T.; Beck, C.A.; Dixon, E.; Samuel, S.; Ghali, W.A.; Sykes, L.L.; Jetté, N. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khatatbeh, M.; Alhalaiqa, F.; Khasawneh, A.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Khatatbeh, H.; Alhassoun, S.; Al Omari, O. The Experiences of Nurses and Physicians Caring for COVID-19 Patients: Findings from an Exploratory Phenomenological Study in a High Case-Load Country. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Vega, B.; Palao, Á.; Muñoz-Sanjose, A.; Torrijos, M.; Aguirre, P.; Fernández, A.; Amador, B.; Rocamora, C.; Blanco, L.; Marti-Esquitino, J. Implementation of a Mindfulness-Based Crisis Intervention for Frontline Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Outbreak in a Public General Hospital in Madrid, Spain. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 562578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (19 missing) | ||

| Male | 234 | 23.1 |

| Female | 780 | 76.9 |

| Age (years) (3 missing) | ||

| <36 | 332 | 32.2 |

| 36–55 | 503 | 48.8 |

| >55 | 195 | 18.9 |

| Occupation (11 missing) | ||

| Physicians | 138 | 13.5 |

| Residents | 171 | 16.7 |

| Nurses | 379 | 36.7 |

| Other health care staff | 233 | 22.6 |

| Administrative staff | 101 | 9.8 |

| Work place (40 missing) | ||

| Intensive care units | 135 | 13.6 |

| Sub-intensive COVID-19 wards 1 | 157 | 15.8 |

| Frontline services dealing with COVID-19 2 | 114 | 11.5 |

| Non-COVID-19 wards | 400 | 40.3 |

| Laboratory diagnostic services 3 | 88 | 8.9 |

| Administration | 99 | 10.0 |

| . | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| HCWs having had received MH treatment (10 missing) | ||

| Yes | 86 | 8.4 |

| No | 937 | 91.6 |

| HCWs still in MH treatment (10 missing) | ||

| Yes | 59 | 68.6 |

| No | 27 | 31.4 |

| Type of mental health provider (10 missing) | ||

| Private | 59 | 68.6 |

| Public | 27 | 31.4 |

| Type of MH intervention received (10 missing) | ||

| Pharmacological treatment | 9 | 10.5 |

| Psychotherapy | 40 | 46.5 |

| Both | 24 | 27.9 |

| Other | 13 | 15.1 |

| Perceived efficacy of MH treatment (11 missing) | ||

| Yes | 76 | 89.4 |

| No | 9 | 10.6 |

| First Assessment | Second Assessment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Rank | n | % | Rank | Δ Rank | |

| High number of deaths, patients dying alone, use of telephone to communicate the death of loved ones | 73 | 18.9 | 3 | 71 | 31.1 | 1 | +2 |

| Feeling under pressure due to time and staff constraints | 102 | 26.4 | 1 | 56 | 24.6 | 2 | −1 |

| Fear of being infected and/or infecting others | 82 | 21.2 | 2 | 25 | 11.0 | 3 | −1 |

| Insufficient supervision, unclear guidelines, shortage of PPE | 44 | 11.4 | 4 | 20 | 8.8 | 4 | 0 |

| Reassigned to a COVID-19 unit | 31 | 8.0 | 5 | 15 | 6.6 | 5 | 0 |

| Infection or death of a relative, friend or colleague | 13 | 3.4 | 8 | 14 | 6.1 | 6 | +2 |

| Difficult ethical decisions in a short time | 16 | 4.1 | 6 | 12 | 5.3 | 7 | −1 |

| Being infected with COVID-19 | 14 | 3.6 | 7 | 9 | 3.9 | 8 | −1 |

| Difficulty of balancing work and family life | 11 | 2.8 | 9 | 6 | 2.6 | 9 | 0 |

| 386 | 100.0 | 228 | 100.0 | ||||

| Post-Traumatic Distress * (n = 335) | Anxiety (n = 932) | Depression (n = 917) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <24 IES-R n (%) | ≥24 IES-R n (%) | p | <36 SAS n (%) | ≥36 SAS n (%) | p | <10 PHQ n (%) | ≥10 PHQ n (%) | p | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 22 (31.9) | 47 (68.1) | 0.364 | 129 (62.9) | 76 (37.1) | <0.001 | 142 (70.0) | 61 (30.0) | <0.001 |

| Female | 69 (26.1) | 195 (73.9) | 273 (38.5) | 437 (61.5) | 389 (55.7) | 309 (44.3) | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <36 | 41 (36.9) | 70 (63.1) | 0.030 | 146 (47.7) | 160 (52.3) | 0.038 | 176 (58.7) | 124 (41.3) | 0.321 |

| 36–55 | 38 (22.8) | 129 (77.2) | 177 (39.9) | 267 (60.1) | 252 (57.8) | 184 (42.2) | |||

| >55 | 14 (24.6) | 43 (75.4) | 88 (48.9) | 92 (51.1) | 115 (64.2) | 64 (35.8) | |||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Physicians | 18 (36.0) | 32 (64.0) | 0.143 | 79 (62.2) | 48 (37.8) | <0.001 | 90 (70.9) | 37 (29.1) | <0.001 |

| Residents | 18 (34.6) | 34 (65.4) | 80 (51.6) | 75 (48.4) | 91 (59.5) | 62 (40.5) | |||

| Nurses | 31 (21.2) | 115 (78.8) | 102 (30.5) | 232 (69.5) | 164 (50.2) | 163 (49.8) | |||

| Other health care staff | 22 (31.9) | 47 (68.1) | 96 (44.9) | 118 (55.1) | 130 (61.9) | 80 (38.1) | |||

| Administrative staff | 3 (21.4) | 11 (78.6) | 49 (53.3) | 43 (46.7) | 65 (72.2) | 25 (27.8) | |||

| Work place | |||||||||

| Intensive care units | 16 (23.9) | 51 (76.1) | 0.870 | 41 (34.2) | 79 (65.8) | 0.006 | 49 (41.9) | 68 (58.1) | <0.001 |

| Sub-intensive COVID-19 wards 1 | 27 (30.7) | 61 (69.3) | 50 (35.2) | 92 (64.8) | 75 (54.7) | 62 (45.3) | |||

| Frontline services dealing with COVID-19 2 | 10 (22.7) | 34 (77.3) | 54 (51.9) | 50 (48.1) | 59 (56.7) | 45 (43.3) | |||

| Non-COVID-19 wards | 27 (30.3) | 62 (69.7) | 178 (49.7) | 180 (50.3) | 228 (64.6) | 125 (35.4) | |||

| Laboratory diagnostic services 3 | 6 (31.6) | 13 (68.4) | 35 (43.8) | 45 (56.3) | 47 (58.8) | 33 (41.3) | |||

| Administration | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | 42 (46.2) | 49 (53.8) | 65 (73.0) | 24 (27.0) | |||

| Experienced traumatic event | |||||||||

| Yes | 93 (27.8) | 242 (72.2) | - | 78 (23.6) | 253 (76.4) | <0.001 | 123 (37.8) | 202 (62.2) | <0.001 |

| No | - | - | 335 (55.7) | 266 (44.3) | 422 (71.3) | 170 (28.7) | |||

| Emotional Exhaustion (n = 897) | Professional Efficacy (n = 897) | Cynicism (n = 897) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2.20 n (%) | >2.20 n (%) | p | ≥3.66 n (%) | <3.66 n (%) | p | ≤2.00 n (%) | >2.00 n (%) | p | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 113 (56.5) | 87 (43.5) | 0.016 | 113 (56.5) | 87 (43.5) | 0.404 | 126 (63.0) | 74 (37.0) | 0.791 |

| Female | 319 (46.8) | 362 (53.2) | 362 (53.2) | 319 (46.8) | 436 (64.0) | 245 (36.0) | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <36 | 146 (49.3) | 150 (50.7) | 0.158 | 145 (49.0) | 151 (51.0) | 0.063 | 189 (63.9) | 107 (36.1) | 0.664 |

| 36–55 | 201 (47.4) | 223 (52.6) | 231 (54.5) | 193 (45.5) | 267 (63.0) | 157 (37.0) | |||

| >55 | 98 (56.0) | 77 (44.0) | 105 (60.0) | 70 (40.0) | 117 (66.9) | 58 (33.1) | |||

| Work place | |||||||||

| Intensive care units | 33 (28.4) | 83 (71.6) | <0.001 | 54 (46.6) | 62 (53.4) | 0.342 | 49 (42.2) | 67 (57.8) | <0.001 |

| Sub-intensive COVID-19 wards 1 | 51 (38.3) | 82 (61.7) | 76 (57.1) | 57 (42.9) | 88 (66.2) | 45 (33.8) | |||

| Wards/services dealing with COVID-19 2 | 53 (52.5) | 48 (47.5) | 52 (51.5) | 49 (48.5) | 57 (56.4) | 44 (43.6) | |||

| Non-COVID-19 wards | 185 (53.6) | 160 (46.4) | 193 (55.9) | 152 (44.1) | 239 (69.3) | 106 (30.7) | |||

| Laboratory diagnostic services 3 | 45 (56.3) | 35 (43.8) | 38 (47.5) | 42 (52.5) | 57 (71.3) | 23 (28.7) | |||

| Administration | 58 (66.7) | 29 (33.3) | 50 (57.5) | 37 (42.5) | 63 (72.4) | 24 (27.6) | |||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Physicians | 68 (54.8) | 56 (45.2) | <0.001 | 78 (62.9) | 46 (37.1) | 0.002 | 86 (69.4) | 38 (30.6) | <0.001 |

| Residents | 77 (51.7) | 72 (48.3) | 61 (40.9) | 88 (59.1) | 99 (66.4) | 50 (336) | |||

| Nurses | 130 (40.2) | 193 (59.8) | 169 (52.3) | 154 (47.7) | 177 (54.8) | 146 (45.2) | |||

| Other health care staff | 109 (53.7) | 94 (46.3) | 119 (58.6) | 84 (41.4) | 142 (70.0) | 61 (30.0) | |||

| Administrative staff | 59 (67.0) | 29 (33.0) | 50 (56.8) | 38 (43.2) | 65 (73.9) | 23 (26.1) | |||

| Experienced traumatic event | |||||||||

| No | 361 (62.2) | 219 (37.8) | <0.001 | 316 (54.5) | 264 (45.5) | 0.605 | 418 (72.1) | 162 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 84 (26.5) | 233 (73.5) | 167 (52.7) | 150 (47.3) | 157 (49.5) | 160 (50.5) | |||

| Post-Traumatic Distress | Anxiety | Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj OR (95% CI) | p | Adj OR (95% CI) | p | Adj OR (95% CI) | p | ||||

| Category | Overall LR Test | Category | Overall LR Test | Category | Overall LR Test | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 1 | 0.300 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.007 | |||

| Female | 1.40 (0.74–2.66) | 0.296 | 2.40 (1.66–3.47) | <0.001 | 1.68 (1.15–2.45) | 0.007 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <36 | 1 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.130 | 1 | 0.569 | |||

| 36–55 | 2.86 (1.42–5.76) | 0.003 | 1.45 (0.95–2.22) | 0.082 | 1.25 (0.82–1.91) | 0.290 | |||

| >55 | 3.05 (1.25–7.44) | 0.014 | 1.08 (0.65–1.80) | 0.762 | 1.19 (0.71–1.99) | 0.510 | |||

| Work place | |||||||||

| Intensive care units | 1 | 0.441 | 1 | 0.094 | 1 | 0.099 | |||

| Sub-intensive COVID-19 wards | 0.53 (0.24–1.18) | 0.119 | 0.95 (0.53–1.70) | 0.856 | 0.50 (0.29–0.88) | 0.015 | |||

| Frontline wards/services | 0.89 (0.34–2.30) | 0.805 | 0.58 (0.31–1.06) | 0.074 | 0.65 (0.36–1.17) | 0.149 | |||

| Non-COVID-19 wards | 0.51 (0.23–1.14) | 0.103 | 0.86 (0.52–1.43) | 0.569 | 0.57 (0.35–0.92) | 0.022 | |||

| Laboratory diagnostic services | 0.47 (0.13–1.70) | 0.252 | 1.25 (0.62–2.54) | 0.535 | 0.78 (0.39–1.56) | 0.488 | |||

| Administration | 0.31 (0.06–1.56) | 0.156 | 1.79 (0.74–4.32) | 0.197 | 0.40 (0.17–0.96) | 0.041 | |||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Physician | 1 | 0.203 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.034 | |||

| Resident | 2.04 (0.74–5.65) | 0.170 | 1.88 (1.00–3.54) | 0.051 | 2.00 (1.04–3.81) | 0.036 | |||

| Nurse | 2.03 (0.92–4.46) | 0.078 | 3.08 (1.87–5.07) | <0.001 | 2.14 (1.30–3.54) | 0.003 | |||

| Other health care staff | 1.07 (0.45–2.51) | 0.882 | 1.65 (0.98–2.78) | 0.061 | 1.42 (0.83–2.44) | 0.200 | |||

| Administrative staff | 3.69 (0.54–25.15) | 0.182 | 0.99 (0.42–2.31) | 0.974 | 1.58 (0.67–3.75) | 0.296 | |||

| Experienced traumatic event | |||||||||

| No | - | - | - | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | - | - | 4.42 (3.13–6.25) | <0.001 | 3.74 (2.72–5.14) | <0.001 | |||

| Number of observations | 319 | 874 | 860 | ||||||

| LR test | χ2(12) = 18.94 | χ2(13) = 165.58 | χ2(13) = 120.02 | ||||||

| p | 0.090 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Pearson goodness-of-fit | |||||||||

| Number of covariate patterns | 77 | 170 | 170 | ||||||

| χ2(df) | χ2(64) = 62.36 | χ2(156) = 174.11 | χ2(156) = 169.31 | ||||||

| p | 0.535 | 0.153 | 0.220 | ||||||

| Area under ROC curve | 0.641 | 0.742 | 0.709 | ||||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | Professional Efficacy | Cynicism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj OR (95% CI) | p | Adj OR (95% CI) | p | Adj OR (95% CI) | p | ||||

| Category | Overall LR Test | Category | Overall LR Test | Category | Overall LR Test | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 1 | 0.097 | 1 | 0.492 | 1 | 0.589 | |||

| Female | 1.36 (0.94–1.96) | 0.098 | 1.13 (0.80–1.59) | 0.492 | 0.90 (0.63–1.30) | 0.588 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <36 | 1 | 0.364 | 1 | 0.564 | 1 | 0.619 | |||

| 36–55 | 1.29 (0.85–1.96) | 0.235 | 1.22 (0.82–1.80) | 0.329 | 1.15 (0.75–1.76) | 0.511 | |||

| >55 | 1.04 (0.63–1.72) | 0.880 | 1.07 (0.66–1.73) | 0.783 | 1.29 (0.77–2.16) | 0.329 | |||

| Work place | |||||||||

| Intensive care units | 1 | 0.037 | 1 | 0.152 | 1 | 0.004 | |||

| Sub-intensive COVID-19 wards | 0.56 (0.31–1.01) | 0.053 | 0.68 (0.40–1.15) | 0.155 | 0.35 (0.20–0.61) | <0.001 | |||

| Frontline wards/Services | 0.39 (0.21–0.72) | 0.003 | 0.88 (0.58–1.54) | 0.660 | 0.64 (0.37–1.13) | 0.123 | |||

| Non-COVID-19 wards | 0.50 (0.30–0.83) | 0.008 | 0.71 (0.44–1.12) | 0.142 | 0.43 (0.30–0.70) | 0.001 | |||

| Laboratory diagnostic services | 0.44 (0.22–0.88) | 0.021 | 1.32 (0.68–2.54) | 0.407 | 0.48 (0.24–0.96) | 0.037 | |||

| Administration | 0.34 (0.14–0.81) | 0.015 | 0.68 (0.30–1.50) | 0.339 | 0.46 (0.20–1.08) | 0.076 | |||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Physician | 1 | 0.585 | 1 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.115 | |||

| Resident | 1.21 (0.65–2.27) | 0.542 | 2.95 (1.62–5.37) | <0.001 | 1.33 (0.70–2.54) | 0.384 | |||

| Nurse | 1.40 (0.86–2.28) | 0.178 | 1.56 (0.98–2.49) | 0.060 | 1.70 (1.04–2.79) | 0.036 | |||

| Other health care staff | 1.12 (0.66–1.88) | 0.676 | 1.01 (0.61–1.67) | 0.971 | 1.06 (0.62–1.82) | 0.835 | |||

| Administrative staff | 0.90 (0.39–2.08) | 0.815 | 1.52 (0.69–3.33) | 0.299 | 1.02 (0.43–2.43) | 0.960 | |||

| Experienced traumatic event | |||||||||

| No | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.895 | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 3.91 (2.82–5.42) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.75–1.39) | 0.895 | 2.41 (1.75–3.30) | <0.001 | |||

| Number of observations | 842 | 842 | 842 | ||||||

| LR test | χ2(13) = 127.09 | χ2(13) = 29.03 | χ2(13) = 72.51 | ||||||

| p | <0.001 | 0.006 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Pearson goodness-of-fit | |||||||||

| Number of covariate patterns | 169 | 169 | 169 | ||||||

| χ2(df) | χ2(155) = 166.68 | χ2(155) = 157.00 | χ2(155) = 161.08 | ||||||

| p | 0.247 | 0.440 | 0.352 | ||||||

| Area under ROC curve | 0.717 | 0.606 | 0.668 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lasalvia, A.; Bodini, L.; Amaddeo, F.; Porru, S.; Carta, A.; Poli, R.; Bonetto, C. The Sustained Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers One Year after the Outbreak—A Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey in a Tertiary Hospital of North-East Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413374

Lasalvia A, Bodini L, Amaddeo F, Porru S, Carta A, Poli R, Bonetto C. The Sustained Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers One Year after the Outbreak—A Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey in a Tertiary Hospital of North-East Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413374

Chicago/Turabian StyleLasalvia, Antonio, Luca Bodini, Francesco Amaddeo, Stefano Porru, Angela Carta, Ranieri Poli, and Chiara Bonetto. 2021. "The Sustained Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers One Year after the Outbreak—A Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey in a Tertiary Hospital of North-East Italy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413374

APA StyleLasalvia, A., Bodini, L., Amaddeo, F., Porru, S., Carta, A., Poli, R., & Bonetto, C. (2021). The Sustained Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers One Year after the Outbreak—A Repeated Cross-Sectional Survey in a Tertiary Hospital of North-East Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13374. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413374