Assessment of Quality of Life in Infertility Treated Women in Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Groups

2.2. Abbreviated World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF)

2.3. Fertility Quality of Life Tool (FertiQoL)

2.4. Statistical Methods

- Pearson’s chi-square test to compare the categorical variables between study groups;

- F test for analysis of variance to compare continuous variables between study groups and the least significant difference test was used as post hoc test.

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

- 400 women were treated without the use of assisted reproductive technology techniques (non-ART),

- 400 were treated using the intrauterine insemination method (IUI),

- 400 women were treated with the use of in vitro fertilization (IVF).

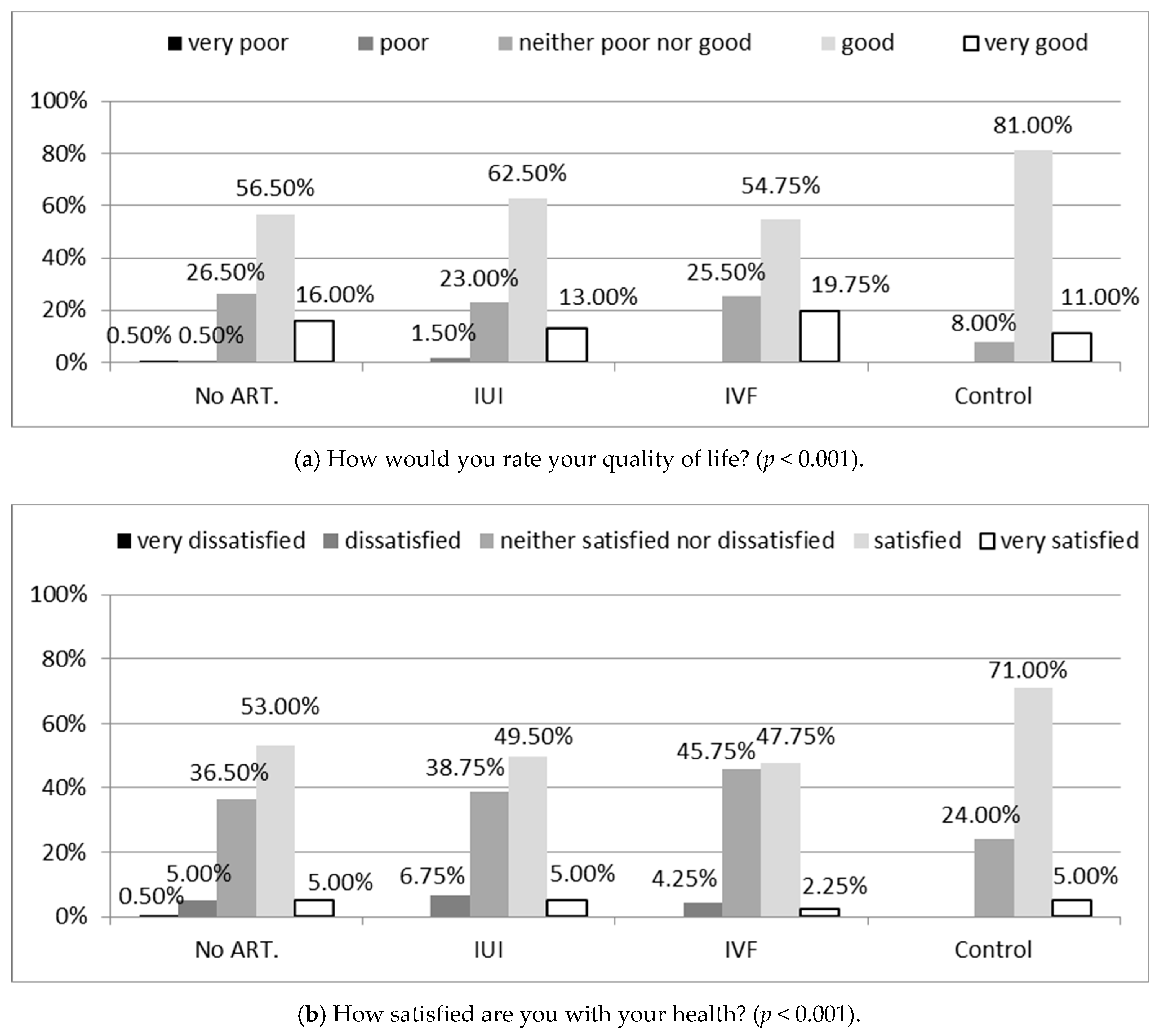

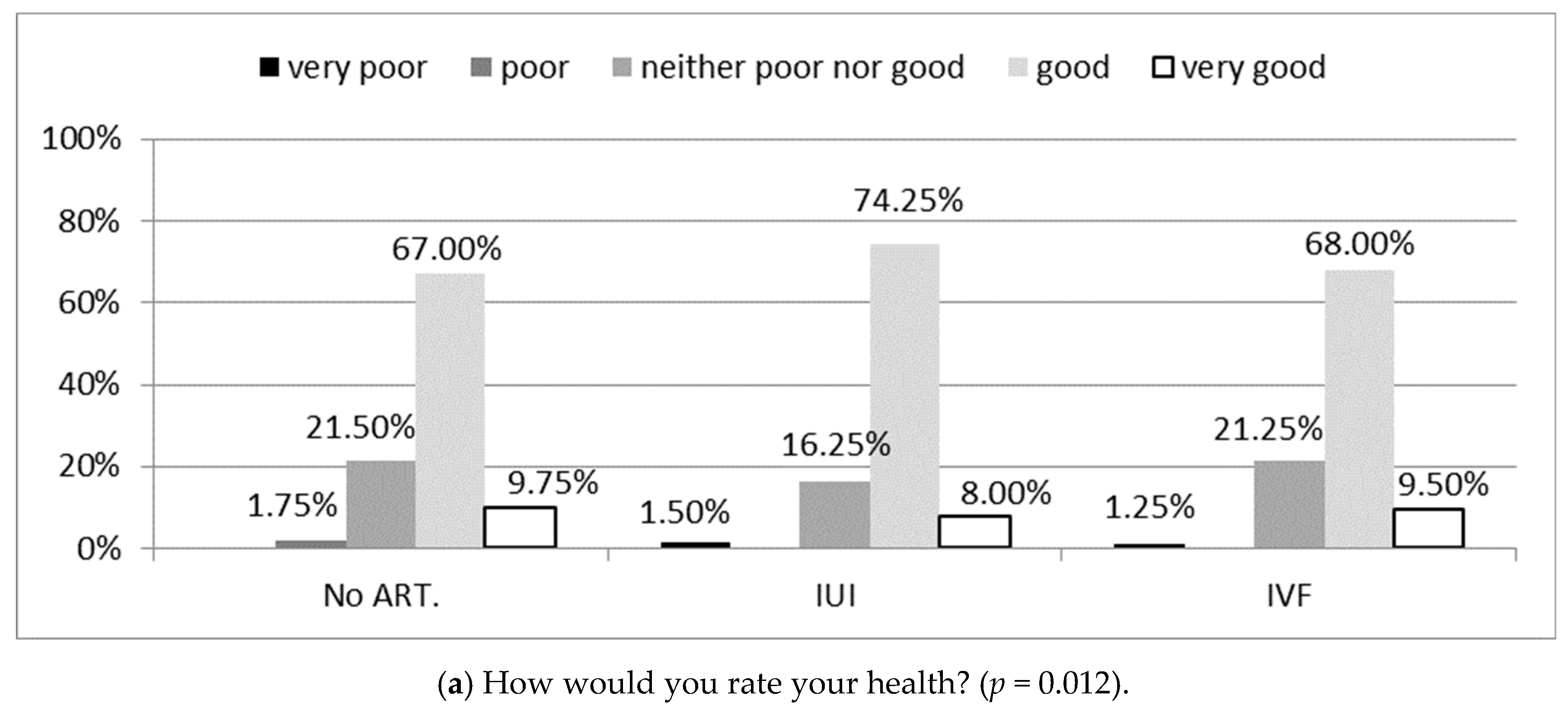

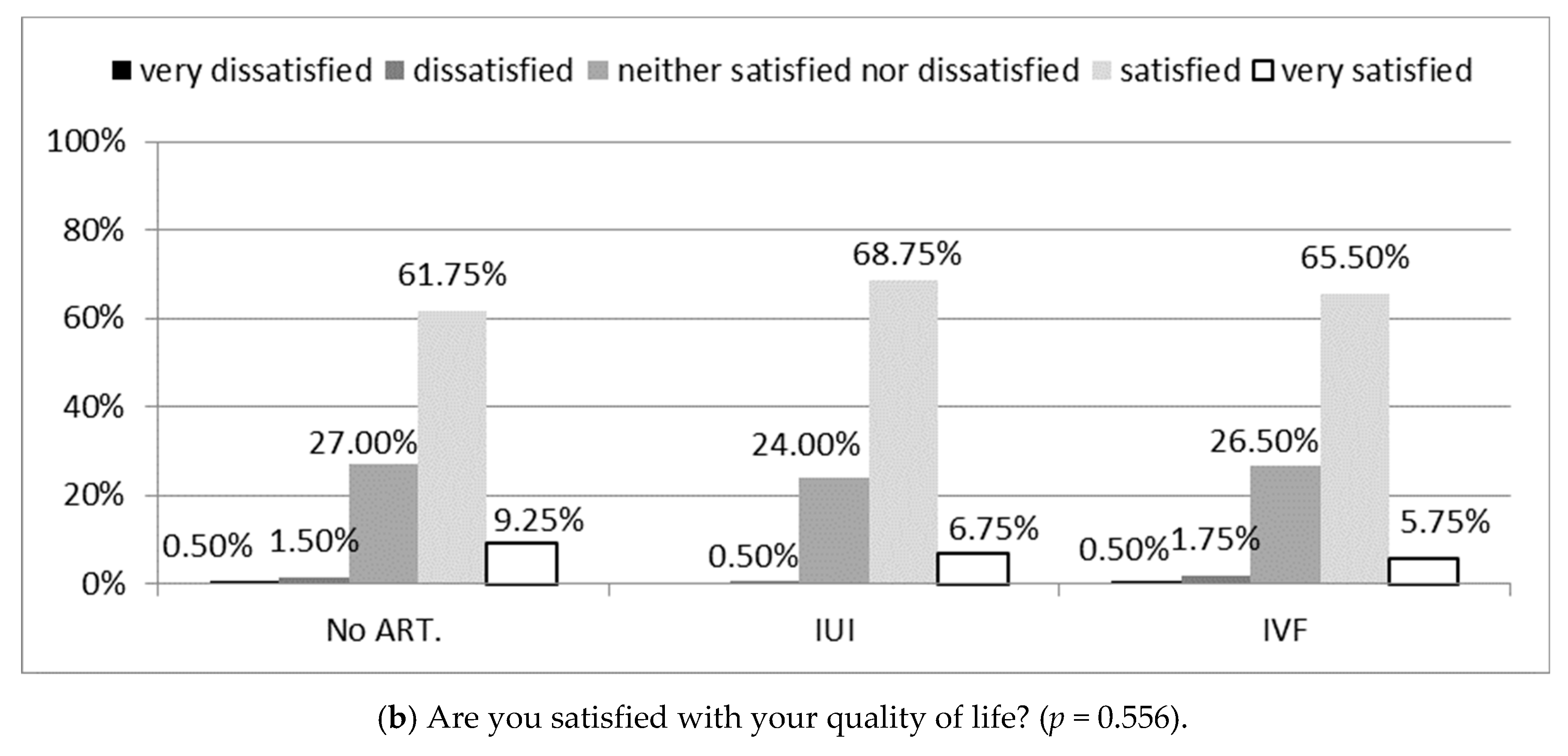

3.2. Comparison of the Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) between Respondents with Infertility and Those Who Had Children

3.3. Quality of Life According to the FertiQoL versus Method of Infertility Treatment

3.4. Correlations between Quality of Life According to FertiQoL and Characteristics of the Study Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Reproductive problems can influence the quality of life of affected women.

- Prolongation of the time of infertility treatment negatively affects the quality of life of women undergoing therapy.

- The quality of life of patients treated due to infertility depends on their age, place of residence, and education level.

- Intellectual work, on permanent basis, without burden of hazardous factors, exerts a favourable effect on the evaluation of the quality of life of women treated due to infertility.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strzelecki, Z.; Gałązka, A.; Jakimiuk, A.; Issat, T.; Korbasińska, D.; Kowalska, I.; Kurkiewicz, J.; Kuropka, I.; Anacka, M.; Potrykowska, A.; et al. Sytuacja Demograficzna Polski; Rządowa Rada Ludnościowa: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Kornas-Biela, D. Oblicza Macierzyństwa; Wyd. KUL: Lublin, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Telka, E. Ocena jakości życia w wymiarze psychologicznym, zdrowotnym i społecznym. Nowa Med. 2013, 4, 184–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dembińska, A. Partnership relations in infertility treatment. Med. Ogólna Nauk. Zdrowiu 2015, 21, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makara-Studzińska, M.; Morylowska-Topolska, J.; Wdowiak, A.; Bakalczuk, G.; Bakalczuk, S. Lȩk i depresja u kobiet leczonych z powodu niepłodności. Prz. Menopauzalny 2010, 6, 414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Makara-Studzinśka, M.; Wdowiak, A.; Bakalczuk, G.; Bakalczuk, S.; Krys, K. Emotional problems among couples treated for infertility Problemy emocjonalne wśród par leczonych z powodu niepłodności. Seksuologia Pol. 2012, 10, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Podolska, M.Z.; Bidzan, M. Infertility as a psychological problem. Ginekol. Pol. 2011, 82, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, J.; Takefman, J.; Braverman, A. The fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) tool: Development and general psychometric properties. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 2084–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zegers-Hochschild, F.; Adamson, G.D.; de Mouzon, J.; Ishihara, O.; Mansour, R.; Nygren, K.; Sullivan, E.; Vanderpoel, S. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009∗. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 1520–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaracz, K.; Kalfoss, M.; Górna, K.; Bączyk, G. Quality of life in Polish respondents: Psychometric properties of the Polish WHOQOL–Bref. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2006, 20, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, J.; Takefman, J.; Braverman, A. The Fertility Quality of Life (FertiQoL) tool: Development and general psychometric properties. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 409–415.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexty, R.E.; Hamadneh, J.; Rösner, S.; Strowitzki, T.; Ditzen, B.; Toth, B.; Wischmann, T. Cross-cultural comparison of fertility specific quality of life in German, Hungarian and Jordanian couples attending a fertility center. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrmann, D.; Scherg, H.; Verres, R.; Von Hagens, C.; Strowitzki, T.; Wischmann, T. Resilience in infertile couples acts as a protective factor against infertility-specific distress and impaired quality of life. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2011, 28, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aarts, J.W.M.; Van Empel, I.W.H.; Boivin, J.; Nelen, W.L.; Kremer, J.A.M.; Verhaak, C.M. Relationship between quality of life and distress in infertility: A validation study of the Dutch FertiQoL. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolczuk, E. Niepłodność, tożsamość, obywatelstwo. Analiza społecznej mobilizacji wokół dostępu do in vitro w Polsce. In Etnografie Biomedycyny; The University of Warsaw Press: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rzońca, E.; Bień, A.; Wdowiak, A.; Szymański, R.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G. Determinants of quality of life and satisfaction with life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rzońca, E.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Bień, A.; Wdowiak, A.; Szymański, R.; Chołubek, G. Generalized self-efficacy, dispositional optimism, and illness acceptance in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bień, A.; Rzońca, E.; Zarajczyk, M.; Wilkosz, K.; Wdowiak, A.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: A cross-sectional survey. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.Y.; Lin, M.W.; Hwang, J.L.; Lee, M.S.; Wu, M.H. The fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) questionnaire in Taiwanese infertilecouples. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 52, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chi, H.J.; Park, I.H.; Sun, H.G.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, K.H. Psychological distress and fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) in infertile Korean women: The first validation study of Korean FertiQoL. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2016, 43, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufizadeh, S.; Ghaheri, A.; Omani Samani, R. Factors associated with poor quality of life among Iranian infertile women undergoing IVF. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramat, A.; Masoumi, S.Z.; Mousavi, S.A.; Poorolajal, J.; Shobeiri, F.; Hazavehie, S.M.M. Quality of life and its related factors in infertile couples. J. Res. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, A.; Özkan, S.; Oǧuz, N. Predictors of fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) in infertile women: Analysis of confounding factors. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 170, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexty, R.E.; Griesinger, G.; Kayser, J.; Lallinger, M.; Rösner, S.; Strowitzki, T.; Toth, B.; Wischmann, T. Psychometric characteristics of the FertiQoL questionnaire in a German sample of infertile individuals and couples. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raque-Bogdan, T.L.; Hoffman, M.A. The Relationship among Infertility, Self-Compassion, and Well-Being for Women with Primary or Secondary Infertility. Psychol. Women Q. 2015, 39, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable, Parameter | IU or Category | Infertility Treated Women | Control Group (N = 100) | Comparison between Groups p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ART (N = 400) | IUI (N = 400) | IVF (N = 400) | ||||

| Age, Min–Max, M ± SD | years | 20–43, 32.7 ± 4.4 | 22–44, 32.4 ± 4.5 | 24–42, 33.2 ± 4.0 | 27–43, 33.7 ± 4.4 | 0.007 |

| Place of residence, n (%) | city | 162 (40.50) | 162 (40.50) | 158 (39.50) | 51 (51.00) | 0.050 |

| town | 101 (25.25) | 91 (22.75) | 100 (25.00) | 21 (21.00) | ||

| rural area | 137 (34.25) | 147 (36.75) | 142 (35.50) | 28 (28.00) | ||

| Level of education, n (%) | basic vocational | 25 (6.25) | 5 (1.25) | 30 (7.50) | 0 (0.00) | <0.001 |

| secondary | 99 (24.75) | 96 (24.00) | 94 (23.50) | 19 (19.00) | ||

| tertiary | 276 (69.00) | 299 (74.75) | 276 (69.00) | 81 (81.00) | ||

| BMI, Min–Max, M ± SD | kg/m2 | 15.4–37.2, 24.2 ± 4.1 | 16.4–38.9, 24.0 ± 4.7 | 15.2–37.8, 24.5 ± 4.3 | 17.7–37.1, 25.2 ± 5.5 | 0.083 |

| BMI, n (%) | underweight | 20 (5.00) | 31 (7.75) | 15 (3.75) | 4 (4.00) | 0.007 |

| normal weight | 249 (62.25) | 234 (58.50) | 257 (64.25) | 50 (50.00) | ||

| overweight | 90 (22.50) | 85 (21.25) | 82 (20.50) | 22 (22.00) | ||

| obesity | 41 (10.25) | 50 (12.50) | 46 (11.50) | 24 (24.00) | ||

| Having children, n (%) | yes, from the current relationship | 39 (9.75) | 40 (10.00) | 23 (5.75) | 100 (100.00) | <0.001 * |

| yes, from a previous relationship | 48 (12.00) | 18 (4.50) | 28 (7.00) | |||

| no | 313 (78.25) | 342 (85.50) | 349 (87.25) | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Time to get pregnant, Min–Max, M ± SD | years | 1–10, 3.4 ± 2.1 | 1–9, 3.2 ± 2.1 | 1–10, 3.6 ± 2.0 | - | 0.090 |

| Mode of employment, n (%) | manual | 91 (22.75) | 78 (19.50) | 97 (24.25) | 14 (14.00) | 0.281 |

| non-manual | 195 (48.75) | 215 (53.75) | 196 (49.00) | 57 (57.00) | ||

| mixed | 114 (28.50) | 107 (26.75) | 107 (26.75) | 29 (29.00) | ||

| Type of employment, n (%) | constant | 183 (45.75) | 226 (56.50) | 187 (46.75) | 58 (58.00) | 0.010 |

| shift | 129 (32.25) | 89 (22.25) | 123 (30.75) | 22 (22.00) | ||

| not normalized | 88 (22.00) | 85 (21.25) | 90 (22.50) | 20 (20.00) | ||

| Monthly net income per 1 person (thousand PLN), n (%) | below 1 | 38 (9.50) | 27 (6.75) | 29 (7.25) | 2 (2.00) | 0.001 |

| 1–1.5 | 103 (25.75) | 87 (21.75) | 94 (23.50) | 19 (19.00) | ||

| 1.5–2 | 148 (37.00) | 128 (32.00) | 169 (42.25) | 40 (40.00) | ||

| above 2 | 111 (27.75) | 158 (39.50) | 108 (27.00) | 39 (39.00) | ||

| Domain | Infertility Treated Women | Control Group (N = 100) | Comparison between Groups p | p for Post Hoc Tests | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ART (N = 400) | IUI (N = 400) | IVF (N = 400) | Non-ART vs. Control | IUI vs. Control | IVF Control | Non-ART vs. IUI | Non-ART vs. IVF | IUI vs. IVF | |||

| Physical health, M ± SD | 56.6 ± 8.2 | 54.8 ± 8.3 | 54.9 ± 7.4 | 57.1 ± 9.3 | <0.001 | 0.636 | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.803 |

| Psychological, M ± SD | 66.6 ± 8.5 | 66.2 ± 8.5 | 66.1 ± 9.5 | 69.1 ± 9.2 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.517 | 0.425 | 0.881 |

| Social relationships, M ± SD | 71.7 ± 11.8 | 71.9 ± 12.2 | 70.3 ± 13.4 | 75.6 ± 13.0 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.832 | 0.109 | 0.070 |

| Environment, M ± SD | 69.8 ± 7.6 | 68.6 ± 8.6 | 68.5 ± 8.9 | 70.8 ± 8.8 | <0.001 | 0.293 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.047 | 0.038 | 0.927 |

| Domain | Infertility Treated Women | Comparison between Groups p | p for Post hoc Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ART (N = 400) | IUI (N = 400) | IVF (N = 400) | Non-ART vs. IUI | Non-ART vs. IVF | IUI vs. IVF | ||

| Total FertiQoL, M ± SD | 64.3 ± 12.1 | 65.2 ± 11.4 | 66.1 ± 12.7 | 0.109 | 0.272 | 0.035 | 0.315 |

| Core FertiQoL, M ± SD | 61.9 ± 14.1 | 62.8 ± 13.4 | 63.8 ± 14.5 | 0.152 | 0.385 | 0.053 | 0.282 |

| Emotional, M ± SD | 55.4 ± 18.9 | 53.8 ± 19.5 | 58.8 ± 17.8 | 0.001 | 0.212 | 0.010 | <0.001 |

| Mind/body, M ± SD | 59.9 ± 18.6 | 60.4 ± 17.6 | 62.5 ± 18.4 | 0.105 | 0.722 | 0.047 | 0.102 |

| Relational, M ± SD | 71.8 ± 17.3 | 74.8 ± 15.6 | 72.3 ± 16.6 | 0.022 | 0.009 | 0.617 | 0.035 |

| Social, M ± SD | 60.5 ± 17.1 | 62.1 ± 16.9 | 61.6 ± 16.6 | 0.398 | 0.187 | 0.350 | 0.701 |

| Treatment FertiQoL, M ± SD | 66.7 ± 12.8 | 67.7 ± 12.0 | 68.3 ± 13.0 | 0.163 | 0.249 | 0.059 | 0.460 |

| Environment, M ± SD | 66.5 ± 15.1 | 67.2 ± 14.1 | 68.0 ± 13.8 | 0.332 | 0.531 | 0.139 | 0.394 |

| Tolerability, M ± SD | 66.8 ± 18.0 | 68.2 ± 17.3 | 68.6 ± 17.3 | 0.289 | 0.252 | 0.131 | 0.715 |

| Covariate | IU or Category | Infertility Treated Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ART (N = 400) | IUI (N = 400) | IVF (N = 400) | |||||

| b | p | b | p | b | p | ||

| Age | years | 0.51 | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.074 | 0.37 | 0.020 |

| Place of residence | city | 0.46 | 0.585 | 2.43 | 0.002 | 2.34 | 0.009 |

| town | 1.26 | 0.171 | 0.60 | 0.508 | 0.55 | 0.561 | |

| rural area | reference | ||||||

| Level of education | basic vocational or secondary | 2.36 | 0.002 | 3.78 | <0.001 | 2.63 | 0.001 |

| tertiary | reference | ||||||

| BMI | kg/m2 | −0.33 | 0.036 | 0.18 | 0.139 | −0.29 | 0.071 |

| Having children | yes | 0.01 | 0.998 | 0.08 | 0.919 | −1.52 | 0.106 |

| no | reference | ||||||

| Time to get pregnant | years | −0.68 | 0.022 | −0.58 | 0.043 | −0.96 | 0.004 |

| Mode of employment | non-manual | reference | |||||

| manual or mixed | −0.08 | 0.923 | −0.86 | 0.266 | 0.39 | 0.630 | |

| Type of employment | constant | 1.51 | 0.031 | 1.24 | 0.056 | 1.64 | 0.023 |

| shift or not normalized | reference | ||||||

| Monthly net income per 1 person (thousand PLN), n (%) | below 1.5 | reference | |||||

| 1.5–2 | −0.27 | 0.761 | −1.33 | 0.129 | −1.26 | 0.175 | |

| above 2 | 0.06 | 0.942 | −0.20 | 0.804 | 0.57 | 0.494 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wdowiak, A.; Anusiewicz, A.; Bakalczuk, G.; Raczkiewicz, D.; Janczyk, P.; Makara-Studzińska, M. Assessment of Quality of Life in Infertility Treated Women in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084275

Wdowiak A, Anusiewicz A, Bakalczuk G, Raczkiewicz D, Janczyk P, Makara-Studzińska M. Assessment of Quality of Life in Infertility Treated Women in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084275

Chicago/Turabian StyleWdowiak, Artur, Agnieszka Anusiewicz, Grzegorz Bakalczuk, Dorota Raczkiewicz, Paula Janczyk, and Marta Makara-Studzińska. 2021. "Assessment of Quality of Life in Infertility Treated Women in Poland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084275

APA StyleWdowiak, A., Anusiewicz, A., Bakalczuk, G., Raczkiewicz, D., Janczyk, P., & Makara-Studzińska, M. (2021). Assessment of Quality of Life in Infertility Treated Women in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084275