Moderating Effects of Structural Empowerment and Resilience in the Relationship between Nurses’ Workplace Bullying and Work Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Workplace Bullying

1.2. Nursing and Workplace Bullying

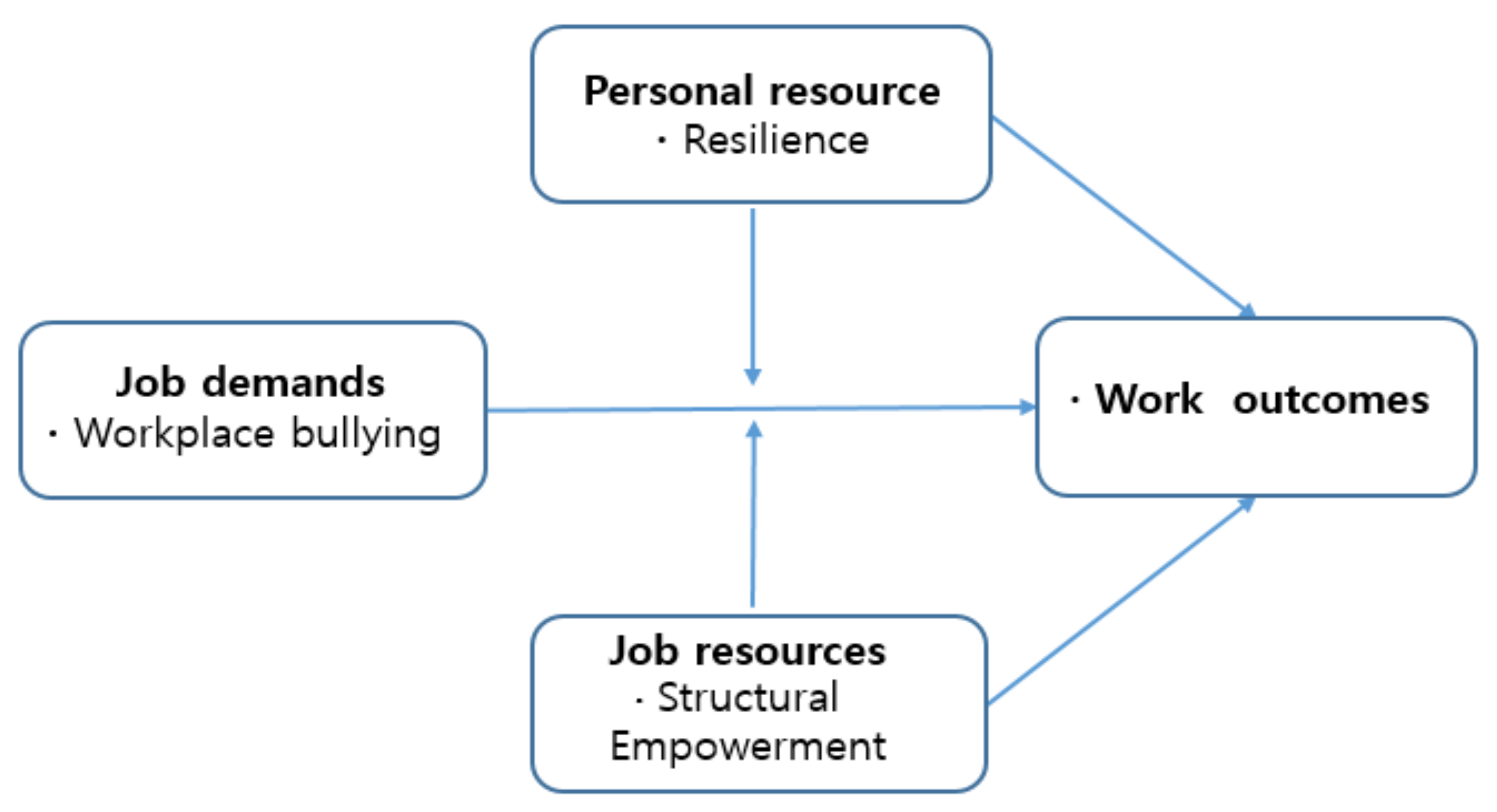

1.3. Workplace Bullying and the Job Demands–Resources Model

1.4. Structural Empowerment and Resilience

1.5. Study Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Experience of Workplace Bullying

2.3.2. Structural Empowerment

2.3.3. Resilience

2.3.4. Work Outcomes

2.3.5. General Characteristics

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Experiences of Workplace Bullying

3.3. The Moderating Effects of Structural Empowerment and Resilience on the Relationship between Bullying and Nursing Work Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Experiences of Workplace Bullying and Nursing Work Outcomes

4.2. The Moderating Effect of Structural Empowerment on the Relationship between Workplace Bullying and Nursing Work Outcomes

4.3. The Moderating Effect of Resilience on the Relationship between Bullying and Nursing Work Outcomes

4.4. Research Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessey, J.A.; Demarco, R.; DiFazio, R. Bullying, Harassment, and Horizontal Violence in the Nursing Workforce The State of the Science. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2010, 28, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P.; Tracy, S.J.; Alberts, J.K. Burned by bullying in the American workplace: Prevalence, perception, degree and impact. J. Manag. 2007, 44, 837–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.; Jackson, D.; Wilkes, L.; Vickers, M. A new model of bullying in the nursing workplace. Organizational characteristics as critical antecedents. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2008, 31, E60–E71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sune, C.J.; Jung, M.S. Concept Analysis of Workplace Bullying in Nursing. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2014, 8, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.Y.; Cheon, J.Y.; Seo, T.J.; Jung, S.G. Prevention of Workplace Bullying among Women Workers: Survey Analysis and Policy Suggestions; Korean Women’s Development Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, J.; Sherman, R.O. Leveling horizontal violence. Nurs. Manag. 2007, 38, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embree, J.L.; White, A.H. Concept analysis: Nurse-to-nurse lateral violence. Nurs. Forum 2010, 45, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J. Personal and work-group incivility: Impact on work and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, C.; Diers, D.; O’Brien-Pallas, L.; Aisbett, C.; Roche, M.; King, M.; Aisbett, K. Nursing staffing, nursing workload, the work environment and patient outcomes. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2011, 24, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Grau, A.L.; Finegan, J.; Wilk, P. Predictors of new graduate nurses’ workplace well-being: Testing the job demands—Resources model. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands—Resources model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; De Boer, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Taris, T.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Schreurs, P. A multi-group analysis of the Job Demands-Resources model in four home care organizations. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2003, 10, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espen, O.; Gunhild, B.; Aslaug, M. Work climate and the mediating role of workplace bullying related to job performance, job satisfaction, and work ability: A study among hospital nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2709–2719. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R.M. Men and Women of the Corporation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, S.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Wong, C.A. The influence of empowerment, authentic leadership, and professional practice environments on nurses’ perceived interprofessional collaboration. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, E54–E61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.; Avey, J.; Norman, S. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gillespie, B.M.; Chaboyer, W.; Wallis, M.; Grimbeck, P. Resilience in the operating room: Developing and testing of a resilience model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 59, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnon, T. Understanding How Resiliency Development Influences Adolescent Bullying and Victimization. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 25, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, E.; Laschinger, H.K. Correlates of New Graduate Nurses’ Experiences of Workplace Mistreatment. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2013, 43, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Lee, M.H. The conceptual development and development of new instruments to measure bullying in nursing workplace. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2014, 44, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work Stress 2009, 23, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Finegan, J.; Shamian, J. Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings: Expanding Kanter’s model. J. Nurs. Adm. 2001, 31, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baek, H.S.; Lee, K.U.; Joo, E.J.; Lee, M.Y.; Choi, K.S. Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (K-CD-RISC). Psychiatry Investig. 2010, 7, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ko, Y.K.; Lee, T.W.; Lim, J.Y. Development of a Performance Measurement Scale for Hospital Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2007, 37, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, K.O.; Park, S.A.; Park, S.H.; Lee, E.H.; Kim, M.A.; Kwag, W.H. Revision of performance appraisal tool and verification of reliability and validity. J. Korean Clin. Nurs. Res. 2011, 17, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H. Effect of Nursing Work Environment and Resilience on Nursing Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School, Kosin University, Busan, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Park, I.S. The Relationships among Nursing Workload, Nurse Manager’s Social Support, Nurses’ Psychosocial Health and Job Satisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2016. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.W. A Study to Develop a Scale of Social Support. Ph.D. Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, 1985. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.M.; Kim, D.H. Moderating effects of Professional Self-concept in Relationship between Workplace Bullying and Nursing Service Quality among Hospital Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. Adm. 2018, 24, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.; Vickers, M.H.; Wilkes, L.; Jackson, D. A typology of bullying behaviors: The experiences of Australian nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 2319–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attell, B.K.; Brown, K.K.; Treiberc, L.A. Workplace bullying, perceived job stressors, and psychological distress: Gender and race differences in the stress process. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 65, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, L. Portrait of a Modern Nurse Survey; RN Network: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S. Related Factor of Physicians’ and Nurses’ Attitudes toward and Intentions behind Reporting. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, M.; Bernstein, K. Effect of Workplace Bullying and Job Stress on Turnover Intention in Hospital Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 22, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reknes, I.; Pallesen, S.; Magerøy, N.; Moen, B.E.; Bjorvatn, B.; Einarsen, S. Exposure to bullying behaviors as a predictor of mental health problems among Norwegian nurses: Results from the prospective SUSSH-survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.Y.; Rho, H.J.; Lee, J.H. The Impact of Organizational Justice, Empowerment on the Nursing Task Performance of Nurses: Focused on the Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. Korean J. Occup. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Fida, R. Linking nurses’ perceptions of patient care quality to job satisfaction: The role of authentic leadership and empowering professional practice environments. J. Nurs. Adm. 2015, 45, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, T.; Regan, S.; Laschinger, H.K.S. The influence of empowerment and incivility on the mental health of new graduate nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balevre, S.M.; Park, S.B.; David, J.C. Nursing professional development anti-bullying project. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2018, 34, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, E.A.; Laschinger, H.K.S. The influence of authentic leadership and empowerment on nurses’ relational social capital, mental health and job satisfaction over the first year of practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, H.; Han, K.; Ryu, E. Authentic leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: The moderating effect of nurse tenure. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, M.; Stuart, W. Resilience to bullying: Towards an alternative to the anti-bullying approach. J. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2017, 33, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brian, M.; Stuart, W. Resilience, Bullying, and Mental Health: Factors associated with improved outcomes. Psychol. Sch. 2017, 54, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, L.A.; Perhats, C.; Clark, P.R.; Moon, M.D.; Zavotsky, K.E. Workplace bullying in emergency nursing: Development of a grounded theory using situational analysis. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 39, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Raphael, D.; Mackay, L.; Smith, M.; King, A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, A.B. ‘Hierarchy of Controls’: Providing a framework for addressing workplace hazards. Am. J. Nurs. 2003, 103, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsen, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Hetland, J.; Olsen, O.K.; Zahlquist, L.; Mikkelsen, E.G.; Koløen, J.; Einarsen, S.V. Outcomes of a Proximal Workplace Intervention Against Workplace Bullying and Harassment: A Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Among Norwegian Industrial Workers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, M.; McKinnon, J. The importance of teaching and learning resilience in the health disciplines: A critical review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Classification | n | (%) | M ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <29 | 190 | (43.7) | 32.64 ± 6.85 | |

| 30–39 | 178 | (40.9) | |||

| 40–49 | 53 | (12.2) | |||

| ≥50 | 14 | (3.2) | |||

| Gender | Female | 410 | (94.3) | ||

| Male | 25 | (5.7) | |||

| Marital status | Single | 311 | (71.5) | ||

| Married | 124 | (28.5) | |||

| Position | Staff nurse | 391 | (89.9) | ||

| Charge nurse | 29 | (6.7) | |||

| Unit manager | 15 | (3.4) | |||

| Years of work experience | 1 | 25 | (5.7) | ||

| 1–<3 | 92 | (21.1) | |||

| 3–<5 | 97 | (22.3) | 7.49 ± 6.76 | ||

| 5–<10 | 104 | (23.9) | |||

| ≥10 | 117 | (26.9) | |||

| Years at current workplace | 1 | 50 | (11.5) | ||

| 1–<3 | 132 | (30.3) | |||

| 3–<5 | 116 | (26.7) | 4.37 ± 3.89 | ||

| 5–<10 | 96 | (22.1) | |||

| ≥10 | 41 | (9.4) | |||

| Work department | Ward | 225 | (51.7) | ||

| Intensive care unit | 122 | (28.0) | |||

| Emergency room | 34 | (7.8) | |||

| Operating room | 54 | (12.4) | |||

| Witnessed bullying during the total working period | Yes | 300 | (69.0) | ||

| No | 135 | (31.0) | |||

| Subjective workload | Overall | 3.34 ± 0.55 | 1–5 | ||

| Ward | 3.28 ± 0.54 | ||||

| Intensive care unit | 3.40 ± 0.52 | ||||

| Emergency room | 3.28 ± 0.67 | ||||

| Operating room | 3.48 ± 0.58 | ||||

| Social support | Overall | 2.82 ± 0.45 | 1–4 | ||

| Ward | 2.87 ± 0.43 | ||||

| Intensive care unit | 2.74 ± 0.45 | ||||

| Emergency room | 2.97 ± 0.56 | ||||

| Operating room | 2.69 ± 0.41 | ||||

| Experience of workplace bullying | Overall | 1.84 ± 0.58 | 1–4 | ||

| Work related bullying | 2.09 ± 0.71 | ||||

| Verbal/non-verbal bullying | 1.84 ± 0.69 | ||||

| External threats | 1.27 ± 0.51 | ||||

| Overall | 3.77 ± 0.49 | 1–5 | |||

| Nursing work outcomes | Nursing performance ability | 3.99 ± 0.51 | |||

| Attitude towards nursing | 3.88 ± 0.56 | ||||

| Nursing support function | 3.91 ± 0.61 | ||||

| Improving the level of nursing | 3.28 ± 0.81 | ||||

| Application of the nursing process | 3.71 ± 0.71 | ||||

| Structural empowerment | 3.09 ± 0.54 | 1–5 | |||

| Resilience | 3.34 ± 0.48 | 1–5 | |||

| Characteristics | Categories | Experience of Workplace Bullying | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | t/F | Scheffe | ||

| (p) | ||||

| Age | <29 (a) | 1.95 ± 0.59 | 4.703 | b < a |

| 30–39 (b) | 1.73 ± 0.54 | (<0.01) | ||

| 40–49 (c) | 1.81 ± 0.59 | |||

| ≥50 (d) | 1.87 ± 0.62 | |||

| Gender | Female | 1.84 ± 0.58 | −0.468 | - |

| Male | 1.89 ± 0.59 | (0.64) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 1.88 ± 0.57 | 2.119 | - |

| Married | 1.75 ± 0.59 | (0.04) | ||

| Position | Staff nurse | 1.84 ± 0.58 | 0.061 | - |

| Charge nurse | 1.83 ± 0.59 | (0.94) | ||

| Unit manager | 1.79 ± 0.53 | |||

| Years of total RN experience | 1 (a) | 1.93 ± 0.62 | 4.488 | d < b |

| 1–<3 (b) | 2.04 ± 0.55 | (<0.01) | ||

| 3–<5 (c) | 1.84 ± 0.61 | |||

| 5–<10 (d) | 1.71 ± 0.56 | |||

| ≥10 (e) | 1.79 ± 0.56 | |||

| Years at current workplace | 1(a) | 1.82 ± 0.58 | 2.127 | - |

| 1–<3 (b) | 1.93 ± 0.58 | (0.08) | ||

| 3–<5 (c) | 1.82 ± 0.59 | |||

| 5–<10 (d) | 1.72 ± 0.55 | |||

| ≥10 (e) | 1.91 ± 0.58 | |||

| Work department | Ward (a) | 1.75 ± 0.55 | 6.93 | a, c < d |

| Intensive care unit (b) | 1.91 ± 0.58 | (<0.01) | ||

| Emergency room (c) | 1.74 ± 0.64 | |||

| Operating room (d) | 2.11 ± 0.58 | |||

| Witnessed bullying during the total working period | Yes | 1.95 ± 0.58 | 6.043 | - |

| No | 1.60 ± 0.50 | (<0.01) | ||

| Explanatory Variables | Nursing Work Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||

| β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Experience of workplace bullying (X) | −0.033 | −0.626 | −0.009 | −0.175 | −0.012 | −0.235 |

| Structural empowerment (M1) | 0.300 | 6.108 *** | 0.306 | 6.231 *** | ||

| X * M1 | −0.068 | −1.649 | ||||

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Experience of workplace bullying (X) | −0.033 | −0.626 | −0.057 | −1.167 | −0.058 | −1.18 |

| Resilience (M2) | 0.378 | 8.884 *** | 0.375 | 8.646 *** | ||

| X * M2 | 0.010 | 0.239 | ||||

| Nursing Work Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | B | Boot SE | 95% CI of B |

| Structural empowerment | |||

| Low (mean − 1SD) | −0.074 | 0.051 | −0.175~0.028 |

| Mean | −0.138 | 0.039 | −0.215~−0.061 |

| High (mean + 1SD) | −0.203 | 0.054 | −0.308~−0.097 |

| Resilience | |||

| Low (mean − 1SD) | −0.190 | .049 | −0.287~−0.093 |

| Mean | −0.173 | .036 | −0.244~−0.102 |

| High (mean + 1SD) | −0.156 | .046 | −0.246~−0.065 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, H.; Han, K. Moderating Effects of Structural Empowerment and Resilience in the Relationship between Nurses’ Workplace Bullying and Work Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041431

Kang H, Han K. Moderating Effects of Structural Empowerment and Resilience in the Relationship between Nurses’ Workplace Bullying and Work Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041431

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Heiyoung, and Kihye Han. 2021. "Moderating Effects of Structural Empowerment and Resilience in the Relationship between Nurses’ Workplace Bullying and Work Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041431