Links of Perceived Pornography Realism with Sexual Aggression via Sexual Scripts, Sexual Behavior, and Acceptance of Sexual Coercion: A Study with German University Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Pornography Use, Perceived Realism and Sexual Aggression

1.2. Pornography Use, Risky Sexual Scripts, and Risky Sexual Behavior

1.3. Pornography Use and Acceptance of Sexual Coercion

1.4. The Role of Gender

1.5. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Frequency of Use and Perception of Pornography as Realistic

2.2.2. Risky Sexual Scripts

2.2.3. Risky Sexual Behavior

2.2.4. Acceptance of Sexual Coercion

2.2.5. Sexual Aggression Victimization and Perpetration

2.3. Procedure and Plan of Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results and Correlations

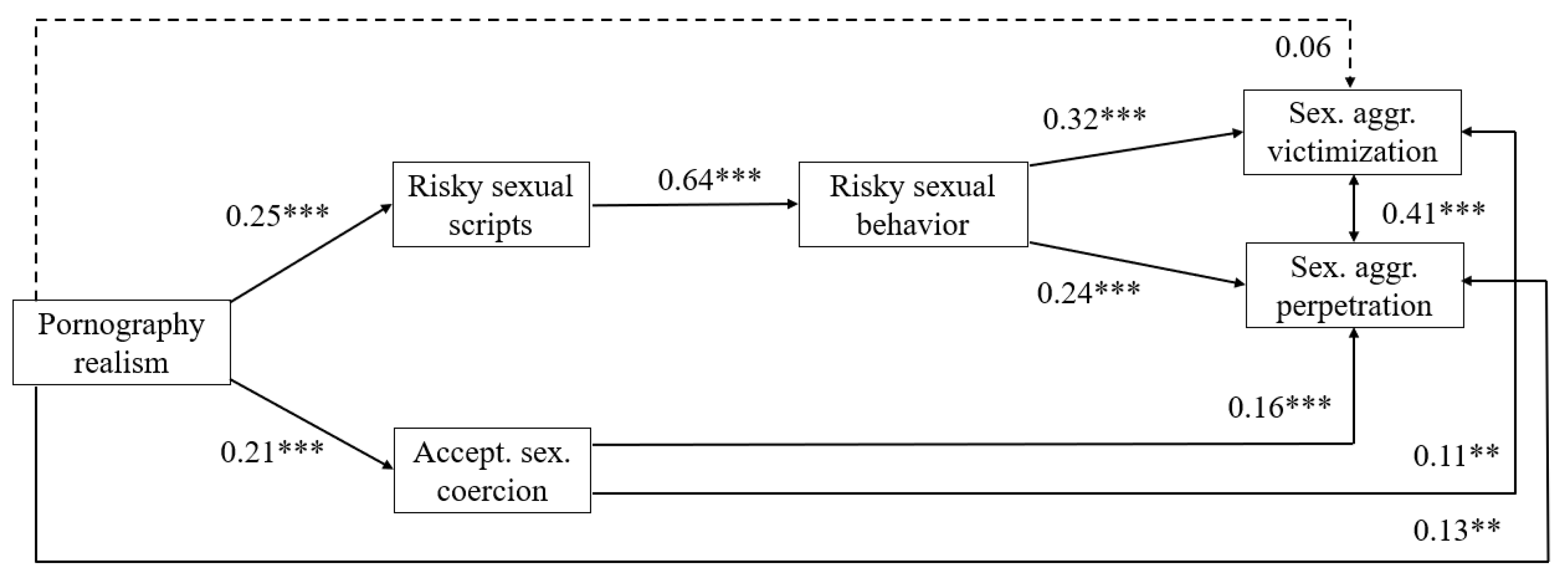

3.2. Path Analyses

4. Discussion

Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Victimization

- 1.

- Has a man ever made (or tried to make) you have sexual contact with him against your will by threatening to use force or by harming you (e.g., by hurting you, holding you down or threatening to do so)?

- (a)

- My current or former partner in a steady relationship to engage in…… sexual touch… attempted intercourse… completed intercourse… other sexual acts (e.g., oral sex)

- (b)

- A friend or acquaintance to engage in…… sexual touch… attempted intercourse… completed intercourse… other sexual acts (e.g., oral sex)

- (c)

- A stranger (e.g., someone I met at a club) to engage in…… sexual touch… attempted intercourse… completed intercourse… other sexual acts (e.g., oral sex)(Yes or No answers to each item)

- 2.

- Has a man ever made (or tried to make) you have sexual contact with him against your will by exploiting the fact that you were unable to resist (e.g., after you had had too much alcohol or drugs)?… + items (a), (b), (c) as above

- 3.

- Has a man ever made (or tried to make) you have sexual contact with him against your will by putting verbal pressure on you (e.g., by threatening to end the relationship or spreading lies)?… + items (a), (b), (c) as above

Appendix A.2. Perpetration: Same Items from the Actor Perspective

References

- Eljawad, M.A.; Se’Eda, H.; Ghozy, S.; El-Qushayri, A.E.; Elsherif, A.; Elkassar, A.H.; Atta-Allah, M.H.; Ibrahim, W.; Elmahdy, M.A.; Islam, S.M.S. Pornography Use Prevalence and Associated Factors in Arab Countries: A Multinational Cross-Sectional Study of 15,027 Individuals. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, J.; Patterson, R.; Regnerus, M.; Walley, J. How Much More XXX is Generation X Consuming? Evidence of Changing Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Pornography Since 1973. J. Sex Res. 2015, 53, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissel, C.; Richters, J.; de Visser, R.; McKee, A.; Yeung, A.; Caruana, T. A Profile of Pornography Users in Australia: Findings From the Second Australian Study of Health and Relationships. J. Sex Res. 2017, 54, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggisberg, M. Sexually explicit video games and online pornography—The promotion of sexual violence: A critical commentary. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 53, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.; Byron, P.; Litsou, K.; Ingham, R. An Interdisciplinary Definition of Pornography: Results from a Global Delphi Panel. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, D.J.; Raggatt, P.T.F.; McBain, K. A Literature Review of Studies into the Prevalence and Frequency of Men’s Pornography Use. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2020, 15, 502–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald, G.M.; Seaman, C.; Linz, D. Sexuality and pornography. In APA Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology; Tolman, D.L., Diamond, L.M., Bauermeister, J.A., George, W., Pfaus, J.G., Ward, L.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hornor, G. Child and Adolescent Pornography Exposure. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2020, 34, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rothman, E.F.; Beckmeyer, J.J.; Herbenick, D.; Fu, T.-C.; Dodge, B.; Fortenberry, J.D. The Prevalence of Using Pornography for Information About How to Have Sex: Findings from a Nationally Representative Survey of U.S. Adolescents and Young Adults. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M. Youth Viewing Sexually Explicit Material Online: Addressing the Elephant on the Screen. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2012, 10, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, N.; Paul, B. From Orgasms to Spanking: A Content Analysis of the Agentic and Objectifying Sexual Scripts in Feminist, for Women, and Mainstream Pornography. Sex Roles 2017, 77, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, A.J.; Wosnitzer, R.; Scharrer, E.; Sun, C.; Liberman, R. Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis Update. Violence Against Women 2010, 16, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shor, E. Age, Aggression, and Pleasure in Popular Online Pornographic Videos. Violence Against Women 2019, 25, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, M.; Canan, S.N.; Jozkowski, K.N.; Bridges, A.J. Sexual Consent Communication in Best-Selling Pornography Films: A Content Analysis. J. Sex Res. 2019, 57, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahé, B.; Tomaszewska, P.; Kuyper, L.; Vanwesenbeeck, I. Prevalence of sexual aggression among young people in Europe: A review of the evidence from 27 EU countries. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J.; Tokunaga, R.S.; Kraus, A. A Meta-Analysis of Pornography Consumption and Actual Acts of Sexual Aggression in General Population Studies. J. Commun. 2015, 66, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Abreu, L.C.F.; Krahé, B. Vulnerability to Sexual Victimization in Female and Male College Students in Brazil: Cross-Sectional and Prospective Evidence. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 45, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Heer, B.; Prior, S.; Fejervary, J. Women’s Pornography Consumption, Alcohol Use, and Sexual Victimization. Violence Against Women 2021, 27, 1678–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, P.; Krahé, B. Predictors of Sexual Aggression Victimization and Perpetration Among Polish University Students: A Longitudinal Study. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J.; Hartley, R.D. Pornography and Sexual Aggression: Can Meta-Analysis Find a Link? Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 23, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohut, T.; Landripet, I.; Štulhofer, A. Testing the Confluence Model of the Association Between Pornography Use and Male Sexual Aggression: A Longitudinal Assessment in Two Independent Adolescent Samples from Croatia. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 50, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, K.; Tafro, A.; Stulhofer, A. Adolescent sexual aggressiveness and pornography use: A longitudinal assessment. Aggress. Behav. 2019, 45, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgogna, N.C.; Lathan, E.C.; McDermott, R.C. She Asked for It: Hardcore Porn, Sexism, and Rape Myth Acceptance. Violence Against Women 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Processes Underlying the Effects of Adolescents’ Use of Sexually Explicit Internet Material: The Role of Perceived Realism. Commun. Res. 2010, 37, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J.; Sun, C.; Steffen, N. Pornography Consumption, Perceptions of Pornography as Sexual Information, and Condom Use. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2018, 44, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baams, L.; Overbeek, G.; Dubas, J.S.; Doornwaard, S.M.; Rommes, E.; Van Aken, M.A.G. Perceived Realism Moderates the Relation Between Sexualized Media Consumption and Permissive Sexual Attitudes in Dutch Adolescents. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2014, 44, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wright, P.J.; Paul, B.; Herbenick, D. Preliminary Insights from a U.S. Probability Sample on Adolescents’ Pornography Exposure, Media Psychology, and Sexual Aggression. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.S.; Williams, C.J.; Kleiner, S.; Irizarry, Y. Pornography, Normalization, and Empowerment. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2010, 39, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, W.; Gagnon, J.H. Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1986, 15, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littleton, H.L.; Dodd, J.C. Violent Attacks and Damaged Victims. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 1725–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmstead, S.B.; Norona, J.C.; Anders, K.M. How Do College Experience and Gender Differentiate the Enactment of Hookup Scripts Among Emerging Adults? Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 1769–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, P.J. Mass Media Effects on Youth Sexual Behavior Assessing the Claim for Causality. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2011, 35, 343–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J.; Bae, S. Pornography and male socialization. In APA Handbook of Men and Masculinities; Wong, Y.J., Wester, S.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 551–568. [Google Scholar]

- Krahé, B.; Berger, A. Pathways from College Students’ Cognitive Scripts for Consensual Sex to Sexual Victimization: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, I.; Tomaszewska, P.; Krahé, B. Changing Cognitive Risk Factors for Sexual Aggression: Risky Sexual Scripts, Low Sexual Self-Esteem, Perception of Pornography, and Acceptance of Sexual Coercion. J. Interpers. Violence 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J. A Longitudinal Analysis of US Adults’ Pornography Exposure. J. Media Psychol. 2012, 24, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Marcantonio, T.L.; Rhoads, K.E.; Canan, S.; Hunt, M.E.; Willis, M. A Content Analysis of Sexual Consent and Refusal Communication in Mainstream Films. J. Sex Res. 2019, 56, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, E.; Bulck, J.V.D. Casual Sexual Scripts on the Screen: A Quantitative Content Analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 1481–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- D’Abreu, L.C.F.; Krahé, B. Predicting sexual aggression in male college students in Brazil. Psychol. Men Masc. 2014, 15, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, P.; Krahé, B. Attitudes towards sexual coercion by Polish high school students: Links with risky sexual scripts, pornography use, and religiosity. J. Sex. Aggress. 2016, 22, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bridges, A.J.; Sun, C.F.; Ezzell, M.B.; Johnson, J. Sexual Scripts and the Sexual Behavior of Men and Women Who Use Pornography. Sex. Media Soc. 2016, 2, 237462381666827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald, G.M.; Kuyper, L.; Adam, P.C.; de Wit, J.B. Does Viewing Explain Doing? Assessing the Association Between Sexually Explicit Materials Use and Sexual Behaviors in a Large Sample of Dutch Adolescents and Young Adults. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 2986–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkness, E.L.; Mullan, B.; Blaszczynski, A. Association Between Pornography Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors in Adult Consumers: A Systematic Review. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, R.S.; Wright, P.J.; E Roskos, J. Pornography and Impersonal Sex. Hum. Commun. Res. 2018, 45, 78–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henderson, E.; Aaron, S.; Blackhurst, Z.; Maddock, M.; Fincham, F.; Braithwaite, S.R. Is Pornography Consumption Related to Risky Behaviors during Friends with Benefits Relationships? J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 2446–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodenhizer, K.A.E.; Edwards, K.M. The Impacts of Sexual Media Exposure on Adolescent and Emerging Adults’ Dating and Sexual Violence Attitudes and Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence Abus. 2017, 20, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnay, J.; Kepes, S.; Bushman, B.J. Effects of violent and nonviolent sexualized media on aggression-related thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Aggress. Behav. 2022, 48, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, A. A Meta-analysis of Media Consumption and Rape Myth Acceptance. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, J.; McMahon, S.; Cusano, J.; Seabrook, R.; Gracey, L. Predictors of campus sexual violence perpetration: A systematic review of research, sampling, and study design. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021, 58, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, D.; Benbouriche, M.; Bonneville, V. A Meta-Analysis on the Association Between Rape Myth Acceptance and Sexual Coercion Perpetration. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarche, V.M.; Seery, M.D. Come on, give it to me baby: Self-esteem, narcissism, and endorsing sexual coercion following social rejection. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 149, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.M. Adolescents and Pornography: A Review of 20 Years of Research. J. Sex Res. 2016, 53, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wright, P.J.; Stulhofer, A. Adolescent pornography use and the dynamics of perceived pornography realism: Does seeing more make it more realistic? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koletić, G.; Stulhofer, A.; Tomić, I.; Ćuća, J.K. Associations between Croatian Adolescents’ Use of Sexually Explicit Material and Risky Sexual Behavior: A Latent Growth Curve Modeling Approach. Int. J. Sex. Health 2019, 31, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, H.; Esgalhado, G. Sexually Explicit Online Media Use and Sexual Behavior among Sexual Minority Men in Portugal. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, T.H.F.; Rendina, H.J.; Grov, C.; Parsons, J.T. Sexually Explicit Media and Condomless Anal Sex Among Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS Behav. 2017, 22, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahé, B.; Bieneck, S.; Scheinberger-Olwig, R. The Role of Sexual Scripts in Sexual Aggression and Victimization. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2006, 36, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahé, B.; Berger, A. Men and women as perpetrators and victims of sexual aggression in heterosexual and same-sex encounters: A study of first-year college students in Germany. Aggress. Behav. 2013, 39, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koss, M.P.; Abbey, A.; Campbell, R.; Cook, S.; Norris, J.; Testa, M.; Ullman, S.; West, C.; White, J. Revising the SES: A Collaborative Process to Improve Assessment of Sexual Aggression and Victimization. Psychol. Women Q. 2007, 31, 357–370, Erratum in Psychol. Women Q. 2008, 32, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahé, B.; Berger, A.; Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Bianchi, G.; Chliaoutakis, J.; Fernández-Fuertes, A.A.; Fuertes, A.; de Matos, M.G.; Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Haller, B.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of young people’s sexual aggression perpetration and victimisation in 10 European countries: A multi-level analysis. Cult. Health Sex. 2015, 17, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahé, B.; de Haas, S.; Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Bianchi, G.; Chliaoutakis, J.; Fuertes, A.; de Matos, M.G.; Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Hellemans, S.; Kouta, C.; et al. Interpreting Survey Questions About Sexual Aggression in Cross-Cultural Research: A Qualitative Study with Young Adults from Nine European Countries. Sex. Cult. 2016, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuster, I.; Tomaszewska, P.; Marchewka, J.; Krahé, B. Does Question Format Matter in Assessing the Prevalence of Sexual Aggression? A Methodological Study. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewska, P.; Schuster, I.; Marchewka, J.; Krahé, B. Order Effects of Presenting Coercive Tactics on Young Adults’ Reports of Sexual Victimization. J. Interpers. Violence 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.M.; Murphy, M.J.; Gidycz, C.A. Reliability and Validity of the Sexual Experiences Survey–Short Forms Victimization and Perpetration. Violence Vict. 2017, 32, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/ugexcerpts.shtml (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Hald, G.M.; Malamuth, N.M. Self-Perceived Effects of Pornography Consumption. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2007, 37, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokunaga, R.S.; Wright, P.J.; Vangeel, L. Is Pornography Consumption a Risk Factor for Condomless Sex? Hum. Commun. Res. 2020, 46, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, I.; Krahé, B. Predicting Sexual Victimization Among College Students in Chile and Turkey: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2565–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, I.; Krahé, B. Predictors of Sexual Aggression Perpetration Among Male and Female College Students: Cross-Cultural Evidence from Chile and Turkey. Sex. Abus. A J. Res. Treat. 2018, 31, 318–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canan, S.N.; Jozkowski, K.N.; Crawford, B.L. Sexual Assault Supportive Attitudes: Rape Myth Acceptance and Token Resistance in Greek and Non-Greek College Students from Two University Samples in the United States. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 33, 3502–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.P.; Kingree, J.B.; Zinzow, H.; Swartout, K. Time-Varying Risk Factors and Sexual Aggression Perpetration Among Male College Students. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Busby, D.M.; Willoughby, B.J.; Chiu, H.-Y.; Olsen, J.A. Measuring the Multidimensional Construct of Pornography: A Long and Short Version of the Pornography Usage Measure. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 3027–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohut, T.; Balzarini, R.; Fisher, W.A.; Grubbs, J.B.; Campbell, L.; Prause, N. Surveying Pornography Use: A Shaky Science Resting on Poor Measurement Foundations. J. Sex Res. 2019, 57, 722–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dawson, K.; Nic Gabhainn, S.; MacNeela, P. Toward a Model of Porn Literacy: Core Concepts, Rationales, and Approaches. J. Sex Res. 2020, 57, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, E.F.; Adhia, A.; Christensen, T.T.; Paruk, J.; Alder, J.; Daley, N. A Pornography Literacy Class for Youth: Results of a Feasibility and Efficacy Pilot Study. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 2018, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, I.; Bernards, J.; Bean, R.A.; Young, B.; Wolfgramm, M. Addressing Problematic Pornography Use in Adolescent/Young Adult Males: A Literature Review and Recommendations for Family Therapists. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2021, 49, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable (Range) | Total Sample M (SD) | Men M (SD) | Women M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pornography realism + (1–25) | 5.45 (3.43) | 7.59 (3.68) a | 4.26 (2.61) b |

| Risky sexual scripts ++ (1–25) | 7.11 (3.01) | 7.43 (3.11) a | 6.94 (2.95) b |

| Risky sexual behavior (1–5) | 2.04 (0.60) | 2.02 (0.62) | 2.05 (0.59) |

| Acceptance of sexual coercion (1–5) | 1.42 (0.58) | 1.42 (0.60) | 1.42 (0.57) |

| Sexual victimization (0–4) | 1.16 (1.41) | 0.76 (1.22) a | 1.38 (1.46) b |

| Sexual aggression victimization (% yes) | 53.4 | 37.7 a | 62.1 b |

| Sexual aggression perpetration (% yes) | 12.3 | 17.7 a | 9.4 b |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pornography realism | - | 0.29 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.22 *** |

| 2. Risky sexual scripts | 0.15 *** | - | 0.59 *** | 0.25 *** |

| 3. Risky sexual behavior | 0.10 * | 0.67 *** | - | 0.17 ** |

| 4. Acceptance of sexual coercion | 0.15 *** | 0.02 | 0.01 | - |

| Indirect Paths | ß | 99% C.I. |

|---|---|---|

| Pornography realism -> Risky script -> Risky behavior -> Victimization | 0.050 | 0.020; 0.076 |

| Pornography realism -> Risky script -> Risky behavior -> Perpetration | 0.038 | 0.019; 0.067 |

| Pornography realism -> Acceptance of sexual coercion -> Victimization | 0.022 | 0.005; 0.046 |

| Pornography realism -> Acceptance of sexual coercion -> Perpetration | 0.033 | 0.010; 0.066 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krahé, B.; Tomaszewska, P.; Schuster, I. Links of Perceived Pornography Realism with Sexual Aggression via Sexual Scripts, Sexual Behavior, and Acceptance of Sexual Coercion: A Study with German University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010063

Krahé B, Tomaszewska P, Schuster I. Links of Perceived Pornography Realism with Sexual Aggression via Sexual Scripts, Sexual Behavior, and Acceptance of Sexual Coercion: A Study with German University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrahé, Barbara, Paulina Tomaszewska, and Isabell Schuster. 2022. "Links of Perceived Pornography Realism with Sexual Aggression via Sexual Scripts, Sexual Behavior, and Acceptance of Sexual Coercion: A Study with German University Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010063

APA StyleKrahé, B., Tomaszewska, P., & Schuster, I. (2022). Links of Perceived Pornography Realism with Sexual Aggression via Sexual Scripts, Sexual Behavior, and Acceptance of Sexual Coercion: A Study with German University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010063