Are People Optimistically Biased about the Risk of COVID-19 Infection? Lessons from the First Wave of the Pandemic in Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Is people’s perceived risk of infection absolutely or comparatively skewed? If so, do levels of optimism vary at each of the three (pre-, early and peak) pandemic stages within and across countries?

- Are there differences in comparative optimism among subpopulations?

- Is comparative optimism negatively associated with protective behaviours?

1.1. Optimism Bias in an Epidemic Context

1.2. Current Epidemiological Context

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Risk Perception

2.2.2. Unrealistic Optimism

2.2.3. Health-Protective Behaviours

2.2.4. Sociodemographic and Illness-Related Variables

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

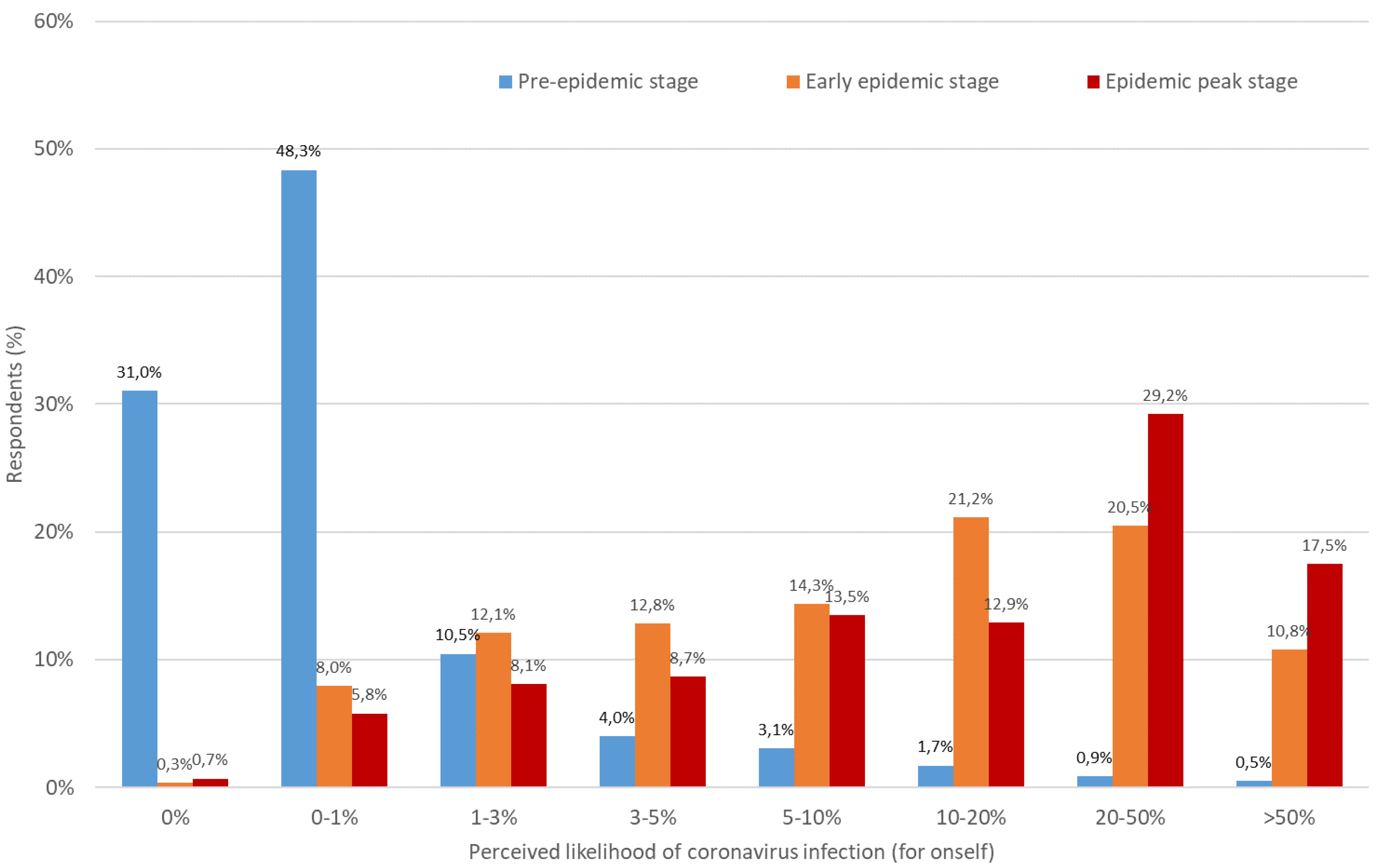

3.1. Are Perceived Risks of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Optimistically Biased?

3.2. Are There Differences in Comparative Optimism among Subpopulations?

3.3. Is Unrealistic Optimism Associated with the Adoption of Protective Behaviours?

4. Discussion

4.1. A Paradoxical Trend in Optimism

4.2. Potential Explanations for Paradoxical Findings

4.3. Comparative Optimism and Health-Protective Behaviours

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19); Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Raude, J.; Debin, M.; Souty, C.; Guerrisi, C.; Turbelin, C.; Falchi, A.; Colizza, V. Are people excessively pessimistic about the risk of coronavirus infection? PsyArXiv 2020, 10. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, T.; Zbozinek, T.D.; Michelini, G.; Hagan, C.C. Changes in risk perception and protective behavior during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, B.M. Reasons for noncompliance with infection control guidelines. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2000, 21, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H. Adherence to health messages: A social psychological perspective. Int. Dent. J. 2000, 50, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Kumar, A. Responses to health promotion campaigns: Resistance, denial and othering. Crit. Public Health 2011, 21, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, A.; Michie, S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrer, R.A.; Klein, W.M. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J. The global emergence/resurgence of arboviral diseases as public health problems. Arch. Med. Res. 2002, 33, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioral science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- World Health Organisation. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Ooi, E.E.; Vasudevan, S.G.; Gubler, D.J. Update on dengue: Epidemiology, virus evolution, antiviral drugs, and vaccine development. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2010, 12, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Weinstein, N.D.; Cuite, C.L.; Herrington, J.E. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 27, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 335–383. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Setbon, M.; Raude, J. Population response to the risk of vector-borne diseases: Lessons learned from socio-behavioral research during large-scale outbreaks. Emerg. Health Threats J. 2009, 2, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.J.; Zhang, Z.; Usborne, E.; Guan, Y. Optimism across cultures: In response to the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 7, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Klein, W.M.; Waters, E.A.; Weinstein, N.D. Taking stock of unrealistic optimism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. J. Behav. Med. 1982, 5, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Accuracy of smokers’ risk perceptions. Ann. Behav. Med. 1998, 20, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoy, D.M. The optimism bias and traffic accident risk perception. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1989, 21, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covey, J.A.; Davies, A.D. Are people unrealistically optimistic? It depends how you ask them. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, F.P. It won’t happen to me: Unrealistic optimism or illusion of control? Br. J. Psychol. 1993, 84, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. Cognitive and psychological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In Social Psychophysiology: A Sourcebook; Cacioppo, J.T., Petty, R.E., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.J.; Klein, W.M.; Weinstein, N.D. Absolute and Relative Biases in Estimations of Personal Risk. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 26, 1213–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, D.R.; Quine, L.; Albery, I.P. Perceptions of risk in motorcyclists: Unrealistic optimism, relative realism and predictions of behavior. Br. J. Psychol. 1998, 89, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Waters, E.A.; Weinstein, N.D.; Klein, W.M. A primer on unrealistic optimism. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 24, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Nicolich, M. Correct and incorrect interpretations of correlations between risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Health Psychol. 1993, 12, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, N.C.; Amand, M.D.S.; Poole, G.D. The controllability of negative life experiences mediates unrealistic optimism. Soc. Indic. Res. 1997, 42, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T. The optimism bias. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R941–R945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Klotz, M.L.; Sandman, P.M. Optimistic biases in public perceptions of the risk from radon. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, N.D. Why it won’t happen to me: Perceptions of risk factors and susceptibility. Health Psychol. 1984, 3, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Klein, W.M. Unrealistic optimism: Present and future. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.A.; Klein, W.M.; Moser, R.P.; Yu, M.; Waldron, W.R.; McNeel, T.S.; Freedman, A.N. Correlates of unrealistic risk beliefs in a nationally representative sample. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 34, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Lyon, J.E. Mindset, optimistic bias about personal risk and health-protective behavior. Br. J. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanian, J.Z.; Cleary, P.D. Perceived risks of heart disease and cancer among cigarette smokers. JAMA 1999, 281, 1019–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cummings, K.M.; Becker, M.H.; Maile, M.C. Bringing the models together: An empirical approach to combining variables used to explain health actions. J. Behav. Med. 1980, 3, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Helweg-Larsen, M.; Shepperd, J.A. Do moderators of the optimistic bias affect personal or target risk estimates? A review of the literature. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 5, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenbaum, M. Do smokers understand the mortality effects of smoking? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Survey. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems: Conclusions from a community-wide sample. J. Behav. Med. 1987, 10, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, N.M.; Klein, W.M. Dispositional, unrealistic, and comparative optimism: Differential relations with the knowledge and processing of risk information and beliefs about personal risk. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorens, V.; Buunk, B.P. Social Comparison of Health Risks: Locus of Control, the Person-Positivity Bias, and Unrealistic Optimism. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Reis, T.J.; Gerrard, M.; Luus, C.E.; Sufka, A.V.W. Perceptions of smoking risk as a function of smoking status. J. Behav. Med. 1992, 15, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Sandman, P.M.; Roberts, N.E. Determinants of self-protective behavior: Home radon testing. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 20, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science 1989, 246, 1232–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, J.A.; Pogge, G.; Howell, J.L. Assessing the consequences of unrealistic optimism: Challenges and recommendations. Conscious. Cog. 2017, 50, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, Y.; Giladi, E.E. Are most people happier than their peers, or are they just happy? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, W.M.; Weinstein, N.D. Social comparison and unrealistic optimism about personal risk. In Health, Coping, and Well-Being: Perspectives from Social Comparison Theory; Buunk, B.P., Gibbons, F.X., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sandman, P.M.; Weinstein, N.D. Communicating Effectively about Risk Magnitudes: Bottom Line Conclusions and Recommendations for Practitioners; Risk Communication Project, Office of Policy, Planning and Evaluation, US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/40000KXI.PDF?Dockey=40000KXI.PDF (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Tam, K.P.; Lau, I.; Chiu, C. Biases in the perceived prevalence and motives of severe acute respiratory syndrome prevention behaviors among Chinese high school students in Hong Kong. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 7, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, A.; Bortolotti, L.; Kuzmanovic, B. What is unrealistic optimism? Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 50, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bränström, R.; Kristjansson, S.; Ullen, H. Risk perception, optimistic bias, and readiness to change sun related behavior. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 16, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatfield, J.; Job, R.S. Optimism bias about environmental degradation: The role of the range of impact of precautions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Reducing unrealistic optimism about illness susceptibility. Health Psychol. 1983, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raude, J.; McColl, K.; Flamand, C.; Apostolidis, T. Understanding health behavior changes in response to outbreaks: Findings from a longitudinal study of a large epidemic of mosquito-borne disease. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 230, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zwart, O.; Veldhuijzen, I.K.; Elam, G.; Aro, A.R.; Abraham, T.; Bishop, G.D.; Voeten, H.A.; Richardus, J.H.; Brug, J. Perceived threat, risk perception, and efficacy beliefs related to SARS and other (emerging) infectious diseases: Results of an international survey. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 16, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuper-Smith, B.J.; Doppelhofer, L.M.; Oganian, Y.; Rosenblau, G.; Korn, C. Risk perception and optimism during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 8, 210904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, P.; Shepherd, R.; Wieringa, N.; Zimmermanns, N. Perceived behavioral control, unrealistic optimism and dietary change: An exploratory study. Appetite 1995, 24, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Niederdeppe, J. The role of emotional response during an H1N1 influenza pandemic on a college campus. J. Public Relat. Res. 2013, 25, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravert, R.D.; Fu, L.Y.; Zimet, G.D. Reasons for low pandemic H1N1 2009 vaccine acceptance within a college sample. Adv. Prev. Med. 2012, 2012, 242518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S. Optimistic bias about H1N1 flu: Testing the links between risk communication, optimistic bias, and self-protection behavior. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudisill, C. How do we handle new health risks? Risk perception, optimism, and behaviors regarding the H1N1 virus. J. Risk Res. 2013, 16, 959–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Peng, Z. People at risk of influenza pandemics: The evolution of perception and behavior. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettori, M.; Arghittu, A.; Deiana, G.; Azara, A.; Masia, M.D.; Palmieri, A.; Spano, A.L.; Serra, A.; Castiglia, P. Influenza Vaccination Strategies in Healthcare Workers: A Cohort Study (2018–2021) in an Italian University Hospital. Vaccines 2021, 9, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine; Coronavirus Resource Center. Cumulative Cases. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/cumulative-cases (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Lau, J.T.F.; Yang, X.; Tsui, H.; Kim, J.H. Monitoring community responses to the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: From day 10 to day 62. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesza, W.; Dolinski, D.; Muniak, P.; Derakhshan, A.; Rizulla, A.; Banach, M. We are infected with the new, mutated virus UO-COVID-19. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolinski, D.; Dolinska, B.; Zmaczynska-Witek, B.; Banach, M.; Kulesza, W. Unrealistic optimism in the time of coronavirus pandemic: May it help to kill, if so—Whom: Disease or the person? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmunds, W.J.; Eames, K.; Keogh-Brown, M. Capturing human behavior: Is it possible to bridge the gap between data and models? In Modeling the Interplay between Human Behavior and the Spread of Infectious Diseases; Manfredi, P., D’Onofrio, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, N. Capturing human behavior. Nature 2007, 446, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liò, P.; Lucia, B.; Nguyen, V.A.; Kitchovitch, S. Risk perception, heuristics and epidemic spread. In Modeling the Interplay between Human Behavior and the Spread of Infectious Diseases; Manfredi, P., D’Onofrio, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, P.; D’Onofrio, A. (Eds.) Modeling the Interplay between Human Behavior and the Spread of Infectious Diseases; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mansdorf, I.J.; Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Enforcing Compliance with COVID-19 Pandemic Restrictions: Psychological Aspects of a National Security Threat. Available online: https://jcpa.org/article/enforcing-compliance-with-covid-19-pandemic-restrictions-psychological-aspects-of-a-national-security-threat/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Symptoms of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine. Johns Hopkins ABX Guides: Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.hopkinsguides.com/hopkins/view/Johns_Hopkins_ABX_Guide/540143/all/Coronavirus (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine; Coronavirus Resource Center. Hubei Timeline. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/hubei-timeline (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Assessing Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 Illness. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/assessing-risk-factors.html (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Johns Hopkins University of Medicine; Coronavirus Resource Center. New Cases of COVID-19 in World Countries. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/new-cases (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Hasell, J. Our World in Data: Statistics and Research: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Salzberger, B.; Buder, F.; Lampl, B.; Ehrenstein, B.; Hitzenbichler, F.; Holzmann, T.; Schmidt, B.; Hanses, F. Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. Infection 2020, 49, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut Pasteur. COVID-19 Disease (Novel Coronavirus). Available online: https://www.pasteur.fr/en/medical-center/disease-sheets/covid-19-disease-novel-coronavirus (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- World Health Organisation. Advice on the Use of Masks in the Context of COVID-19. Interim Guidance. 6 April 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331693/WHO-2019-nCov-IPC_Masks-2020.3-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- The Lancet. COVID-19 vaccines: No time for complacency. Lancet 2020, 396, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): How to Protect Yourself and Others. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- White, D.B.; Lo, B. A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 1773–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Optimism and health-related cognition: What variables actually matter? Psychol. Health 1994, 9, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, L.; Pullano, G.; Sabbatini, C.E.; Boëlle, P.Y.; Colizza, V. Impact of lockdown in Île-de-France and possible exit strategies. BMC Med. 2020, 18(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Langen, H. The Impact of Response Measures on COVID-19-Related Hospitalization and Death Rates in Germany and Switzerland. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.11278. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.11278.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, G. COVID-19: UK lockdown is “crucial” to saving lives, say doctors and scientists. BMJ 2020, 368, m1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanfelici, M. The Italian Response to the COVID-19 Crisis: Lessons Learned and Future Direction in Social Development. Int. J. Community Soc. Dev. 2020, 2, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobías, A. Evaluation of the lockdowns for the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Italy and Spain after one month follow up. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.E.; Brown, J.D. Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Pligt, J. Risk perception and self-protective behavior. Eur. Psychol. 1996, 1, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrisi, C.; Turbelin, C.; Blanchon, T.; Hanslik, T.; Bonmarin, I.; Levy-Bruhl, D.; Perrotta, D.; Paolotti, D.; Smallenburg, R.; Koppeschaar, C.; et al. Participatory syndromic surveillance of influenza in Europe. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, S386–S392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brooks-Pollock, E.; Tilston, N.; Edmunds, W.J.; Eames, K.T. Using an online survey of healthcare-seeking behaviour to estimate the magnitude and severity of the 2009 H1N1v influenza epidemic in England. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ung, A.; Baidjoe, A.Y.; Van Cauteren, D.; Fawal, N.; Fabre, L.; Guerrisi, C.; Danis, K.; Morand, A.; Donguy, M.P.; Lucas, E.; et al. Disentangling a complex nationwide Salmonella Dublin outbreak associated with raw-milk cheese consumption, France, 2015 to 2016. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1700703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dolinski, D.; Gromski, W.; Zawisza, E. Unrealistic pessimism. J. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 127, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debin, M.; Turbelin, C.; Blanchon, T.; Bonmarin, I.; Falchi, A.; Hanslik, T.; Levy-Bruhl, D.; Poletto, C.; Colizza, V. Evaluating the feasibility and participants’ representativeness of an online nationwide surveillance system for influenza in France. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Eurostat 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/home (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- United Nations Statistics Division. UN Data a World of Information Statistics: Population 15 Years of Age and over, by Educational Attainment, Age and Sex 2020. Available online: http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=POP&f=tableCode%3A30 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques. Diplôme le plus élevé selon l’âge et le sexe, données annuelles 2019. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2416872 (accessed on 28 December 2020). (In French)

- Federal Statistical Office Confedération Suisse. Statistics. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics.html (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Instituto Nazionale di Statistica. Education and Training. Available online: https://www.istat.it/en/education-and-training (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanet, A.; Cauchemez, S. COVID-19 herd immunity: Where are we? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vena, A.; Berruti, M.; Adessi, A.; Blumetti, P.; Brignole, M.; Colognato, R.; Gaggioli, G.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Bracci-Laudiero, L.; Magnasco, L.; et al. Prevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in Italian adults and associated risk factors. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringhini, S.; Wisniak, A.; Piumatti, G.; Azman, A.S.; Lauer, S.A.; Baysson, H.; De Ridder, D.; Petrovic, D.; Schrempft, S.; Marcus, K.; et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Geneva, Switzerland (SEROCoV-POP): A population-based study. Lancet 2020, 396, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, H.; Atchison, C.J.; Whitaker, M.; Ainslie, K.E.; Elliot, J.; Okell, L.C.; Redd, R.; Ashby, D.; Doonnelly, C.A.; Barclay, W.; et al. Antibody prevalence for SARS-CoV-2 in England following first peak of the pandemic: REACT2 study in 100,000 adults. MedRxiv 2020. BMJ Yale. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottemanne, H.; Morlaàs, O.; Fossati, P.; Schmidt, L. Does the Coronavirus Epidemic Take Advantage of Human Optimism Bias? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, A.J.; Hahn, U. Unrealistic optimism about future life events: A cautionary note. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 118, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, P.; Harris, A.J.; Bird, G.; Catmur, C.; Hahn, U. A pessimistic view of optimistic belief updating. Cog. Psychol. 2016, 90, 71–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nowroozpoor, A.; Choo, E.K.; Faust, J.S. Why the United States failed to contain COVID-19. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2020, 1, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut de Recherche pour le Développement France; l’Agence Nationale de la Recherche. Coronavirus et CONfinement: Enquête Longitudinale Note de synthèse, vague 1, Méditerranée Infection, COCONEL Group. Available online: https://www.mediterranee-infection.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Note-n1-confinement-conditions-de-vie.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021). (In French)

- Hertwig, R.; Pachur, T.; Kurzenhäuser, S. Judgments of risk frequencies: Tests of possible cognitive mechanisms. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2005, 31, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachur, T.; Hertwig, R.; Rieskamp, J. The mind as an intuitive pollster: Frugal search in social spaces. In Simple Heuristics in a Social World; Hertwig, A., Hoffrage, U., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 261–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pachur, T.; Rieskamp, J.; Hertwig, R. The social circle heuristic: Fast and frugal decisions based on small samples. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Chicago, IL, USA, 4–7 August 2004; Forbus, K., Gentner, D., Regier, T., Eds.; California Digital Library, University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 26. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hg79025 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Price, P.C.; Pentecost, H.C.; Voth, R.D. Perceived event frequency and the optimistic bias: Evidence for a two-process model of personal risk judgments. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T. The Optimism Bias: Why We’re Wired to Look on the Bright Side; Hachette: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/affect (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. The affect heuristic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 1333–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R.B. Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Ju, I.; Ohs, J.E.; Hinsley, A. Optimistic bias and preventive behavioral engagement in the context of COVID-19. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditto, P.H.; Jemmott, J.B., III; Darley, J.M. Appraising the threat of illness: A mental representational approach. Health Psychol. 1988, 7, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress, coping and illness. In Personality and Disease; Friedman, H.S., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 168, pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, H. Findings and theory in the study of fear communications. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Volume 5, pp. 119–186. [CrossRef]

- Helweg-Larsen, M. (The lack of) optimistic biases in response to the 1994 Northridge earthquake: The role of personal experience. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armor, D.A.; Taylor, S.E. Situated optimism: Specific outcome expectancies and self-regulation. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 30, 309–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P. Sufficient grounds for optimism?: The relationship between perceived controllability and optimistic bias. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 15, 9–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E.; Armor, D.A. Positive illusions and coping with adversity. J. Pers. 1996, 64, 873–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragkaki, I.; Maciejewski, D.F.; Weijman, E.; Feltes, J.; Cima, M. Human Responses to Covid-19: The Role of Optimism Bias, Perceived Severity, and Anxiety. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2020, 176, 110781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IZA Institute of Labor Economics. Crisis Response Monitoring Country Report: Italy. Available online: https://covid-19.iza.org/crisis-monitor/italy/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- L’Observatoire Société et Consommation (L’Obsoco). Recherches: Enquête sur les impacts du confinement sur la mobilité et les modes de vie des Français, avril 2020. Available online: https://fr.forumviesmobiles.org/projet/2020/04/23/enquete-sur-impacts-confinement-sur-mobilite-et-modes-vie-des-francais-13285 (accessed on 15 December 2021). (In French).

- Mc Kinsey & Company. COVID-19 in the UK: Assessing Jobs at Risk and the Impact on People and Places. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-in-the-united-kingdom-assessing-jobs-at-risk-and-the-impact-on-people-and-places# (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Statista. Contact Frequency during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Switzerland in 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1110509/coronavirus-covid-19-contact-frequency-switzerland/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Statista. Mobility Reduction Due to COVID_19 in Italy in March 2020, by Region. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1111049/mobility-reduction-due-to-covid-19-in-italy-by-region/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Statista. Outside Contact Location during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Switzerland in 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1110512/coronavirus-covid-19-contact-location-ouside-switzerland/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Statista. Professional Situation of French People Confined Following the COVID-19 Epidemic 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1108512/activity-professional-containment-france/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

| Survey Question | Possible Answers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Perception | ||||||||

| What is the risk for yourself of catching this coronavirus in the coming weeks? | 0% | 0–1% | 1–3% | 3–5% | 5–10% | 10–20% | 20–50% | >50% |

| In your opinion, out of 100 [name of country] people, how many of them are at risk of catching this coronavirus in the coming weeks? | 0% | 0–1% | 1–3% | 3–5% | 5–10% | 10–20% | 20–50% | >50% |

| I think I already had this disease. [Survey 3 only] | Yes | No | ||||||

| Protective Behaviours | ||||||||

| Which of the following do you do as a result of this coronavirus? | ||||||||

| Wash your hands often | Yes | No | ||||||

| Wear a face mask | Yes | No | ||||||

| Avoid touching your mouth or nose | Yes | No | ||||||

| Use a tissue only once when coughing or sneezing | Yes | No | ||||||

| Avoid public transportation | Yes | No | ||||||

| Use sanitizing hand gel | Yes | No | ||||||

| Avoid contact with people who look sick | Yes | No | ||||||

| Avoid social events | Yes | No | ||||||

| Risk Perception | Survey 1 | Survey 2 | Survey 3 | C2 (df), p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Optimism | 47.4% (120) | 59.2% (155) | 74.6% (296) | 104 (4), <10−5 |

| Realism | 47.0% (119) | 26.3% (69) | 11.8% (47) | ||

| Pessimism | 5.5% (14) | 14.5% (38) | 13.6% (54) | ||

| France | Optimism | 55.4% (1880) | 38.7% (1012) | 67.2% (2536) | 927 (4), <10−5 |

| Realism | 39.2% (1329) | 42.5% (1110) | 16.2% (611) | ||

| Pessimism | 5.4% (184) | 18.8% (492) | 16.6% (627) | ||

| Switzerland | Optimism | 40.8% (158) | 39.5% (92) | 61.8% (252) | 96 (4), <10−5 |

| Realism | 9.3% (36) | 42.1% (98) | 18.6% (76) | ||

| Pessimism | 49.9% (193) | 18.5% (43) | 19.6% (80) | ||

| United Kingdom | Optimism | 39.4% (54) | 44.8% (107) | 72.2% (200) | 85 (4), <10−5 |

| Realism | 56.2% (77) | 40.6% (97) | 15.5% (43) | ||

| Pessimism | 4.4% (6) | 14.6% (35) | 12.3% (34) | ||

| All | Optimism | 53.0% (2213) | 40.8% (1366) | 67.2% (2536) | 1135 (4), <10−5 |

| Realism | 41.2% (1718) | 41.0% (1374) | 16.6% (627) | ||

| Pessimism | 5.8% (241) | 18.2% (608) | 16.2% (611) | ||

| Variable | Optimism %(N) | Realism %(N) | Pessimism %(N) | C2 (df), p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 50.9% (3013) | 14.8% (874) | 34.3% (2031) | 95 (2), <10−5 |

| Female | 59.6% (3851) | 11.9% (770) | 28.5% (1838) | ||

| Age group | 18–35 | 50.5% (1622) | 14.5% (465) | 35.1% (1127) | 63 (4), <10−5 |

| 35–65 | 56.1% (3481) | 12.6% (779) | 31.4% (1946) | ||

| 65 and older | 59.6% (1761) | 13.5% (400) | 26.9% (796) | ||

| Occupation | Employed | 51.9% (3433) | 13.7% (907) | 34.4% (2280) | 96 (6), <10−5 |

| Unemployed | 64.9% (674) | 10.9% (113) | 24.2% (251) | ||

| Retired | 58.4% (2349) | 13.1% (526) | 28.6% (1149) | ||

| Student | 58.7% (273) | 14.6% (68) | 26.7% (124) | ||

| Other | 59% (135) | 12.7% (29) | 28.4% (65) | ||

| Education | Some high school | 58.2% (1647) | 15.1% (428) | 26.7% (757) | 102 (4), <10−5 |

| High school | 58.7% (2690) | 12.2% (560) | 29.1% (1331) | ||

| Some college and higher | 50.9% (2527) | 13.2% (655) | 35.9% (1781) | ||

| Composition of household | Living with one or several children | 54.7% (1616) | 14.7% (433) | 30.6% (904) | 6 (4), 0.18 |

| Living with other adults but no child | 55.5% (3935) | 12.9% (913) | 31.6% (2239) | ||

| Living alone | 55.9% (1288) | 12.9% (298) | 31.2% (718) | ||

| Missing data | 74.3% (26) | 2.9% (1) | 22.9% (8) | ||

| Health status | No chronic health condition | 55.5% (5228) | 12.4% (1173) | 32.1% (3025) | 30 (2), <10−5 |

| Chronic health condition | 55.4% (1635) | 16% (471) | 28.6% (844) | ||

| Country | Switzerland | 48.8% (502) | 15.5% (160) | 35.7% (367) | 40 (6), <10−5 |

| France | 55.5% (5429) | 13.3% (1303) | 31.2% (3051) | ||

| Italy | 62.7% (572) | 11.6% (106) | 25.7% (235) | ||

| United Kingdom | 55.3% (361) | 11.5% (75) | 33.2% (217) | ||

| Survey | Pre-epidemic stage | 53% (2213) | 5.8% (241) | 41.2% (1718) | 1131 (4), <10−5 |

| Early epidemic stage | 40.8% (1366) | 18.2% (608) | 41% (1374) | ||

| Epidemic peak stage | 67.6% (3285) | 16.4% (795) | 16% (777) |

| Variable | UOR (95% CI) | p-Value | AOR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Female | 1.39 [1.27;1.51] | <0.001 | 1.4 [1.29;1.52] | <0.001 | |

| Age group | 18–35 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| 35–65 | 1.10 [0.94;1.28] | 0.050 | 1.09 [0.93;1.27] | 0.048 | |

| >65 | 1.28 [1.04;1.58] | 0.050 | 1.27 [1.04;1.57] | 0.048 | |

| Occupation | Employed | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Unemployed | 1.32 [1.11;1.57] | 0.003 | 1.3 [1.1;1.55] | 0.003 | |

| Retired | 1.18 [1.01;1.36] | 0.003 | 1.17 [1.02;1.35] | 0.003 | |

| Student | 1.28 [0.91;1.82] | 0.003 | 1.29 [0.92;1.83] | 0.003 | |

| Education | High school | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Some high school | 1.11 [0.95;1.29] | 0.001 | 1.1 [0.95;1.28] | <0.001 | |

| Some college and higher | 0.89 [0.8;0.99] | 0.001 | 0.88 [0.79;0.98 | <0.001 | |

| Stage | Pre-epidemic | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Early epidemic | 0.76 [0.69;0.83] | <0.001 | 0.76 [0.69;0.84] | <0.001 | |

| Epidemic peak | 2.38 [2.17;2.61] | <0.001 | 2.38 [2.17;2.61] | <0.001 | |

| Country | Switzerland | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| France | 1.29 [1.11;1.49] | <0.001 | 1.29 [1.11;1.49] | <0.001 | |

| Italy | 1.81 [1.47;2.22] | <0.001 | 1.82 [1.48;2.23] | <0.001 | |

| United Kingdom | 1.21 [0.97;1.51] | <0.001 | 1.22 [0.98;1.53] | <0.001 | |

| Composition of household | Living with other adult(s), without a child | Ref. | |||

| Living alone | 0.97 [0.87;1.09] | 0.607 | |||

| Living with one or several children | 0.95 [0.85;1.05] | 0.607 | |||

| Health status | No chronic health condition | Ref. | |||

| Chronic health condition | 0.92 [0.84;1.01] | 0.097 |

| Health Behaviour | AOR and 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Wash hands often | 0.89 [0.77;1.03] | 0.13 |

| Wear face mask | 0.65 [0.54;0.78] | <0.0001 |

| Avoid touching one’s mouth and nose | 0.86 [0.75;0.99] | 0.041 |

| Use a unique tissue when coughing or sneezing | 0.9 [0.79;1.03] | 0.12 |

| Avoid public transportation | 1.1 [0.96;1.26] | 0.16 |

| Use sanitising hand gel | 0.75 [0.67;0.86] | <0.0001 |

| Avoid contact with people who look sick | 1.15 [1.01;1.31] | 0.036 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McColl, K.; Debin, M.; Souty, C.; Guerrisi, C.; Turbelin, C.; Falchi, A.; Bonmarin, I.; Paolotti, D.; Obi, C.; Duggan, J.; et al. Are People Optimistically Biased about the Risk of COVID-19 Infection? Lessons from the First Wave of the Pandemic in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010436

McColl K, Debin M, Souty C, Guerrisi C, Turbelin C, Falchi A, Bonmarin I, Paolotti D, Obi C, Duggan J, et al. Are People Optimistically Biased about the Risk of COVID-19 Infection? Lessons from the First Wave of the Pandemic in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010436

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcColl, Kathleen, Marion Debin, Cecile Souty, Caroline Guerrisi, Clement Turbelin, Alessandra Falchi, Isabelle Bonmarin, Daniela Paolotti, Chinelo Obi, Jim Duggan, and et al. 2022. "Are People Optimistically Biased about the Risk of COVID-19 Infection? Lessons from the First Wave of the Pandemic in Europe" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010436

APA StyleMcColl, K., Debin, M., Souty, C., Guerrisi, C., Turbelin, C., Falchi, A., Bonmarin, I., Paolotti, D., Obi, C., Duggan, J., Moreno, Y., Wisniak, A., Flahault, A., Blanchon, T., Colizza, V., & Raude, J. (2022). Are People Optimistically Biased about the Risk of COVID-19 Infection? Lessons from the First Wave of the Pandemic in Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010436