Elementary Schools’ Response to Student Wellness Needs during the COVID-19 Shutdown: A Qualitative Exploration Using the R = MC2 Readiness Heuristic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Coding and Analysis

3. Results

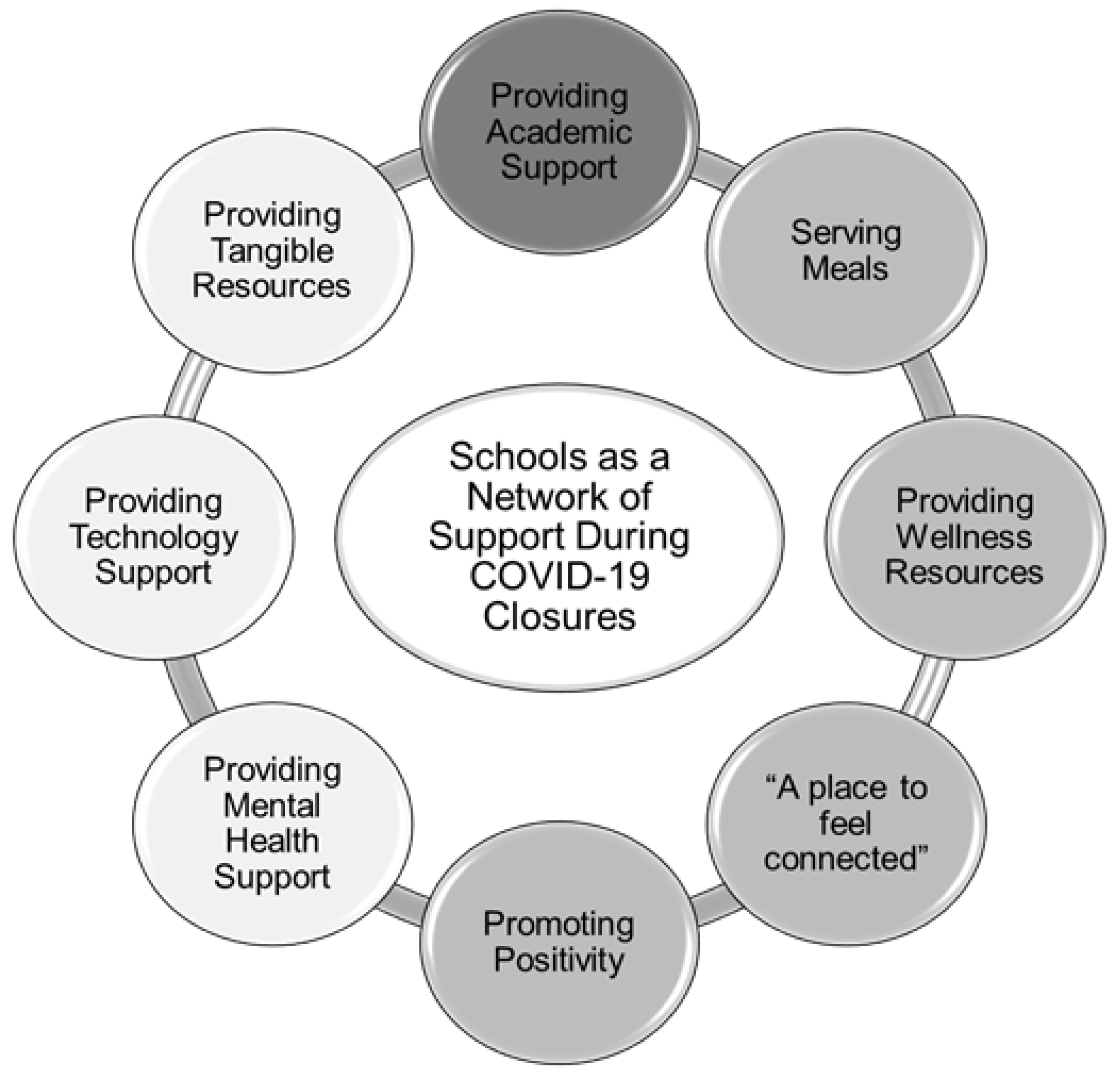

3.1. Innovation: A “Network of Support”

3.1.1. Serving Meals

3.1.2. Providing Wellness Resources

3.1.3. A Place to Feel Connected

3.1.4. Promoting Positivity

We met individually via Zoom with every staff member, [to tell] them what we appreciate about them. I’ve never seen more tears. People are really being reminded of why they do what they do and how gratifying a profession it is. And I got so many comments back like ‘This was so much better than getting a gift card to a restaurant’—Urban Principal

3.2. Readiness

3.2.1. Motivation

Simplicity and Compatibility

Priority

Observability

3.2.2. Capacity (General)

Process Capacities

Schools are general very reticent to change, but [we] really had to adapt quickly…If something didn’t work, we brainstormed that day, and tried something new the next day. We were not prepared at all, [but we] became prepared. When it’s all over, I think we’ll look back and go, ‘wow, we can pat ourselves on the back.’ There’s a lot to be proud of.—Urban Principal

Resource Utilization

Staff Capacities

People always take very seriously the academic part of our mission, but I’m not sure that staff are so focused on how kids are feeling, what they’re going through, what their home life looks like. That gets compartmentalized, so the school nurse, the school counselor, or school psychologist, they worry about those things, and everybody else does their job. In this situation, we’ve gotten a much broader view of our jobs. Our [Spanish and art] teachers have gotten much more involved in finding out what’s happening with kids at home.—Urban Principal

Internal Operations

Leadership

3.2.3. Capacity (Innovation-Specific)

Knowledge and Skills

We’re very fortunate…that we have a technology director who also has a staff of technology integrationists, and every elementary building has a media specialist. All of those people have expertise in distance learning, and were able to problem solve 99 percent of the problems that we’ve run into.

Program Champion

Supportive Climate

Inter-Organizational Relationships

3.3. Differences between Rural/Urban Schools

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. National School Lunch Program. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/child-nutrition-programs/national-school-lunch-program.aspx (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School Decision-Making Tool for Parents, Caregivers, and Guardians. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/decision-tool.html (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- The Coronavirus Spring: The Historic Closing of U.S. Schools (A Timeline). Available online: https://www.edweek.org/leadership/the-coronavirus-spring-the-historic-closing-of-u-s-schools-a-timeline/2020/07 (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Von Hippel, P.T.; Workman, J. From Kindergarten Through Second Grade, U.S. Children’s Obesity Prevalence Grows Only During Summer Vacations. Obesity 2016, 24, 2296–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Story, M.; Nanney, M.S.; Schwartz, M.B. Schools and Obesity Prevention: Creating School Environments and Policies to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. Milbank Q. 2009, 87, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.P.; Johnston, C.A.; Chen, T.-A.; O’Connor, T.A.; Hughes, S.O.; Baranowski, J.; Woehler, D.; Baranowski, T. Seasonal Variability in Weight Change during Elementary School. Obesity 2015, 23, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nord, M.; Romig, K. Hunger in the Summer. J. Child. Poverty 2006, 12, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.G.; Armstrong, B.; Hunt, E.; Beets, M.W.; Brazendale, K.; Dugger, R.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Pate, R.R.; Maydeu-Olivares, A.; Saelens, B.; et al. The Impact of Summer Vacation on Children’s Obesogenic Behaviors and Body Mass Index: A Natural Experiment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewallen, T.C.; Hunt, H.; Potts-Datema, W.; Zaza, S.; Giles, W. The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model: A New Approach for Improving Educational Attainment and Healthy Development for Students. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Results from the School Health Policies and Practices Study 2014. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/shpps/pdf/shpps-508-final_101315.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Michael, S.L.; Merlo, C.L.; Basch, C.E.; Wentzel, K.R.; Wechsler, H. Critical Connections: Health and Academics. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 740–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwartz, A.E.; Rothbart, M.W. Let them eat lunch: The impact of universal free meals on student performance. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2020, 39, 376–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.; Saliasi, E.; van den Berg, V.; Uijtdewilligen, L.; de Groot, R.H.M.; Jolles, J.; Andersen, L.B.; Bailey, R.; Chang, Y.-K.; Diamond, A.; et al. Effects of Physical Activity Interventions on Cognitive and Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents: A Novel Combination of a Systematic Review and Recommendations from an Expert Panel. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chriqui, J.F.; Leider, J.; Temkin, D.; Piekarz-Porter, E.; Schermbeck, R.M.; Stuart-Cassel, V. State Laws Matter When It Comes to District Policymaking Relative to the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Framework. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edge Research. Healthy Schools Research—Phase II. Available online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/09/healthy-schools-research-phase---ii.html (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Schuler, B.R.; Saksvig, B.I.; Nduka, J.; Beckerman, S.; Jaspers, L.; Black, M.M.; Hager, E.R. Barriers and Enablers to the Implementation of School Wellness Policies: An Economic Perspective. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 19, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, M.M.; Blaabæk, E.H. Inequality in Learning Opportunities during Covid-19: Evidence from Library Takeout. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2020, 68, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masonbrink, A.R.; Hurley, E. Advocating for Children During the COVID-19 School Closures. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20201440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, E.; Jack, R.; Halloran, C.; Schoof, J.; McLeod, D.; Yang, H.; Roche, J.; Roche, D. Disparities in Learning Mode Access Among K–12 Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic, by Race/Ethnicity, Geography, and Grade Level—United States, September 2020–April 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Widmar, N.O. Revisiting the Digital Divide in the COVID-19 Era. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drzensky, F.; Egold, N.; van Dick, R. Ready for a Change? A Longitudinal Study of Antecedents, Consequences and Contingencies of Readiness for Change. J. Chang. Manag. 2012, 12, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hall, G.E.; Hord, S.M. Implementing Change: Patterns, Principles, and Potholes; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oterkiil, C.; Ertesvåg, S.K. Schools’ Readiness and Capacity to Improve Matter. Educ. Inq. 2012, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J. A Theory of Organizational Readiness for Change. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scaccia, J.P.; Cook, B.S.; Lamont, A.; Wandersman, A.; Castellow, J.; Katz, J.; Beidas, R.S. A Practical Implementation Science Heuristic for Organizational Readiness: R = MC2. J. Commun. Psychol. 2015, 43, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/qualitative-data-analysis/book246128 (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Saldana, J.; Omasta, M. Qualitative Research: Analyzing Life; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.; Crabtree, B.F.; Damschroder, L.; Hamilton, A.B.; Heurtin-Roberts, S.; Leeman, J.; Padgett, D.K.; Palinkas, L.; Rabin, B.; Reisinger, H.S. Qualitative Methods In Implementation Science; National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, n.d.

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Readiness Building Systems; Wandersman, A.; Scaccia, J.P. Readiness Briefing Paper FY 2017–2018; The Wandersman Center: Columbia, SC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, K.; Babbin, M.; McKee, S.; McGinn, K.; Cohen, J.; Chafouleas, S.; Schwartz, M. Dedication, Innovation, and Collaboration: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of School Meals in Connecticut during COVID-19. J. Agric. Food Syst. Commun. Dev. 2021, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.; Wiggers, J.; Wyse, R.; Williams, C.M.; Sutherland, R.; Yoong, S.L.; Lecathelinais, C.; Wolfenden, L. Factors Associated with the Implementation of a Vegetable and Fruit Program in a Population of Australian Elementary Schools. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, K.G.; Lawton, R.; Hugh-Jones, S. Factors Affecting the Implementation of a Whole School Mindfulness Program: A Qualitative Study Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lau, E.Y.; Wandersman, A.H.; Pate, R.R. Factors Influencing Implementation of Youth Physical Activity Interventions: An Expert Perspective. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sports Med. 2016, 1, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jowell, A.H.; Bruce, J.S.; Escobar, G.V.; Ordonez, V.M.; Hecht, C.A.; Patel, A.I. Mitigating Childhood Food Insecurity during COVID-19: A Qualitative Study of How School Districts in California’s San Joaquin Valley Responded to Growing Needs. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.B.; Carson, R.L.; Webster, C.A.; Singletary, C.R.; Castelli, D.M.; Pate, R.R.; Beets, M.W.; Beighle, A. The Application of an Implementation Science Framework to Comprehensive School Physical Activity Programs: Be a Champion! Front. Public Health 2018, 5, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carlson, J.A.; Engelberg, J.K.; Cain, K.L.; Conway, T.L.; Geremia, C.; Bonilla, E.; Kerner, J.; Sallis, J.F. Contextual Factors Related to Implementation of Classroom Physical Activity Breaks. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McLoughlin, G.M.; Candal, P.; Vazou, S.; Lee, J.A.; Dzewaltowski, D.A.; Rosenkranz, R.R.; Lanningham-Foster, L.; Gentile, D.A.; Liechty, L.; Chen, S. Evaluating the Implementation of the SWITCH® School Wellness Intervention and Capacity-Building Process through Multiple Methods. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindle, T.; Johnson, S.L.; Davenport, K.; Whiteside-Mansell, L.; Thirunavukarasu, T.; Sadasavin, G.; Curran, G.M. A Mixed-Methods Exploration of Barriers and Facilitators to Evidence-Based Practices for Obesity Prevention in Head Start. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, Y.; Mitric, S.; Chriqui, J.F. Addressing Equity in Rural Schools: Opportunities and Challenges for School Meal Standards Implementation. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes-Maslow, L.; Osborne, I.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B. Best Practices and Innovative Solutions to Overcome Barriers to Delivering Policy, Systems and Environmental Changes in Rural Communities. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pattison, K.L.; Hoke, A.M.; Schaefer, E.W.; Alter, J.; Sekhar, D.L. National Survey of School Employees: COVID-19, School Reopening, and Student Wellness. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.Y.; Wang, C.; Espelage, D.L.; Fenning, P.; Jimerson, S.R. COVID-19 and School Psychology: Adaptations and New Directions for the Field. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 49, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Dinh, J.; Lane, H.; McGuirt, J.; Zafari, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gutermuth, L.; Hager, E.R.; Sessoms-Park, L.; Cooper, C.; et al. Evaluation of COVID-19 School Meals Response: Spring 2020. 2020. Available online: http://www.marylandschoolwellness.org/media/SOM/Departments/Pediatrics/Maryland-School-Wellness/Documents/School-Meal-Evaluation-Report_01_07_21_FINAL-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Winthrop, R.; Vegas, E. Beyond Reopening Schools: How Education Can Emerge Stronger than before COVID-19; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/beyond-reopening-schools-how-education-can-emerge-stronger-than-before-covid-19/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Kinsey, E.W.; Hecht, A.A.; Dunn, C.G.; Levi, R.; Read, M.A.; Smith, C.; Niesen, P.; Seligman, H.K.; Hager, E.R. School Closures During COVID-19: Opportunities for Innovation in Meal Service. Am. J. Public. Health 2020, 110, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity; Baciu, A., Negussie, Y., Geller, A., Weinstein, J.N., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.; Arkin, E.; Orleans, T.; Proctor, D.; Plough, A. What Is Health Equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Defining Readiness. Available online: https://www.wandersmancenter.org/defining-readiness.html (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Walker, T.J.; Brandt, H.M.; Wandersman, A.; Scaccia, J.; Lamont, A.; Workman, L.; Dias, E.; Diamond, P.M.; Craig, D.W.; Fernandez, M.E. Development of a Comprehensive Measure of Organizational Readiness (Motivation × Capacity) for Implementation: A Study Protocol. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2020, 1, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin, G.M.; McCarthy, J.A.; McGuirt, J.T.; Singleton, C.R.; Dunn, C.G.; Gadhoke, P. Addressing Food Insecurity through a Health Equity Lens: A Case Study of Large Urban School Districts during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Urban Health 2020, 97, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| School Characteristics (n = 39) | ||

| Student race/ethnicity | ||

| ≥50% Asian | 1 | 2.6 |

| ≥50% Black | 3 | 7.7 |

| ≥50% Hispanic | 5 | 12.8 |

| ≥50% White | 19 | 48.7 |

| Other | 11 | 28.2 |

| Socioeconomic status (% of students eligible for free/reduced-priced meals) | ||

| Higher (<33%) | 8 | 20.5 |

| Middle (≥33% to <66%) | 16 | 41.0 |

| Lower (≥66%) | 12 | 30.8 |

| Not reported | 3 | 7.7 |

| School locale | ||

| City: Large | 6 | 15.4 |

| City: Mid-size | 4 | 10.3 |

| City: Small | 9 | 23.1 |

| Rural: Fringe | 9 | 23.1 |

| Rural: Distant | 9 | 23.1 |

| Rural: Remote | 2 | 5.0 |

| School size (number of students enrolled) | ||

| >650 | 9 | 23.1 |

| 450 to 649 | 9 | 23.1 |

| 250 to 449 | 12 | 30.7 |

| <249 | 9 | 23.1 |

| Region | ||

| West | 8 | 20.5 |

| Midwest | 10 | 25.7 |

| South | 13 | 33.3 |

| Northeast | 8 | 20.5 |

| Interview Participant Characteristics (n = 50) | ||

| Role at School | ||

| Administrator (Principal/Assistant Principal/Head of School) | 20 | 40.0 |

| Physical Education Teacher | 9 | 18.0 |

| Classroom Teacher | 2 | 4.0 |

| Counselor | 3 | 6.0 |

| Nurse | 2 | 4.0 |

| Administrative Assistant/Office Manager | 7 | 14.0 |

| Other | 7 | 14.0 |

| Gender (self-reported) | ||

| Female | 40 | 80.0 |

| Male | 10 | 20.0 |

| R = MC2 Construct and Definition | Theme(s) |

|---|---|

| Motivation/Momentum | |

| Simplicity and Compatibility. Extent to which network was perceived as an easy role for schools to fill or within the way school usually does things | Theme 1: Schools are often the hub of communities/strategic distribution points for resources Theme 2: Pre-existing services were not difficult to adapt or maintain for COVID-19 delivery |

| Priority. Importance of network of support compared to academics | Theme 1: State mandates required schools to provide meals to students Theme 2: School personnel went above and beyond to extend meal services to the whole community out of a desire to meet basic needs |

| Observability. Ability to see or foresee that providing a network of support was what families needed during COVID | Theme 1: Student participation rates in existing programs such as free/reduced price meals made the need for a network of support clear Theme 2: Personnel from smaller schools described greater ease in identifying which families had the greatest need |

| Ability to Pilot. Degree to which network can be tested or experimented with | Few excerpts emerged; no themes were identified |

| General Capacity | |

| Process Capacities. Ability to plan, implement and evaluate efforts to meet student needs | Theme 1: There was little preparedness for the network of support, and there was a lot of trial and error Theme 2: Facilitating factors included: existing technological systems; adequate staff, existing programs or preparedness plans; teamwork; learning from other districts; hands-on leadership; knowing students’ needs; having spring break week to prepare Theme 3: Barriers included: lack of systems and technology access; constant decision changes/slow decision making by state/local leaders, COVID-19 safety concerns; uncertainty Theme 4: Schools used many informal methods to monitor/adjust the network to better meet student needs, including extensive communication with parents Theme 5: Schools used many informal methods to monitor/adjust the network to improve operations or logistics and reduce virus spread |

| Resource Utilization. Ability to use existing funds or technological resources to create infrastructure for student wellness | Theme 1: Technology was the most critical resource for supporting students during COVID-19; distribution of laptops and/or hotspots was a high priority Theme 2: Some technology barriers could not be overcome, and schools instead delivered hardcover textbooks, flash drives or paper packets via bus. Theme 3: Having learning management systems (e.g., Google Classroom, Class Dojo) and more tech-trained staff were advantages |

| Staff Capacities. Having enough staff who were able to take on any role to meet student needs | Theme 1: Many staff members took on new roles to keep operations going, minimize number of staff in the building, and remain employed Theme 2: Staff primarily pivoted to helping with meal service Theme 3: Some staff described new roles: calling students who were not attending class; bilingual staff aiding non-English-speaking parents; connecting students to community resources; providing technical support |

| Internal Operations. Effectiveness of communication networks and teamwork among staff | Theme 1: School closures necessitated new methods of communication among staff Theme 2: Teamwork and resource-sharing were essential and occurred naturally; staff members teamed up in new ways to achieve their goals Theme 3: Caregivers served a key new role in operating the network; communication with families was essential, but challenging |

| Leadership. Effectiveness of school and district leaders | Theme 1: Local leadership was perceived very positively, views of non-local leadership (state/federal) were mixed Theme 2: Positive leadership actions often overlapped with themes related to internal operations and process capacities, including: (1) being attentive and in frequent contact, sharing decision making without creating “decision fatigue” among staff; (2) providing emotional support for staff and students, including “trusting” teachers and keeping expectations realistic Theme 3: Leadership were influential in ensuring students had the supplies and resources they needed |

| Innovation-Specific Capacity | |

| Knowledge and Skills. Ability of staff to create network of support for students | Theme 1: Staff had base knowledge, but still experienced a learning curve Theme 2: As noted in internal operations, parents become key parts of organization who also needed knowledge and skills to facilitate student success; lack of parent knowledge was a barrier |

| Program Champion. Specific people within the school who are particularly promotive of network | Theme 1: While teamwork was often noted, sometimes individuals who excelled in filling new/existing roles were mentioned as leaders |

| Supportive Climate. Staff attitudes, parent attitudes, and examples of culture, norms or values that facilitate network | Theme 1: Staff were willing to do “whatever it takes” to support families, many spoke that taking care of each other was part of the school culture Theme 2: Meeting basic needs was a primary concern of school staff, rather than over-emphasizing academics |

| Inter-organizational Relationships. Support for network from other schools, community partners, volunteers, other external organizations | Theme 1: Most schools relied on local food banks, churches, state agencies, internet companies, and other organizations to help meet student needs Theme 2: Teachers and administrators worked across districts to collaborate and share resources Theme 3: Teachers utilized online networks to adapt their instruction and transition to virtual platforms |

| Intra-organizational Relationships. Relationships between administrators, staff and families to support network | Intra-organizational relationships had extensive overlap with process capacities/internal operations; few unique excerpts emerged; no additional themes were identified |

| Theme(s) | Representative Quote(s) |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Being a “small” school or in a small district was often viewed by rural personnel to be advantageous during the COVID-19 response. Being small meant having (1) fewer technology and food resources to distribute; (2) more knowledge of individual student/family situations and needs; and (3) a more tightknit staff and communication network. Rural personnel also described the importance of their role as a “hub” of the community. | “Luckily we’re a smaller school, smaller staff. We all work well together anyways. So I think that was a positive for us.”—Rural Physical Education Teacher “We’re kind of a small, small community. So most people just go straight to the boss and they ask the questions and they get the answers they need.”—Rural Principal “Every student received at least a Chromebook if not an iPad, or both, and um laptops for the older kids. So everyone got something…So because we’re so small, I think it was a little bit easier for us to take this on… we’re mighty because we’re small.”—Rural Principal |

| Theme 2: Both urban and rural schools faced technology-related barriers, but rural personnel described unique barriers (e.g., children lived in more remote areas where the distribution of hotspots was not possible). Rural personnel described innovative mitigation strategies, but noted that for some families, the digital divide could not be overcome and they could not be integrated into the network of support. | “I only have one student that’s getting online with me and my team teachers only have 4 students out of our 27. So we’re copying out lesson plans that we’re making. And they’re being placed at the little grocery store that’s in the nearby town, and parents are asked to go to that grocery store and pick up the lesson plans for their students.”—Rural Classroom Teacher “We do have some resources that we put out on Facebook and the web page for activity ideas and things like that to go along with their lessons, but we’re very rural, and we’re very spread out. So we have a lot of students who don’t have access to internet actually.”—Rural Secretary |

| Theme 3: Rural schools depended on a larger network of community partnerships and support (including faith-based and other community organizations and parent volunteers) to meet the needs of students/families, while urban school participants were more likely to describe how school staff came together to meet the needs of students/families. | “One of my volunteers that attends the local Christian church stepped up, talked with her minister, and we did some of the packing of the bags in the church basement. So this has been a blessing…we have excellent community, and they are such caring people.”—Rural School Nurse |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calvert, H.G.; Lane, H.G.; McQuilkin, M.; Wenner, J.A.; Turner, L. Elementary Schools’ Response to Student Wellness Needs during the COVID-19 Shutdown: A Qualitative Exploration Using the R = MC2 Readiness Heuristic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010279

Calvert HG, Lane HG, McQuilkin M, Wenner JA, Turner L. Elementary Schools’ Response to Student Wellness Needs during the COVID-19 Shutdown: A Qualitative Exploration Using the R = MC2 Readiness Heuristic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010279

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalvert, Hannah G., Hannah G. Lane, Michaela McQuilkin, Julianne A. Wenner, and Lindsey Turner. 2022. "Elementary Schools’ Response to Student Wellness Needs during the COVID-19 Shutdown: A Qualitative Exploration Using the R = MC2 Readiness Heuristic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010279

APA StyleCalvert, H. G., Lane, H. G., McQuilkin, M., Wenner, J. A., & Turner, L. (2022). Elementary Schools’ Response to Student Wellness Needs during the COVID-19 Shutdown: A Qualitative Exploration Using the R = MC2 Readiness Heuristic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010279