Stakeholder Perspectives to Support Graphical User Interface Design for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

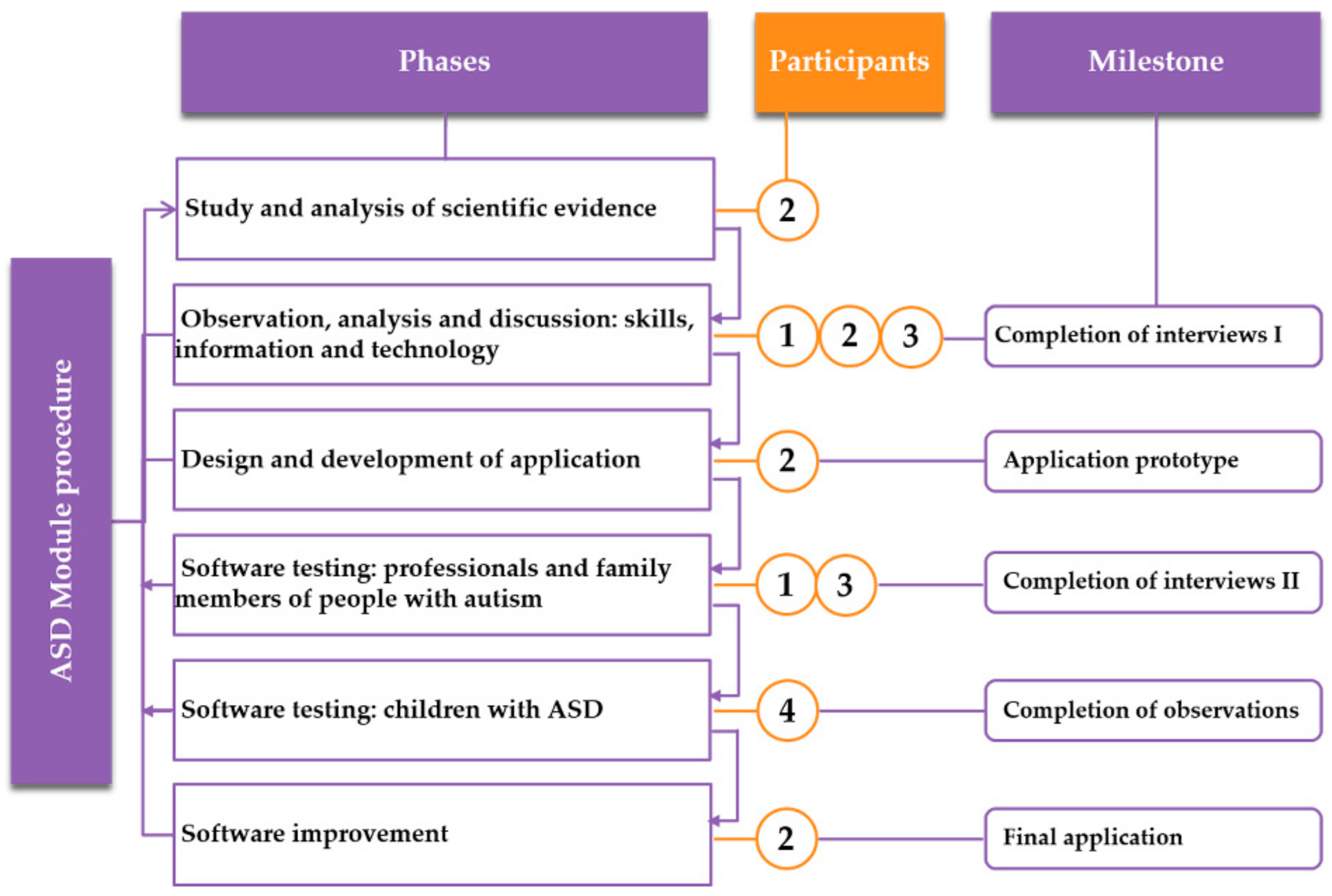

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Settings

- 1st Group: professionals with experience in the intervention with people with ASD.

- 2nd Group: professionals with experience in the development and design of technology for people with disability.

- 3rd Group: family members of people with ASD.

- 4th Group: children with ASD.

2.3. Procedure

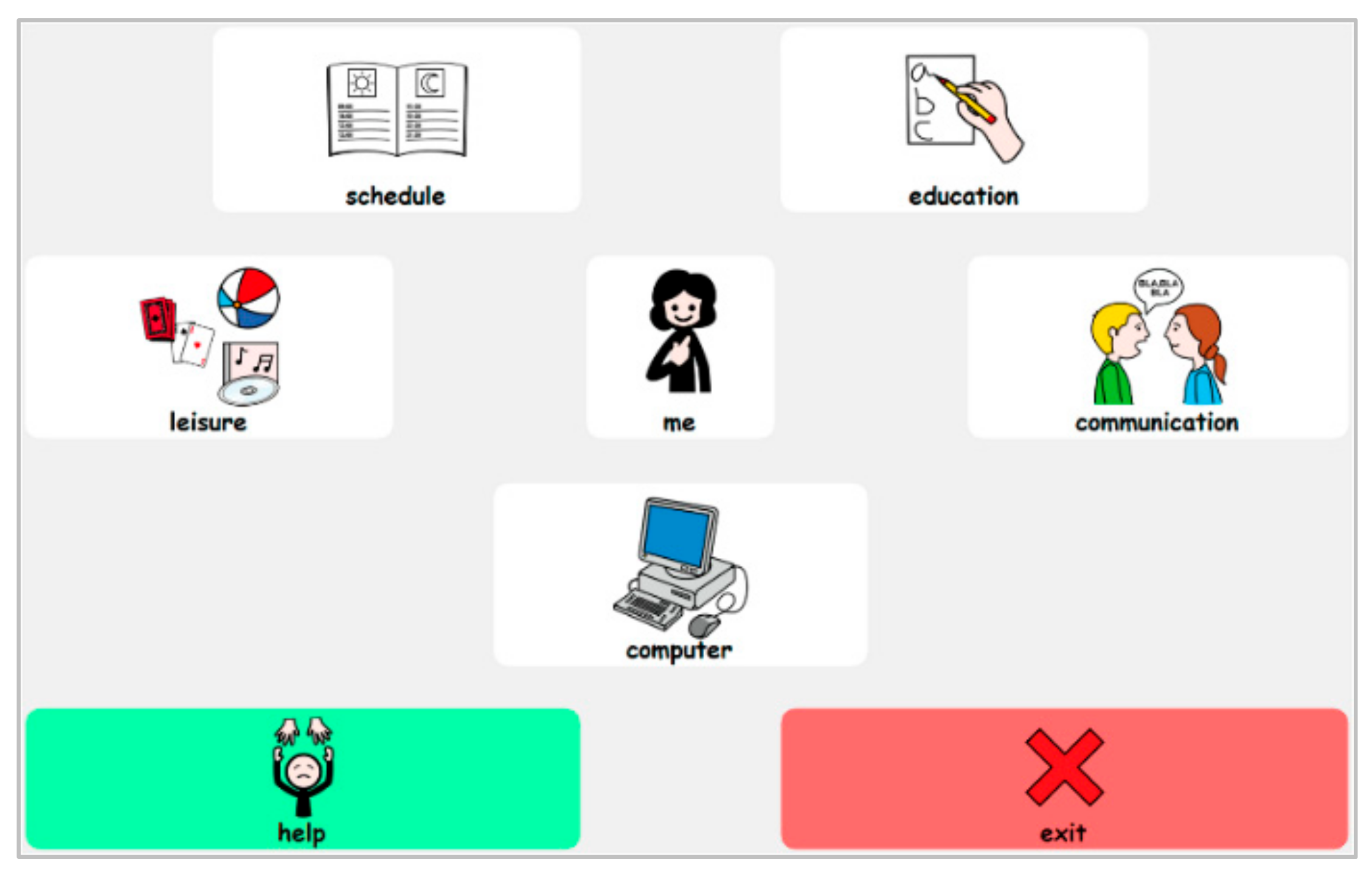

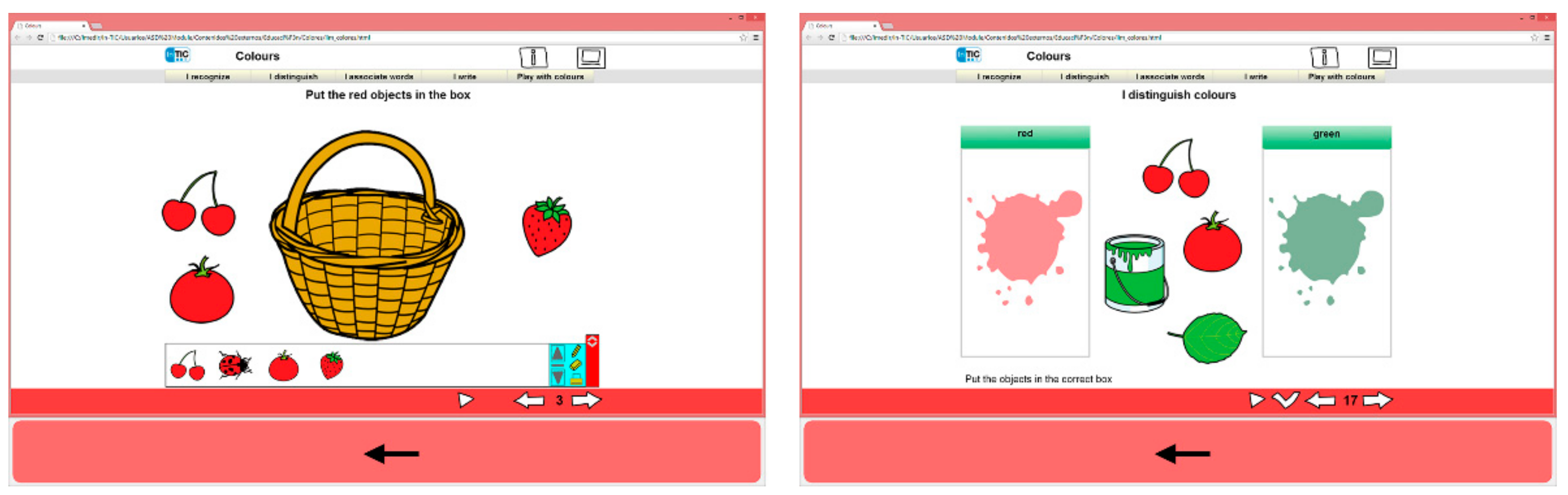

2.4. ASD Module: Software Tool

2.5. Information Collection Techniques

2.5.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.5.2. Observation and Usability Test

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results from Interviews

3.1.1. The User Has the Possibility to Customise All Relevant Aspects

“Considering that it is as a generic model, I would not add anything else. Only later, when you have the person you are going to work with, should you have to make several changes to focus on their preferences, their interests, and their person”(P17)

“I think that will be determined by the person who uses it. When it is used with the person, it will be the person who will determine. Well, I have to strengthen this part, or I have to eliminate, expand [the software options]... Once it is used, I think it will be the person who will determine the needs, the interests”(P18)

3.1.2. The Software and Its Contents Are Based on a Person’s Abilities, Needs and Interests

3.1.3. The Design of the Interface Is Simple, and the Information Displayed Is Simplified

“We, let us see, we are very interested in the structure. (…). The structure, including that of the program, that the environments speak for themselves, that the children can manage by themselves...”.(P6)

“Everything [should be] very clear and very intuitive at the moment, without much information; in the case of these children with more difficulties”.(P9)

“Logically, it cannot be one thing too much, with much information, because they will get lost... The more information you give on the screen, they will get lost, it is obvious. (…). So, little and straightforward”.

“Concrete information and always in four or five buttons. It means that there should not be too much saturation, a saturation of images”.(P25)

“This is a bit like writing and I always go from left to right”.(P8)

3.1.4. Use of Images to Display Information

“Because my son can take the belt out of the car and say to me: ‘Look, stop, stop... Where are we going?’. However, if he in the morning stands up, and takes a picture of his grandmother’s house, of a spa, of a walk along the beach, of a shopping basket, of a walk, of a coke…; any minimum indication (…); he already knows where he is going; that day, he already has it organized”.(P34)

“Let us see; life is a continuous change for someone who knows how to decode information. However, they (children with autism) do not have codes. They do not have the same code as us. In other words, if we do not move in the same code, I have to show them their code, what they know how to read and what they know how to internalize. What is it good for? They do not understand. What is it good for? Supports have to be very logical: visual keys in their daily life”.(P35)

“I think so because it is what I was telling you before, it is like very... visual. Everything that computers are, and all this. Moreover, they learn much better through the visual channel than through words, for example. You can tell them a huge story and they might understand it much better if you accompany it with pictures or just with images. So, computers give us this possibility”.(P23)

3.1.5. The Images Convey the Meaning of the Real Element

3.1.6. The Use of Images Allows Users to Adapt According to their Level of Visual Cognition

3.1.7. The Image Is Accompanied by the Written Word

3.1.8. Speech Synthesis Is Used to Facilitate Communication or as Reinforcement to the Command

“There are hypersensitivities. There are some who, perhaps, it may seem to them a very dry tone, very, very... metallic; perhaps. Yes... Very imperative, you know? Very ‘agenda’ (she imitates synthesised voice). Maybe if you modulate [the synthesised voice] a little more, no?”(P13)

“He [her son with autism] has oral language. But he can’t stand this kind of voice... He doesn’t like it. That brass tone, he can’t stand it. Because we had toys with that kind of voice and a kind of tablet but it repeated also in that singsong, and... he covered himself [pointing to the ears]”.(P35)

3.1.9. The Information Is Displayed in a Multimodal Way (Visual and Auditory) and Is Adapted According to the Sensory Style Preferred by Each Child

“I imagine it could be a further reinforcement. In addition to the visual, there is also the auditory. Why? It wouldn’t have to be incompatible. In fact, it’s the most natural thing, isn’t it? (…). It could be a customisable option. Take it away, when he already knew it”.(P2)

3.1.10. The Background Colour Is Used to Facilitate Information Processing

“Because as some of us use the Boardmaker, others, another; others, another; others, another... At one time, when we started, we thought we had to try in the centres of Galicia [for children with autism] to homogenise the use of a system because as the children went to camps or camps with one association or another, they could suddenly find themselves without language, right?”(P7)

“Let’s see, we would have to do it. I categorise. I’m talking about my classroom. Time and people’s names; that is, I have yellow backgrounds in everything that refers to people, and everything that refers to time is in blue. And then I work with white”.(P13)

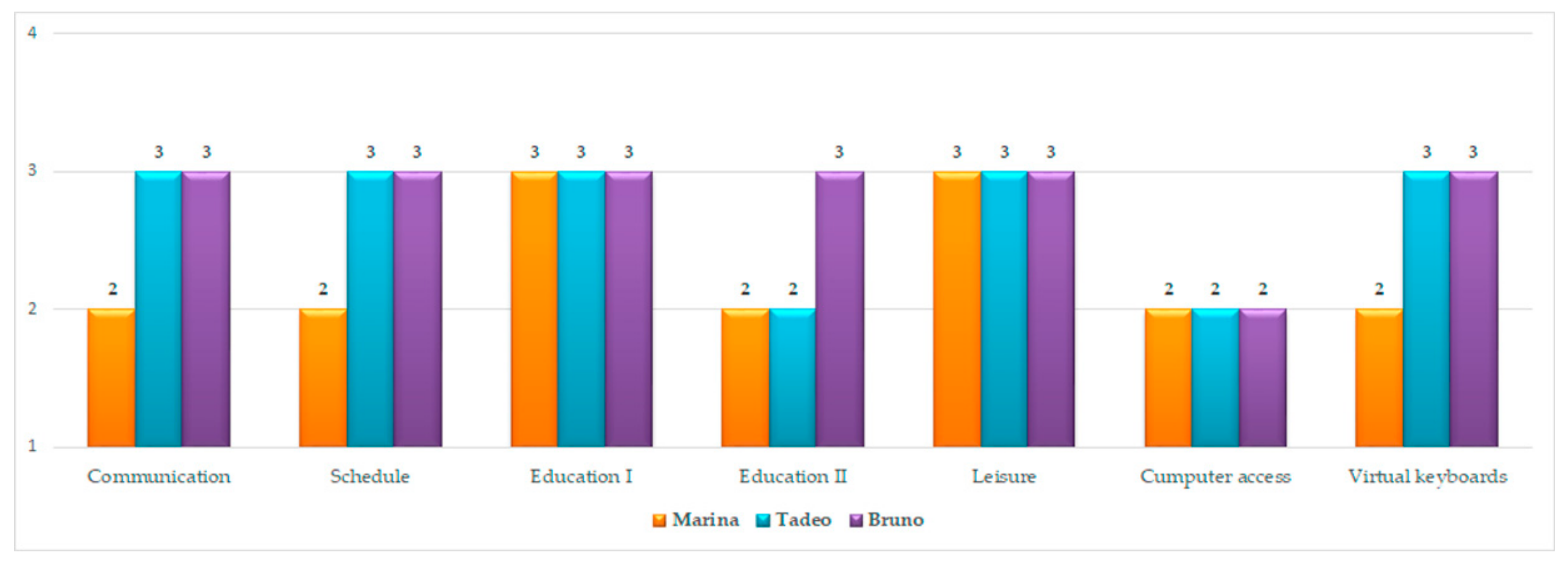

3.2. Results from Observation

- The children did not show behaviours of discomfort, rejection or opposition to the application or the tested interface.

- Marina, Tadeo and Bruno were involved in the task. In the exploration session, repetitive interactions with the software were observed, such as repetitive pressing of buttons or entering and exiting the different keyboards without apparent functionality.

- They showed technological competence to access and use the software and did not require physical support to operate the application.

- The need to personalise some images with photographs of the real environment of each child was detected (especially in the communication and schedule sections).

- The needs to reduce and customise the content options according to each child, their interests and needs, were detected.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A1. Semi-Structured Interview Guide I

- Based on your personal and/or professional experience, what is your opinion about the use of technology in the daily life of people with ASD?

- What options would you like the application to include based on appropriate options to facilitate the daily life of a child with autism? Can you give specific examples of these options?

- What characteristics should the program have? Can you give specific examples of these features?

Appendix A2. Semi-Structured Interview Guide II

- Demonstration and test of ASD Module

- What do you think about the contents of the ASD Module, in relation to the abilities and/or needs of children with ASD? Would you add or delete any of the contents?

- Which aspects or sections of the ASD Module would you highlight?

- How would you evaluate the ASD Module interface’s characteristics in terms of its usability for children with ASD (keyboard layout; button design and layout on the screen; use of colour in images, button background, and screen background; text: font type, size, location of the text concerning the image, among other characteristics; use and functionality of images; use and functionality of voice [synthesised or natural]; use, functionality, and modality of reinforcements)?

- What applicability do you think the ASD Module can have in the daily life of children with autism? Can you give specific examples?

- What contribution can the ASD Module make in comparison to the traditional methods used in the intervention with children with ASD?

- How would you define the ASD Module?

- What is your overall assessment of the ASD Module? What do you suggest as strengths and areas for improvement?

Appendix B

| Themes | Subthemes | Implications for ASD Module |

|---|---|---|

| The user has the possibility to customise all relevant aspects | Adaptation, personalisation, and customisation is essential It ′depends″ on the child Diversity across the spectrum Each child is unique | ASD Module as an example Customisation of all elements |

| The software and its contents are based on the person’s abilities, needs, and interests | Consider individual abilities, needs, interests, and motivation Tehnology for daily life Communication, leisure/play, time and activities management, and education are relevant for children with autism Interest and motivation as a key point Predilection for technology | ASM Module as digital support for daily life ASD Module’s contents: schedule, education, leisure, communication, and computer access Customisation of contents |

| The design of the interface is simple, and the information displayed is simplified | Differences in information processing Simplifying information Little information Information in large size Consistent distribution Left-right organisation | ASD Module keyboards configuration is simple (whole display area, grid pattern, left-right axis). Customisation |

| Use of images to display information | Ability to process visual information Visual supports as a ley element | ASD Module was based on the use of image |

| Images convey the meaning of the real element | Iconicity of images Realistic and representative symbols ARASAAC pictograms The transition from PCS to ARASAAC pictograms | ASD Module includes an extensive collection of ARASAAC pictograms |

| The use of images allows users to adapt according to their level of visual cognition | Adaptation to the level of visual cognition Concern about the generalised use of pictograms Possible hierarchy Need for evaluation | ASD Module allows users to cus-tomise the program using other symbol sets |

| The image is accompanied by the written word | Combination of visual and written information Written word Bottom of image Capital letters and serif type style Lowercase and linked typeface Customisation | The primary source of information is the combination of image and writ-ten word at the bottom of the image |

| Speech synthesis is used to facilitate communication or as reinforcement to the command | Use of synthesised voice AAC system Auditory reinforcement of information Simple information Auditory hyper-reactivity Customisation: digitised voice | ASD Module buttons include a voice command using speech synthesis Messages are simple, and specific They could be replaced by the digitised voice |

| The information is displayed in a multimodal way (visual and auditory) and is adapted ac-cording to the sensory style preferred by each child | Facilitate learning Multimodal way: visual and auditory stimuli Sensory preferences Customisation | Multimodal presentation for buttons is used to provide the information through the image, written word, and speech synthesis Possibility to delete or add infor-mation (preferred sensory style) |

| The background colour is used to facilitate the information processing | Colour as a facilitator of learning Classifications of PCS symbols Adaptation to the needs Colour contrast Soft colour tones Consistency | ASD Module use white as back-ground and tree main options for some actions (red, yellow, and green) Possibility of customisation |

References

- Fuentes, J.; Hervás, A.; Howlin, P. ESCAP practice guidance for autism: A summary of evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, DSM-5; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–996. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR. Surveill. Summ. 2020, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurie, M.H.; Warreyn, P.; Uriarte, B.V.; Boonen, C.; Fletcher-Watson, S. An International Survey of Parental Attitudes to Technology Use by Their Autistic Children at Home. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacMullin, J.A.; Lunsky, Y.; Weiss, J.A. Plugged in: Electronics use in youth and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, M.O.; Wenstrup, C. Television, Video Game and Social Media Use Among Children with ASD and Typically Developing Siblings. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 1258–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, S.H.; Odom, S.L.; Hume, K.; Sam, A. Technology use as a support tool by secondary students with autism. Autism 2018, 22, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colby, K.M.; Smith, D.C. Computers in the treatment of nonspeaking autistic children. Curr. Psychiatr. Ther. 1971, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colby, K.M. The rationale for computer-based treatment of language difficulties in nonspeaking autistic children. J. Autism Child. Schizophr. 1973, 3, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grynszpan, O.; Weiss, P.L.T.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Gal, E. Innovative technology-based interventions for autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Autism 2014, 18, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, J.R.; Stevenson, B.S.; Davis, L.L.; Geddes-Hall, J.; Test, D.W. Establishing Computer-Assisted Instruction to Teach Academics to Students with Autism as an Evidence-Based Practice. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, R.C. Computer-Assisted Instruction for Teaching Academic Skills to Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Literature. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2010, 25, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdoss, S.; Mulloy, A.; Lang, R.; O’Reilly, M.; Sigafoos, J.; Lancioni, G.; Didden, R.; El Zein, F. Use of computer-based interventions to improve literacy skills in students with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 1306–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdoss, S.; Lang, R.; Mulloy, A.; Franco, J.; O’Reilly, M.; Didden, R.; Lancioni, G. Use of Computer-Based Interventions to Teach Communication Skills to Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Behav. Educ. 2011, 20, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antão, J.; Oliveira, A.; Barbosa, R.; Crocetta, T.; Guarnieri, R.; Arab, C.; Masseti, T.; Antunes, T.; Silva, A.; Bezerra, I.; et al. Instruments for augmentative and alternative communication for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Clinics 2018, 73, e497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdoss, S.; Machalicek, W.; Rispoli, M.; Mulloy, A.; Lang, R.; O’Reilly, M. Computer-based interventions to improve social and emotional skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2012, 15, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berggren, S.; Fletcher-Watson, S.; Milenkovic, N.; Marschik, P.B.; Bölte, S.; Jonsson, U. Emotion recognition training in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of challenges related to generalizability. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2018, 21, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Brok, W.L.; Sterkenburg, P.S. Self-controlled technologies to support skill attainment in persons with an autism spectrum disorder and/or an intellectual disability: A systematic literature review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2015, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, K.; Steinbrenner, J.R.; Odom, S.L.; Morin, K.L.; Nowell, S.W.; Tomaszewski, B.; Szendrey, S.; McIntyre, N.S.; Yücesoy-Özkan, S.; Savage, M.N. Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism: Third Generation Review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSESA Technology Group. Definition of Technology for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders; CSESA Technology Group: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2013; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. CAOT Position Statement on Assistive Technology and Occupational Therapy; Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists: Otawa, ON, Canada, 2012; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zervogianni, V.; Fletcher-Watson, S.; Herrera, G.; Goodwin, M.; Pérez-Fuster, P.; Brosnan, M.; Grynszpan, O. A framework of evidence-based practice for digital support, co-developed with and for the autism community. Autism 2020, 24, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, K.; Rusu, C.; Quiñones, D.; Jamet, E. The Impact of Technology on People with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 2019, 19, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvat, L.; Kangas, A.J.; Szczech Moser, C. iPad Apps in Early Intervention and School-Based Practice. J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2014, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, C.M.; Travers, J.C. What’s App With That? Selecting Educational Apps for Young Children With Disabilities. Young Except. Child. 2013, 16, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Orange; IAutism. APPYautism. Available online: http://www.appyautism.com/ (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Boucenna, S.; Narzisi, A.; Tilmont, E.; Muratori, F.; Pioggia, G.; Cohen, D.; Chetouani, M. Interactive Technologies for Autistic Children: A Review. Cognit. Comput. 2014, 6, 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossard, C.; Grynspan, O.; Serret, S.; Jouen, A.-L.; Bailly, K.; Cohen, D. Serious games to teach social interactions and emotions to individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Comput. Educ. 2017, 113, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.; Pitt, I. Interaction Design: A Multidimensional Approach for Learners with Autism. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Interaction Design and Children - IDC ’06, Tampere, Finland, 7–9 June 2006; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.; Calvert, S. Brief Report: Vocabulary Acquisition for Children with Autism: Teacher or Computer Instruction. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000, 30, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, L.; Barry, M. Demystifying the Interface for Young Learners with Autism. In Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference Interfaces and Human Computer Interaction 2008, Amsterdan, The Netherlands, 22–27 July 2008; International Association for Development of the Information Society: Amsterdan, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 308–313. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.; Dautenhahn, K.; Powell, S.; Nehaniv, C. Guidelines for researchers and practitioners designing software and software trials for children with autism. J. Assist. Technol. 2010, 4, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, S.; Van der Paelt, S.; Ongenae, F.; De Backere, F.; De Turck, F. Empowering Children with ASD and Their Parents: Design of a Serious Game for Anxiety and Stress Reduction. Sensors 2020, 20, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.; Marques, A.; Queirós, C.; Orvalho, V. LIFEisGAME prototype: A Serious Game about Emotions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. PsychNol. J. 2013, 11, 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R.R.; Kirschbaum, C.R.; Picard, R.W. Broadening Accessibility Through Special Interests: A New Approach for Software Customization. In Proceedings of the 12th international ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility - ASSETS ’10, Orlando, FL, USA, 15–27 October 2010; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Grynszpan, O.; Martin, J.C.; Nadel, J. Multimedia interfaces for users with high functioning autism: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2008, 66, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, E.M.; Smyth, J.M.; Scherf, K.S. Designing Serious Game Interventions for Individuals with Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 3820–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porayska-Pomsta, K.; Frauenberger, C.; Pain, H.; Rajendran, G.; Smith, T.; Menzies, R.; Foster, M.E.; Alcorn, A.; Wass, S.; Bernadini, S.; et al. Developing technology for autism: An interdisciplinary approach. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2012, 16, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millen, L.; Edlin-White, R.; Cobb, S. The development of educational collaborative virtual environments for children with autism. In Proceedings of the The 5th Cambridge Workshop on Universal Access and Assistive Technology, Cambridge, UK, 22-25 March 2010; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, L.; Garzotto, F.; Gelsomini, M.; Oliveto, L.; Valoriani, M. Designing and Evaluating Touchless Playful Interaction for ASD Children. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Aarhus, Denmark, 17–20 June 2014; ACM: New York, USA, 2014; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Abirached, B.; Zhang, Y.; Park, J. Understanding User Needs for Serious Games for Teaching Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders Emotions. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications, Denver, CO, USA, 26–29 June 2012; AACE: Chesapeake, VA, USA, 2012; pp. 1054–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher-Watson, S.; Pain, H.; Hammond, S.; Humphry, A.; McConachie, H. Designing for young children with autism spectrum disorder: A case study of an iPad app. Int. J. Child-Computer Interact. 2016, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K.M.; Jagaroo, V. Contributions of Principles of Visual Cognitive Science to AAC System Display Design. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2004, 20, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanouni, P.; Jarus, T.; Zwicker, J.G.; Lucyshyn, J.; Fenn, B.; Stokley, E. Design Elements during Development of Videogame Programs for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Stakeholders’ Viewpoints. Games Health J. 2020, 9, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.S.Y.; Falkmer, M.; Chen, N.T.M.; Bӧlte, S.; Girdler, S. Designing a Serious Game for Youth with ASD: Perspectives from End-Users and Professionals. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 978–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.; Wilson, N.J.; Vaz, S.; Lee, H.; Cordier, R. Appropriateness of the TOBY Application, an iPad Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Thematic Approach. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 4053–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, A.; Johnson, H.; Smith, E.; Lengyel, D.; Brosnan, M. Designing computer-based rewards with and for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and/or Intellectual Disability. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 75, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenberger, C.; Good, J.; Alcorn, A.; Pain, H. Conversing through and about technologies: Design critique as an opportunity to engage children with autism and broaden research(er) perspectives. Int. J. Child-Computer Interact. 2013, 1, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boster, J.B.; McCarthy, J.W. Designing augmentative and alternative communication applications: The results of focus groups with speech-language pathologists and parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2018, 13, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnus, E. Everyday Occupations and the Process of Redefinition: A Study of How Meaning in Occupation Influences Redefinition of Identity in Women with a Disability. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2001, 8, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölte, S. The power of words: Is qualitative research as important as quantitative research in the study of autism? Autism 2014, 18, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Orange; Imedir. In-TIC: Integración de las Tecnologías de la Información y las Comunicaciones en los colectivos de personas con diversidad funcional [Integration of Information and Communication Technologies in the Groups of People with Functional Diversity]. Available online: http://www.proyectosfundacionorange.es/intic/ (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Macías, F. Libros Interactivos Multimedia [Interactive Multimedia Books]. Available online: https://www.educalim.com/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Gobierno de Aragón. Aragonese Center of Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Available online: https://arasaac.org/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process - Fourth Edition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7412410010p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2020 Sofware. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, T.R.; LeBlanc, L.A. Use of Technology in Interventions for Children with Autism. J. Early Intensive Behav. Interv. 2004, 1, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, C.; Chong, L. Software and Technologies Designed for People with Autism: What Do Users Want? In Proceedings of the 10th international ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility-Assets ’08, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–15 October 2008; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Roles and Responsibilities of Speech-Language Pathologists With Respect to Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Technical Report. ASHA Lead. 2004, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirenda, P.; Locke, P.A. A Comparison of Symbol Transparency in Nonspeaking Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. J. Speech Hear. Disord. 1989, 54, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, R.W.; Koul, R.K. Speech Output Technologies in Interventions for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Scoping Review. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2015, 31, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, K.M.; Madel, M. Eye Tracking Measures Reveal How Changes in the Design of Displays for Augmentative and Alternative Communication Influence Visual Search in Individuals With Down Syndrome or Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am. J. Speech-Language Pathol. 2019, 28, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Demographics | Professionals: ASD | Professionals: Technology | Family Members | Children with ASD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n [%]) | 20 (51.3) | 13 (33.3) | 3 (7.7) | 3 (7.7) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 41.6 (10.70) | 34.2 (11.72) | 57.0 (4.00) | 12.0 (1.00) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n [%]) | 17 (43.6) | 5 (12.8) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (5.1) |

| Male (n [%]) | 3 (7.7) | 8 (20.5) | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Expertise (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (8.50) | 4.9 (4.21) | NA | NA |

| 1. The user should have the possibility to customise all relevant aspects |

| 2. The software and its contents should be based on the person’s abilities, needs, and interests |

| 3. The design of the interface and the information displayed should be simplified |

| 4. Consider the use of images to display information |

| 5. The images should convey the meaning of the real element |

| 6. The images should allow personalisation according to users’ level of visual cognition. |

| 7. The image should be accompanied by the written word |

| 8. Speech synthesis is used to facilitate communication or as reinforcement to the command |

| 9. The information can be displayed in a multimodal way (visual and auditory) and will be adapted according to the sensory style preferred by each child |

| 10. The background colour should be used to facilitate the information processing |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Groba, B.; Nieto-Riveiro, L.; Canosa, N.; Concheiro-Moscoso, P.; Miranda-Duro, M.d.C.; Pereira, J. Stakeholder Perspectives to Support Graphical User Interface Design for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094631

Groba B, Nieto-Riveiro L, Canosa N, Concheiro-Moscoso P, Miranda-Duro MdC, Pereira J. Stakeholder Perspectives to Support Graphical User Interface Design for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094631

Chicago/Turabian StyleGroba, Betania, Laura Nieto-Riveiro, Nereida Canosa, Patricia Concheiro-Moscoso, María del Carmen Miranda-Duro, and Javier Pereira. 2021. "Stakeholder Perspectives to Support Graphical User Interface Design for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094631

APA StyleGroba, B., Nieto-Riveiro, L., Canosa, N., Concheiro-Moscoso, P., Miranda-Duro, M. d. C., & Pereira, J. (2021). Stakeholder Perspectives to Support Graphical User Interface Design for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094631