Non-Modifiable Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Military Personnel Undergoing Training: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

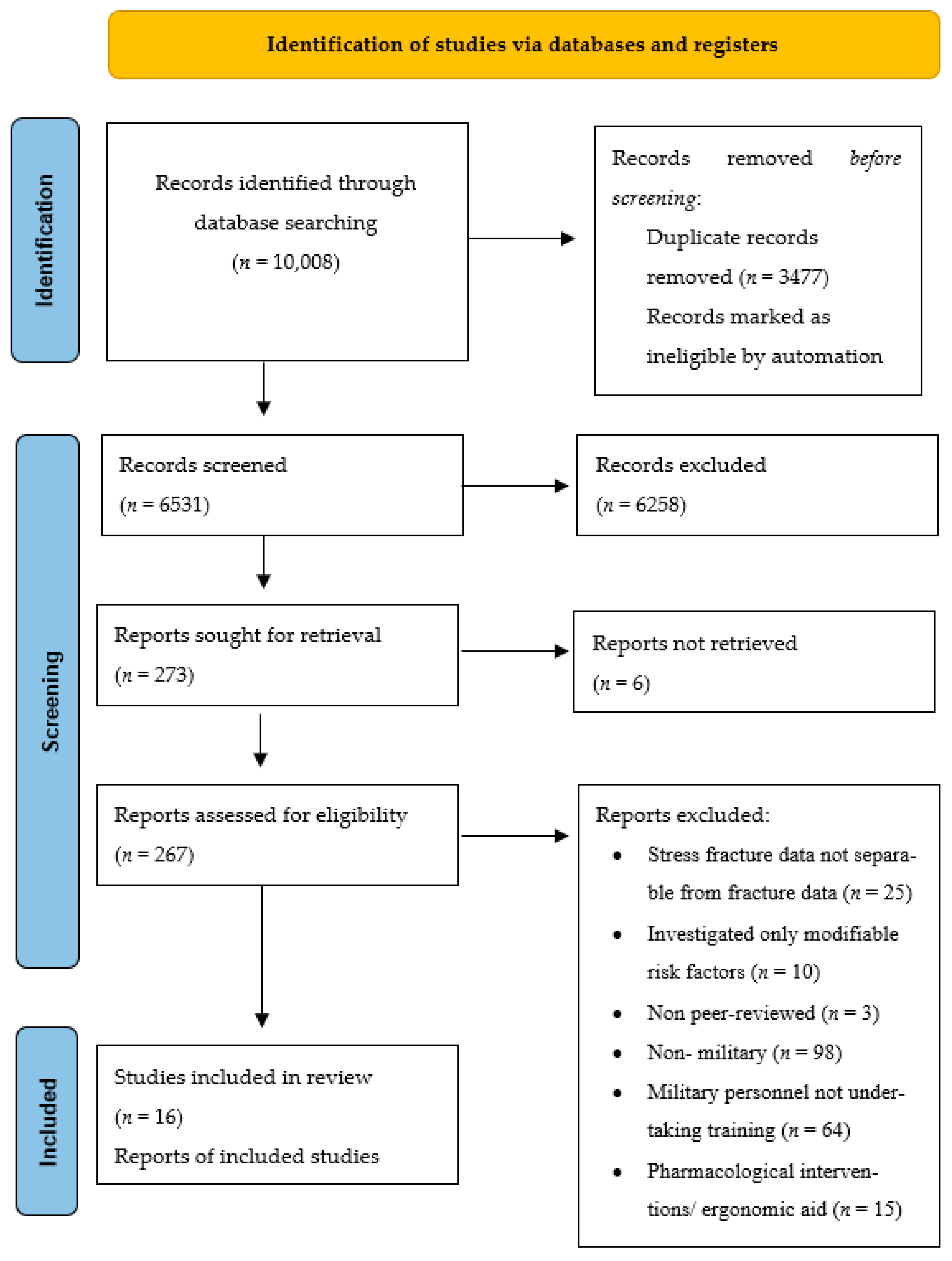

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Information Sources and Search

2.3. Eligibility Criteria, Screening and Selection

2.4. Methodological Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dixon, S.; Nunns, M.; House, C.; Rice, H.; Mostazir, M.; Stiles, V.; Davey, T.; Fallowfield, J.; Allsopp, A. Prospective study of biomechanical risk factors for second and third metatarsal stress fractures in military recruits. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, D.W., 3rd; Rue, J.P.; Wilckens, J.H.; Frassica, F.J. Stress fracture injury in young military men and women. Bone 2004, 35, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, J.; Montain, S.J.; McGraw, S.; Grier, T.; Ely, M.; Jones, B.H. Stress fracture risk factors in basic combat training. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 33, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.H.; Thacker, S.B.; Gilchrist, J.C.; Kimsey, D.J.; Sosin, D.M. Prevention of Lower Extremity Stress Fractures in Athletes and Soldiers: A Systematic Review. Epidemiol. Rev. 2002, 24, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, D.S.; Roth, M.; Kapil, N. Stress fractures: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 83, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Aweid, B.; Aweid, O.; Talibi, S.; Porter, K. Stress fractures. Trauma 2013, 15, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.M.; Cameron, K.L.; Bojescul, J.A. Lower Extremity Stress Fractures in the Military. Clin. Sports Med. 2014, 33, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh, M.J.; Macera, C.A.; Trone, D.W.; Shaffer, R.A.; Brodine, S.K. Epidemiology of Stress Fracture and Lower-Extremity Overuse Injury in Female Recruits. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunns, M.; House, C.; Rice, H.; Mostazir, M.; Davey, T.; Stiles, V.; Fallowfield, J.; Allsopp, A.; Dixon, S. Four biomechanical and anthropometric measures predict tibial stress fracture: A prospective study of 1065 Royal Marines. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, B.R.; Gun, B.; Bader, J.O.; Orr, J.D.; Belmont, P.J.; Belmont, P.J., Jr. Epidemiology of Lower Extremity Stress Fractures in the United States Military. Mil. Med. 2016, 181, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leslie, R.W.; Gumerman, L.W.; Hanley, E.N., Jr.; Williams Clark, M.; Goodman, M.; Herbert, D. Bone stress: A radionuclide imaging perspective. Radiology 1979, 132, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferer, K.R.; Bush, D.M.; Cornell, J.E.; Lawrence, V.A.; Alexander, J.L.; Ramos, R.G.; Curtis, D. Femoral neck stress fracture in Air Force basic trainees. Mil. Med. 2014, 179, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattila, V.M.; Niva, M.; Kiuru, M.; Pihlajamäki, H. Risk factors for bone stress injuries: A follow-up study of 102,515 person-years. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihlajamäki, H.; Parviainen, M.; Kyröläinen, H.; Kautiainen, H.; Kiviranta, I. Regular physical exercise before entering military service may protect young adult men from fatigue fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019, 20, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosman, F.; Ruffing, J.; Zion, M.; Uhorchak, J.; Ralston, S.; Tendy, S.; McGuigan, F.E.; Lindsay, R.; Nieves, J. Determinants of stress fracture risk in United States Military Academy cadets. Bone 2013, 55, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanchez-Santos, M.T.; Davey, T.; Leyland, K.M.; Allsopp, A.J.; Lanham-New, S.A.; Judge, A.; Arden, N.K.; Fallowfield, J.L. Development of a Prediction Model for Stress Fracture During an Intensive Physical Training Program: The Royal Marines Commandos. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2017, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krauss, M.R.; Garvin, N.U.; Cowan, D.N.; Boivin, M.R. Excess Stress Fractures, Musculoskeletal Injuries, and Health Care Utilization among Unfit and Overweight Female Army Trainees. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, R.A.; Rauh, M.J.; Brodine, S.K.; Trone, D.W.; Macera, C.A. Predictors of stress fracture susceptibility in young female recruits. Am. J. Sports Med. 2006, 34, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheinowitz, M.; Yanovich, R.; Sharvit, N.; Arnon, M.; Moran, D.S. Effect of cardiovascular and muscular endurance is not associated with stress fracture incidence in female military recruits: A 12-month follow up study. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 28, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finestone, A.; Milgrom, C.; Wolf, O.; Petrov, K.; Evans, R.; Moran, D. Epidemiology of metatarsal stress fractures versus tibial and femoral stress fractures during elite training. Foot Ankle Int. 2011, 32, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chang, Q.; Huang, T.; Huang, C. Prospective cohort study of the risk factors for stress fractures in Chinese male infantry recruits. J. Int. Med. Res. 2016, 44, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cowan, D.N.; Bedno, S.A.; Urban, N.; Lee, D.S.; Niebuhr, D.W. Step test performance and risk of stress fractures among female army trainees. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bar-Dayan, Y.; Gam, A.; Goldstein, L.; Karmon, Y.; Mintser, I.; Grotto, I.; Guri, A.; Goldberg, A.; Ohana, N.; Onn, E.; et al. Comparison of stress fractures of male and female recruits during basic training in the Israeli anti-aircraft forces. Mil. Med. 2005, 170, 710–712. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, H.M.; Saunders, S.C.; McGuire, S.J.; O’Leary, T.J.; Izard, R.M. Estimates of Tibial Shock Magnitude in Men and Women at the Start and End of a Military Drill Training Program. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, e392–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, E.W. Stress fractures of the pelvis in female Navy recruits: An analysis of possible mechanisms of injury. Mil. Med. 2000, 165, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dixon, S.J.; Creaby, M.W.; Allsopp, A.J. Comparison of static and dynamic biomechanical measures in military recruits with and without a history of third metatarsal stress fracture. Clin. Biomech. 2006, 21, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucera, K.L.; Marshall, S.W.; Wolf, S.H.; Padua, D.A.; Cameron, K.L.; Beutler, A.I. Association of Injury History and Incident Injury in Cadet Basic Military Training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Case-Control Checklist. 2020. Available online: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Case-Control-Study-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BJM 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffman, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BJM 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Cohort Study Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Cohort-Study-Checklist_2018.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Lappe, J.M.; Stegman, M.R.; Recker, R.R. The impact of lifestyle factors on stress fractures in female Army recruits. Osteoporos. Int. 2001, 12, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlajamäki, H.K.; Ruohola, J.P.; Kiuru, M.J.; Visuri, T.I. Displaced femoral neck fatigue fractures in military recruits. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sormaala, M.J.; Niva, M.H.; Kiuru, M.J.; Mattila, V.M.; Pihlajamäki, H.K. Stress injuries of the calcaneus detected with magnetic resonance imaging in military recruits. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2006, 88, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar]

- Yanovich, R.; Evans, R.K.; Friedman, E.; Moran, D.S. Bone turnover markers do not predict stress fracture in elite combat recruits. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 1365–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knapik, J.J.; Sharp, M.A.; Montain, S.J. Association between stress fracture incidence and predicted body fat in United States Army Basic Combat Training recruits. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018, 19, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Milgrom, C.; Finestone, A.; Shlamkovitch, N.; Rand, N.; Lev, B.; Simkin, A.; Wiener, M. Youth is a risk factor for stress fracture. A study of 783 infantry recruits. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1994, 76, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.H.; Cowan, D.N.; Tomlison, J.P.; Robinson, J.R.; Polly, D.W. Epidemiology of injuries associated with physical training among young men in the army. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, M.C. Racial differences in bone strength. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2007, 118, 305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger, B.; Sidney, S.; Cummings, S.R.; Libanati, C.; Bikle, D.D.; Tekawa, I.S.; Tolan, K.; Steiger, P. Racial Differences in Bone Density between Young Adult Black and White Subjects Persist after Adjustment for Anthropometric, Lifestyle, and Biochemical Differences. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, J.; Wright, K.; Kelly, M.; Zebrosky, B.; Zanis, M.; Drvol, C.; Butler, R. Injury risk is altered by previous injury: A systematic review of the literature and presentation of causative neuromuscular factors. Int. J. Sport Phys. Ther. 2014, 9, 583–595. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, R.; Pope, R.; Coyle, J.; Johnston, V. Self-reported load carriage injuries in australian regular army soldiers. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2016, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.J.; Ruff, C.B.; Shaffer, R.A.; Betsinger, K.; Trone, D.W.; Brodine, S.K. Stress fracture in military recruits: Gender differences in muscle and bone susceptibility factors. Bone 2000, 27, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.H.; Bovee, M.W.; Harris, J.M.; Cowan, D.N. Intrinsic risk factors for exercise related injuries among male and female Army trainees. Am. J. Sports Med. 1993, 21, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, R.M.; Pope, R.; Johnston, V.; Coyle, J. Soldier occupational load carriage: A narrative review of associated injuries. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2014, 21, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.; Knapik, J.J.; Pope, R. Avoiding Program-Induced Cumulative Overload (PICO). J. Spec. Oper. Med. A Peer Rev. J. SOF Med. Prof. 2016, 16, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, R.M.; Pope, R.P.; O’Shea, S.; Knapik, J.J. Load Carriage for Female Military Personnel. Strength Cond. J. 2020, 42, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzkin, E.; Curry, E.J.; Whitlock, K. Female athlete triad: Past, present, and future. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, P.; Lennox, G.; Schram, B.; Canetti, E.F.D.; Simas, V.; Pope, R.; Orr, R. Modifiable risk factors that increase the risk of fractures in military personnel undergoing training: A systematic review. J. Aust. Strength Cond. 2021. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Tenforde, A.; Sainani, K.; Sayres, L.; Milgrom, C.; Fredericson, M. Participation in Ball Sports May Represent a Prehabilitation Strategy to Prevent Future Stress Fractures and Promote Bone Health in Young Athletes. PMR 2015, 7, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattiv, A. Stress Fractures and Bone Health in Track and Field Athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2000, 3, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauers, S.; Scofield, D. Strength and Conditioning Strategies for Females in the Military. Strength Cond. J. 2014, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.K.; Antczak, A.J.; Lester, M.; Yanovich, R.; Israeli, E.; Moran, D.S. Effects of a 4-month recruit training program on markers of bone metabolism. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, S660–S670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.M.; Pope, R. Optimizing the Physical Training of Military Trainees. Strength Cond. J. 2015, 37, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Asi, N.; Alsawas, M.; Alahdab, F. New evidence pyramid. Evid. Based Med. 2016, 21, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Database | Search Terms | Filters |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((risk[Title/Abstract] OR predict * [Title/Abstract] OR prevalence[Title/Abstract] OR incidence[Title/Abstract] OR caus * [Title/Abstract] OR etiol * [Title/Abstract] OR frequenc * [Title/Abstract] OR rate * [Title/Abstract] OR mediat * [Title/Abstract] OR exposure * [Title/Abstract] OR likelihood[Title/Abstract] OR probability[Title/Abstract] OR factor[Title/Abstract] OR factors[Title/Abstract] OR hazard[Title/Abstract] OR hazards[Title/Abstract] OR predisposing[Title/Abstract])) AND ((work * [Title/Abstract] OR occupation * [Title/Abstract] OR profession * [Title/Abstract] OR trade[Title/Abstract] OR employ * [Title/Abstract] OR military[Title/Abstract] OR Defence[Title/Abstract] OR Defense[Title/Abstract] OR airforce[Title/Abstract] OR “air force”[Title/Abstract] OR army[Title/Abstract] OR navy[Title/Abstract] OR recruit[Title/Abstract] OR soldier * [Title/Abstract] OR marines[Title/Abstract] OR “Military Personnel”[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((Fracture * [Title/Abstract])) | Humans, English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French, Adolescent 13−18 years, Adults 19+ years, 2000−2020 |

| Reference | Study Type | Participants | Methods (Stress Fracture Diagnosis) | Occupational Training Program | Methodological Quality Rating (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosman et al. (2013) [15] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 891 | Orthopedist assessment X-ray | United States Military Academy Cadet Training | High (91) |

| U.S. Military Academy cadets | |||||

| Male: n = 755 | |||||

| Mean ± SD Age: 18.7 ± 0.8 years; | CT scan or MRI | ||||

| Female: n = 136 | |||||

| Mean ± SD Age: 18.4 ± 0.8 years | |||||

| Cowan et al. (2012) [22] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 1568 | At least two encounters with the same diagnosis, using ICD-9 codes 733.93 (tibia or fibula), 733.94 (metatarsals) and 733.95 (other bone) | Army Basic Training | Good (73) |

| Females entering the U.S. Army | |||||

| Dixon et al. (2018) [1] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 1065 | Not detailed | 32 Week Royal Marine Training Program | High (82) |

| UK Royal Marine recruits | |||||

| Knapik et al. (2012) [3] | Retrospective cohort | Total: n = 583,651 | ICD-9 codes | 10 weeks of basic training | High (100) |

| U.S. military recruits from databases of the Armed Forces Health Surveillance | |||||

| Females: n = 10,706 | |||||

| Males: n= 475,745 | |||||

| Knapik et al. (2018) [38] | Cross-sectional | Total: n = 583,651 | ICD-9 codes 733.1–733.19 and 733.93–733.98 | Army Basic Training | High (85) |

| U.S. military recruits | |||||

| Males: 475,745 | |||||

| Females: 107,906 | |||||

| Kucera et al. (2016) [27] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 9811 U.S. military cadets | ICD-9 codes | 2-month U.S. cadet Basic Training | Good (73) |

| Lappe et al. (2001) [34] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 3758 female U.S. military recruits | Clinical assessment X-ray or CT scan | 8-week U.S. Basic Military Training including: | High (82) |

| (1) March 225 km on gravel roads carrying a 10 kg pack and rifle | |||||

| (2) Run 135 km on asphalt roads | |||||

| (3) Approximately 1 h/day of physical training | |||||

| (4) Traverse an ‘agility course’ four times during the last 4 weeks | |||||

| Nunns et al. (2015) [9] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 1065 UK Royal Marine recruits | Medical examination | Royal Marine 32-week training program | Good (73) |

| Logistic regression analysis to assess potential risk factors focused on subsamples of recruits who sustained a tibial stress fracture (n = 10) and an injury-free group (n = 120) | MRI | ||||

| Pihlajamäki et al. (2019) [35] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 4029 male Finnish military recruits | ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis codes indicating stress fracture | 8 weeks of basic military training including: | High (82) |

| -17 h per week of combat skills, marching and other physically demanding training | |||||

| -Carrying heavy loads | |||||

| Pihlajamaki et al. (2006) [37] | Retrospective cohort | Total: n = 4029 male Finnish military recruits | Clinical examination | 8 weeks of basic military training including: | Good (73) |

| X-ray | -17 h per week of combat skills, marching and other physically demanding training | ||||

| MRI or CT scan | -Carrying heavy loads | ||||

| Rauh et al. (2006) [8] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 824 female U.S. Marine Corps recruits | Clinical examination | Marine Corps Recruit depot basic training | High (91) |

| X-ray | |||||

| CT scan | |||||

| Schaffer et al. (2006) [18] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 2962 female U.S. Marine Corps recruits | Clinical presentation with diagnostic imaging (X-ray, bone scan or both) | 13-week U.S Marine Corps basic training | High (82) |

| Aged 17–33 years | |||||

| Sanchez-Santos et al. (2017) [16] | Case-control | Total: n = 1082 UK Royal Marine recruits aged 16–33 years, including 86 cases with stress fractures | Clinical examination | 32 weeks of Royal Marine training | Good (77) |

| X-ray | |||||

| CT scan | |||||

| Scheinowitz et al. (2017) [19] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 226 female Israeli military recruits | Clinical examination | 16-month combat Army Basic Training program in the Israeli Defense Forces | Good (64) |

| X-ray | |||||

| CT scan | |||||

| Sormaala et al. (2006) [36] | Retrospective cohort | Total: n = 30 male Finnish military recruits, age range 18–26 years | Physical examination by orthopaedic surgeon | Military Training Program | High (82) |

| X-ray | |||||

| CT scan | |||||

| Zhao et al. (2016) [21] | Prospective cohort | Total: n = 1398 male Chinese infantry recruits | Clinical examination | 8-week training program including marching, running, training exercises and stationary standing procedures | High (82) |

| X-ray |

| Variable | Number of Studies | References |

| Age | 9 | [1,3,8,16,21,22,34,35,36] |

| Race | 6 | [3,18,22,34,38] |

| History of stress fracture | 4 | [8,18,21,27] |

| Height | 4 | [18,19,21,36] |

| History of musculoskeletal injury | 4 | [8,14,18,35] |

| Menstrual dysfunction | 3 | [8,15,18] |

| Kinathropometric attributes | 2 | [9,15] |

| Sex | 1 | [3] |

| Genotype | 1 | [21] |

| Study | Type of Fracture | Non-Modifiable Risk Factor | Key Findings | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosman et al. (2013). [15] | Stress fracture | Each additional year from menarche | ♂ OR (95% CI) | - | ||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.44 (1.19, 1.783) | |||||

| Diameter of femoral neck (mm) (each mm decrease) | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.35 (1.01, 1.81) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.16 (1.01, 1.33) | |||||

| Tibial BMC (mg) (each 10 mg decrease) | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.11 (1.03, 1.20) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.03 (0.92, 1.16) | |||||

| Tibial cortex cross-sectional area (each mm2 decrease) | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.12 (1.03, 1.23) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) | |||||

| Cowan et al. (2012) [22] | Stress fracture | Age (years) | 18–19 (reference) | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |

| 20–24 | 2.06 (1.32, 3.20) | |||||

| ≥25 | 3.07 (1.81, 5.19) | |||||

| Race | White (reference) | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Black | 0.68 (0.42, 1.12) | |||||

| Other | 0.97 (0.57, 1.66) | |||||

| Dixon et al. (2018) [1] | 2nd metatarsal fracture | Age (each additional year) | RRR (95% CI) | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | ||

| 3rd metatarsal fracture | Age (each additional year) | 0.78 (0.61–0.99) | ||||

| Knapik et al. (2012) [3] | Stress fracture | Age (years) | <20 years (reference) | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||||

| 20–24 | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.41 (1.34–1.48) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.47 (1.40–1.54) | |||||

| 25–29 | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.80 (1.67–1.93) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 2.33 (2.19–2.49) | |||||

| ≥30 | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 2.29 (2.09–2.51) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 3.50 (3.20–3.82) | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | White | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.54 (1.46–1.63) | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.74 (1.62–1.87) | |||||

| Black (reference) | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||||

| Hispanic | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.40 (1.30–1.52) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.58 (1.44–1.73) | |||||

| Asian | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.23 (1.08–1.41) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.29 (1.12–1.48) | |||||

| American Indian | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.39 (1.16–1.65) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.80 (1.46–2.21) | |||||

| Other | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.78 (1.30–2.44) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 2.08 (1.48–2.92) | |||||

| Unknown | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.20 (0.98–1.46) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.24 (0.99–1.55) | |||||

| Sex | Male | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Female | ♀ OR (95% CI) | 3.85 (3.66–5.05) | ||||

| Knapik et al. (2018) [38] | Race/ethnicity | Black (reference) | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | - | |

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | - | ||||

| White | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.72 (1.60–1.85) | <0.01 | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.54 (1.46–1.63) | <0.01 | ||||

| Hispanic | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.56 (1.43–1.71) | <0.01 | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.37 (1.27–1.48) | <0.01 | ||||

| Asian | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.38 (1.20–1.59) | <0.01 | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.28 (1.12–1.46) | <0.01 | ||||

| American Indian | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.75 (1.42–2.15) | <0.01 | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.37 (1.15–1.64) | <0.01 | ||||

| Other | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 2.12 (1.52–2.98) | <0.01 | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.77 (1.29–2.43) | <0.01 | ||||

| Unknown | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.31 (1.04–1.64) | 0.02 | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.23 (1.01–1.51) | 0.04 | ||||

| Kucera et al. (2016) [27] | No stress fracture history (reference) | Any history of injury to site | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||||

| History of injury to site with activity limitation | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||||

| Prior stress fracture | Any history of injury to site | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 3.58 (1.13–11.34) | |||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 17.03 (4.73–61.29) | |||||

| History of injury to site with activity limitation | ♂ OR (95% CI) | 6.06 (3.02–12.14) | ||||

| ♀ OR (95% CI) | 9.68 (3.91–23.95) | |||||

| Lappe et al. (2001) [34] | Age (for each additional year) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | 1.07 (1.04–1.1) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | White | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | 1.17 (1.06–1.30) | |||

| Black (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| All other races | 1.53 (1.02–2.28) | |||||

| Nunns et al. (2016) [9] | Tibial stress fracture | Bimalleolar width (mm) (for each 1 mm increase) | OR (95% CI) | 0.73 (0.58–0.93) | ||

| Threshold for avoiding stress fracture | >74 mm | |||||

| Peak heel pressure (N/cm2) (for each 1 N/cm2 increase) | OR (95% CI) | 1.25 (1.07–1.46) | ||||

| Threshold for avoiding stress fracture | <13 N/cm2 | |||||

| Tibial range of motion (°) (for each 1° increase) | OR (95% CI) | 0.78 (0.63–0.96) | ||||

| Threshold for avoiding stress fracture | >13° | |||||

| Pihlajamäki et al. (2019) [14] | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system | No disease history | IRR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||

| Disease history | 1.46 (0.57–3.70) | |||||

| Pihlajamaki et al. (2006) [35] | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system | No disease history | IRR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||

| Disease history | 1.36 (0.36–2.28) | |||||

| Rauh et al. (2006) [8] | Race/ethnicity | Black (reference) | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||

| Caucasian | 1.3 (0.6–2.7) | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.8 (0.3–2.2) | |||||

| Asian | 1.2 (0.2–5.9) | |||||

| American Indian/Other | 1.4 (0.3–6.7) | |||||

| Age (years) | 17–19 (reference) | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| >20 | 1.7 (0.8–3.6) | |||||

| History of lower extremity stress fracture | No (reference) | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 2.1 (0.8–5.5) | |||||

| History of lower extremity non-stress fracture injury | No (reference) | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | |||||

| Stress fracture | Secondary amenorrhea | No | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.7 (1.1–6.9) | |||||

| Sanchez-Santos et al. (2017) [16] | Age (years) | 19–23 | OR (95% CI) | 1.66 (0.97–2.85) | 0.66 | |

| 23–32 | 1.98 (1.07–3.55) | 0.30 | ||||

| Schaffer et al. (2006) [18] | Overall stress fracture | Race/ethnicity | Black | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |

| White | 1.54 (0.9–2.5) | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.97 (1.1–3.7) | |||||

| Asian | 2.28 (0.9–5.6) | |||||

| American Indian/other | 1.10 (0.3–3.6) | |||||

| Height (cm) | Shortest (≤157.26 cm) | OR (95% CI) | 1.30 (0.8–2.1) | |||

| Mean (163.77 cm) | 1.00 | |||||

| Tallest (≥170.29 cm) | 1.28 (0.8–2.1) | |||||

| History of stress fracture | No | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.78 (0.2–2.5) | |||||

| History of lower extremity injury | No | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.77 (0.5–1.1) | |||||

| Onset of menarche | ≤15 years old | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| 16 years or older | 1.29 (0.6–2.7) | |||||

| Menses during past year | 10–12 | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| 1–9 | 0.77 (0.5–1.3) | |||||

| None | 5.64 (2.2–14.4) | |||||

| Secondary amenorrhea during past year | No | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.66 (0.8–3.4) | |||||

| Pelvic or femoral stress fracture | Race/ethnicity | Black | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | ||

| White | 1.41 (0.7–2.9) | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.77 (0.7–4.4) | |||||

| Asian | 2.71 (0.8–9.0) | |||||

| American Indian/other | 1.50 (0.3–7.0) | |||||

| Height (cm) | Shortest (≤157.26 cm) | OR (95% CI) | 1.64 (0.9–3.1) | |||

| Mean (163.77 cm) | 1.00 | |||||

| Tallest (≥170.29 cm) | 1.40 (0.7–2.8) | |||||

| History of stress fracture | No | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.20 (0.3–4.9) | |||||

| History of lower extremity injury | No | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.71 (0.4–1.2) | |||||

| Onset of menarche | ≤15 years old | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| 16 years or older | 0.34 (0.1–2.4) | |||||

| Menses during past year | 10–12 | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| 1–9 | 1.25 (0.6–2.4) | |||||

| None | 8.54 (2.8–25.8) | |||||

| Secondary amenorrhea during past year | No | OR (95% CI) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 2.53 (1.1–6.0) | |||||

| Scheinowitz et al. (2017) [19] | Stress fracture | Mean ± SD Height (cm) | 166 ± 6 | 0.006 | ||

| No stress fracture | 162 ± 6 | |||||

| Sormaala et al. (2006) [36] | Height (cm) | 178 | No significant differences in the average height of participants with or without stress fractures (p > 0.1) | |||

| Age (years) | 18–27 | No significant differences in the average age of patients with or without stress fractures (p > 0.1) | ||||

| Zhao et al. (2016) [21] | Stress fracture | Genotypes | Codominant | OR (95% CI) | 1.76 (1.29–2.38) | p < 0.001 |

| TC | ||||||

| Dominant | 2.91 (1.25–6.74) | p = 0.013 | ||||

| CC | ||||||

| Recessive | 1.83 (1.33–2.52) | p < 0.001 | ||||

| CC þ TC | ||||||

| Mean ± SD Age (years) | OR (95% CI) | 18.5 ± 1.4 | NS (compared to no stress fracture) | |||

| Mean ± SD Height (cm) | 172.25 ± 5.67 | NS (compared to no stress fracture) | ||||

| Prior fracture (n (%)) | 28 (14.8%) | p = 0.01 (compared to no stress fracture) | ||||

| No stress fracture | Mean ± SD Age (years) | OR (95% CI) | 18.5 ± 1.8 | |||

| Mean ± SD Height (cm) | 171.78 ± 4.71 | |||||

| Prior fracture (n (%)) | 108 (8.9%) | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lennox, G.M.; Wood, P.M.; Schram, B.; Canetti, E.F.D.; Simas, V.; Pope, R.; Orr, R. Non-Modifiable Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Military Personnel Undergoing Training: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010422

Lennox GM, Wood PM, Schram B, Canetti EFD, Simas V, Pope R, Orr R. Non-Modifiable Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Military Personnel Undergoing Training: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010422

Chicago/Turabian StyleLennox, Grace M., Patrick M. Wood, Ben Schram, Elisa F. D. Canetti, Vini Simas, Rodney Pope, and Robin Orr. 2022. "Non-Modifiable Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Military Personnel Undergoing Training: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010422

APA StyleLennox, G. M., Wood, P. M., Schram, B., Canetti, E. F. D., Simas, V., Pope, R., & Orr, R. (2022). Non-Modifiable Risk Factors for Stress Fractures in Military Personnel Undergoing Training: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010422