Benefits, Satisfaction and Limitations Derived from the Performance of Intergenerational Virtual Activities: Data from a General Population Spanish Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Analysis

3.2. Benefits of Performing Intergenerational Virtual Activities

3.3. Satisfaction of Performing Intergenerational Virtual Activities

3.4. Limitations of People Who Perform Intergenerational Virtual Activities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H. GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1160–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report Geneva; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.A.; Saklofske, D.H. The relationship between trait emotional intelligence, resiliency, and mental health in older adults: The mediating role of savouring. Aging Ment. Health. 2018, 22, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaja, S.J.; Moxley, J.H.; Rogers, W.A. Social Support, Isolation, Loneliness, and Health among Older Adults in the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 728658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R.; Nellums, L.B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020, 5, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, B. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Global Health Res. Policy. 2020, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickus, M.A.; Luz, C.C. Televisits: Sustaining long distance family relationships among institutionalized elders through technology. Aging Ment. Health 2002, 6, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Older Adults and Technology Use; PEW Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, H.R.; Kroll, M.; Fink, D.; de Rosario, H.; Gschwind, Y.J. Technology use, adoption and behavior in older adults: Results from the iStoppFalls project. Educ. Gerontol. 2016, 42, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marston, H.R.; Samuels, J. A review of age friendly virtual assistive technologies and their effect on daily living for careers and dependent adults. Healthcare 2019, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Celdrán, M.; Serrat, R.; Villar, F.; Montserrat, R. Exploring the Benefits of Proactive Participation among Adults and Older People by Writing Blogs. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, M.; Ingen, E.J.V.; de Boer, A.; Slootman, M.W. ICT als instrument voor het sociaal en emotioneel welbevinden [ICT as an instrument for social and emotional ageing. A qualitative study with older adults with cognitive impairments]. Tijdschr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, J.; Durán-Sánchez, A.; Del Río-Rama, M.C.; Correa-Quezada, R. Older Adults and Digital Society: Scientific Coverage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, W. Internet use, online communication, and ties in Americans’ networks. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2013, 31, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissitsa, S.; Chachashvili-Bolotin, S. Life satisfaction in the internet age—Changes in the past decade. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.; Betts, L.R.; Gardner, S.E. Older adults’ experiences and perceptions of digital technology: (Dis)empowerrment, wellbeing, and inclusion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, L.I.; Wahl, H.W. Predictors of performance in everyday technology tasks in older adults with and without mild cognitive impairment. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martin, J.; García, J.N. Patterns of Web 2.0 tool use among young Spanish people. Comput Educ. 2013, 67, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Prieto, C.; García-Sánchez, J.N.; Canedo-García, A. Impact of Life Experiences and Use of Web 2.0 Tools in Adults and Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, B. Case study: WhatsApp support through the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs. Resid. Care 2020, 22, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, A.M.; Cotton, S.R. COVID-19’s Influence on Information and Communication Technologies in Long-Term Care: Results from an Online Survey with Long-Term Care Administrators. JMIR Aging. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canedo-García, A.; García-Sánchez, J.N.; Pacheco-Sanz, D.I. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Intergenerational Programs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canedo-García, A.; García-Sánchez, J.N.; Pacheco-Sanz, D.I. Acción conjunta intergeneracional (ACIG). Descripción de variables intervinientes. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychology. Rev. Infad Psicol. 2019, 3, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallcook, S.; Nygård, L.; Kottorp, A.; Malinowsky, C. The use of everyday information communication technologies in the lives of older adults living with and without dementia in Sweden. Assist Technol. 2019, 33, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Encuesta Sobre Equipamiento y uso de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en los Hogares 2015 (TIC-H’15). Available online: https://www.ine.es/metodologia/t25/t25304506615.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Chen, Y.R.; Schulz, P.J. The effect of information and communication technology interventions on reducing social isolation in the elderly: A systematic review. J. Med. Int. Res. 2016, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köttl, H.; Cohn-Schwartz, E.; Ayalon, L. Self-Perceptions of Aging and Everyday ICT Engagement: A Test of Reciprocal Associations. J. Gerontol. B 2021, 76, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, S.; Marston, H.R.; Olynick, J.; Musselwhite, C.; Kulczycki, C.; Genoe, R.; Xiong, B. Intergenerational Effects on the Impacts of Technology Use in Later Life: Insights from an International, Multi-Site Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasunaga, M.; Murayama, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Ohba, H.; Suzuki, H.; Nonaka, K.; Kuraoka, M.; Sakurai, R.; Nishi, M.; Sakuma, N.; et al. Multiple impacts of an intergenerational program in Japan: Evidence from the Research on Productivity through Intergenerational Sympathy Project. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16 (Suppl. 1), 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnes, D.; Sheppard, C.; Henderson, C.R., Jr.; Wassel, M.; Cope, R.; Barber, C.; Pillemer, K. Interventions to Reduce Ageism Against Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2019, 109, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, S. Intergenerational Connections in Digital Families; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chonody, J.; Wang, D. Connecting Older Adults to the Community through Multimedia: An Intergenerational Reminiscence Program. Activ. Adapt. Aging. 2013, 37, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamliel, T.; Gabay, N. Knowledge exchange, social interactions, and empowerment in an intergenerational technology program at school. Educ. Gerontol. 2014, 40, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoBuono, D.L.; Leedahl, S.N.; Maiocco, E. Older adults learning technology in an in-tergenerational program: Qualitative analysis of areas of technology requested for assistance. Gerontechnology 2019, 18, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leedahl, S.N.; Brasher, M.S.; Estus, E.; Breck, B.M.; Dennis, C.B.; Clark, S.C. Implementing an interdisciplinary intergenerational program using the Cyber Seniors® reverse mentoring model within higher education. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2019, 40, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

(A). Using (1)/(2)/(3)/(4) with people of another generation produces BENEFITS for your: Physical health, Mental health, Mood, -Relationships, Self-determination, Social participation, Economic well-being, Professional well-being, Academic education.

|

(B). With WHO and FREQUENCY do you use (1)/(2)/(3)/(4)? Partner, Child, Grandchild, Parent, Grandparent, Sibling, Other relative, Friend, Neighbor, Colleague, Person in the same situation, Professional of an institution, Professional of health, social or academic services.

|

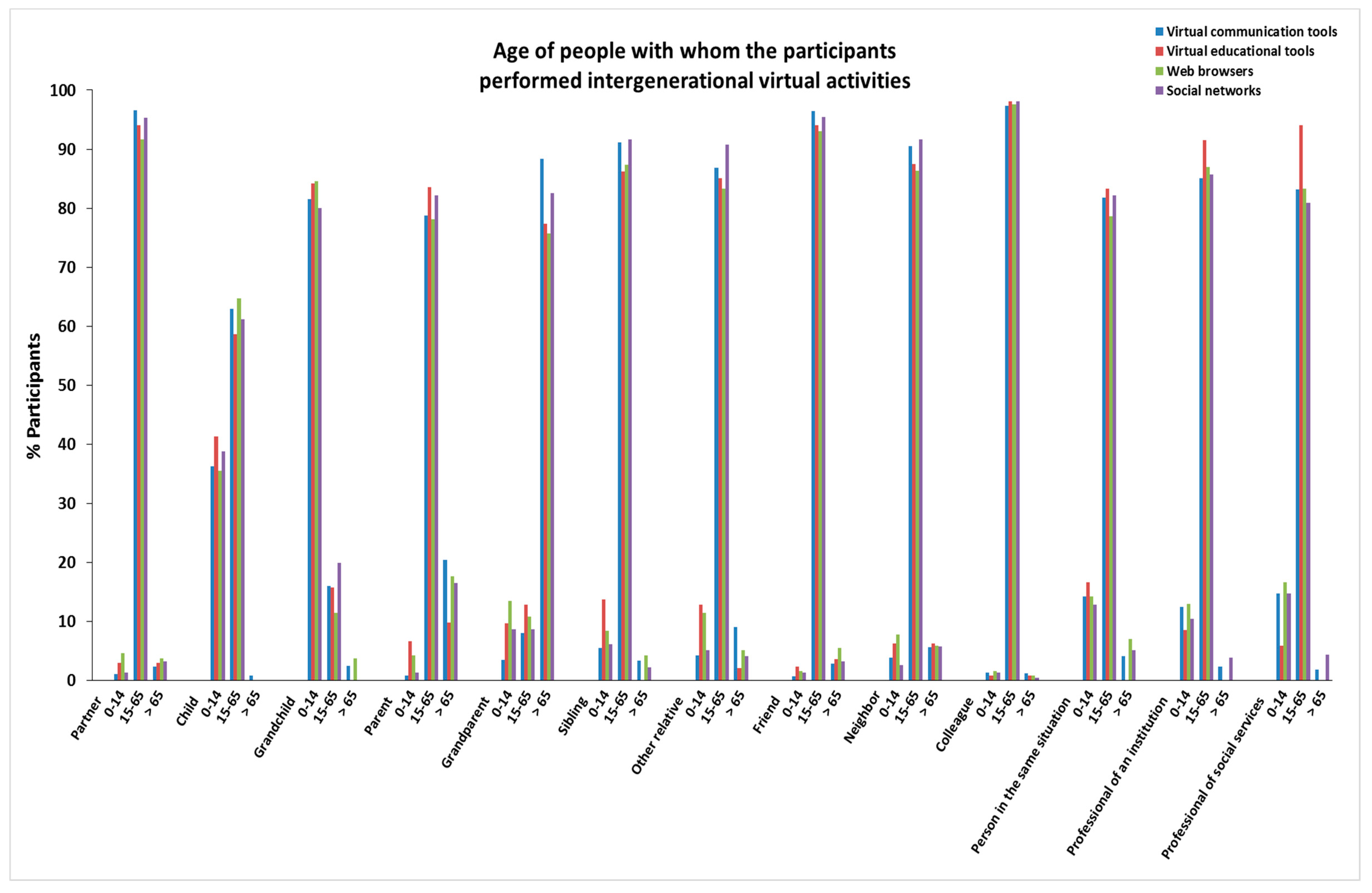

(C). AGE of the people with whom you use (1)/(2)/(3)/(4): Partner, Child, Grandchild, Parent, Grandparent, Sibling, Other relative, Friend, Neighbor, Colleague, Person in the same situation, Professional of an institution, Professional of health, social or academic services.

|

(D). SEX of the people with whom you use (1)/(2)/(3)/(4): Partner, Child, Grandchild, Parent, Grandparent, Sibling, Other relative, Friend, Neighbor, Colleague, Person in the same situation, Professional of an institution, Professional of health, social or academic services.

|

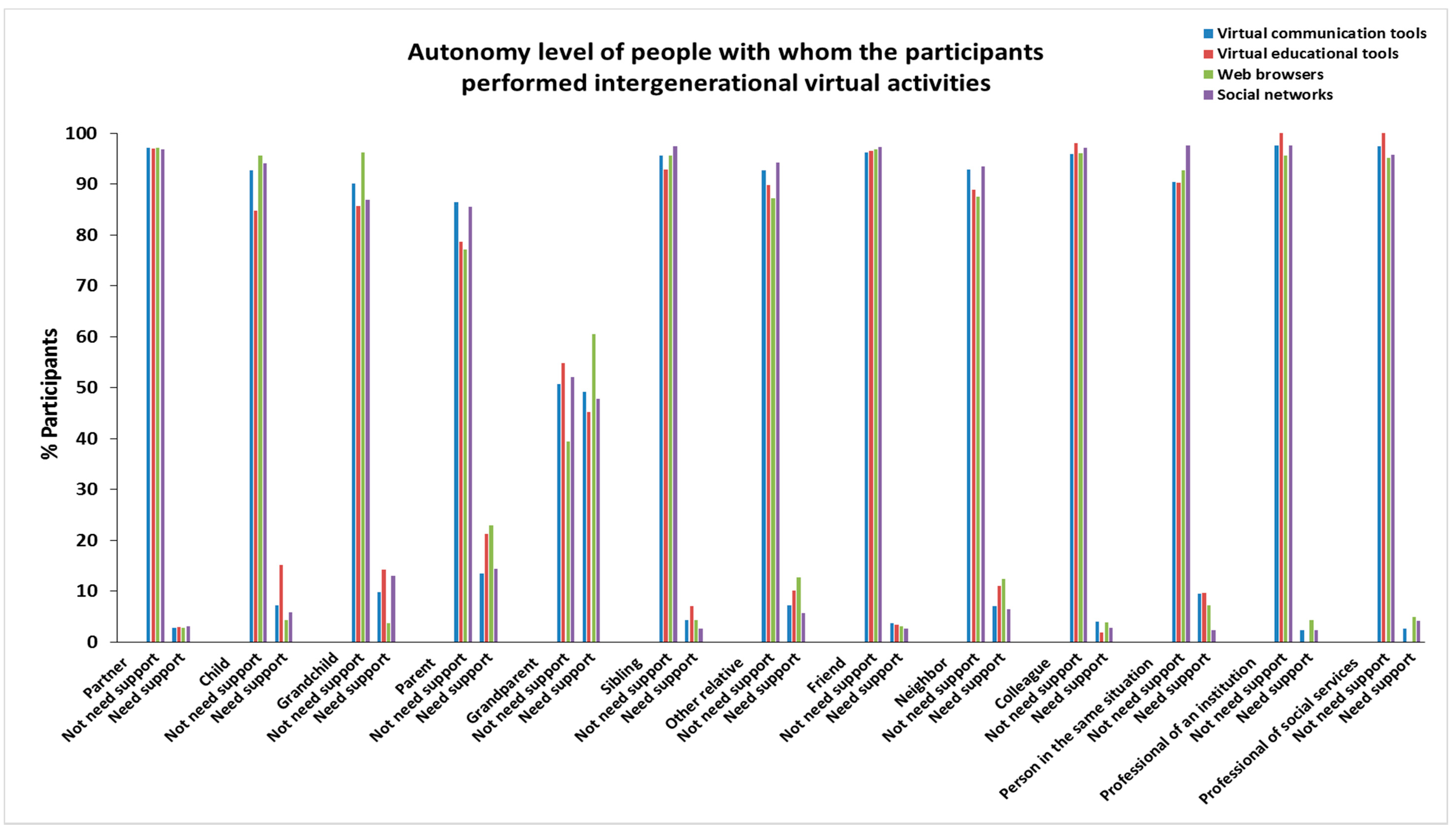

(E). AUTONOMY of the people with whom you use (1)/(2)/(3)/(4): Partner, Child, Grandchild, Parent, Grandparent, Sibling, Other relative, Friend, Neighbor, Colleague, Person in the same situation, Professional of an institution, Professional of health, social or academic services.

|

(F). LIMITATION of the people with whom you use (1)/(2)/(3)/(4): Partner, Child, Grandchild, Parent, Grandparent, Sibling, Other relative, Friend, Neighbor, Colleague, Person in the same situation, Professional of an institution, Professional of health, social or academic services.

|

(G). SATISFACTION you feel from using (1)/(2)/(3)/(4) with these people: Partner, Child, Grandchild, Parent, Grandparent, Sibling, Other relative, Friend, Neighbor, Colleague, Person in the same situation, Professional of an institution, Professional of health, social or academic services.

|

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.96 1 (16.01) 2 |

| Sex Male | 608 (30.2) |

| Female | 1405 (69.8) |

| Birthplace | |

| Rural area, small village | 440 (21.9) |

| Rural area, large village | 326 (16.2) |

| Urban area, small town | 906 (45.0) |

| Urban area, large town | 341 (16.9) |

| Education | |

| Primary school | 20 (1.0) |

| High school | 210 (10.4) |

| Vocational training | 138 (6.9) |

| College or university | 1645 (81.7) |

| Autonomy level | |

| Alone | 1705 (84.7) |

| Family support | 253 (12.6) |

| Professional support | 12 (0.6) |

| Other support | 43 (2.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 1024 (50.9) |

| Married or in union | 761 (37.8) |

| Widowed | 23 (1.1) |

| Separated | 25 (1.2) |

| Divorced | 56 (2.8) |

| Living arrangements | |

| Living alone | 205 (10.2) |

| Living with a partner | 332 (16.5) |

| Living with a partner and children | 342 (17.0) |

| Living with a partner and grandchildren | 3 (0.1) |

| Living with a partner, children, and grandchildren | 5 (0.2) |

| Living with children | 36 (1.8) |

| Living with children and grandchildren | 3 (0.1) |

| Living with parents | 562 (27.9) |

| Living with grandparents | 11 (0.5) |

| Living with parents and grandparents | 43 (2.1) |

| Living with other relatives | 43 (2.1) |

| Living with friends | 248 (12.3) |

| Other types | 180 (8.9) |

| Employment situation | |

| Unemployed | 938 (46.6) |

| Employed | 913 (45.4) |

| Retired | 151 (7.5) |

| Income level (EUR/month) | |

| >2500 | 862 (42.8) |

| 2001–2500 | 213 (10.6) |

| 1501–2000 | 264 (13.1) |

| 1001–1500 | 229 (11.4) |

| 501–1000 | 204 (10.1) |

| <500 | 116 (5.8) |

| Variables | Virtual Communication Tools (N = 895) | Virtual Educational Tools (N = 205) | Web Browsers (N = 239) | Social Networks (N = 417) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | χ2 | p | N (%) | χ2 | p | N (%) | χ2 | p | N (%) | χ2 | p | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| <22 22–39 ≥40 | 222 (25.1) 378 (42.3) 292 (32.7) | 5.055 | 0.088 | 58 (28.3) 81 (39.5) 66 (32.2) | 3.800 | 0.150 | 54 (22.6) | 1.294 | 0.524 | 123 (29.5) | 14.015 | 0.001 |

| 94 (39.3) | 167 (40.0) | |||||||||||

| 91 (38.1) | 127 (30.5) | |||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male Female | 259 (28.9) 636 (71.1) | 8.466 | 0.004 | 58 (28.3) 147 (71.7) | 1.858 | 0.173 | 70 (29.3) | 1.513 | 2.19 | 110 (26.4) | 10.034 | 0.002 |

| 169 (70.7) | 307 (73.6) | |||||||||||

| Place of origin | ||||||||||||

| Rural area Urban area | 157 (36.4) 274 (63.6) | 0.94 | 0.332 | 82 (40.0) 123 (60.0) | 1.447 | 0.229 | 90 (37.7) | 0.139 | 0.709 | 168 (40.3) | 4.308 | 0.038 |

| 149 (70.3) | 249 (59.7) | |||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than college or university College or university | 157 (17.5) 738 (82.5) | 2.604 | 0.107 | 36 (17.6) 169 (82.4) | 2.158 | 0.142 | 39 (16.3) | 0.672 | 0.412 | 79 (18.9) | 6.524 | 0.011 |

| 200 (83.7) | 338 (81.1) | |||||||||||

| Autonomy level | ||||||||||||

| Alone Family/profesional/other support | 868 (97.0) 27 (3.0) | 3.754 | 0.053 | 201 (98.0) 4 (2.0) | 0.037 | 0.848 | 235 (98.3) | 0.210 | 0.647 | 409 (98.1) | 0.182 | 0.670 |

| 4 (1.7) | 8 (1.9) | |||||||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Single Married or in union Widowed/separated/divorced | 433 (51.5) 359 (42.7) 49 (5.8) | 3.474 | 0.176 | 106 (57.0) 68 (36.6) 12 (6.5) | 5.869 | 0.053 | 113 (49.8) | 3.299 | 0.192 | 219 (55.4) | 11.420 | 0.003 |

| 99 (43.6) | 149 (37.7) | |||||||||||

| 15 (6.6) | 27 (6.8) | |||||||||||

| Living arrangements | ||||||||||||

| Living alone/with children/with grandchildren Living with a partner/a partner and children and/or grandchildren Living with parents and/or grandparents/ other relatives Living with friends/other types | 114 (12.7) 325 (36.3) 258 (28.8) 198 (22.1) | 9.560 | 0.023 | 28 (13.7) 69 (33.7) 60 (29.3) 48 (23.4) | 5.258 | 0.154 | 26 (10.9) | 4.813 | 0.186 | 51 (12.2) | 12.625 | 0.006 |

| 100 (41.8) | 136 (32.6) | |||||||||||

| 62 (25.9) | 132 (31.7) | |||||||||||

| 51 (21.3) | 98 (23.5) | |||||||||||

| Employment situation | ||||||||||||

| Unemployed Employed Retired | 415 (46.4) 411 (45.9) 69 (7.7) | 2.607 | 0.272 | 107 (52.2) 87 (42.4) 11 (5.4) | 3.632 | 0.163 | 99 (41.4) | 3.057 | 0.217 | 212 (50.8) | 9.527 | 0.009 |

| 119 (49.8) | 173 (41.5) | |||||||||||

| 21 (8.8) | 32 (7.7) | |||||||||||

| Income level (€/month) | ||||||||||||

| >2001 1001–2001 <1000 | 514 (57.4) 228 (25.5) 153 (17.1) | 0.660 | 0.719 | 124 (60.5) 45 (22.0) 36 (17.6) | 1.854 | 0.396 | 131 (54.8) | 0.292 | 0.864 | 256 (61.4) | 9.878 | 0.007 |

| 65 (27.2) | 105 (25.2) | |||||||||||

| 43 (18.0) | 56 (13.4) | |||||||||||

| Virtual Communication Tools N (%) | Virtual Educational Tools N (%) | Web Browsers N (%) | Social Networks N (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree | NA/ND | Agree | Disagree | NA/ND | Agree | Disagree | NA/ND | Agree | Disagree | NA/ND | Agree | |

| Physical health | 181 (25.5) | 349 (49.1) | 181 (25.5) | 52 (28.6) | 84 (46.2) | 46 (25.3) | 61 (29.6) | 88 (42.7) | 57 (27.7) | 97 (27.6) | 161 (45.9) | 93 (26.5) |

| Mental health | 62 (8.7) | 214 (30.1) | 435 (61.2) | 20 (11.0) | 73 (40.7) | 89 (48.9) | 28 (13.6) | 71 (34.5) | 107 (51.9) | 46 (13.1) | 100 (28.5) | 205 (58.4) |

| Mood | 35 (4.9) | 128 (18.0) | 548 (77.1) | 22 (12.1) | 65 (35.7) | 95 (52.2) | 24 (11.7) | 68 (33.0) | 114 (55.3) | 29 (8.3) | 68 (19.4) | 254 (72.4) |

| Relationships | 30 (4.2) | 81 (11.4) | 600 (84.4) | 18 (9.9) | 54 (29.7) | 110 (60.4) | 15 (7.3) | 52 (25.2) | 139 (67.5) | 19 (5.4) | 56 (16.0) | 276 (78.6) |

| Self- determination | 99 (13.9) | 311 (43.7) | 301 (42.3) | 23 (12.6) | 67 (36.8) | 92 (50.5) | 24 (11.7) | 79 (38.3) | 103 (50.0) | 56 (16.0) | 151 (43.0) | 144 (41.0) |

| Social participation | 42 (5.9) | 144 (20.3) | 525 (73.8) | 17 (9.2) | 49 (26.9) | 116 (63.7) | 17 (8.3) | 57 (27.7) | 132 (64.1) | 17 (4.8) | 60 (17.1) | 274 (78.1) |

| Economic well-being | 198 (27.8) | 374 (52.6) | 139 (19.5) | 41 (22.5) | 86 (47.3) | 55 (30.2) | 58 (28.2) | 98 (47.6) | 50 (24.3) | 110 (31.3) | 177 (50.4) | 64 (18.2) |

| Professional well-being | 138 (19.4) | 316 (44.4) | 257 (36.1) | 24 (13.2) | 54 (29.7) | 104 (57.1) | 28 (13.6) | 73 (35.4) | 105 (51.0) | 81 (23.1) | 154 (43.9) | 116 (33.0) |

| Academic education | 83 (11.7) | 280 (39.4) | 348 (48.9) | 10 (5.5) | 33 (18.1) | 139 (76.4) | 17 (8.3) | 54 (26.2) | 135 (65.5) | 56 (16.0) | 127 (36.2) | 168 (47.9) |

| Virtual Communication Tools N (%) | Virtual Educational Tools N (%) | Web Browsers N (%) | Social Networks N (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not/Little Satisfied | NA/ ND | Quite/ Very Satisfied | Not/ Little Satisfied | NA/ ND | Quite/ Very Satisfied | Not/ Little Satisfied | NA/ ND | Quite/ Very Satisfied | Not/ Little Satisfied | NA/ ND | Quite/ Very Satisfied | |

| Partner | 17 (3.6) | 58 (12.4) | 394 (84.0) | 5 (7.4) | 6 (8.8) | 57 (83.8) | 10 (8.6) | 18 (15.5) | 88 (75.9) | 14 (6.5) | 26 (12.0) | 177 (81.6) |

| Child | 30 (12.9) | 22 (9.4) | 181 (77.7) | 11 (13.4) | 8 (9.8) | 63 (76.8) | 12 (14.8) | 9 (11.1) | 60 (74.1) | 15 (15.3) | 16 (16.3) | 67 (68.4) |

| Grandchild | 27 (31.8) | 8 (9.4) | 50 (58.8) | 7 (31.8) | 2 (9.1) | 13 (59.1) | 11 (25.0) | 6 (13.6) | 27 (61.4) | 15 (31.9) | 7 (14.9) | 25 (53.2) |

| Parent | 18 (3.4) | 79 (15.1) | 426 (81.5) | 5 (8.5) | 8 (13.6) | 46 (78.0) | 9 (9.3) | 23 (23.7) | 65 (67.0) | 13 (6.3) | 46 (22.3) | 147 (71.4) |

| Grandparent | 4 (14.3) | 2 (7.1) | 22 (78.6) | 5 (16.1) | 2 (6.5) | 24 (77.4) | 8 (20.0) | 9 (22.5) | 23 (57.5) | 8 (11.3) | 11 (15.5) | 52 (73.2) |

| Sibling | 19 (3.9) | 63 (13.0) | 404 (83.1) | 5 (8.9) | 4 (7.1) | 47 (83.9) | 7 (7.4) | 14 (14.7) | 74 (77.9) | 12 (5.3) | 40 (17.5) | 176 (77.2) |

| Other relative | 15 (3.3) | 70 (15.6) | 365 (81.1) | 5 (10.0) | 7 (14.0) | 38 (76.0) | 6 (7.7) | 14 (17.9) | 58 (74.4) | 10 (4.7) | 40 (18.7) | 164 (76.6) |

| Friend | 8 (1.3) | 53 (8.8) | 542 (89.9) | 4 (4.7) | 13 (15.1) | 69 (80.2) | 5 (3.9) | 20 (15.6) | 103 (80.5) | 10 (3.3) | 39 (13.0) | 252 (83.7) |

| Neighbor | 16 (5.1) | 66 (21.0) | 233 (74.0) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (8.8) | 27 (79.4) | 9 (15.8) | 11 (19.3) | 37 (64.9) | 15 (9.1) | 35 (21.2) | 115 (69.7) |

| Colleague | 15 (3.2) | 82 (17.3) | 376 (79.5) | 9 (8.5) | 21 (19.8) | 76 (71.1) | 6 (4.8) | 22 (17.5) | 98 (77.8) | 6 (2.8) | 48 (22.6) | 158 (74.5) |

| Person in the same situation | 21 (14.8) | 27 (19.0) | 94 (66.2) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (12.5) | 22 (68.8) | 11 (26.8) | 4 (9.2) | 26 (63.4) | 12 (14.5) | 19 (22.9) | 52 (62.7) |

| Professional of an institution | 22 (13.8) | 41 (25.6) | 97 (60.6) | 8 (17.0) | 6 (12.8) | 33 (70.2) | 9 (18.8) | 9 (18.8) | 30 (62.5) | 13 (15.7) | 24 (28.9) | 46 (55.4) |

| Professional of social services | 25 (17.0) | 33 (22.4) | 89 (60.5) | 9 (13.2) | 10 (14.7) | 49 (72.1) | 9 (22.5) | 5 (12.5) | 26 (65.0) | 10 (14.3) | 14 (20.0) | 46 (65.7) |

| Virtual communication Tools N (%) | Virtual educational Tools N (%) | Web Browsers N (%) | Social Networks N (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Limitation | Any Limitation | No Limitation | Any Limitation | No Limitation | Any Limitation | No Limitation | Any Limitation | |

| Partner | 420 (91.7) | 38 (8.3) | 57 (83.8) | 11 (16.2) | 96 (88.1) | 13 (11.9) | 190 (88.0) | 26 (12.0) |

| Child | 210 (87.9) | 29 (12.1) | 37 (80.4) | 9 (19.6) | 61 (88.4) | 8 (11.6) | 88 (85.4) | 15 (14.6) |

| Grandchild | 75 (85.2) | 13 (14.8) | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 20 (76.9) | 6 (23.1) | 42 (82.4) | 9 (17.6) |

| Parent | 442 (85.0) | 78 (15.0) | 46 (76.7) | 14 (23.3) | 78 (78.8) | 21 (21.2) | 175 (84.1) | 33 (15.9) |

| Grandparent | 132 (65.0) | 71 (35.0) | 17 (53.1) | 15 (46.9) | 19 (50.0) | 19 (50.0) | 46 (62.2) | 28 (37.8) |

| Sibling | 435 (90.4) | 46 (9.6) | 49 (87.5) | 7 (12.5) | 83 (91.2) | 8 (8.8) | 199 (87.7) | 28 (12.3) |

| Other relative | 398 (90.2) | 43 (9.8) | 43 (89.6) | 5 (10.4) | 68 (87.2) | 10 (12.8) | 193 (89.4) | 23 (10.6) |

| Friend | 547 (92.6) | 44 (7.4) | 79 (92.9) | 6 (7.1) | 113 (89.7) | 13 (10.3) | 275 (91.7) | 25 (8.3) |

| Neighbor | 287 (90.0) | 32 (10.0) | 27 (79.4) | 7 (20.6) | 44 (80.0) | 11 (20.0) | 144 (84.7) | 26 (15.3) |

| Colleague | 423 (92.6) | 34 (7.4) | 99 (92.5) | 8 (7.5) | 116 (92.8) | 9 (7.2) | 190 (90.9) | 19 (9.1) |

| Person in the same situation | 127 (84.1) | 24 (15.9) | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | 33 (78.6) | 9 (21.4) | 70 (85.4) | 12 (14.6) |

| Professional of an institution | 139 (86.9) | 21 (13.1) | 43 (91.5) | 4 (8.5) | 36 (76.6) | 11 (23.4) | 70 (86.4) | 11 (13.6) |

| Professional of social services | 130 (87.8) | 18 (12.2) | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (80.0) | 8 (20.0) | 62 (84.9) | 11 (15.1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canedo-García, A.; García-Sánchez, J.-N.; Pacheco-Sanz, D.-I. Benefits, Satisfaction and Limitations Derived from the Performance of Intergenerational Virtual Activities: Data from a General Population Spanish Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010401

Canedo-García A, García-Sánchez J-N, Pacheco-Sanz D-I. Benefits, Satisfaction and Limitations Derived from the Performance of Intergenerational Virtual Activities: Data from a General Population Spanish Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010401

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanedo-García, Alejandro, Jesús-Nicasio García-Sánchez, and Deilis-Ivonne Pacheco-Sanz. 2022. "Benefits, Satisfaction and Limitations Derived from the Performance of Intergenerational Virtual Activities: Data from a General Population Spanish Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010401

APA StyleCanedo-García, A., García-Sánchez, J.-N., & Pacheco-Sanz, D.-I. (2022). Benefits, Satisfaction and Limitations Derived from the Performance of Intergenerational Virtual Activities: Data from a General Population Spanish Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010401