Is Fitspiration the Healthy Internet Trend It Claims to Be? A British Students’ Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The difference in fit-ideal internalisation after fitspiration exposure.

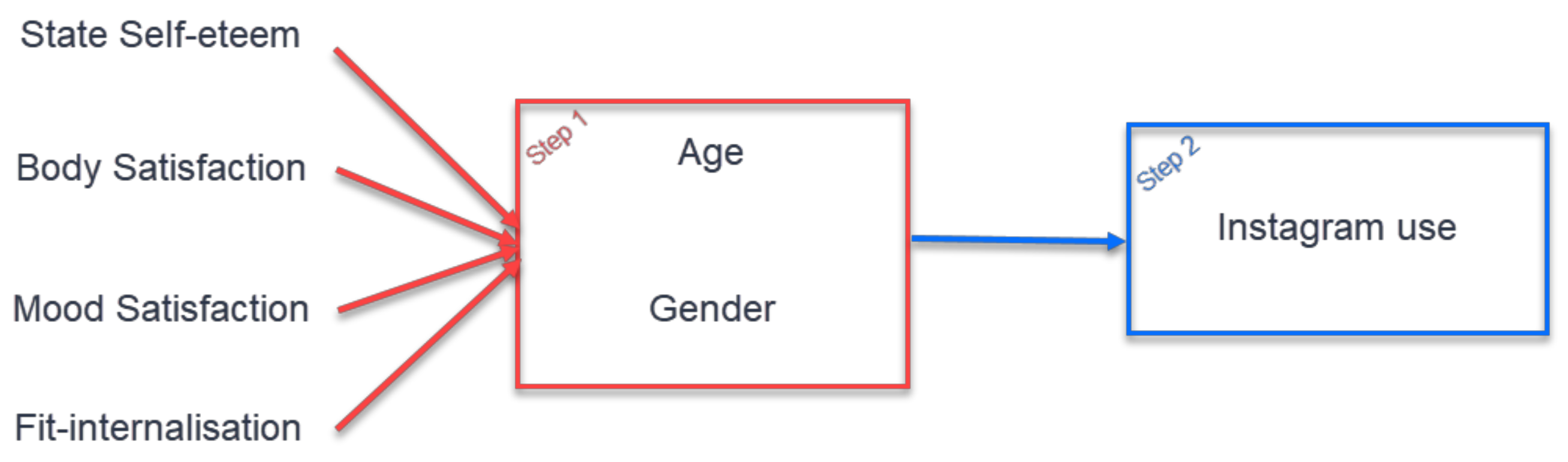

- The association between gender, age and Instagram usage, with state self-esteem (SSE), mood satisfaction, body satisfaction and fit-ideal internalization.

- The association between Instagram usage factors (the number of Instagram followers, the number of people followed, the number of photos posted, the frequency of Instagram use and the importance of a photo’s “likes”) with SSE, mood and body satisfaction and fit-ideal internalisation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Experimental Conditions

2.2. Questionnaire

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grogan, S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M.; Rothblum, E.D. Gender Differences in Internal Beliefs About Weight and Negative Attitudes Towards Self and Others. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Frederick, D.A.; Aavik, T.; Alcalay, L.; Allik, J.; Anderson, D.; Andrianto, S.; Arora, A.; Brännström, Å.; Cunningham, J.; et al. The Attractive Female Body Weight and Female Body Dissatisfaction in 26 Countries Across 10 World Regions: Results of the International Body Project, I. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swami, V.; Tovée, M.J. Female physical attractiveness in Britain and Malaysia: A cross-cultural study. Body Image 2005, 2, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, E.M.; Dittmar, H.; Ayers, S. The impact of cosmetic surgery advertising on women’s body image and at-attitudes towards cosmetic surgery. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2017, 6, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boepple, L.; Thompson, J.K. A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, J.-P.; Krause, E.; Ohler, P. Every (Insta)Gram counts? Applying cultivation theory to explore the effects of Instagram on young users’ body image. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2021, 10, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image 2015, 13, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabe, A.G.; Forney, K.J.; Keel, P.K. Do you “like” my photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, E.P.; Gray, J. Facebook Photo Activity Associated with Body Image Disturbance in Adolescent Girls. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frison, E.; Eggermont, S. Browsing, Posting, and Liking on Instagram: The Reciprocal Relationships Between Different Types of Instagram Use and Adolescents’ Depressed Mood. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.; Newton-John, T.; Slater, A. ‘Selfie’-objectification: The role of selfies in self-objectification and disordered eating in young women. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 79, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, S.; Ward, L.M.; Hyde, J.S. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M.; Zaccardo, M. “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image 2015, 15, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, L.R.; Donovan, C.L.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Bell, H.S.; Ramme, R.A. The fit beauty ideal: A healthy alternative to thinness or a wolf in sheep’s clothing? Body Image 2018, 25, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.; Stefanovski, A. Thinspiration and fitspiration in everyday life: An experience sampling study. Body Image 2019, 30, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, I.; Kavanagh, E.; Mulgrew, K.E.; Lim, M.S.; Tiggemann, M. The effect of Instagram #fitspiration images on young women’s mood, body image, and exercise behaviour. Body Image 2020, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaterlaus, J.M.; Patten, E.V.; Roche, C.; Young, J.A. #Gettinghealthy: The perceived influence of social media on young adult health behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deighton-Smith, N.; Bell, B.T. Objectifying fitness: A content and thematic analysis of #fitspiration images on social media. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2018, 7, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prichard, I.; McLachlan, A.C.; Lavis, T.; Tiggemann, M. The Impact of Different Forms of #fitspiration Imagery on Body Image, Mood, and Self-Objectification among Young Women. Sex Roles 2018, 78, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Prichard, I.; Nikolaidis, A.; Drummond, C.; Drummond, M.; Tiggemann, M. Idealised media images: The effect of fitspiration imagery on body satisfaction and exercise behaviour. Body Image 2017, 22, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, A.; Varsani, N.; Diedrichs, P.C. #fitspo or #loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram images on women’s body image, self-compassion, and mood. Body Image 2017, 22, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M.; Zaccardo, M. ‘Strong is the new skinny’: A content analysis of# fitspiration images on Instagram. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Carrotte, E.R.; Prichard, I.; Lim, M.S.C. “Fitspiration” on social media: A content analysis of gendered images. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Keery, H.; Berg, P.V.D.; Thompson, J. An evaluation of the Tripartite Influence Model of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance with adolescent girls. Body Image 2004, 1, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shroff, H.; Thompson, J.K. The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A replication with adolescent girls. Body Image 2006, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingoia, J.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Wilson, C.; Gleaves, D.H. The Relationship between Social Networking Site Use and the Internalization of a Thin Ideal in Females: A Meta-Analytic Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Tod, D.; Molnar, G.; Markland, D. Perceived social pressures and the internalization of the mesomorphic ideal: The role of drive for muscularity and autonomy in physically active men. Body Image 2016, 16, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stratton, R.; Donovan, C.; Bramwell, S.; Loxton, N.J. Don’t stop till you get enough: Factors driving men towards muscularity. Body Image 2015, 15, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. “Strong beats skinny every time”: Disordered eating and compulsive exercise in women who post fitspiration on Instagram. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C.C.G.; Neufeld, J.M.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R. Drive for thinness and drive for muscularity: Opposite ends of the continuum or separate constructs? Body Image 2010, 7, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, P.G.; Rai, J. The Generation Z and their social media usage: A review and a research outline. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2017, 9, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, M.J.; Kim, H.; Matthews, W.J. Age differences in social comparison tendency and personal relative deprivation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 87, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J. Factors affecting the frequency and amount of social networking site use: Motivations, perceptions, and privacy concerns. First Monday 2010, 15, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanVoorhis, C.R.; Morgan, B. Understanding Power and Rules of Thumb for Determining Sample Sizes. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Polivy, J. Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; van de Berg, P.; Roehrig, M.; Guarda, A.S.; Heinberg, L.J. The sociocultural attitudes towards appearance scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 35, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinberg, L.J.; Thompson, J.K. Body image and televised images of thinness and attractiveness: A controlled laboratory investigation. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 14, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggatt, M.; Wright, C.J.C.; Carrotte, E.; Jenkinson, R.; Mulgrew, K.; Prichard, I.; Lim, M.S.C. “I aspire to look and feel healthy like the posts convey”: Engagement with fitness inspiration on social media and perceptions of its influence on health and wellbeing. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F.; Smolak, L. Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fardouly, J.; Willburger, B.K.; Vartanian, L.R. Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 1380–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, B.; Turner, M.; Udell, J. Add a comment … how fitspiration and body positive captions attached to social media images influence the mood and body esteem of young female Instagram users. Body Image 2020, 33, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M.; Hayden, S.; Brown, Z.; Veldhuis, J. The effect of Instagram “likes” on women’s social comparison and body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2018, 26, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.A.; Paxton, S.J.; Wertheim, E.H. Does Media Literacy Mitigate Risk for Reduced Body Satisfaction Following Exposure to Thin-Ideal Media? J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1678–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.F.; McLean, S.A.; Paxton, S.J. When Seeing Is Not Believing: An Examination of the Mechanisms Ac-counting for the Protective Effect of Media Literacy on Body Image. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, H.-V.; Baum, K.; Baumann, A.; Krasnova, H. Unifying the detrimental and beneficial effects of social network site use on self-esteem: A systematic literature review. Media Psychol. 2019, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, C.-C.; Brown, B.B. Online Self-Presentation on Facebook and Self Development During the College Transition. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hum, N.J.; Chamberlin, P.E.; Hambright, B.L.; Portwood, A.C.; Schat, A.C.; Bevan, J.L. A picture is worth a thousand words: A content analysis of Facebook profile photographs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1828–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, B.; Twenge, J.M.; Freeman, E.C.; Campbell, W.K. The effect of social networking websites on positive self-views: An experimental investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1929–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L.; Prestin, A.; So, J. Facebook friends with (health) benefits? Exploring social network site use and perceptions of social support, stress, and well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Toma, C.L.; Hancock, J.T. Self-Affirmation Underlies Facebook Use. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, H.S.; Donovan, C.L.; Ramme, R. Is athletic really ideal? An examination of the mediating role of body dissatisfaction in predicting disordered eating and compulsive exercise. Eat. Behav. 2016, 21, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamplin, N.C.; McLean, S.A.; Paxton, S.J. Social media literacy protects against the negative impact of exposure to appearance ideal social media images in young adult women but not men. Body Image 2018, 26, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassiakos, Y.R.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Media, C.O.C.A. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perloff, R.M. Social Media Effects on Young Women’s Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles 2014, 71, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before | After | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Self-Esteem (SSE) | 3.15(±0.69) | 3.06(±0.79) | F(1, 108) = 9.18, p = 0.003, np2 = 0.078 |

| Mood Satisfaction | 5.50(±1.73) | 5.19(±1.84) | F(1, 108) = 13.68, p < 0.05, np2 = 0.112 |

| Body Satisfaction | 5.11(±1.57) | 4.99(±1.61) | F(1,107) = 2.39, p = 0.125, np2 = 0.022 |

| Fit-ideal Internalisation | 1.43(±0.31) | 1.39(±0.33) | F(1, 108) = 8.48, p = 0.004, np2 = 0.073 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Limniou, M.; Mahoney, C.; Knox, M. Is Fitspiration the Healthy Internet Trend It Claims to Be? A British Students’ Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041837

Limniou M, Mahoney C, Knox M. Is Fitspiration the Healthy Internet Trend It Claims to Be? A British Students’ Case Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041837

Chicago/Turabian StyleLimniou, Maria, Charlotte Mahoney, and Megan Knox. 2021. "Is Fitspiration the Healthy Internet Trend It Claims to Be? A British Students’ Case Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041837